The Public Service Motivation’s Impact on Turnover Intention in Korean Public Organizations: Do Perceived Organizational Politics Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

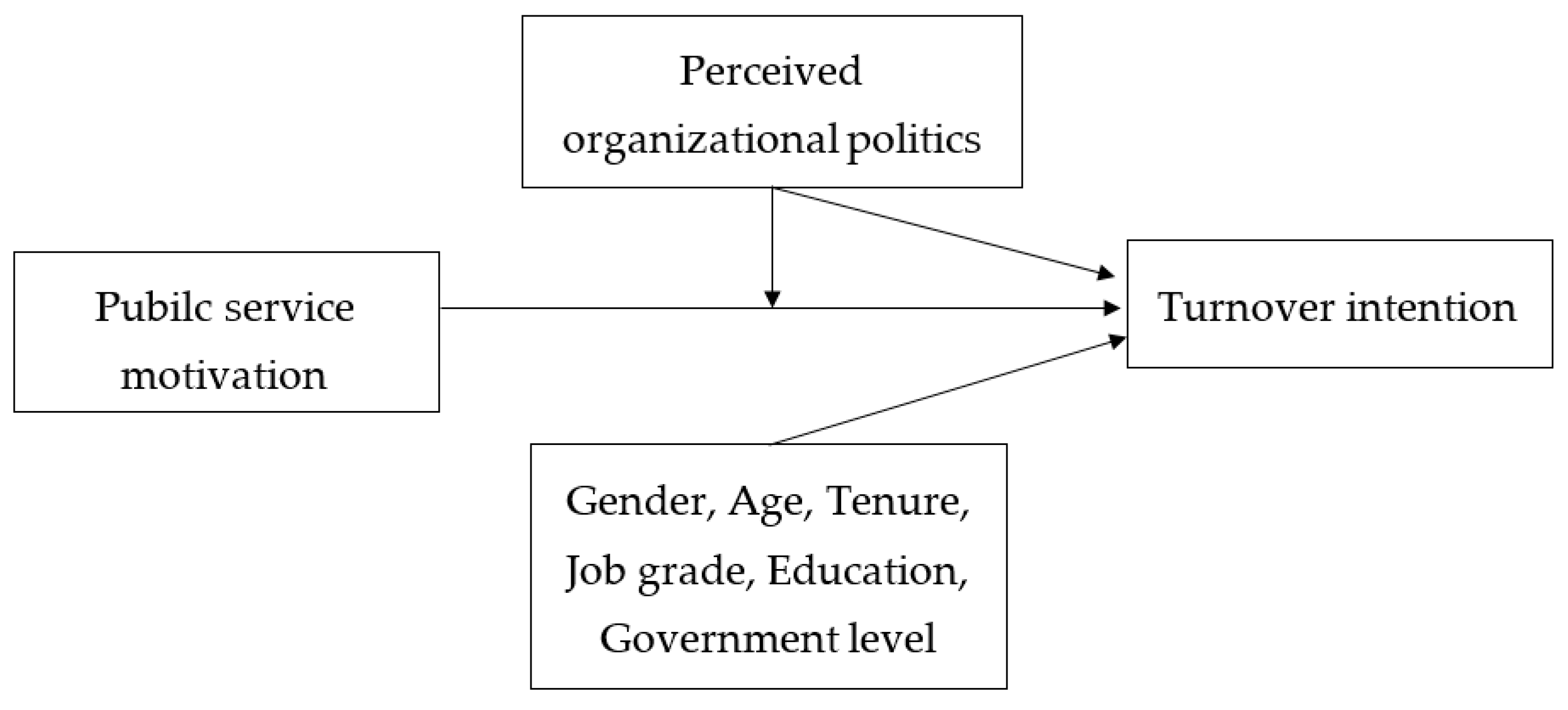

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Public Service Motivation on Turnover Intention

