The Impact of Resource Inequality on Cooperative Behavior in Social Dilemmas

Abstract

1. Introduction

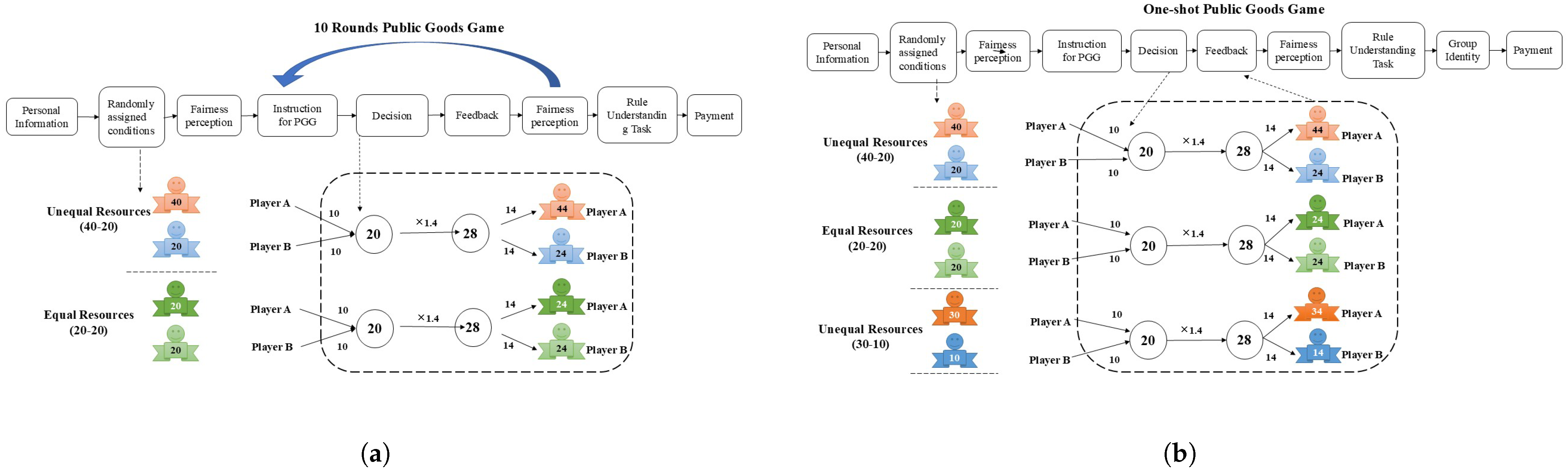

2. Experiment 1: Effects of Resource Inequality on Cooperation in Social Dilemmas

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Design

2.1.3. Materials

A Two-Player Public Goods Game

Rule Understanding Task

Fairness Perception

Debriefing Questions

2.1.4. Procedure

2.2. Results

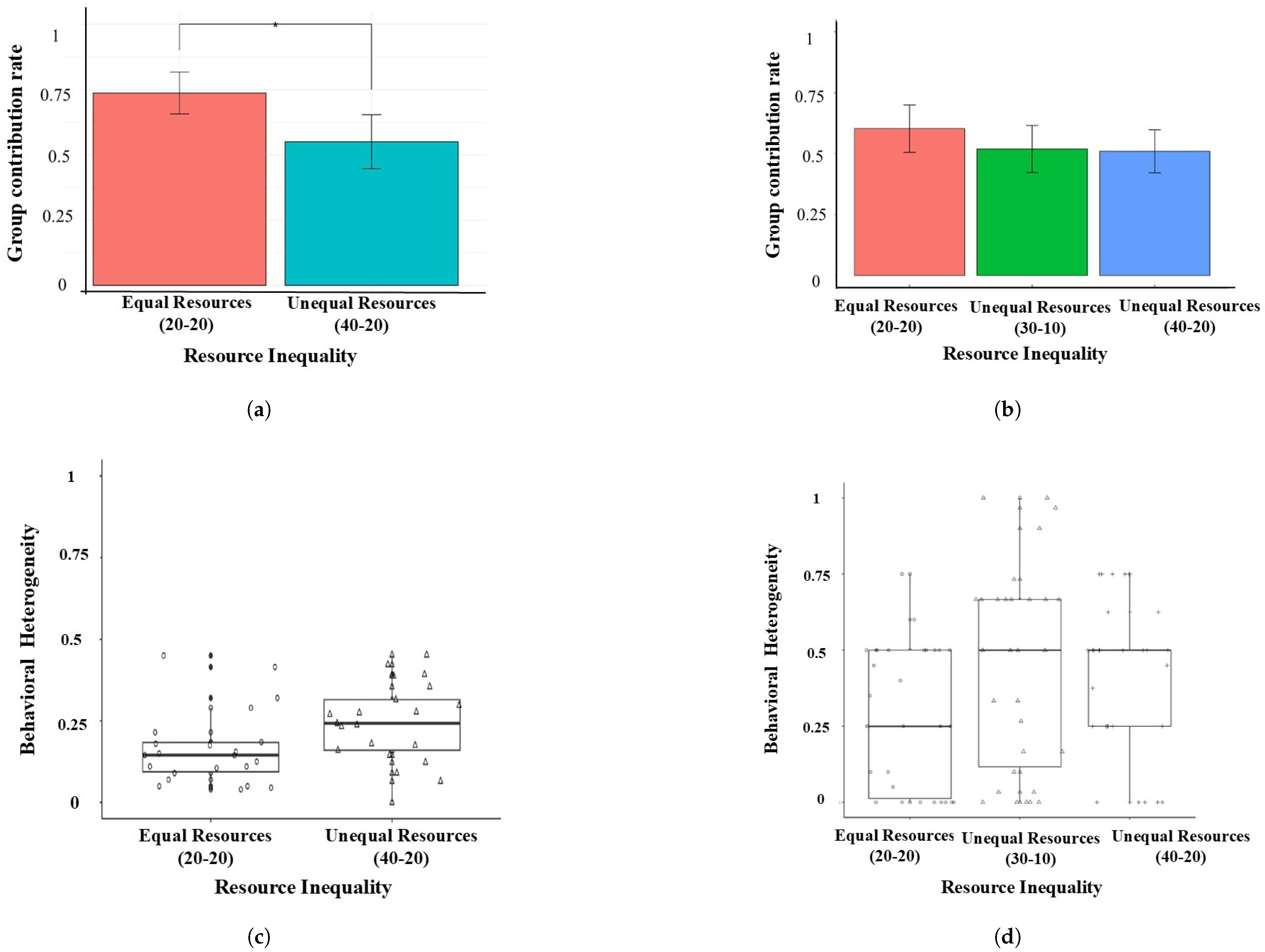

2.2.1. Group Cooperation Level Under Unequal Resources and Equal Resources Conditions

2.2.2. Cooperation Among Players Under Unequal Resources Condition

2.2.3. Mediating Effect: Fairness Perception

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Design

3.1.3. Materials

Public Goods Game

Rule Understanding Task

Fairness Perception Tasks

Group Identity Measures

3.1.4. Procedure

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Group Cooperation Level Under Unequal and Equal Resources Conditions

