The Role of Students’ Perceptions of Educators’ Communication Accommodative Behaviors in Classrooms in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Backdrop

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Instructions

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Demographic Characteristics Difference in the Study Variables

4.3. Data Analysis

4.3.1. Measurement Model

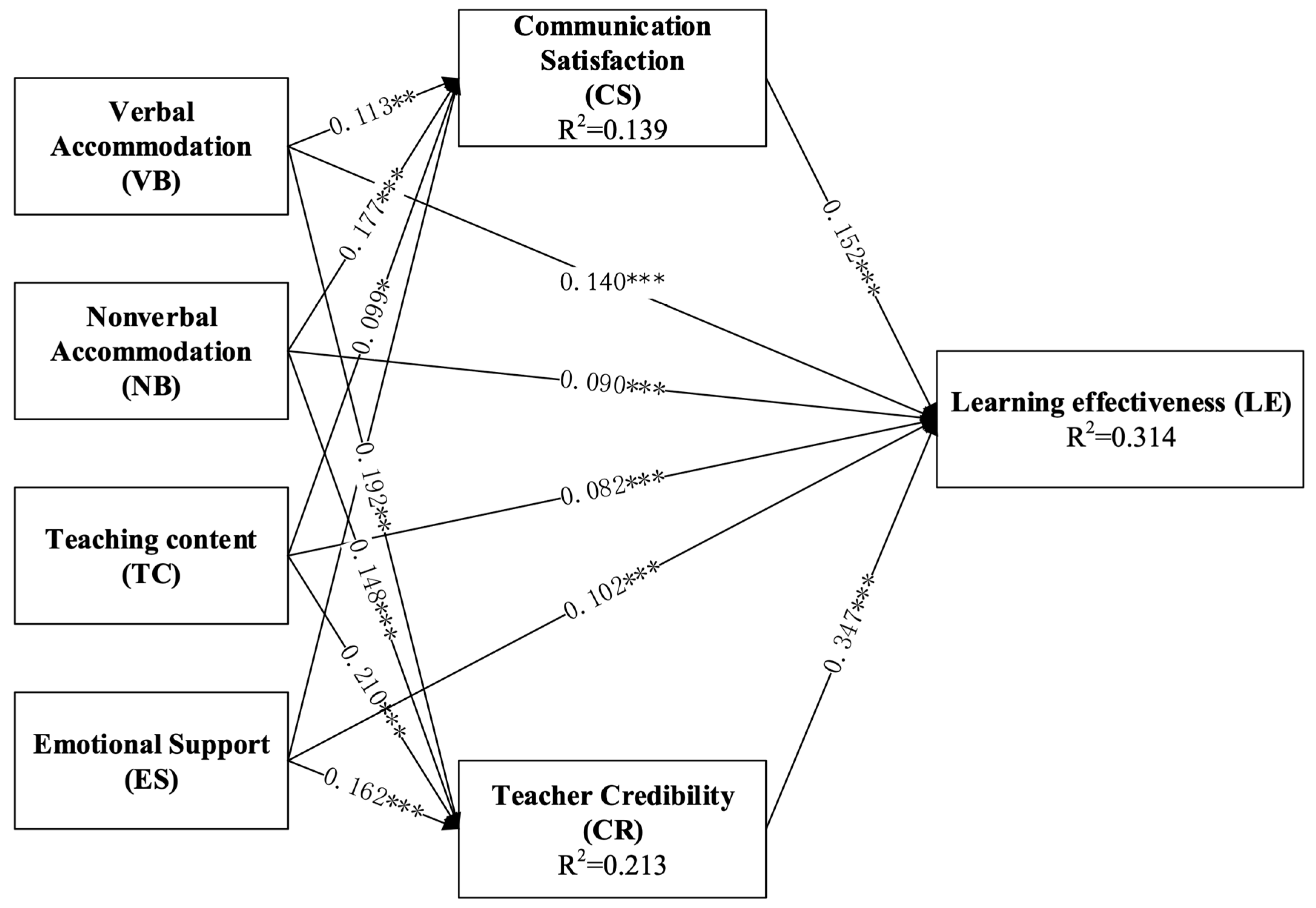

4.3.2. Structural Model

Direct Effect

Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allard, A., & Holmstrom, A. J. (2023). Students’ perception of an instructor: The effects of instructor accommodation to student swearing. Language Sciences, 99, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atma, B. A., Azahra, F. F., Mustadi, A., & Adina, C. A. (2021). Teaching style, learning motivation, and learning achievement: Do they have significant and positive relationships? Jurnal Prima Edukasia, 9(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banas, J. A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S. J. (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braskamp, L. A., Brandenburg, D. C., Kohen, E., Ory, J. C., & Mayberry, P. W. (1984). Guidebook for evaluating teaching. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brok, P., Bergen, T., Stahl, R. J., & Brekelmans, M. (2004). Students’ perceptions of teacher control behaviors. Learning and Instruction, 14(4), 425–443. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/99377/. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. H. (2019). Exploring teacher-student communication in senior-education contexts in Taiwan: A communication accommodation approach. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 13(1), 63–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C., Khajavy, H., Raddawi, R., & Giles, H. (2019). Perceptions of police-civilian encounters: Intergroup and communication dimensions in the United Arab Emirates and the USA. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 12(1), 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, J., Coupland, N., Giles, H., & Henwood, K. (1988). Accommodating the elderly: Invoking and extending a theory. Language in Society, 17(1), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W. J., Xia, W., & Torkzadeh, G. (1994). A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 18(4), 453–461. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/249524 (accessed on 18 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Donovan, H., & Forster, E. (2015). Communication adaption in challenging simulations for student nurse midwives. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(10), 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhami, A. (2020). Communication accommodation theory: A brief review of the literature. Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy, 4(5), 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackler, S., Malmberg, L. E., & Sammons, P. (2021). An international perspective on teacher self-efficacy: Personal, structural and environmental factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A. N., Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., Elledge, N., Jernberg, K. A., & Larson, L. M. (2009). A meta-analytical review of teacher credibility and its associations with teacher behaviors and student outcomes. Communication Education, 58(4), 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, T. K., & Lane, D. R. (2021). CAT in the classroom: A multilevel analysis of students’ experiences with instructor nonaccommodation. Communication Education, 70(3), 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, C., Weatherall, A., & Giles, H. (2016). CAT and talk in action. In H. Giles (Ed.), Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts (pp. 105–122). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H. (2016). Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H., Edwards, A. L., & Walther, J. B. (2023). Communication accommodation theory: Past accomplishments, current trends, and future prospects. Language Sciences, 99, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, H., Markowitz, D., & Clementson, D. (Eds.). (in press-a). CAT-aloguing the past, present and future of accommodation theory and research. In New directions for, and panaceas arising from, communication accommodation theory. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H., Markowitz, D., & Clementson, D. (Eds.). (in press-b). New directions for, and panaceas arising from, communication accommodation theory. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Goodboy, A. K., Martuin, M., & Bolkan, S. (2009). The development and validation of the Student Communication Satisfaction Scale. Communication Education, 58(3), 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017a). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (Pls-Sem) using R. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017b). Pls-Sem or Cb-Sem: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of Pls-Sem. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M. L. (1978). Conceptualization and measurement of interpersonal communication satisfaction. Human Communication Research, 4(3), 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Christian, M. R., & Marko, S. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildt, E. (2021). What sort of robots do we want to interact with? Reflecting on the human side of human-artificial intelligence interaction. Frontiers in Computer Science, 3, 671012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, M. L., & Hosek, A. M. (2018). Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. I. (2013). Student in-class texting behavior: Associations with instructor clarity and classroom relationships. Communication Research Reports, 30, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, E. H., & Garcia, F. E. (2019). Measuring learning effectiveness: A new look at no-significant-difference findings. Online Learning, 4(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E., & Hecht, M. L. (2004). Elaborating the communication theory of identity: Identity gaps and communication outcomes. Communication Quarterly, 52(3), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L. S. (2006). Building a communication foundation in adult education: Partnering adult learning theory with communication accommodation theory in andragogical settings. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. [Google Scholar]