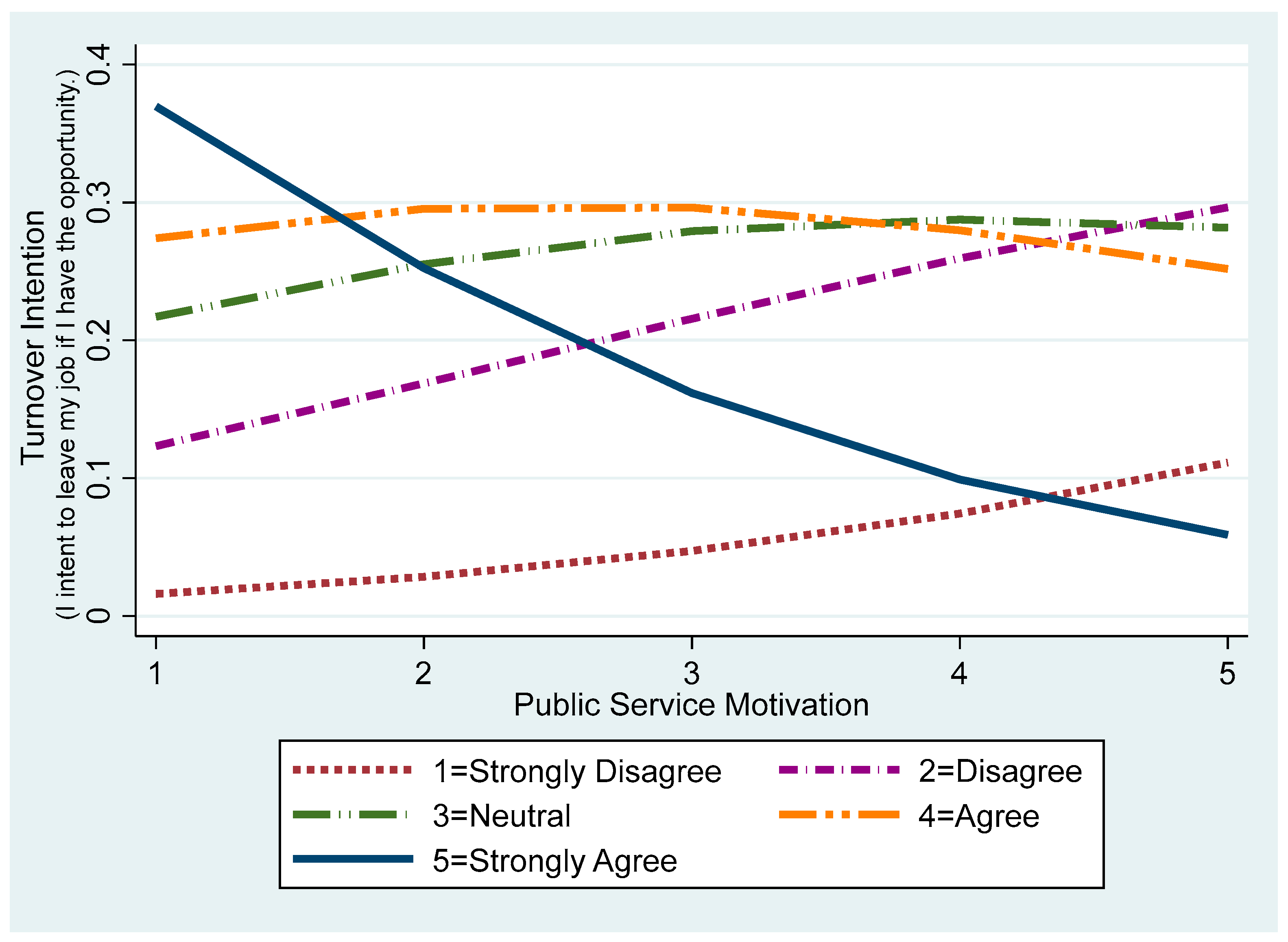

2.2. Moderating Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics

3. Model Specification

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Dependent Variable: Turnover Intention

