“Avoidance” Is Not “Escape”: The Impact of Avoidant Job Crafting on Work Disengagement

Abstract

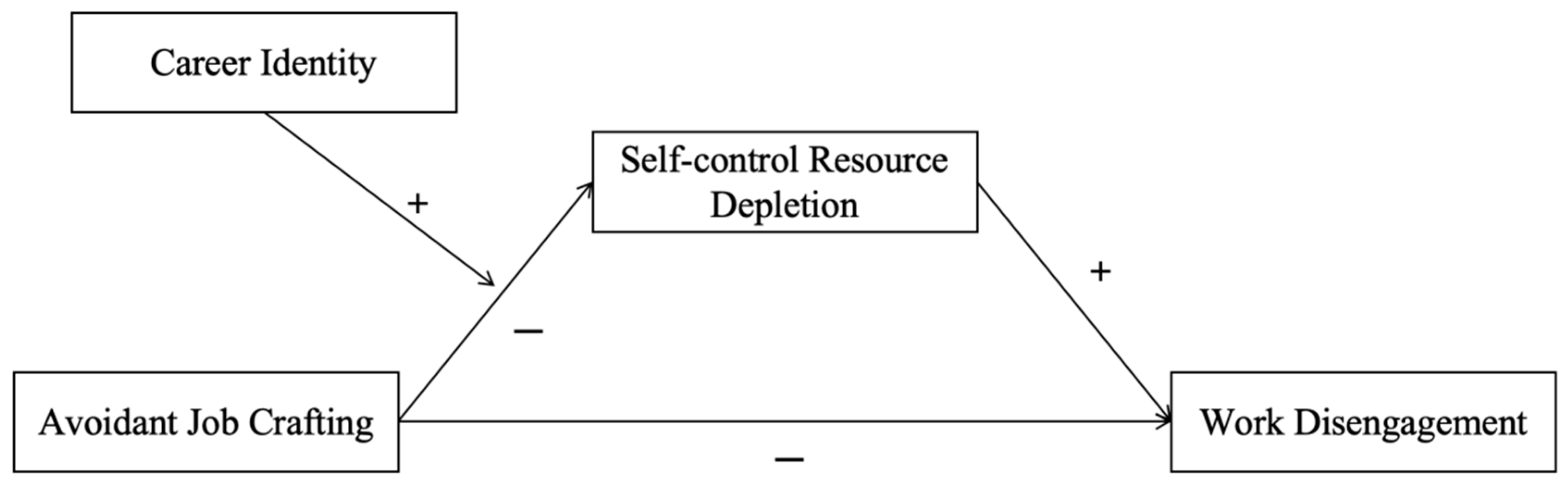

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Avoidant Job Crafting and Work Disengagement

2.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Control Resource Depletion