3.2.2. Cooperation Among Players Under Unequal Resources Conditions

3.2.3. Mediating Effect: Fairness Perception and Group Identity

4. General Discussion

4.1. Effects of Resource Inequality on Group Cooperation

4.2. Cooperation for Different Resource Players

4.3. Mediating Effect: Fairness Perception and Group Identity

4.4. Limitations and Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aksoy, O. (2019). Crosscutting circles in a social dilemma: Effects of social identity and inequality on cooperation. Social Science Research, 82, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. R., Mellor, J. M., & Milyo, J. (2008). Inequality and public good provision: An experimental analysis. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K., Steisel, V., & Kay, A. (2016). The effects of resource distribution, voice, and decision framing on the provision of public goods. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 36(4), 665–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, T. L., Kroll, S., & Shogren, J. F. (2005). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: Evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 57(3), 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A., & Zipay, K. P. (2015). Justice, fairness, and employee reactions. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutchman, P., Amir, D., Jordan, M. R., & McAuliffe, K. (2022). Common knowledge promotes cooperation in the threshold public goods game by reducing uncertainty. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(2), 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, J. M. Y., & Au, W.-t. (2014). Effect of inequality on cooperation: Heterogeneity and hegemony in public goods dilemma. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabka, M. M., & Goebel, J. (2018). Income distribution in Germany: Real income on the rise since 1991 but more people with low incomes. DIW Weekly Report, 8(21), 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves Heap, S. P., Ramalingam, A., & Stoddard, B. V. (2016). Endowment inequality in public goods games: A re-examination. Economics Letters, 146, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, E., & Piff, P. (2018). When inequality is good for groups: The moderating role of fairness. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, O. P., Hilbe, C., Chatterjee, K., & Nowak, M. A. (2019). Social dilemmas among unequals. Nature, 572(7770), 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. A. (2003). Handbook of Self and Identity (M. R. Leary, & J. P. Tangney, Eds.). Chap. Social identity. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasso, G., Törnblom, K. Y., & Sabbagh, C. (2016). Distributive justice [Book Section]. In C. Sabbagh, & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 201–218). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Joel, H. S. (2023). Higher income individuals are more generous when local economic inequality is high. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0286273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E. J., Häubl, G., & Keinan, A. (2007). Aspects of endowment: A query theory of value construction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33(3), 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, H., Decety, J., & Lee, K. (2013). Experiencing a natural disaster alters children’s altruistic giving. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C., & Hao, F. (2015). Decision making in asymmetric social dilemmas: A dual mode of action. Advances in Psychological Science [Chinese], 23(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.-Y., Xin, Z., Zhang, H., Du, X., Zheng, Y., & Zhong, Z. (2025a). Watching eyes effect on prosocial behaviours: Evidence from experimental games with real interaction. Current Psychology, 44, 1920–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.-Y., Zhang, H., Yu, Y., Xue, Z., Cai, Y., & Luo, Z. (2025b). Praise and cooperation: Investigating the effects of praise content and agency. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 115, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nockur, L., Pfattheicher, S., & Keller, J. (2021). Different punishment systems in a public goods game with asymmetric endowments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 93, 104096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M., Lv, J.-Y., & Proulx, M. J. (2018). Can empathy promote cooperation when status and money matter? Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 40(4), 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Cote, S., Cheng, B. H., & Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, A., & Stoddard, V. B. (2024). Does reducing inequality increase cooperation? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 217, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A., & Suleiman, R. (1993). Incremental contribution in step-level public goods games with asymmetric players. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 55(2), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrieh, A., & Verbon, H. A. A. (2006). Inequality, cooperation, and growth: An experimental study. European Economic Review, 50(5), 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(4), 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E., & Wilke, H. (1995). Coordination rules in asymmetric social dilemmas: A comparison between public good dilemmas and resource dilemmas. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lange, P. A. M., Joireman, J., Parks, C. D., & Van Dijk, E. (2013). The psychology of social dilemmas: A review. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(2), 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. M., Kopelman, S., & Messick, D. M. (2004). A conceptual review of decision making in social dilemmas: Applying a logic of appropriateness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(3), 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. (2007). The multiplicity of taxpayer identities and their implications for tax ethics. Law & Policy, 29(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. (2017). Social justice, institutional trust and public cooperation intention. Acta Psychologica Sinica [Chinese], 49(06), 794–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Cheng, L., Li, Z., Xiao, L., & Wang, F. (2022). Economic inequality perception dampens meritocratic belief in china: The mediating role of perceived distributive unfairness. International Review of Social Psychology, 35(1), 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Absolute Contribution : High Endowment | Absolute Contribution : Low Endowment | Contribution Rate : High Endowment | Contribution Rate : Low Endowment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unequal Resources 40-20 condition in E1 | 20.03 (9.57) | 12.98 (4.69) | 0.50 (0.24) | 0.65 (0.70) |

| Unequal Resources 30-10 condition in E2 | 14.03 (9.97) | 6.73 (3.76) | 0.47 (0.33) | 0.67 (0.38) |

| Unequal Resources 40-20 condition in E2 | 18.17 (11.96) | 12.41 (0.34) | 0.45 (0.30) | 0.62 (0.34) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, J.; Wang, H.; Cai, W.; Yang, D.; Yu, Y. The Impact of Resource Inequality on Cooperative Behavior in Social Dilemmas. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040519

Lv J, Wang H, Cai W, Yang D, Yu Y. The Impact of Resource Inequality on Cooperative Behavior in Social Dilemmas. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040519

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Jieyu, Huan Wang, Wei Cai, Danli Yang, and Yonghong Yu. 2025. "The Impact of Resource Inequality on Cooperative Behavior in Social Dilemmas" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040519

APA StyleLv, J., Wang, H., Cai, W., Yang, D., & Yu, Y. (2025). The Impact of Resource Inequality on Cooperative Behavior in Social Dilemmas. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040519