3.3.2. Independent Variable: Public Service Motivation

3.3.3. Moderating Variable: Perceived Organizational Politics

3.3.4. Control Variables

3.3.5. Measurement Reliability and Validity

3.4. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. International Context and Applicability

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ananth, C. V., & Kleinbaum, D. G. (1997). Regression models for ordinal responses: A review of methods and applications. International Journal of Epidemiology, 26(6), 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R., Boyne, G., & Mostafa, A. M. S. (2017). When bureaucracy matters for organizational performance: Exploring the benefits of administrative intensity in big and complex organizations. Public Administration, 95(1), 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., & Budhwar, P. S. (2004). Exchange fairness and employee performance: An examination of the relationship between organizational politics and procedural justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, S., Bel, G., & Esteve, M. (2020). The benefits of PSM: An oasis or a mirage? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(4), 619–635. [Google Scholar]

- Ballart, X., & Ripoll, G. (2024). Transformational leadership, basic needs satisfaction and public service motivation: Evidence from social workers in Catalonia. International Journal of Public Administration, 47(12), 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekke, A. J. G. M., & Meer, F. M. (2000). Civil service systems in Western Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G. A., Selden, S. C., & Facer Ii, R. L. (2000). Individual conceptions of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 60(3), 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. (2008). Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, E. (2007). Antecedents affecting public service motivation. Personnel Review, 36(3), 356–377. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. W., & Im, T. (2016). PSM and turnover intention in public organizations: Does change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior play a role? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(4), 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. W., Im, T., & Jeong, J. (2014). Internal efficiency and turnover intention: Evidence from local government in South Korea. Public Personnel Management, 43(2), 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H., Rosen, C. C., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. J., & Lewis, G. B. (2012). Turnover intention and turnover behavior: Implications for retaining federal employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(1), 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. (2020). Korean civil service systems from recruitment to retirement. In C. Moon, & M. J. Moon (Eds.), The routledge handbook of Korean politics and public administration (pp. 259–274). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chordiya, R. (2022). A study of interracial differences in turnover intentions: The Mitigating role of pro-diversity and justice-oriented management. Public Personnel Management, 51(2), 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R. K., Paarlberg, L., & Perry, J. L. (2017). Public service motivation research: Lessons for practice. Public Administration Review, 77(4), 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J. I., Lee, S.-Y., & Lee, H. (2022). Critical latent triggers for threshold candidates at exit? A study of Korean public employees. International Review of Public Administration, 27(4), 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G., Blake, R. S., & Goodman, D. (2016). Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 240–263. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, S., Kluijtmans, T., Meyfroodt, K., & Desmidt, S. (2022). How does organizational sustainability foster public service motivation and job satisfaction? The mediating role of organizational support and societal impact potential. Public Management Review, 24(8), 1155–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., & Pereira, R. (2022). Perceived organizational politics and quitting plans: An examination of the buffering roles of relational and organizational resources. Management Decision, 60(1), 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroux, P. (2022). Employment of senior workers in Japan. Contemporary Japan, 34(1), 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. T., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach, or spearman-brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A., Santinha, G., & Forte, T. (2022). Public service motivation and determining factors to attract and retain health professionals in the public sector: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G. R., Adams, G., Kolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W. A., & Ammeter, A. P. (2002). Perceptions of organizational politics: Theory and research directions. In The many faces of multi-level issues (Volume 1, pp. 179–254). JAI Press/Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, G. R., Harrell-Cook, G., & Dulebohn, J. H. (2000). Organizational politics: The nature of the relationship between politics perceptions and political behavior. In Research in the sociology of organizations (pp. 89–130). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, G. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (1992). Perceptions of organizational politics. Journal of Management, 18(1), 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, H. G. (2002). Confucius and the moral basis of bureaucracy. Administration & Society, 33(6), 610–628. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, T.-S., & Moon, K.-K. (2023). Organizational justice and employee voluntary absenteeism in public sector organizations: Disentangling the moderating roles of work motivation. Sustainability, 15(11), 8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameduddin, T., & Engbers, T. (2022). Leadership and public service motivation: A systematic synthesis. International Public Management Journal, 25(1), 86–119. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, M. B., Herst, D. E., Parola, H. R., & Carmona, B. P. (2017). Organizational correlates of public service motivation: A meta-analysis of two decades of empirical research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 27(1), 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. J., Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2007). The moderating effects of justice on the relationship between organizational politics and workplace attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwarter, W. A., Rosen, C. C., Jordan, S. L., Ferris, G. R., Ejaz, A., & Maher, L. P. (2020). Perceptions of organizational politics research: Past, present, and future. Journal of Management, 46(6), 879–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, A. (2015). Employment relations in the UK civil service. Personnel Review, 44(6), 930–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P. W., Griffeth, R. W., & Sellaro, C. L. (1984). The validity of Mobley’s (1977) model of employee turnover. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34(2), 141–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homberg, F., McCarthy, D., & Tabvuma, V. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, S. (2011). Contrasting Anglo-American and continental European civil service systems. In A. Massey (Ed.), International handbook on civil service systems (pp. 31–54). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. J. (2000). Public-service motivation: A multivariate test. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(4), 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, H., & Abner, G. (2024). What makes public employees want to leave their job? A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among public sector employees. Public Administration Review, 84(1), 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S. H. (2024). Citizens as co-producers of public service culture: How citizen incivility affects public employee motivations to stay and serve. Public Integrity, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C. S. (2010). Predicting organizational actual turnover rates in the U.S. federal government. International Public Management Journal, 13(3), 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, W., Borry, E. L., & DeHart-Davis, L. (2019). More than pathological formalization: Understanding organizational structure and red tape. Public Administration Review, 79(2), 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. (2009). Testing the structure of public service motivation in Korea: A research note. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(4), 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. (2012). Does person-organization fit matter in the public-sector? Testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit in the relationship between public service motivation and work attitudes. Public Administration Review, 72(6), 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., & Vandenabeele, W. (2010). A Strategy for building public service motivation research internationally. Public Administration Review, 70(5), 701–709. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, K., & Han, L. (2013). An empirical study on public service motivation of the next generation civil servants in China. Public Personnel Management, 42(2), 191–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeong, K., & Kim, M. (2022). Why and how are millennials sensitive to unfairness? Focusing on the moderated mediating role of generation on turnover intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration, 46(3), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1994). An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S. (2015). How have careers changed? An investigation of changing career patterns across four generations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(1), 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P. (1980). Regression models for ordinal data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 42(2), 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K. J., & Hicklin, A. (2008). Employee turnover and organizational performance: Testing a hypothesis from classical public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Meisler, G., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2014). Perceived organizational politics, emotional intelligence and work outcomes: Empirical exploration of direct and indirect effects. Personnel Review, 43(1), 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B. K., Rutherford, M. A., & Kolodinsky, R. W. (2008). Perceptions of organizational politics: A meta-analysis of outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22(3), 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. The Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 226–256. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D. P., & Landuyt, N. (2008). Explaining turnover intention in state government: Examining the roles of gender, life cycle, and loyalty. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 28(2), 120–143. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., & Lee, K.-H. (2020). Organizational politics, work attitudes and performance: The moderating role of age and public service motivation (PSM). International Review of Public Administration, 25(2), 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review, 50(3), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B. G. (2018). The politics of bureaucracy: An introduction to comparative public administration. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, D., Marvel, J., & Fernandez, S. (2011). So hard to say goodbye? Turnover intention among U.S. federal employees. Public Administration Review, 71(5), 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Quratulain, S., Khan, A. K., & Sabharwal, M. (2019). Procedural fairness, public service motives, and employee work outcomes: Evidence from pakistani public service organizations. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 39(2), 276–299. [Google Scholar]

