The Effect of Exercise Atmosphere on College Students’ Physical Exercise—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Exercise Atmosphere and Physical Exercise

1.2. The Mediating Role of Enjoyment

1.3. The Mediating Role of Exercise Self-Efficacy

1.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Enjoyment and Exercise Self-Efficacy

1.5. The Moderating Role of Social Physique Anxiety

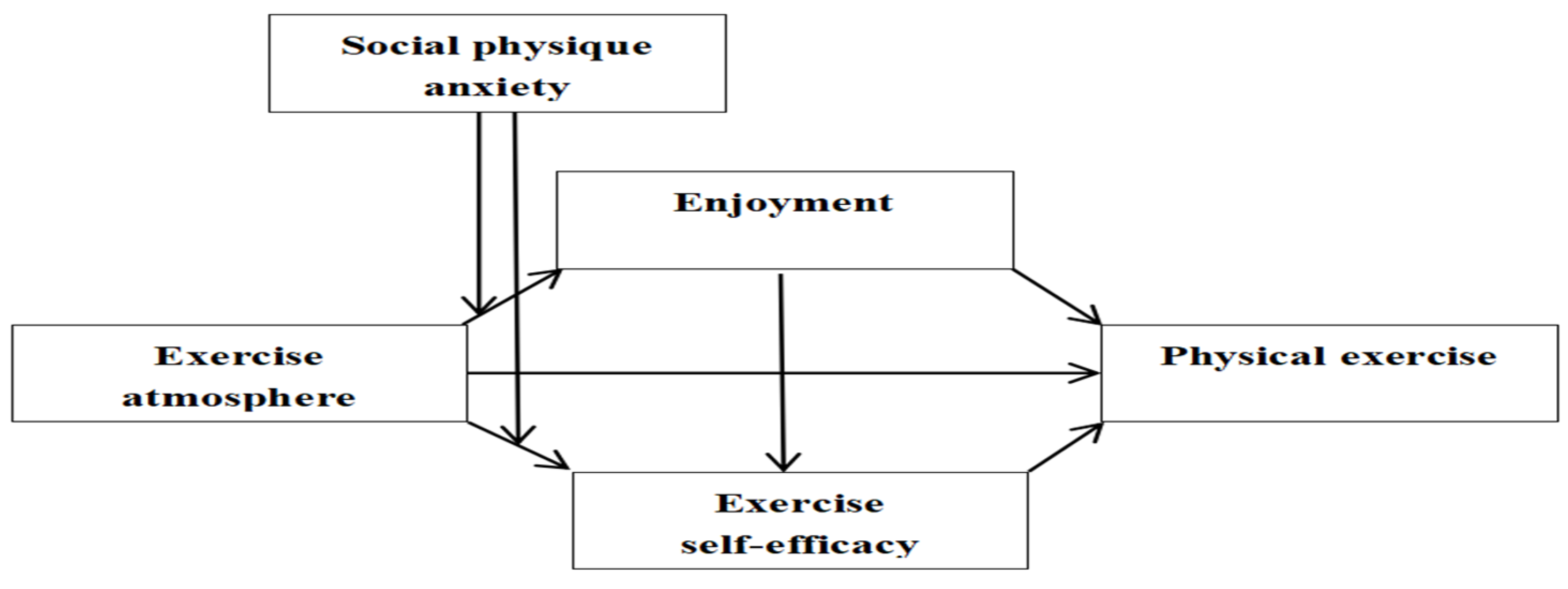

1.6. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Physique Anxiety Scale

2.2.2. Enjoyment Scale

2.2.3. Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale

2.2.4. Exercise Atmosphere Scale

2.2.5. Physical Exercise Rating Scale

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Exercise Atmosphere on Physical Exercise

