Individual and Contextual Morality: How Educators in Oppositional and Permissive Communities Use Culturally Responsive Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Diversity Ideologies Provide Individual Moral Frameworks

1.2. Contextual Moral Frameworks Shape Individuals’ Experiences and Behaviors

1.3. DEI Opposition Shapes Individual Awareness and Practices

1.4. Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Diversity Beliefs

2.2.2. Culturally Responsive Practices

2.2.3. Administrator Support for Educational Equity

2.2.4. Political Climate for DEI

2.3. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Educators with Varying Moral Beliefs About Diversity

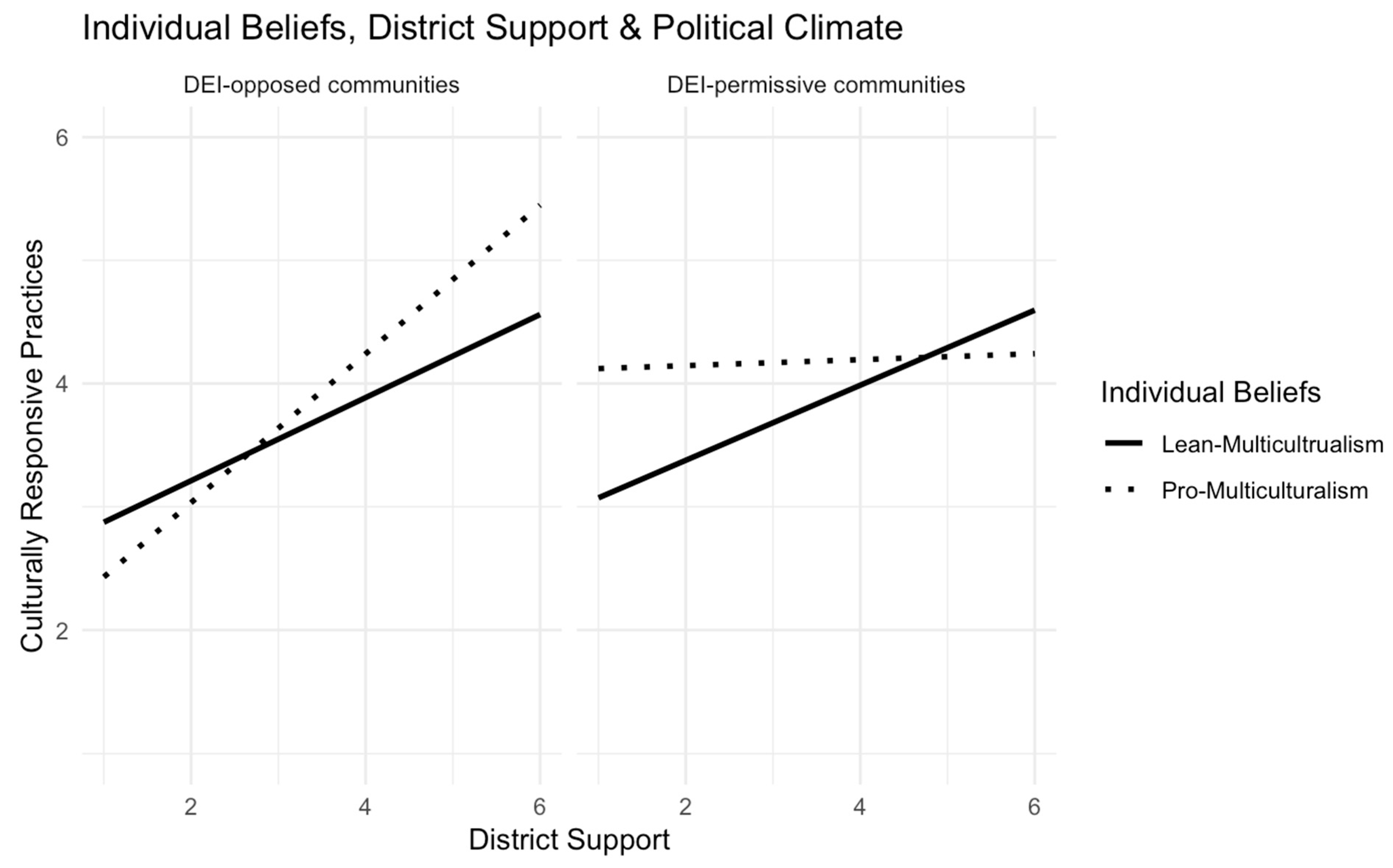

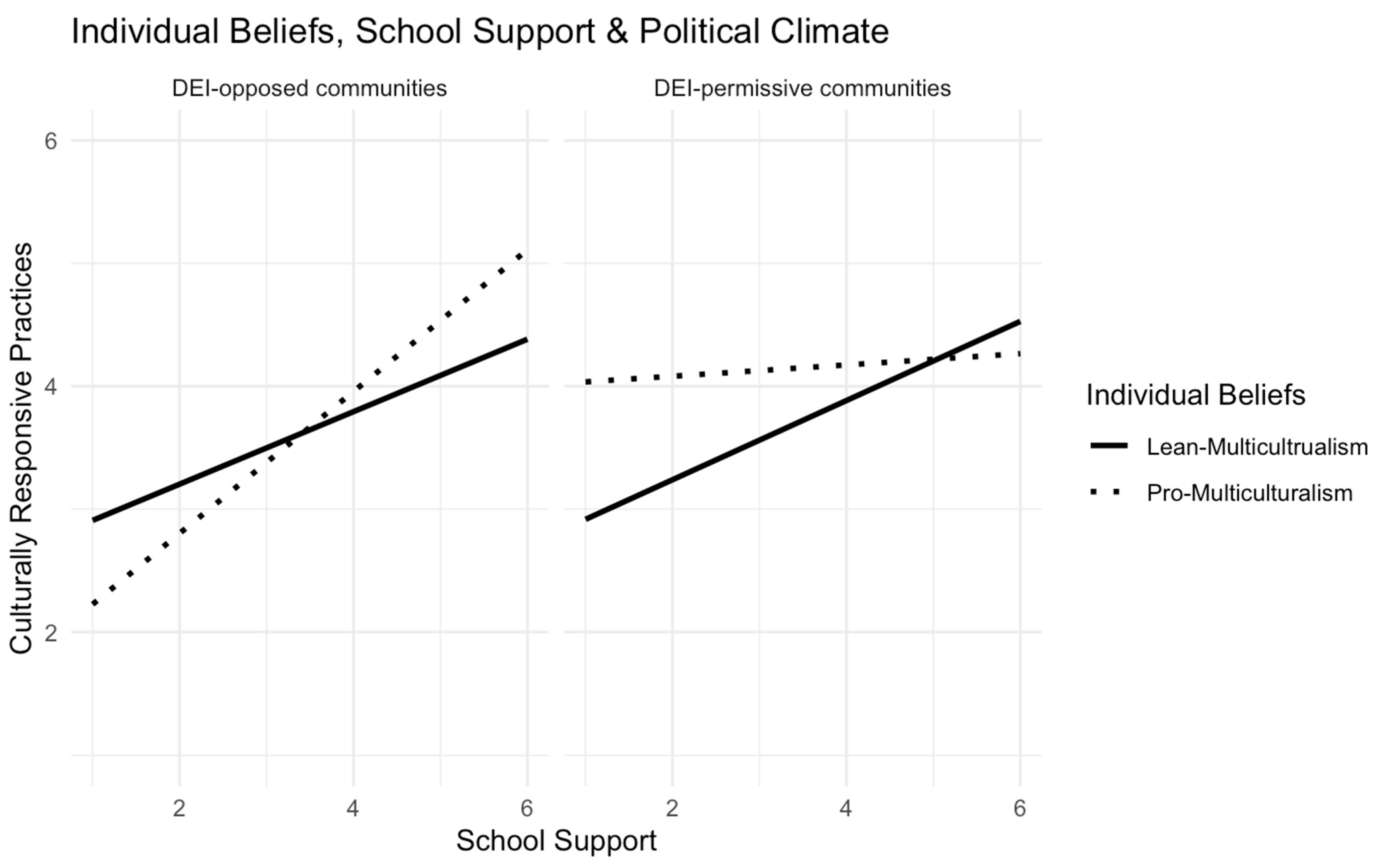

3.2. Individual Beliefs, Administrator Support, and Political Climate Jointly Predict Educators’ Implementation of Culturally Responsive Practices

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Within this paper, we conceptualize students from marginalized backgrounds as racial/ethnic minority students (e.g., students who are Black, Hispanic/Latine, or Native American) and students from lower-income families (Fluit et al., 2024). |