- Manju, G. (2015). Effectiveness of communication accommodation theory (CAT) in teaching of English as a second language in India. GNOSIS, 1(3), 224–234. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288128454_Effectiveness_of_Communication_Accommodation_Theory_CAT_in_Teaching_of_English_as_a_Second_Language_in_India (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Manuaba, I. B., & Putra, I. N. A. J. (2021). The types of communication accommodation strategies in English as foreign language (EFL) classrooms. Journal of Education Research and Evaluation, 5(1), 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazer, J. P., & Hunt, S. K. (2008). “Cool” communication in the classroom: A preliminary examination of student perceptions of instructor use of positive slang. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 9(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazer, J. P., & Stowe, S. A. (2015). Can teacher immediacy reduce the impact of verbal aggressiveness? Examining effects on student outcomes and perceptions of teacher credibility. Western Journal of Communication, 80(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., & Bennett, V. E. (2006). The relationships of student end-of-class motivation with teacher communication behaviors and instructional outcomes. Communication Education, 55(4), 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (1999). Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Communications Monographs, 66(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. A., & Goodboy, A. (2014). College student learning, motivation, and satisfaction as a function of effective instructor communication behaviors. Southern Communication Journal, 79(1), 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nabila, A. R., Munir, A., & Anam, S. (2020). Teacher’s motives in applying communication accommodation strategies in secondary ELT class. Linguistic, English Education and Art (LEEA) Journal, 3(2), 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayernia, A., Taghizadeh, M., & Farsani, M. A. (2020). EFL teachers’ credibility, nonverbal immediacy, and perceived success: A structural equation modeling approach. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1774099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negovan, V., Raciu, A., & Vlad, M. (2010). Gender and school-related experience differences in students’ perception of teacher interpersonal behavior in the classroom. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., & Hamid, M. O. (2019). Language choice, identity and social distance: Ethnic minority students in Vietnam. Applied Linguistics Review, 10(2), 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishghadam, R., Derakhshan, A., Jajarmi, H., Tabatabaee Farani, S., & Shayesteh, S. (2021). Examining the role of teachers’ stroking behaviors in EFL learners’ active/passive motivation and teacher success. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 707314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, M. J., & Harwood, J. (2015). Communication accommodation competence: The nature and nurture of accommodative resources across the lifespan. Language and Communication, 41, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S. (2017). Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instruments development. International Journal of Economics & Management Sciences, 6(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabnejad, F., Pishghadam, R., & Saboori, F. (2017). On the influence of stroke on willingness to attend classes and foreign language achievement. Applied Research on English Language, 6(2), 141–158. Available online: https://profdoc.um.ac.ir/paper-abstract-1062806.html (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in Hrm research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, B. A., Hedberg, P. R., & Gower, K. (2016). Enhancing teacher credibility: What we can learn from the justice and leadership literature. Organization Management Journal, 13(2), 90–100. Available online: https://scholarship.shu.edu/omj/vol13/iss2/5 (accessed on 18 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P. (2013). Content relevance and students’ comfort with disclosure as moderators of instructor disclosures and credibility in the college classroom. Communication Education, 62(4), 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollitto, M., Johnson, Z. D., & Myers, S. A. (2013). Students’ Perceptions of College Classroom Connectedness, Assimilation, and Peer Relationships. Communication Education, 62(3), 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, R. B., Giles, H., & Denes, A. (2013). Investigating stepparent-stepchild interactions: The role of communication accommodation. Journal of Family Communication, 13(3), 218–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C. O. (2022). STEM identities: A communication theory of identity approach. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 41(2), 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, K. (2003). Learning effectiveness online: What the research tells us. In Elements of quality online education, practice and direction. Sloan Center for Online Education. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/43/files/2009/09/learning-effectiveness.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Tsai, Y.-R., & Tsou, W. (2015). Accommodation strategies employed by non-native English-mediated instruction (EMI) teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(2), 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, L., Gasiorek, J., & Dragojevic, M. (2017). Little chance for divergence: The role of interlocutor language constraint in online bilingual accommodation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 27(3), 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, B. C., Hecht, M. L., & Jung, E. (2008). The role of identity gaps, discrimination, and acculturation in international students’ educational satisfaction in American classrooms. Communication Education, 57(1), 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, B. M., Jones, L., & Hewett, D. G. (2016). Accommodating health. In H. Giles (Ed.), Communication Accommodation Theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts (pp. 152–168). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. (2021). A functional review of research on clarity, immediacy, and credibility of teachers and their impacts on motivation and engagement of students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 712419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W. (2019). Teacher-student interaction in EFL classroom in China: Communication accommodation theory perspective. English Language Teaching, 12(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Item | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 213 | 50.5 |