- Raadschelders, J. C. (2009). Trends in the American study of public administration: What could they mean for Korean public administration? Korean Journal of Policy Studies, 23(2), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H. G. (2014). Understanding and managing public organizations (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt, B., & Beierlein, C. (2014). Can’t we make it any shorter? Journal of Individual Differences, 35(4), 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ritz, A., Brewer, G. A., & Neumann, O. (2016). Public service motivation: A systematic literature review and outlook. Public Administration Review, 76(3), 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, D. C., Park, H. H., & Eom, T. H. (2017). Street-level bureaucrats’ turnover intention: Does public service motivation matter? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(3), 563–582. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R., & Wang, W. (2017). Transformational leadership, employee turnover intention, and actual voluntary turnover in public organizations. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1124–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K., & Hur, H. (2020). Bureaucratic structures and organizational commitment: Findings from a comparative study of 20 European countries. Public Management Review, 22(6), 877–907. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H., An, S., Zhang, L., Xiao, Y., & Li, X. (2024). The Antecedents and outcomes of public service motivation: A meta-analysis using the job demands–resources model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 861. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W., Hsieh, C.-W., Chen, C.-A., & Wen, B. (2024). Public service motivation, performance-contingent pay, and job satisfaction of street-level bureaucrats. Public Personnel Management, 53(2), 256–280. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Walle, S., Steijn, B., & Jilke, S. (2015). Extrinsic motivation, PSM and labour market characteristics: A multilevel model of public sector employment preference in 26 countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(4), 833–855. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele, W. (2007). Toward a public administration theory of public service motivation: An institutional approach. Public Management Review, 9(4), 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2000). Organizational politics, job attitudes, and work outcomes: Exploration and implications for the public sector. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57(3), 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2007). Leadership style, organizational politics, and employees’ performance: An empirical examination of two competing models. Personnel Review, 36(5), 661–683. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Kapun, D. (2005). Perceptions of politics and perceived performance in public and private organisations: A test of one model across two sectors. Policy & Politics, 33(2), 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Talmud, I. (2010). Organizational politics and job outcomes: The moderating effect of trust and social support. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(11), 2829–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-M., Van Witteloostuijn, A., & Heine, F. (2020). A moral theory of public service motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 517763. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E., & Wong, W. (1998). Public administration in a global context: Bridging the gaps of theory and practice between Western and non-Western nations. Public Administration Review, 58(1), 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B. E., Christensen, R. K., & Pandey, S. K. (2013). Measuring public service motivation: Exploring the equivalence of existing global measures. International Public Management Journal, 16(2), 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J. A. (Claire), Lee, Y., & Mastracci, S. (2019). The moderating effect of female managers on job stress and emotional labor for public employees in gendered organizations: Evidence from Korea. Public Personnel Management, 48(4), 535–564. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Subcategory | Number of Cases | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3444 | 53.45 |

| Female | 3000 | 46.55 | |

| Age | ≤29 | 700 | 10.86 |

| 30–39 | 2472 | 38.36 | |

| 40–49 | 1999 | 31.02 | |

| ≥50 | 1273 | 19.75 | |

| Tenure | ≤5 | 1924 | 29.86 |

| 6–10 | 1499 | 23.26 | |

| 11–15 | 808 | 12.54 | |

| 16–20 | 985 | 15.29 | |

| 21–25 | 393 | 6.10 | |

| ≥26 | 835 | 12.96 | |

| Job grade | 1–4 | 200 | 3.10 |

| 5 | 917 | 14.23 | |

| 6–7 | 3664 | 56.86 | |

| 8–9 | 1663 | 25.81 | |

| Education | High school or below | 319 | 4.95 |

| Associate’s degree | 315 | 4.89 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5053 | 78.41 | |

| Master’s degree | 646 | 10.02 | |

| Doctorate | 111 | 1.72 | |

| Government level | Central | 1673 | 44.35 |

| Local | 2099 | 55.65 |

| Latent Variables | Survey Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public service motivation |