4.2. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Enjoyment

4.3. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Exercise Self-Efficacy

4.4. Analysis of the Chain Mediating Role of Enjoyment and Exercise Self-Efficacy

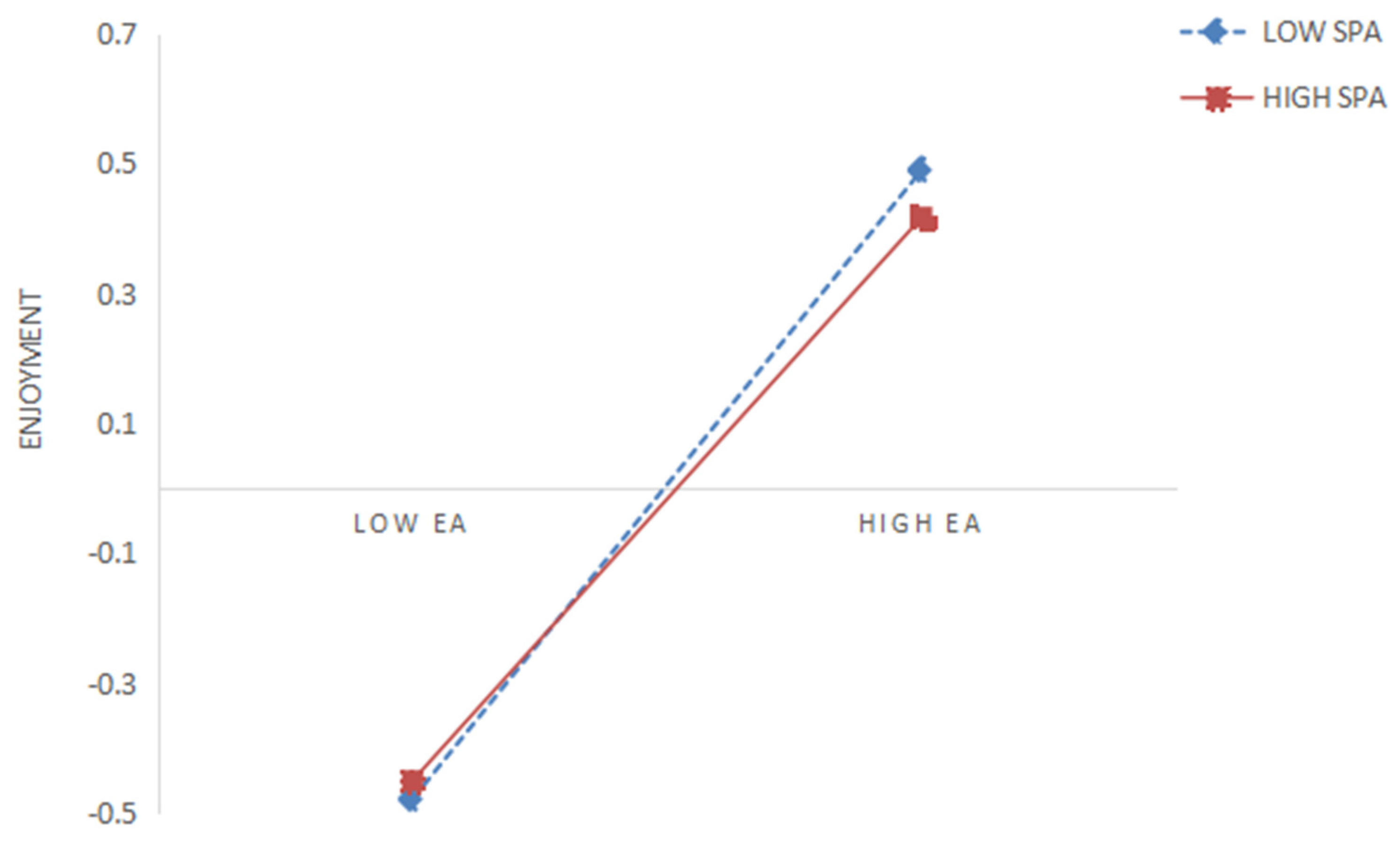

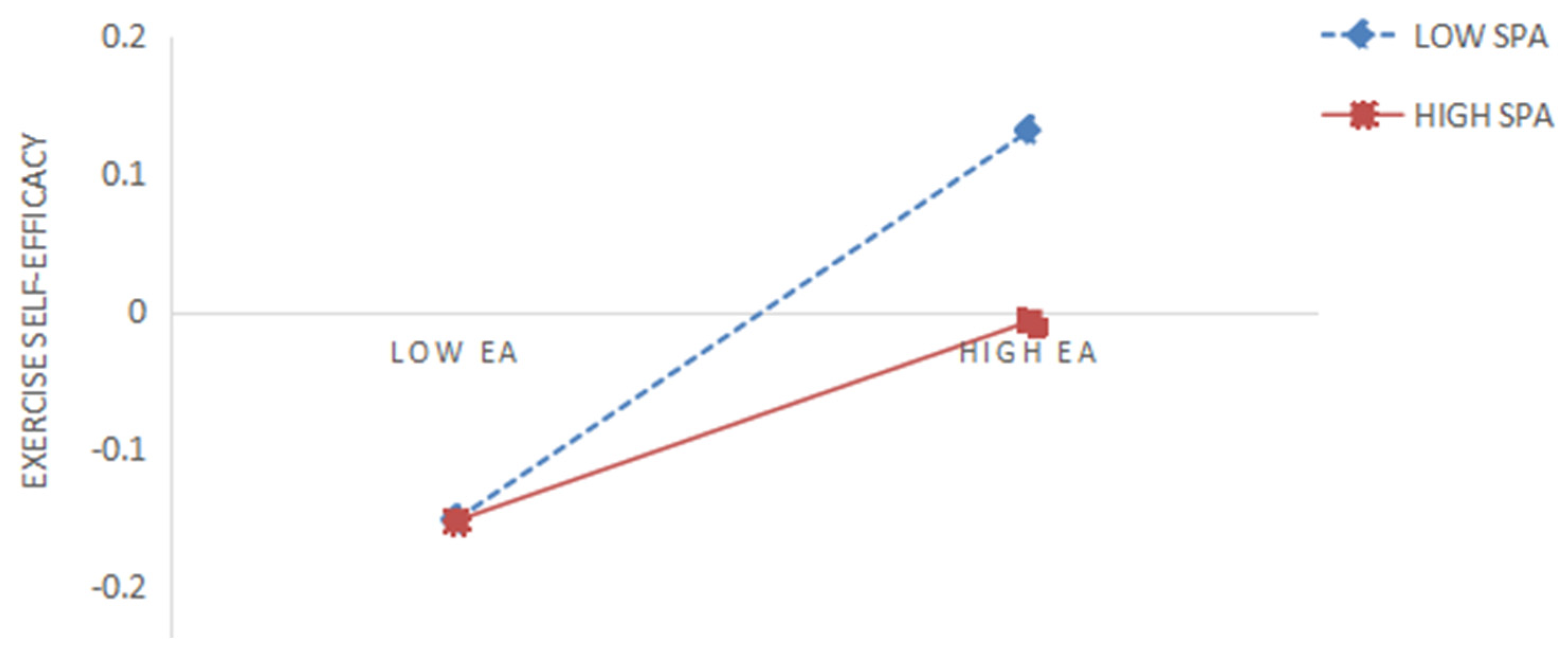

4.5. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Social Physique Anxiety

5. Implications

6. Limitations and Prospects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajibewa, T. A., Sonneville, K. R., Miller, A. L., Toledo-Corral, C. M., Robinson, L. E., & Hasson, R. E. (2024). Weight stigma and physical activity avoidance among college-aged students. Journal of American College Health, 72(8), 2323–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anić, P., Pokrajac-Bulian, A., & Mohorić, T. (2022). Role of sociocultural pressures and internalization of appearance ideals in the motivation for exercise. Psychological Reports, 125(3), 1628–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, F. (2013). The effect of exercise on affective and self-efficacy responses in older and younger women. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 10(1), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, R., & Ekkekakis, P. (2018). Affective–Reflective theory of physical inactivity and exercise. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 48(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. R. (2000). Does social physique anxiety affect women’s motivation to exercise (pp. 219–224). Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanac, M., & Bonniot-Cabanac, M. C. (2007). Decision making: Rational or hedonic? Behavioral and Brain Functions, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. J., Liu, Y., & Liu, Y. (2012). The Design of theoretical frame of sports geography under a microscope study. Journal of Shanghai University of Sport, 36(3), 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Sun, H., & Dai, J. (2017). Peer support and adolescents’ physical activity: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and enjoyment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(5), 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. P., & Li, S. C. (2007). The mechanism of physical exercise behavior persistence: Exploration, measurement tools and empirical research. Xi ‘an Jiao tong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. F., & Dong, B. L. (2018). Influence of exercise atmosphere and subjective experience on leisure physical exercise of undergraduates. Journal of TUS, 33(2), 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X. Y., Wang, Z. J., & Xiao, H. Y. (2020). Dual system theory of physical activity: A reinforcement learning perspective. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(8), 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S., & Eklund, R. C. (1994). Social physique anxiety, reasons for exercise, and attitudes toward exercise settings. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, R. K., Motl, R. W., Saunders, R., Felton, G., Ward, D. S., Dowda, M., & Pate, R. R. (2005). Enjoyment mediates effects of a school-based physical-activity intervention. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 37(3), 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B. L., & Mao, L. J. (2018). Core beliefs, deliberate rumination and exercise adherence of undergraduate: The moderated mediating effect of exercise atmosphere. Journal of TUS, 33(5), 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B. L., Zhang, H., Zhu, L. Q., & Cheng, Y. F. (2018). Influence of health beliefs, self-efficacy and social support on leisure exercise for adolescents. Journal of Shandong Sport University, 34(5), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. Q., Ge, Y. Y., Ding, F., Zhong, J. W., & Li, X. C. (2022). Influence of cumulative ecological risk on college students physical exercise: The mediating effect of exercise atmosphere and exercise self-efficacy. China Journal of Health Psychology, 30(8), 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. Q., Wu, J. T., Wang, C. S., Ge, Y. Y., Wu, Y. Z., Zhang, C. Y., & Hu, J. (2023). Cross lag study on adolescents exercise atmosphere, psychological resilience and mobile phone dependence. China Journal of Health Psychology, 31(2), 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, D., Abrams, K., Adolphs, R., Ahmed, M. E., Beatty, A., Berridge, K. C., Broomhall, S., Brosch, T., Campos, J. J., Clay, Z., Clément, F., Cunningham, W. A., Damasio, A., Damasio, H., D’Arms, J., Davidson, J. W., de Gelder, B., Deonna, J., de Sousa, R., … Sander, D. (2021). The rise of affectivism. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(7), 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. Y., Fan, X. H., & Liu, Y. (2008). Perceived discrimination and loneliness: Moderating effects of coping style among migrant children. Psychological Development and Education, (4), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Harney, M. B., Brownstone, L. M., Higgins, M. K., & Bardone-Cone, A. M. (2012). Examining social physique anxiety and disordered eating in college women. The roles of social comparison and body surveillance. Appetite, 59(3), 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, C. M., & Morrison, C. S. (1996). Social physique anxiety: Personality constructs, motivations, exercise attitudes, and behaviors. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82(3), 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A. C., & Simonton, K. L. (2022). Motivation beliefs, emotions, leisure time physical activity, and sedentary behavior in university students: A full longitudinal model of mediation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 58, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Shao, W. Z., Zheng, L., & Shang, G. R. (2023). The double-edged sword effects of weight self-stigma on adolescents’ exercise behavior: An empirical analysis based on the social information processing theory. China Sport Science, 43(11), 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, E. A., Leary, M. R., & Rejeski, W. J. (1989). Tie measurement of social physique anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Methodology in the social sciences. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M. R. (1992). Self-presentational processes in exercise and sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(4), 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. A., Williams, D. M., Frayeh, A., & Marcus, B. H. (2016). Self-efficacy versus perceived enjoyment as predictors of physical activity behaviour. Psychology & Health, 31(4), 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. W., & Wang, X. C. (2018). A behavioral study of the impact of emotion valence on movement speed. Journal of Shanghai University of Sport, 42(2), 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Xu, J., Zhang, X., & Chen, G. (2024). The relationship between exercise commitment and college students’ exercise adherence: The chained mediating role of exercise atmosphere and exercise self-efficacy. Acta Psychologica, 246, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D. Q. (1994). The stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 8(1), 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. H., Wang, L. J., Yan, P., & Zhang, X. Q. (2017). The realistic problems and development countermeasures of “sunshine Sports” in Chinese universities. Sports Culture Guide, (9), 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. N., Zhou, C. L., & Sun, J. (2011). Effect of outdoor sport motivation on sport adherence in adolescents-The mediating mechanism of sport atmosphere. China Sport Science, 31(10), 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E., Jerome, G. J., Elavsky, S., Marquez, D. X., & Ramsey, S. N. (2003). Predicting long-term maintenance of physical activity in older adults. Preventive Medicine, 37(2), 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MeAuley, E., & Courneya, K. S. (1994). The subjective exercise experiences scale (SEES): Development and preliminary validation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(2), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G., Wikman, J. M., Jensen, C. J., Schmidt, J. F., Gliemann, L., & Andersen, T. R. (2014). Health promotion: The impact of beliefs of health benefits, social relations and enjoyment on exercise continuation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutter, S., Russell-Mayhew, S., & Saunders, J. F. (2021). Towards a sociocultural model of weight stigma. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X. G., Chen, S. P., & Zhang, Z. J. (2010). Research on physical exercise behaviors and effected factors of the undergraduates of sports community. Journal of Xi′an Physical Education University, 27(3), 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R. L., Wadden, T. A., & Jakicic, J. M. (2021). Is weight stigma associated with physical activity? A systematic review. Obesity, 29(12), 1994–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2005). Achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). User’s manual [Unpublished Manuscript]. University of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R. E., & Kates, A. (2015). Can the affective response to exercise predict future motives and physical activity behavior? A systematic review of published evidence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(5), 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. E., McEwan, D., & Rebar, A. L. (2019). Theories of physical activity behaviour change: A history and synthesis of approaches. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberger, S. M. (2014). An examination of social physique anxiety among college students: A mixed methodological approach. Georgia Southern University. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1050 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Rothberger, S. M., Harris, B. S., Czech, D. R., & Melton, B. (2015). The relationship of gender and self-efficacy on social physique anxiety among college students. International Journal of Exercise Science, 8(3), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabiston, C. M., Pila, E., Pinsonnault-Bilodeau, G., & Cox, A. E. (2014). Social physique anxiety experiences in physical activity: A comprehensive synthesis of research studies focused on measurement, theory, and predictors and outcomes. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., Zhang, Z., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Impact of exercise atmosphere on adolescents’ exercise behavior: Chain mediating effect of exercise identity and exercise habit. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(7), 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D. S., Rodrigues, F., Cid, L., & Monteiro, D. (2022). Enjoyment as a predictor of exercise habit, intention to continue exercising, and exercise frequency: The intensity traits discrepancy moderation role. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 780059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, D. S., Rodrigues, F., Machado, S., Cid, L., & Monteiro, D. (2021). Did you enjoy it? The role of intensity-trait preference/tolerance in basic psychological needs and exercise enjoyment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timme, S., Brand, R., & Raboldt, M. (2023). Exercise or not? An empirical illustration of the role of behavioral alternatives in exercise motivation and resulting theoretical considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1049356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, R. J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). 12 intrinsic motivation in sport. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 15(1), 389–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Gao, S., Chen, B., Liu, C., Wu, Z., Zhou, Y., & Sun, Y. (2022). A study on the correlation between undergraduate students’ exercise motivation, exercise self-efficacy, and exercise behaviour under the COVID-19 epidemic environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 946896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Liu, Y. P., & Gu, C. Q. (2016). Influential mechanism of amateur sport group cohesiveness on individual’s exercise adherence: A regulatory two layer intermediary model. Journal of Wuhan Institute of Physical Education, 50(3), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. E., & Du, F. Q. (2010). Relations between subjective exercise experience and physical health of middle school students. Journal of TUS, 25(3), 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z. L., & Ye, B. J. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(5), 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. Y., Ronis, D. L., Pender, N., & Jwo, J. L. (2002). Development of questionnaires to measure physical activity cognitions among Taiwanese adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 35(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X. (2003). Social Physique anxiety in sport and exercise: Preliminary research and instrument development. East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S., Li, M. D., Li, S. B., & Zhang, S. Z. (2019). Relationship between transactional leadership behavior and college students’willingness to exercise: Chain—Type intermediary of exercise self-efficacy and physical education class satisfaction. Journal of Shenyang Sport University, 38(04), 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. J. (2013). Relationship between physical activity and general self-efficacy: The role of endurance. Journal of Nanjing Sport Institute, 27(5), 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Hasibagen, & Zhang, C. (2022). The influence of social support on the physical exercise behavior of college students: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1037518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H. L., Xu, C. X., & Tang, Q. S. (2010). Study on the relationship among “cognitive gap”, “emotion” and tourist’s “place attachment”-A case study of dujiangyan. Human Geography, 25(5), 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., & Qiu, Y. (2006). An overview of sports friendship quality of teenagers abroad. Journal of Physical Education, 13(4), 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender | 0.60 ± 0.49 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2.Grade | 0.38 ± 0.49 | 0.106 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3.RR | 0.47 ± 0.50 | −0.028 | −0.041 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4.PF | 3.14 ± 1.04 | 0.159 ** | 0.019 | −0.087 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 5.BMI | 20.84 ± 3.65 | −0.162 ** | −0.023 | 0.022 | −0.206 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 6.SES | −0.05 ± 2.98 | −0.108 ** | −0.068 * | 0.413 ** | −0.067 * | 0.033 | 1 | |||||

