Thinking Outside the Nation: Cognitive Flexibility’s Role in National Identity Inclusiveness as a Marker of Majority Group Acculturation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. National and Mainstream Identities

3. National Identity Inclusiveness

4. Majority Group Acculturation

5. Psychological Barriers to National Identity Inclusiveness

6. Flexible Mind at the Core of Inclusive Views

7. The Present Study

8. Method

8.1. Participants and Procedure

8.2. Materials

8.2.1. Cultural Identification Strength

8.2.2. Canadian Identity Inclusion

8.2.3. Majority Acculturation Orientations

8.2.4. Cognitive Flexibility

8.3. Analysis

9. Results

9.1. Descriptive Results

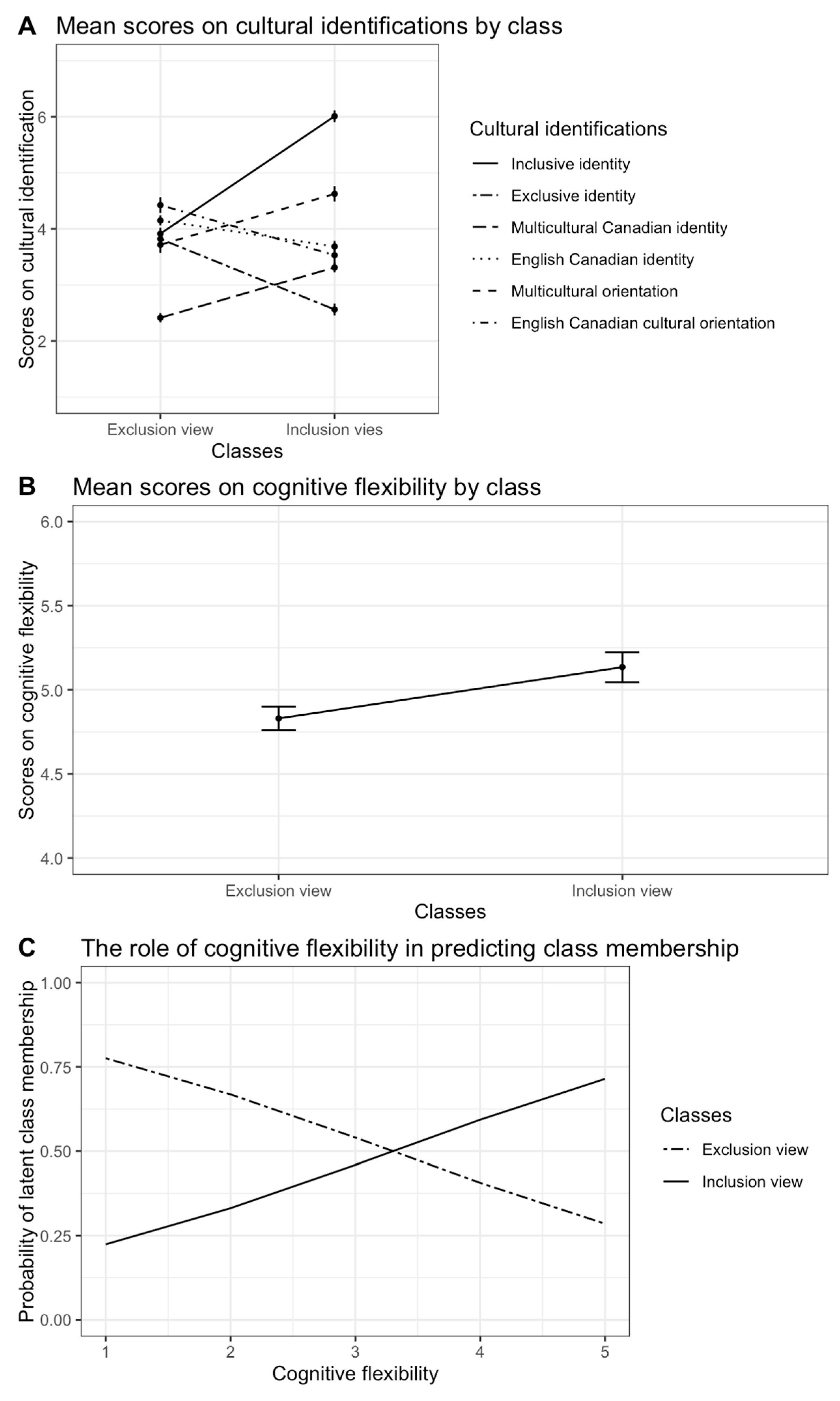

9.2. Latent Class Description and Regressions

10. Discussion

11. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The acculturation orientations traditionally assessed in migrant populations reflect a need to negotiate the feeling of belonging to at least two cultural groups—their heritage cultural group and the local majority group (Berry, 1997, 2005). As such, it allows four possible acculturation strategies that capture simultaneous engagement and identification with heritage and mainstream cultural groups. |

| 2 | It must be noted, however, that this is recent history, rooted in Canada’s colonial past under the UK and France, with First Nations peoples predating European settlement. Although now a small proportion of the population, Indigenous communities have played a key role in shaping national identity, reconciliation efforts, and Canada’s evolving approach to multiculturalism. |

References

- Adorno, T. W. (1950). Types and syndroms. In The authoritarian personality (pp. 744–783). Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, R. (2009). Blurring the color line: The new chance for a more integrated America. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities. Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. (2020). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. In The new social theory reader (2nd ed., pp. 282–288). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardag, M. M., Cohrs, J. C., & Selck, T. J. (2019). A multi-method approach to national identity: From individual level attachment to national attachment. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, S. C., Stathi, S., & Golec de Zavala, A. (2023). Social identity threat across group status: Links to psychological well-being and intergroup bias through collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(2), 208–220. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2022-10713-001 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., & Gayles, J. G. (2010). Variable-centered and person-centered approaches to studying Mexican-origin mother–daughter cultural orientation dissonance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1274–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A. B. I., & Presbitero, A. (2018). Cognitive flexibility and cultural intelligence: Exploring the cognitive aspects of effective functioning in culturally diverse contexts. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. Balls Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2017). Theories and models of acculturation. In S. J. Schwartz, & J. Unger (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of acculturation and health (pp. 15–28). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J. C. (1981). Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bonikowski, B., & DiMaggio, P. (2016). Varieties of American popular nationalism. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 949–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braem, S., & Egner, T. (2018). Getting a grip on cognitive flexibility. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(6), 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L., & Dewing, M. (2018). Canadian multiculturalism. Library of Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M. M., Kung, F. Y., & Yao, D. J. (2015). Understanding the divergent effects of multicultural exposure. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, J., Johnston, R., & Wright, M. (2012). Do patriotism and multiculturalism collide? Competing perspectives from Canada and the United States. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 45(3), 531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S., & Muthén, B. (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014). Discrimination divides across identity dimensions: Perceived racism reduces support for gay rights and increases anti-gay bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demes, K. A., & Geeraert, N. (2014). Measures matter: Scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and acculturation orientation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(1), 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J. P., & Vander Wal, J. S. (2010). The cognitive flexibility inventory: Instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(3), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, T., Gavin, K., & Quintana, F. J. (2010). Say “adios” to the American dream? The interplay between ethnic and national identity among Latino and Caucasian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucerain, M. M. (2019). Moving forward in acculturation research by integrating insights from cultural psychology. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 73, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucerain, M. M., Amiot, C. E., Thomas, E. F., & Louis, W. R. (2018). What it means to be American: Identity inclusiveness/exclusiveness and support for policies about Muslims among US-born Whites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 18(1), 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, M. W., & Torres, L. (2022). Cultural adaptation profiles among Mexican-descent Latinxs: Acculturation, acculturative stress, and depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 28(2), 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziak, J. J., Lanza, S. T., & Tan, X. (2014). Effect size, statistical power, and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiranen, R. (2022). Emotions and nationalism. In The routledge history of emotions in the modern world (pp. 407–422). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, B. D., Maddox, W. T., & Love, B. C. (2013). Real-time strategy game training: Emergence of a cognitive flexibility trait. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e70350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, L. K., & Ponizovskiy, V. (2018). The three facets of national identity: Identity dynamics and attitudes toward immigrants in Russia. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 59(5–6), 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q., & Pietsch, J. (2024). Representing diversity in a liberal democracy: A case study of Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 50(12), 3069–3090. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. (2005). Dimensions of Taiwanese/Chinese identity and national identity in Taiwan. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 40(1–2), 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelicato, A., & Martín, J. C. (2023). The effects of three facets of national identity and other socioeconomic traits on attitudes towards immigrants. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue De L Integration Et De La Migration Internationale, 25(2), 645–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaki, T., Kim, M., Lamont, A., George, M., Chang, C., Feaster, D., & Van Horn, M. L. (2018). The effects of sample size on the estimation of regression mixture models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(2), 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnco, C., Wuthrich, V. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2014). Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppke, C. (2005). Selecting by origin: Ethnic migration in the liberal state. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, R. E., & Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Koenker, R. (2005). Quantile regression (Econometric Society Monographs; No. 38). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J. R., Coenen, A. C., Gundersen, A., & Obaidi, M. (2023). How are acculturation orientations associated among majority-group members? The moderating role of ideology and levels of identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 96, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., Sam, D. L., Berry, J. W., & Dovidio, J. F. (2021). The missing side of acculturation: How majority-group members relate to immigrant and minority-group cultures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, W. (1998). Ethnic associations and democratic citizenship. In Freedom of association (pp. 177–213). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landemore, H. (2018). What does it mean to take diversity seriously: On open-mindedness as a civic virtue. Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy, 16, 795–802. [Google Scholar]