| female | 209 | 49.5 | |

| Age | 18–23 | 260 | 61.6 |

| 24–29 | 134 | 31.8 | |

| 30–35 | 14 | 3.3 | |

| 36–40 | 9 | 2.1 | |

| ≥41 | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Education level | Freshman | 68 | 16.1 |

| Sophomore | 55 | 13 | |

| Junior | 68 | 16.1 | |

| Senior | 55 | 13 | |

| Graduate student | 34 | 8.1 | |

| Postgraduate student | 79 | 18.7 | |

| Nation | China | 320 | 75.8 |

| Australia | 1 | 0.2 | |

| French | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Japan | 20 | 4.7 | |

| Korea | 34 | 8.1 | |

| UK | 27 | 6.4 | |

| Canada | 1 | 0.2 | |

| America | 9 | 2.1 | |

| Thailand | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Ukraine | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Other | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Malaya | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Number of responses | 422 | 100% |

| Items | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Student Perception of Teacher Accommodation Communication Behavior (PACB) | ||

| Nonverbal behavior (NB) | 1. Made eye contact with me 2. Smiled at me 3. Showed enthusiasm 4. Used gestures to emphasize points 5. Moved around the classroom when speaking | Frey & Lane (2021) and Speer et al. (2013) |

| Verbal behavior (VB) | 1. Concentrated on articulating words for clarity 2. Tried to use simple language 3. Made an effort to pronounce words correctly 4. Used slang that I would use | |

| Teaching content (TC) | 1. Provided feedback to me 2. Incorporated examples to make course content relevant 3. Explained course content thoroughly 4. Repeated his/her ideas to help me understand | |

| Emotional support (ES) | 1. Provided emotional support 2. Made me feel comfortable 3. Was concerned about my success in the class 4. Was responsive to my needs 5. Empathized with me | |

| Students’ communication satisfaction (CS) | ||

| 1. My communication with my teacher feels satisfying. 2. My teacher fulfills my expectations when I talk to him/her. 3. My conversations with my teacher are worthwhile. 4. My teacher genuinely listens to me when I talk. 5. My teacher tends to dominate our conversations and not allow me to get my point across. | Goodboy et al. (2009) and Hecht (1978) | |

| Teacher’s credibility (CR) | ||

| Competence | 1. I think he/she is competent to teach this course. 2. I think the teacher has received professional training and is highly professional. 3. I think he/she is full of wisdom. 4. I think he/she lacks professional knowledge. | McCroskey and Teven (1999) |

| Goodwill | 1. I think he/she is concerned about students. 2. I think he/she attached importance to students’ interest in learning. 3. I think he/she is self-centered. 4. I think he/she can understand students. | |