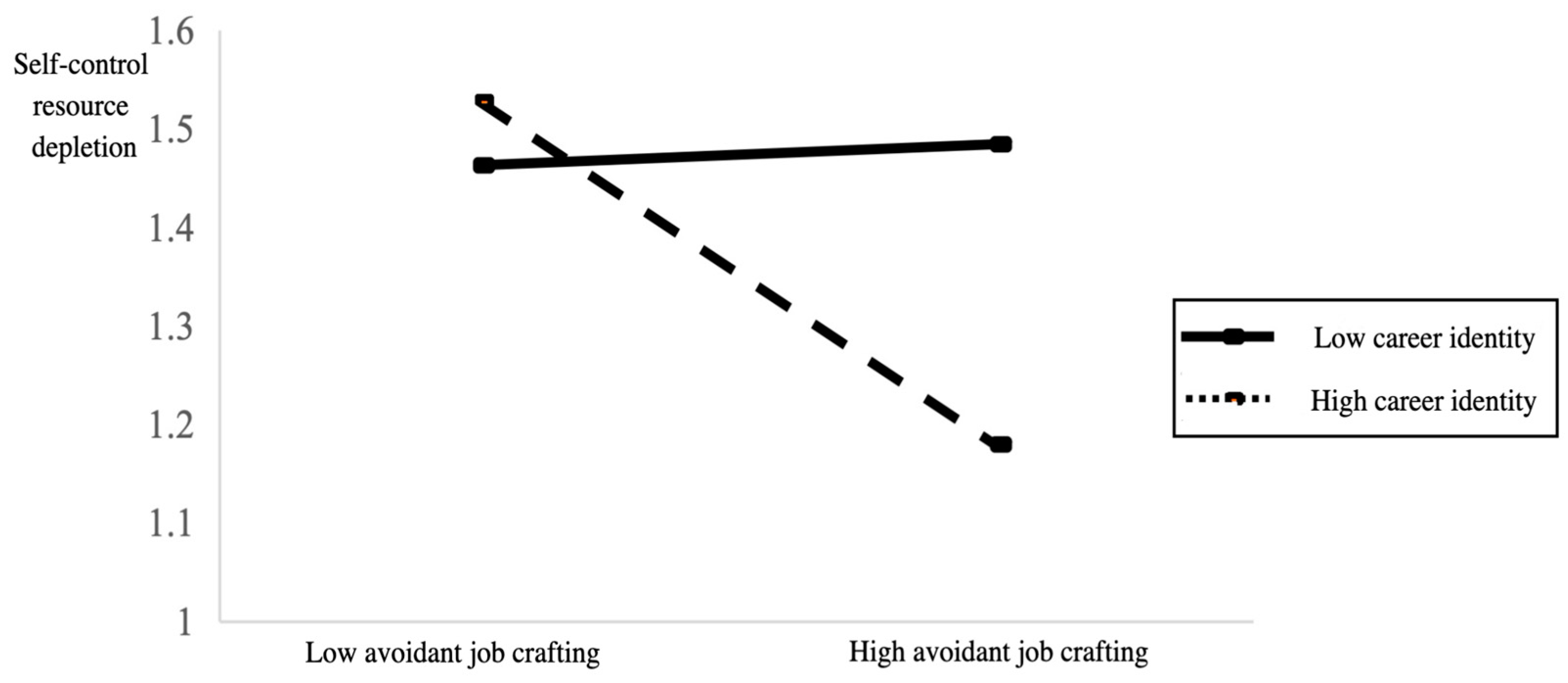

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Career Identity

3. Study

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance Test

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Variables

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadi, H. A., Coetzer, A., Roxas, H., & Pishdar, M. (2022). Informal learning and career identity formation: The mediating role of work engagement. Personnel Review, 52(1), 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrahi, B., Blenkinsopp, J., De Arroyabe, J. C. F., & Karim, M. S. (2021). Work disengagement: A review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 32(2), 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M. U., Bajwa, S. U., Shahzad, K., & Aslam, H. (2020). Psychological contract violation and turnover intention: The role of job dissatisfaction and work disengagement. Employee Relations, 42(6), 1291–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P., & Conley, S. (1991). Work-home conflict among nurses and engineers: Mediating the impact of role stress on burnout and satisfaction at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & De Vries, J. D. (2020). Job demands–resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 34(5), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Vergel, A. I. S. (2015). Modelling job crafting behaviours: Implications for work engagement. Human Relations, 69(1), 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R., & Snyder, R. (1972). Ego identity and motivation: An empirical study of achievement and affiliation in Erikson’ s theory. Psychological Reports, 30(3), 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A. A., Bakker, A. B., & Field, J. G. (2017). Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T., & Demerouti, E. (2015). Which employees craft their jobs and how? Basic dimensions of personality and employees’ job crafting behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(4), 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnlein, P., & Baum, M. (2020). Does job crafting always lead to employee well-being and performance? Meta-analytical evidence on the moderating role of societal culture. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(4), 647–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, V., & Bernecker, K. (2021). Persistence and disengagement in personal goal pursuit. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruning, P. F., & Campion, M. A. (2017). A role–resource approach–avoidance model of Job crafting: A multimethod integration and extension of job crafting theory. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P. A., Hood, M., & Hu, S. (2017). Personal orientation as an antecedent to career stress and employability confidence: The intervening roles of career goal-performance discrepancy and career goal importance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P. A., Kaya, M., & Hood, M. (2018). Vocational identity and career progress: The intervening variables of career calling and willingness to compromise. Journal of Career Development, 47(2), 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M. (2025). A comparative study of job insecurity: Who suffers more? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37, 1603–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. (2014). Design your own job through job crafting. European Psychologist, 19(4), 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. (2015). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H., Coyle-Shapiro, J., & Yang, Q. (2017). Beyond reciprocity: A conservation of resources view on the effects of psychological contract violation on third parties. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(5), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C. Y. M., Tims, M., Khapova, S. N., & Beijer, S. (2020). Supervisor Reactions to Avoidance Job Crafting: The role of political skill and approach job crafting. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1209–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. (2021, August 12). State of the global workplace: 2022 Report [EB/OL]. Available online: https://news.800hr.com/1628732680/200047/1/0.html (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Harju, L. K., Kaltiainen, J., & Hakanen, J. J. (2021). The double-edged sword of job crafting: The effects of job crafting on changes in job demands and employee well-being. Human Resource Management, 60(6), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. (2012). Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Freedy, J. (2017). Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In Professional burnout (pp. 115–129). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2017). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B., Stein, A. M., Mao, Y., & Yan, A. (2021). The influence of human resource management systems on employee job crafting: An integrated content and process approach. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(1), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Im, J., & Qu, H. (2018). Exploring antecedents and consequences of job crafting. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotabe, H. P., & Hofmann, W. (2015). On integrating the components of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & De Gennaro, D. (2019). The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H., Yam, K. C., & Ferris, D. L. (2015). Self-control at work. Academy of Management Annals, 123(6), 1227–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2018). A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., & Johnson, R. E. (2015). A suggestion to improve a day keeps your depletion away: Examining promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors within a regulatory focus and ego depletion framework. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., Liu, S., Wu, H., Wu, K., & Pei, J. (2022). To avoidance or approach: Unraveling hospitality employees’ job crafting behavior response to daily customer mistreatment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 53, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Ganegoda, D. B., Chen, Z. X., Jiang, X., & Dong, C. (2020). Effects of perceived overqualification on career distress and career planning: Mediating role of career identity and moderating role of leader humility. Human Resource Management, 59(6), 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(13), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makikangas, A. (2018). Job crafting profiles and work engagement: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoulli, M. P., Lee, C. I. S. G., Byington, E., & Felps, W. A. (2017). Mapping human resource management: Reviewing the field and charting future directions. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, H., Karakowsky, L., & Podolsky, M. (2021). Exploring job crafting as a response to abusive supervision. Career Development International, 26(2), 174–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F., & Lengelle, R. (2012). Narratives at work: The development of career identity. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(2), 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L., Zhang, W., Wang, X., & Liang, S. (2018). Moderating effects of time pressure on the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention in social E-commerce sales promotion: Considering the impact of product involvement. Information & Management, 56(2), 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, P., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2021). Interactive Effects of approach and avoidance Job crafting in explaining weekly variations in work performance and employability. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundt, A., & Venz, L. (2017). Personal need for structure as a boundary condition for humor in leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(1), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A., Pati, S. R., Krishnan, T. N., & Krishnan, S. (2018). Causes, contingencies, and consequences of disengagement at work: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 17(1), 62–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., Li, Y., Xie, Y., Huang, Z., Cheng, A., Zhou, X., Li, J., Qin, R., Wei, X., Liu, Y., Xia, X., Song, Q., Zhao, L., Liu, Z., Xiao, D., & Wang, C. (2024). Acute and long COVID-19 symptoms and associated factors in the omicron-dominant period: A nationwide survey via the online platform Wenjuanxing in China. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B., Zhu, F., Lin, S., Sun, J., Wu, Y., & Xiao, W. (2022). How is professional identity associated with teacher career satisfaction? A cross-sectional design to test the multiple mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2015). Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, R., & Holmes, O. (2014). Abusive supervision and feedback avoidance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Tims, M., & Parker, S. K. (2025). Combinations of approach and avoidance crafting matter: Linking job crafting profiles with proactive personality, autonomy, work engagement, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 46, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extracted Loading Squares | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance Percentage | Cumulative Percentage % | Total | Variance Percentage | Cumulative Percentage % | |

| 1 | 10.30 | 41.19 | 41.19 | 10.30 | 41.19 | 41.19 |

| 2 | 2.73 | 10.91 | 52.10 | 2.73 | 10.91 | 52.10 |

| 3 | 2.28 | 9.12 | 61.22 | 2.28 | 9.12 | 61.22 |

| 4 | 2.15 | 8.59 | 69.81 | 2.15 | 8.59 | 69.81 |

| 5 | 0.69 | 2.75 | 72.55 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Avoidance job crafting | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.89 | |||