| 7.SPA | 41.49 ± 9.00 | 0.167 ** | 0.002 | −0.039 | −0.009 | 0.073 ** | −0.105 ** | 1 | ||||

| 8.EN | 12.52 ± 3.55 | −0.175 ** | −0.013 | −0.020 | 0.112 ** | 0.052 | 0.007 | −0.109 ** | 1 | |||

| 9.ES | 18.66 ± 5.40 | −0.235 ** | −0.009 | −0.035 | 0.123 ** | 0.015 | 0.058 * | −0.168 ** | 0.553 ** | 1 | ||

| 10.EA | 37.87 ± 6.91 | −0.021 | 0.045 | 0.021 | 0.092 ** | 0.020 | 0.037 | −0.103 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.390 ** | 1 | |

| 11.PS | 18.40 ± 17.00 | −0.270 ** | −0.015 | 0.019 | 0.132 ** | 0.049 | 0.081 ** | −0.140 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.222 ** | 1 |

| EN | ES | PS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Gender | −0.188 | 0.025 | −7.420 *** | −0.165 | 0.025 | −6.554 *** | −0.206 | 0.027 | −7.519 *** |

| PF | 0.112 | 0.026 | 4.405 *** | 0.081 | 0.025 | 3.258 ** | 0.129 | 0.027 | 4.803 *** |

| BMI | 0.034 | 0.029 | 1.160 | −0.020 | 0.029 | −0.694 | 0.035 | 0.031 | 1.144 |

| SES | −0.022 | 0.025 | −0.885 | 0.038 | 0.024 | 1.599 | 0.054 | 0.026 | 2.091 * |

| EA | 0.494 | 0.025 | 20.129 *** | 0.155 | 0.028 | 5.591 *** | 0.064 | 0.030 | 2.129 * |

| EN | 0.441 | 0.029 | 15.480 *** | 0.155 | 0.034 | 4.636 *** | |||

| ES | 0.146 | 0.031 | 4.665 *** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.305 | 0.356 | 0.203 | ||||||

| F | 102.081 *** | 106.997 *** | 42.173 *** | ||||||

| Effect Size | BootSE | Boot95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Total effect | 0.195 | 0.028 | 0.139 | 0.249 |

| Direct effect | 0.064 | 0.029 | 0.008 | 0.123 |

| Total mediating effect | 0.131 | 0.020 | 0.094 | 0.171 |

| Mediating effect1 | 0.076 | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.115 |

| Mediating effect2 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.039 |

| Mediating effect3 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.018 | 0.048 |

| EN | ES | PS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Gender | −0.181 | 0.026 | −7.050 *** | −0.150 | 0.025 | −5.956 *** | -0.206 | 0.027 | −7.519 *** |

| PF | 0.113 | 0.026 | 4.434 *** | 0.083 | 0.025 | 3.359 ** | 0.129 | 0.027 | 4.803 *** |

| BMI | 0.035 | 0.030 | 1.173 | −0.014 | 0.029 | −0.492 | 0.035 | 0.031 | 1.144 |

| SES | −0.024 | 0.025 | −0.957 | 0.032 | 0.024 | 1.358 | 0.054 | 0.026 | 2.091 * |

| EA | 0.484 | 0.025 | 19.503 *** | 0.142 | 0.028 | 5.130 *** | 0.064 | 0.030 | 2.129 * |

| EN | 0.431 | 0.028 | 15.220 *** | 0.155 | 0.034 | 4.636 *** | |||

| ES | 0.146 | 0.031 | 4.665 *** | ||||||

| SPA | −0.022 | 0.025 | −0.889 | −0.070 | 0.024 | −2.897 ** | |||

| EA × SPA | −0.051 | 0.022 | −2.342 * | −0.069 | 0.021 | −3.312 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.310 | 0.369 | 0.203 | ||||||

| F | 74.231 *** | 84.472 *** | 42.173 *** | ||||||

| Moderated Path | SPA | Effect Size | BootSE | Boot95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Path1: EA-EN-PS | High (M + 1SD) | 0.067 | 0.018 | 0.034 | 0.104 |

| Low (M − 1SD) | 0.083 | 0.022 | 0.042 | 0.127 | |

| Between-group difference | −0.016 | 0.009 | −0.035 | −0.001 | |

| Path2: EA-ES-PS | High (M + 1SD) | 0.011 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.025 |

| Low (M − 1SD) | 0.031 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.052 | |

| Between-group difference | −0.020 | 0.009 | −0.041 | −0.005 | |

| Path3: EA-EN-ES-PS | High (M + 1SD) | 0.027 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.043 |

| Low (M − 1SD) | 0.034 | 0.009 | 0.018 | 0.052 | |

| Between-group difference | −0.007 | 0.004 | −0.015 | −0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Li, B.; He, X.; Jia, P.; Ye, Z. The Effect of Exercise Atmosphere on College Students’ Physical Exercise—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040507

Zhang T, Li B, He X, Jia P, Ye Z. The Effect of Exercise Atmosphere on College Students’ Physical Exercise—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040507

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ting, Bowen Li, Xinqi He, Peng Jia, and Zicong Ye. 2025. "The Effect of Exercise Atmosphere on College Students’ Physical Exercise—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040507

APA StyleZhang, T., Li, B., He, X., Jia, P., & Ye, Z. (2025). The Effect of Exercise Atmosphere on College Students’ Physical Exercise—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040507