| Trustworthiness | 1. I think he/she is honest and trustworthy. 2. I think he/she is trustworthy. 3. I think he/she is honest. 4. I think he/she abides by ethics. | |

| Learning effectiveness (LE) | ||

| 1. Instructor’s teaching methods are flexible and diverse and can adapt to individual differences. 2. The instructor explained this clearly in class. 3. The instructor can give timely feedback on students’ questions. 4. The instructor was open to students’ views. | Braskamp et al. (1984) | |

| Nationality | N | Mean | Standard Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonverbal behavior | Chinese | 320 | 4.79 | 1.82 | 0.018 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.15 | 1.81 | |||

| Verbal behavior | Chinese | 320 | 4.07 | 2.01 | 0.455 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.21 | 1.94 | |||

| Teaching content | Chinese | 320 | 4.11 | 1.54 | 0.00 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.15 | 1.67 | |||

| Emotional support | Chinese | 320 | 4.47 | 1.81 | −0.134 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.22 | 1.99 | |||

| Communication satisfaction | Chinese | 320 | 4.63 | 1.29 | 1.646 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.33 | 1.37 | |||

| Teacher’s credibility | Chinese | 320 | 4.72 | 1.31 | 1.813 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.43 | 1.27 | |||

| Learning effectiveness | Chinese | 320 | 4.43 | 1.37 | 1.180 | >0.05 |

| non-Chinese | 102 | 4.17 | 1.43 |

| Gender | N | Mean | Standard Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonverbal behavior | F | 209 | 4.34 | 1.72 | 1.74 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.12 | 1.90 | |||

| Verbal behavior | F | 209 | 4.01 | 2.02 | −0.86 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.08 | 1.96 | |||

| Teaching content | F | 209 | 4.06 | 1.63 | −0.65 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.15 | 1.52 | |||

| Emotional support | F | 209 | 4.05 | 1.87 | −0.16 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.38 | 1.84 | |||

| Communication satisfaction | F | 209 | 4.50 | 1.33 | −1.04 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.63 | 1.28 | |||

| Teacher’s credibility | F | 209 | 4.59 | 1.31 | −1.02 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.72 | 1.30 | |||

| Learning effectiveness | F | 209 | 4.38 | 1.42 | 0.05 | >0.05 |

| M | 213 | 4.38 | 1.36 |

| Age | N | Mean | SD | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication satisfaction | 18–23 | 260 | 4.62 | 1.30 | 0.70 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.53 | 1.34 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.07 | 0.99 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.36 | 1.45 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 4.64 | 0.92 | |||

| Teacher’s credibility | 18–23 | 260 | 4.65 | 1.34 | 0.98 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.75 | 1.25 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.21 | 1.09 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.10 | 1.29 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 4.63 | 1.42 | |||

| Learning effectiveness | 18–23 | 260 | 4.42 | 1.39 | 1.32 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.34 | 1.41 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.89 | 1.28 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.08 | 1.24 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 5.41 | 1.02 | |||

| Nonverbal behavior | 18–23 | 260 | 4.78 | 1.87 | 0.43 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.89 | 1.70 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.50 | 1.54 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.53 | 2.26 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 4.08 | 2.46 | |||

| Teaching content | 18–23 | 260 | 4.01 | 1.59 | 0.84 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.29 | 1.52 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.91 | 1.48 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.14 | 2.18 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 4.55 | 0.69 | |||

| Emotional support | 18–23 | 260 | 4.70 | 1.90 | 0.35 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 4.91 | 1.79 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.74 | 1.51 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.49 | 2.40 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 5.08 | 0.97 | |||