- Lefringhausen, K., Ferenczi, N., Marshall, T. C., & Kunst, J. R. (2021). A new route towards more harmonious intergroup relationships in England? Majority members’ proximal-acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 82, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefringhausen, K., & Marshall, T. C. (2016). Locals’ bidimensional acculturation model: Validation and associations with psychological and sociocultural adjustment outcomes. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(4), 356–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lefringhausen, K., Marshall, T. C., Ferenczi, N., Zagefka, H., & Kunst, J. R. (2023). Majority members’ acculturation: How proximal-acculturation relates to expectations of immigrants and intergroup ideologies over time. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 26(5), 953–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C. H., & Ward, C. (2000). Identity conflict in sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24(6), 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C., Ley, C., Klein, O., Bernard, P., & Licata, L. (2013). Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(4), 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, D. A., & Lewis, J. B. (2011). poLCA: An R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(10), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Wei, M. (2020). Cognitive flexibility, relativistic appreciation, and ethnocultural empathy among Chinese international students. Counseling Psychologist, 48(4), 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L., Shao, B., & Thomas, D. C. (2019). The role of early immersive culture mixing in cultural identifications of multiculturals. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(4), 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. M., & Rubin, R. B. (1995). A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Reports, 76, 623–626. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, S., Webb, M., & Brown, D. (2012). All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, L. (2017). Immigration, national identity and political trust in European democracies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(3), 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvetskaya, A., Stora, L., & Doucerain, M. M. (under review). The role of place and psychological flexibility in predicting multicultural identification patterns: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, M. (2002). Measuring national identity and patterns of attachment: Quebec and nationalist mobilization. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 8(3), 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mepham, K. D., & Martinovic, B. (2018). Multilingualism and out-group acceptance: The mediating roles of cognitive flexibility and deprovincialization. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 37(1), 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modood, T. (2024). The future of multiracial democracy: The rise of multicultural nationalism. Journal of Democracy, 35(4), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. B. (2015). Mixed mode latent class analysis: An examination of fit index performance for classification. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(1), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummendey, A., & Otten, S. (1998). Positive–negative asymmetry in social discrimination. European Review of Social Psychology, 9(1), 107–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, K. W., Oddi, K. B., & Bridgett, D. J. (2013). Cognitive correlates of personality: Links between executive functioning and the big five personality traits. Journal of Individual Differences, 34(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A. M. D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2010). Multicultural identity: What it is and why it matters. In The psychology of social and cultural diversity (pp. 85–114). Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, S. (2018). Identity paradiplomacy in Québec. Quebec Studies, 66, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehrson, S., & Green, E. G. T. (2010). Who we are and who can join us: National identity content and entry criteria for new immigrants. Journal of Social Issues, 66(4), 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehrson, S., Vignoles, V. L., & Brown, R. (2009). National identification and anti-immigrant prejudice: Individual and contextual effects of national definitions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pekerti, A. A. (2019). Double-edges of acculturation from the n-culturals’ lens. In n-culturalism in managing work and life (pp. 49–62). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, I. R., Carvalho, C. L., Dias, C., Lopes, P., Alves, S., de Carvalho, C., & Marques, J. M. (2020). A path toward inclusive social cohesion: The role of European and national identity on contesting vs. accepting European migration policies in Portugal. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1875. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Rende, B. (2000). Cognitive flexibility: Theory, assessment, and treatment. Seminars in Speech and Language, 21(2), 0121–0153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D. W., & Grant, P. R. (2023). Bicultural identity: A social identity review. Psicologia Sociale, 18(1), 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. (1948). Generalized mental rigidity as a factor in ethnocentrism. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 43(3), 259. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M. C. (2010). Multiculturalism in the canadian forces: An evolution from obligation to opportunity (Research Project). Canadian Forces College. [Google Scholar]