References

- Abacioglu, C. S., Volman, M., & Fischer, A. H. (2020). Teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perspective taking abilities as factors in culturally responsive teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 736–752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akogul, S., & Erisoglu, M. (2017). An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy, 19(9), 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, T. N., Clark, L. B., Flores-Ganley, I., Harris, C., Kohli, J., McLelland, L., Moody, P., Powell, N., Smith, M., & Zatz, N. (2024). CRT forward tracking project. UCLA school of law critical race studies program. Available online: www.crtforward.law.ucla.edu (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Apfelbaum, E. P., Stephens, N. M., & Reagans, R. E. (2016). Beyond one-size-fits-all: Tailoring diversity approaches to social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, O. R., Dovidio, J. F., & Graham, M. J. (2017). Colorblind and multicultural ideologies are associated with faculty adoption of inclusive teaching practices. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(3), 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, B., & Laughter, J. (2016). The theory and practice of culturally relevant education: A synthesis of research across content areas. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 163–206. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J. A. (2008). An introduction to multicultural education. Available online: https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/preface/0/1/3/4/0134800362.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Birnbaum, H. J., Stephens, N. M., Townsend, S. S. M., & Hamedani, M. G. (2021). A diversity ideology intervention: Multiculturalism reduces the racial achievement gap. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaushild, N. L. (2023). “It’s just something that you have to do as a teacher”: Investigating the intersection of educational infrastructure redesign, teacher discretion, and educational equity in the elementary ELA classroom. The Elementary School Journal, 124(2), 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(11), 1358–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, L. M., Wang, C., Griffiths, C., Yang, J., Markus, H. R., & Fryberg, S. A. (2024). A leadership-level culture cycle intervention changes teachers’ culturally inclusive beliefs and practices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(25), e2322872121. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, C. M. (2017). The complexity of school racial climate: Reliability and validity of a new measure for secondary students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(4), 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Civitillo, S., Juang, L. P., Badra, M., & Schachner, M. K. (2019). The interplay between culturally responsive teaching, cultural diversity beliefs, and self-reflection: A multiple case study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J. S. (2017). Inequality frames: How teachers inhabit color-blind ideology. Sociology of Education, 90(4), 315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, M., Litke, E., Hill, K. L., & Desimone, L. M. (2023). A culturally responsive disposition: How professional learning and teachers’ beliefs about and self-efficacy for culturally responsive teaching relate to instruction. AERA Open, 9, 23328584221140092. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, S. M., & Pray, L. (2017). Learning to teach english language learners: A study of elementary school teachers’ sense-making in an ELL endorsement program. TESOL Quarterly, 51(4), 787–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dismantle DEI Act of 2024, S.4516, 118th Congress. (2024). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4516/text (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Dunn, A. H., Sondel, B., & Baggett, H. C. (2019). “I don’t want to come off as pushing an agenda”: How contexts shaped teachers’ pedagogy in the days after the 2016 U.S. presidential election. American Educational Research Journal, 56(2), 444–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly 46, 229–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluit, S., Cortés-García, L., & von Soest, T. (2024). Social marginalization: A scoping review of 50 years of research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. (2015). The what, why, and how of culturally responsive teaching: International mandates, challenges, and opportunities. Multicultural Education Review, 7(3), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündemir, S., Martin, A. E., & Homan, A. C. (2019). Understanding diversity ideologies from the target’s perspective: A review and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachfeld, A., Hahn, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., & Kunter, M. (2015). Should teachers be colorblind? How multicultural and egalitarian beliefs differentially relate to aspects of teachers’ professional competence for teaching in diverse classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars, M., Maene, C., Stevens, P. A. J., Willems, S., Vantieghem, W., & D’Hondt, F. (2023). Diversity ideologies in Flemish education: Explaining variation in teachers’ implementation of multiculturalism, assimilation and colourblindness. Journal of Education Policy, 38(6), 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, U. M., & Kohli, R. (2023). Silenced and pushed out: The harms of CRT-bans on K-12 teachers. Thresholds in Education, 46(1), 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kehl, J., Krachum Ott, P., Schachner, M., & Civitillo, S. (2024). Culturally responsive teaching in question: A multiple case study examining the complexity and interplay of teacher practices, beliefs, and microaggressions in Germany. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. B., Marchand, A., Taylor, L., & Djonko-Moore, C. (2024). US teacher opposition to so-called critical race theory bans. Teaching and Teacher Education, 151, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Hogan, C. M., & Chow, R. M. (2009). On the malleability of ideology: Motivated construals of color blindness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 857. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Y., & van Koeven, E. (2019). New immigrants. An incentive for intercultural education? Education Inquiry, 10(3), 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L. M., & Flynn, E. (2022). Diversity ideologies, beliefs, and climates: A review, integration, and set of recommendations. Journal of Management, 50(3), 849–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, D. D., Leigh, P. R., Rotheram-Fuller, E., & Cutler, K. D. (2019). The influence of teachers’ colorblind expectations on the political, normative, and technical dimensions of educational reform. International Journal of Educational Reform, 28(1), 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., Steele, C. M., & Steele, D. M. (2000). Colorblindness as a barrier to inclusion: Assimilation and nonimmigrant minorities. Daedalus, 129(4), 233–259. [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy, P., & Hess, D. (2013). Classroom deliberation in an era of political polarization. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(1), 14–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. C., Kroeper, K. M., & Ozier, E. M. (2018). Prejudiced places: How contexts shape inequality and how policy can change them. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. C., & Walton, G. M. (2013). From prejudiced people to prejudiced places: A social-contextual approach to prejudice. In Stereotyping and prejudice. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Musu-Gillette, L., Robinson, J., McFarland, J., KewalRamani, A., Zhang, A., & Wilkinson-Flicker, S. (2016). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2016; (NCES 2016-007); U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016007.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Pandey, S., & Elliott, W. (2010). Suppressor variables in social work research: Ways to identify in multiple regression models. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 1(1), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhouse, H., Lu, C. Y., & Massaro, V. R. (2019). Multicultural education professional development: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 416–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetz, C., & Najarro, I. (2024, May 31). How 9 leaders think about diversity, equity, and inclusion in their schools. Education Week. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/how-9-leaders-think-about-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-their-schools/2024/05 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Peurach, D. J., Yurkofsky, M. M., & Sutherland, D. H. (2019). Organizing and managing for excellence and equity: The work and dilemmas of instructionally focused education systems. Educational Policy, 33(6), 812–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2023 May. Diversity, equity and inclusion in the workplace. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/05/17/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-the-workplace/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Plaut, V. C. (2002). Cultural models of diversity in American: The psychology of difference and inclusion. In R. A. Shweder, M. Minow, & H. R. Markus (Eds.), Engaging cultural differences: The multicultural challenge in liberal democracies (pp. 365–395). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut, V. C., Garnett, F. G., Buffardi, L. E., & Sanchez-Burks, J. (2011). “What about me?” Perceptions of exclusion and Whites’ reactions to multiculturalism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaut, V. C., Thomas, K. M., Hurd, K., & Romano, C. A. (2018). Do color blindness and multiculturalism remedy or foster discrimination and racism? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M. (2023). Supported, silenced, subdued, or speaking up? K12 educators’ experiences with the conflict campaign, 2021–2022. Journal of Leadership, Equity, and Research, 9(2), 4–58. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Sleeter, C. E. (2011). An agenda to strengthen culturally responsive pedagogy. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10(2), 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. L., Ager, J. W., & Williams, D. L. (1992). Suppressor variables in multiple regression/correlation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P., Diamond, J. B., Burch, P., Hallett, T., Jita, L., & Zoltners, J. (2002). Managing in the middle: School leaders and the enactment of accountability policy. Educational Policy, 16(5), 731–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S., & Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: How American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1178–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, N. M., Hamedani, M. G., & Destin, M. (2014). Closing the social-class achievement gap: A difference-education intervention improves first-generation students’ academic performance and all students’ college transition. Psychological Science, 25(4), 943–953. [Google Scholar]