| 0.829 | - |

| 0.850 | - | |

| 0.860 | - | |

| 0.845 | - | |

| 0.719 | - | |

| Perceived organizational politics |

| - | 0.905 |

| - | 0.898 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1 | ||||||||

| (2) | −0.204 *** | 1 | |||||||

| (3) | 0.141 *** | −0.115 *** | 1 | ||||||

| (4) | 0.032 *** | −0.113 *** | 0.077 *** | 1 | |||||

| (5) | −0.210 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.018 * | −0.143 *** | 1 | ||||

| (6) | −0.218 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.012 | −0.051 *** | 0.840 *** | 1 | |||

| (7) | 0.145 *** | −0.163 *** | −0.012 * | 0.099 *** | −0.498 *** | −0.514 *** | 1 | ||

| (8) | 0.032 * | 0.105 *** | −0.007 | −0.007 | 0.223 *** | 0.121 *** | −0.283 *** | 1 | |

| (9) | −0.025 | 0.029 * | −0.039 ** | 0.004 | −0.042 ** | −0.090 *** | −0.234 *** | 0.152 *** | 1 |

| mean | 3.331 | 3.139 | 2.906 | 0.466 | 2.597 | 2.834 | 3.054 | 2.987 | 0.556 |

| s.d. | 1.141 | 0.727 | 0.874 | 0.499 | 0.924 | 1.721 | 0.722 | 0.645 | 0.497 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | ||||

| (S.E.) | (S.E.) | (S.E.) | ||||

| Gender (female = 1) | −0.057 | −0.153 | −0.145 | |||

| (0.135) | (0.140) | (0.139) | ||||

| Age | −0.514 | *** | −0.426 | *** | −0.413 | *** |

| (0.137) | (0.143) | (0.141) | ||||

| Tenure | −0.311 | *** | −0.299 | *** | −0.305 | *** |

| (0.076) | (0.079) | (0.078) | ||||

| Job grade | 0.276 | ** | 0.277 | ** | 0.266 | ** |

| (0.117) | (0.122) | (0.121) | ||||

| Education | 0.606 | *** | 0.703 | *** | 0.703 | *** |

| (0.110) | (0.116) | (0.116) | ||||

| Government level | −0.348 | ** | −0.282 | * | −0.278 | * |

| (0.143) | (0.149) | (0.147) | ||||

| Perceived organizational politics (A) | 0.703 | *** | 0.662 | *** | −0.125 | |

| (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.280) | ||||

| Public service motivation (B) | −0.995 | *** | −1.735 | *** | ||

| (0.106) | (0.280) | |||||

| (A) × (B) | 0.247 | *** | ||||

| (0.085) | ||||||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0.760 | 0.728 | 0.737 | ||||

| 0.542 | 0.556 | 0.578 | ||||

| 0.431 | 0.465 | 0.486 | ||||

| 1.094 | −1.608 | −3.973 | ||||

| 2.088 | 0.123 | −1.620 | ||||

| 1.874 | 0.474 | −0.898 | ||||

| 1.676 | 0.567 | −0.587 | ||||

| Log likelihood | −5498.421 | −5445.518 | −5541.384 | |||

| Wald | 199.320 | *** | 275.210 | *** | 291.280 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, J.-Y.; Moon, K.-K. The Public Service Motivation’s Impact on Turnover Intention in Korean Public Organizations: Do Perceived Organizational Politics Matter? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040474

Lim J-Y, Moon K-K. The Public Service Motivation’s Impact on Turnover Intention in Korean Public Organizations: Do Perceived Organizational Politics Matter? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040474

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Jae-Young, and Kuk-Kyoung Moon. 2025. "The Public Service Motivation’s Impact on Turnover Intention in Korean Public Organizations: Do Perceived Organizational Politics Matter?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040474

APA StyleLim, J.-Y., & Moon, K.-K. (2025). The Public Service Motivation’s Impact on Turnover Intention in Korean Public Organizations: Do Perceived Organizational Politics Matter? Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040474