- Sindic, D., & Condor, S. (2014). Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorisation Theory. In P. Nesbitt-Larking, C. Kinnvall, T. Capelos, & H. Dekker (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of global political psychology. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. D. (1991). National identity. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman, D. J., Eidelman, S., Dueweke, A. R., Marin, M. S., & Dominguez, B. (2019). Open to diversity: Openness to experience predicts beliefs in multiculturalism and colorblindness through perspective taking. Journal of Individual Differences, 40(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M. L., Näf, J., Michel, L., & Meinshausen, N. (2021). PKLM: A flexible MCAR test using classification. arXiv, arXiv:2109.10150. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2024). Special interest profile. 2021 Census of population. Statistics Canada catalogue No. 98-26-00092021001. Released 20 March 2024. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/sip/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Syed, M. (2013). Identity exploration, identity confusion, and openness as predictors of multicultural ideology. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(4), 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. (1991). 4. Shared and divergent values. In R. Watts, & D. Brown (Eds.), Options for a new Canada (pp. 53–76). University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropp, L. R., & Wright, S. C. (2001). Ingroup identification as the inclusion of ingroup in the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(5), 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, F. J., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Feltzer, M. J. (1999). Acculturation and cognitive performance of migrant children in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology, 34(3), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hiel, A., Onraet, E., Crowson, H. M., & Roets, A. (2016). The relationship between right–wing attitudes and cognitive style: A comparison of self–report and behavioural measures of rigidity and intolerance of ambiguity. European Journal of Personality, 30(6), 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P., Prins, K. S., & Buunk, B. P. (1998). Attitudes of minority and majority members towards adaptation of immigrants. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28(6), 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. (2018). The benefits of studying immigration for social psychology. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2002). Latent class cluster analysis. In Applied latent class analysis (pp. 89–106). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, K. T. T., Malulani Castro, K., Cheah, C. S. L., & Yu, J. (2019). Mediating and moderating processes in the associations between Chinese immigrant mothers’ acculturation and parenting styles in the United States. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(4), 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeman, J. (2021). The Middle East in Canadian foreign policy and national identity formation. International Journal, 76(3), 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, A. (2002). Nationalist exclusion and ethnic conflict: Shadows of modernity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wurpts, I. C., & Geiser, C. (2014). Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. C. (2006). Evaluating latent class analysis models in qualitative phenotype identification. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 50(4), 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeeswaran, K., & Dasgupta, N. (2015). Conceptions of national identity in a globalised world: Antecedents and consequences. European Review of Social Psychology, 25, 189–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeeswaran, K., Dasgupta, N., Adelman, L., Eccleston, A., & Parker, M. T. (2011). To be or not to be (ethnic): Public vs. private expressions of ethnic identification differentially impact national inclusion of white and non-white groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., & Wang, S. (2011). An investigation into the acculturation strategies sf Chinese Students in Germany. Intercultural Communication Studies, 20(2), 190. [Google Scholar]