| Verbal behavior | 18–23 | 260 | 4.05 | 2.04 | 1.24 | >0.05 |

| 24–30 | 134 | 5.79 | 1.96 | |||

| 31–35 | 14 | 4.88 | 0.78 | |||

| 36–40 | 9 | 4.52 | 2.38 | |||

| >41 | 5 | 4.20 | 1.07 |

| Grades | N | Mean | SD | F | p | Post Hoc Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication satisfaction | Freshman | 68 | 4.16 | 1.36 | 2.62 | <0.05 | 6 < 1 < 2 1 < 4 1 < 5 |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.91 | 1.26 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.46 | 1.31 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.68 | 1.30 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.66 | 1.24 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.40 | 1.36 | ||||

| Teacher’s credibility | Freshman | 68 | 4.47 | 1.25 | 1.45 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.59 | 1.48 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.38 | 1.26 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.66 | 1.35 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.88 | 1.25 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.59 | 1.26 | ||||

| Learning effectiveness | Freshman | 68 | 4.24 | 1.35 | 0.46 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.43 | 1.39 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.21 | 1.28 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.34 | 1.43 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.50 | 1.42 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.37 | 1.39 | ||||

| Nonverbal behavior | Freshman | 68 | 4.79 | 1.86 | 2.05 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.06 | 1.79 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.95 | 2.29 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.78 | 1.85 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.96 | 1.69 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.60 | 1.62 | ||||

| Teaching content | Freshman | 68 | 4.91 | 1.70 | 1.36 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.81 | 1.44 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.82 | 1.67 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 5.18 | 1.64 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 5.27 | 1.50 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 5.13 | 1.54 | ||||

| Emotional support | Freshman | 68 | 5.74 | 2.01 | 0.31 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 5.64 | 1.68 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.67 | 1.92 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.65 | 2.09 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.84 | 1.76 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.98 | 1.68 | ||||

| Verbal behavior | Freshman | 68 | 4.35 | 1.67 | 0.74 | >0.05 | |

| Sophomore | 55 | 4.90 | 2.20 | ||||

| Junior | 34 | 4.67 | 2.40 | ||||

| Senior | 79 | 4.83 | 2.24 | ||||

| Graduate student | 135 | 4.60 | 1.83 | ||||

| Postgraduate student | 51 | 4.98 | 1.87 |

| Items | Factor Loading | AVE (>0.5) | Composite Reliability (>0.6) | Cronbach’s Alpha (>0.7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonverbal behavior (NB) | NB1 | 0.894 | 0.802 | 0.953 | 0.939 |

| NB2 | 0.901 | ||||

| NB3 | 0.913 | ||||

| NB4 | 0.910 | ||||

| NB5 | 0.857 | ||||

| Verbal behavior (VB) | VB1 | 0.930 | 0.876 | 0.955 | 0.930 |

| VB2 | 0.936 | ||||

| VB3 | 0.943 | ||||

| Teaching content (TC) | TC1 | 0.887 | 0.791 | 0.938 | 0.912 |

| TC2 | 0.909 | ||||

| TC3 | 0.887 | ||||

| Emotional support (ES) | ES1 | 0.907 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.945 |

| ES2 | 0.917 | ||||

| ES3 | 0.899 | ||||

| ES4 | 0.891 | ||||

| Communication satisfaction (CS) | CS1 | 0.873 | 0.648 | 0.900 | 0.858 |

| CS2 | 0.853 | ||||

| CS3 | 0.850 | ||||

| CS4 | 0.854 | ||||

| CS5 | 0.545 | ||||

| Teacher’s credibility (CR) | CR1 | 0.843 | 0.628 | 0.952 | 0.943 |

| CR2 | 0.825 | ||||

| CR3 | 0.861 | ||||

| CR4 | 0.513 | ||||

| CR5 | 0.844 | ||||

| CR6 | 0.820 | ||||

| CR7 | 0.518 | ||||

| CR8 | 0.805 | ||||

| CR9 | 0.848 | ||||

| CR10 | 0.836 | ||||

| CR11 | 0.851 | ||||

| CR12 | 0.839 | ||||

| Learning effectiveness (LE) | LE1 | 0.858 | 0.743 | 0.920 | 0.885 |

| LE2 | 0.872 | ||||

| LE3 | 0.864 | ||||

| LE4 | 0.853 |

| ES | LE | CS | CR | TC | NB | VB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | |||||||