| 2. Self-control resource depletion | −0.32 *** | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.92 | ||

| 3. Work disengagement | −0.29 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.92 | |

| 4. Career identity | 0.40 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.25 *** | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.93 |

| Items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Avoidant job crafting (Tims et al., 2012) | 3.49 | 0.90 |

| 1. I make sure that my work is mentally less intense | 3.34 | 1.15 |

| 2. I try to ensure that my work is emotionally less intense | 3.44 | 1.03 |

| 3. I manage my work so that I try to minimize contact with people whose problems affect me emotionally | 3.49 | 1.11 |

| 4. I organize my work so as to minimize contact with people whose expectations are unrealistic | 3.11 | 1.13 |

| 5. I try to ensure that I do not have to make many difficult decisions at work | 3.71 | 1.05 |

| 6. I organize my work in such a way to make sure that I do not have to concentrate for too long a period at once | 3.83 | 1.14 |

| Self-control resource depletion (Lin & Johnson, 2015) | 2.42 | 0.97 |

| 1. I feel drained | 2.23 | 0.96 |

| 2. My mind feels unfocused right now | 2.70 | 1.16 |

| 3. Right now, it would take a lot of effort for me to concentrate on something | 2.33 | 1.07 |

| 4. My mental energy is running low | 2.48 | 1.28 |

| 5. I feel like my willpower is gone | 2.37 | 1.13 |

| Work disengagement (Pundt & Venz, 2017) | 2.46 | 0.83 |

| 1. I can always find something new and fun in my work (reversed) | 2.44 | 0.88 |

| 2. I usually talk about my work in a derogatory way | 2.85 | 1.07 |

| 3. Lately, I’ve been thinking very little about my work, just getting things done mechanically | 2.34 | 1.18 |

| 4. I find my work challenging (reversed) | 2.56 | 1.18 |

| 5. If this continues, I may gradually distance myself from my job | 2.38 | 0.92 |

| 6. Sometimes, my work assignments make me feel uncomfortable | 2.89 | 1.02 |

| 7. The type of work I do fits my identity (reversed) | 2.13 | 1.07 |

| 8. I get more and more engaged in my work (reversed) | 2.09 | 0.96 |

| Career identity (Mael & Ashforth, 1992) | 3.58 | 0.94 |

| 1. When someone praises my career, it feels like a personal compliment | 3.94 | 0.91 |

| 2. I am very interested in what others think about my career | 3.42 | 0.96 |

| 3. When someone criticizes my career, it feels like a personal insult | 3.29 | 1.23 |

| 4. When I talk about my career, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’ | 3.61 | 1.25 |

| 5. My career’s successes are my successes | 3.65 | 0.99 |

| 6. If a story in the media criticized my career, I would feel embarrassed | 3.58 | 1.17 |

| Self-Control Resource Depletion | Work Disengagement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Gender | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Education | −0.12 *** | −0.16 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.140 ** |

| Tenure | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Position | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 |

| Job level | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Avoidant job crafting | −0.08 * | −0.36 *** | −0.34 *** | |

| Self-control resource depletion | 0.27 *** | 0.22 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.56 * | 0.31 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.34 *** |

| ΔR2 | 0.00 * | 0.10 *** | 0.03 *** | 0.02 *** |

| Career Identity | Moderated Indirect Effect | Moderated Mediation Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IND EFFECT | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| Higher level (M + 1SD) | 4.61 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.01 | −0.34 | −0.01 |

| Average level (Mean) | 3.67 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | ||||

| Lower level (M − 1SD) | 2.72 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Deng, W.; Deng, J. “Avoidance” Is Not “Escape”: The Impact of Avoidant Job Crafting on Work Disengagement. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050611

Yang T, Wang Y, Liu J, Wang T, Deng W, Deng J. “Avoidance” Is Not “Escape”: The Impact of Avoidant Job Crafting on Work Disengagement. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050611

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Tianan, Ying Wang, Jingyi Liu, Tianyu Wang, Wenhao Deng, and Jianwei Deng. 2025. "“Avoidance” Is Not “Escape”: The Impact of Avoidant Job Crafting on Work Disengagement" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050611

APA StyleYang, T., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Wang, T., Deng, W., & Deng, J. (2025). “Avoidance” Is Not “Escape”: The Impact of Avoidant Job Crafting on Work Disengagement. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050611