- Zmigrod, L., Rentfrow, P. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2019). Cognitive inflexibility predicts extremist attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Latent Classes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Size of the smallest class, % | 42.87 | 21.18 | 7.89 |

| Maximum Log-Likelihood | −1871.83 | −1826.46 | −1795.34 |

| No. of Estimated Parameters | 68 | 104 | 140 |

| AIC a | 3879.67 | 3860.92 | 3870.67 |

| BIC a | 4104.63 | 4204.98 | 4333.83 |

| Mean posterior probability | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| Relative Entropy | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Bootstrap LRT, p Value b, c | – | 0.33 | 0.35 |

| Variable | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 34.89 (13.00) | |||||||

| 2. English Canadian identification | 3.93 (0.97) | 0.12 | ||||||

| [−0.02, 0.25] | ||||||||

| 3. Multicultural identification | 2.83 (0.97) | −0.04 | −0.05 | |||||

| [−0.18, 0.10] | [−0.18, 0.09] | |||||||

| 4. Canadian ID inclusiveness | 4.90 (1.43) | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.34 ** | ||||

| [−0.25, 0.03] | [−0.24, 0.03] | [0.21, 0.45] | ||||||

| 5. Canadian ID exclusiveness | 3.21 (1.30) | 0.02 | 0.14 * | −0.11 | −0.39 ** | |||

| [−0.12, 0.16] | [0.00, 0.28] | [−0.25, 0.03] | [−0.50, −0.27] | |||||

| 6. BAOS-H | 4.02 (1.56) | 0.15 * | 0.27 ** | 0.05 | −0.15 * | 0.27 ** | ||

| [0.01, 0.28] | [0.14, 0.40] | [−0.09, 0.19] | [−0.29, −0.02] | [0.14, 0.40] | ||||

| 7. BAOS-M | 4.15 (1.52) | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.48 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.15 * | 0.16 * | |

| [−0.26, 0.01] | [−0.17, 0.11] | [0.36, 0.58] | [0.11, 0.37] | [−0.28, −0.01] | [0.02, 0.29] | |||

| 8. Cognitive flexibility | 4.98 (0.81) | 0.23 ** | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| [0.09, 0.35] | [−0.18, 0.10] | [−0.00, 0.27] | [−0.04, 0.24] | [−0.07, 0.20] | [−0.09, 0.18] | [−0.08, 0.19] |

| Inclusion View vs. Exclusion View | ||

|---|---|---|

| Covariates | OR (SE) | p |

| Gender (female) | 1.04 (0.47) | 0.24 |

| Age, years | 0.97 (0.01) | 0.074 |

| CFS | 1.77 (0.27) | 0.037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medvetskaya, A.; Ryder, A.G.; Doucerain, M.M. Thinking Outside the Nation: Cognitive Flexibility’s Role in National Identity Inclusiveness as a Marker of Majority Group Acculturation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040498

Medvetskaya A, Ryder AG, Doucerain MM. Thinking Outside the Nation: Cognitive Flexibility’s Role in National Identity Inclusiveness as a Marker of Majority Group Acculturation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040498

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedvetskaya, Anna, Andrew G. Ryder, and Marina M. Doucerain. 2025. "Thinking Outside the Nation: Cognitive Flexibility’s Role in National Identity Inclusiveness as a Marker of Majority Group Acculturation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040498

APA StyleMedvetskaya, A., Ryder, A. G., & Doucerain, M. M. (2025). Thinking Outside the Nation: Cognitive Flexibility’s Role in National Identity Inclusiveness as a Marker of Majority Group Acculturation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040498