| LE | 0.320 | ||||||

| CS | 0.291 | 0.439 | |||||

| CR | 0.290 | 0.572 | 0.445 | ||||

| TC | 0.320 | 0.336 | 0.230 | 0.349 | |||

| NB | 0.210 | 0.304 | 0.280 | 0.270 | 0.205 | ||

| VB | 0.104 | 0.344 | 0.201 | 0.306 | 0.206 | 0.202 |

| Path Hypotheses | Sample Mean | Std | t-Value | p-Value | F-Square | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VB -> CR | 0.207 | 0.045 | 4.598 | 0 | 0.051 | Supported |

| VB -> CS | 0.113 | 0.046 | 2.452 | 0.014 | 0.006 | Supported |

| VB -> LE | 0.230 | 0.026 | 4.391 | 0 | 0.028 | Supported |

| NB -> CR | 0.148 | 0.045 | 3.276 | 0.001 | 0.026 | Supported |

| NB -> CS | 0.177 | 0.047 | 3.813 | 0 | 0.033 | Supported |

| NB -> LE | 0.168 | 0.025 | 4.117 | 0 | 0.031 | Supported |

| ES -> CR | 0.162 | 0.047 | 3.432 | 0.001 | 0.030 | Supported |

| ES -> CS | 0.192 | 0.046 | 4.209 | 0 | 0.038 | Supported |

| ES -> LE | 0.187 | 0.024 | 4.73 | 0 | 0.011 | Supported |

| TC -> CR | 0.210 | 0.044 | 4.813 | 0 | 0.049 | Supported |

| TC -> CS | 0.099 | 0.048 | 2.085 | 0.037 | 0.021 | Supported |

| TC -> LE | 0.170 | 0.025 | 4.497 | 0 | 0.020 | Supported |

| CR -> LE | 0.347 | 0.043 | 10.334 | 0 | 0.137 | Supported |

| CS -> LE | 0.152 | 0.047 | 4.412 | 0 | 0.029 | Supported |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | t Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | VAF % | Mediation Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VB -> CR -> LE | 0.056 | 0.072 | 0.019 | 3.77 | 0 | 44.72 | Yes |

| VB -> CS -> LE | 0.029 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 1.877 | 0.061 | 16.03 | No |

| NB -> CR -> LE | 0.051 | 0.053 | 0.018 | 2.905 | 0.004 | 65.57 | Yes |

| NB -> CS -> LE | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.012 | 2.3 | 0.022 | 25.71 | Yes |

| ES -> CR -> LE | 0.073 | 0.057 | 0.018 | 3.107 | 0.002 | 39.43 | Yes |

| ES -> CS -> LE | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.012 | 2.53 | 0.011 | 25.22 | Yes |

| TC -> CR -> LE | 0.072 | 0.074 | 0.019 | 3.896 | 0 | 45.34 | Yes |

| TC -> CS -> LE | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 1.751 | 0.08 | 14.56 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, D.; Giles, H.; Hu, W. The Role of Students’ Perceptions of Educators’ Communication Accommodative Behaviors in Classrooms in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040560

Ji D, Giles H, Hu W. The Role of Students’ Perceptions of Educators’ Communication Accommodative Behaviors in Classrooms in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040560

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Dan, Howard Giles, and Wei Hu. 2025. "The Role of Students’ Perceptions of Educators’ Communication Accommodative Behaviors in Classrooms in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040560

APA StyleJi, D., Giles, H., & Hu, W. (2025). The Role of Students’ Perceptions of Educators’ Communication Accommodative Behaviors in Classrooms in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040560