- Vittrup, B. (2016). Early childhood teachers’ approaches to multicultural education & perceived barriers to disseminating anti-bias messages. Multicultural Education, 23, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M. W. (2024). Presidential precinct data for the 2020 election [GitHub dataset]. Available online: https://github.com/TheUpshot/presidential-precinct-map-2020 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Welton, A. D., Diem, S., & Holme, J. J. (2015). Color conscious, cultural blindness: Suburban school districts and demographic change. Education and Urban Society, 47(6), 695–722. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, A., Diliberti, M. K., Lee, S., Kim, B., Lim, J. Z., & Wolfe, R. L. (2023). The diverging state of teaching and learning two years into classroom limitations on race or gender. RAND Corporation, RR-A134-22. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-22.html (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Woo, A., Lee, S., Tuma, A. P., Kaufman, J. H., Lawrence, R. A., & Reed, N. (2022). Walking on eggshells—Teachers’ responses to classroom limitations on race- or gender-related topics. RAND Corporation, RR-A134-16. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-16.html (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Wu, Y., & Apfelbaum, E. P. (2024). Diversity ideologies in organizations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 60, 101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Lean-Multiculturalism (N = 697) | Pro-Multiculturalism (N = 278) | Dual-Belief (N = 82) | Pro-Colorblindness (N = 40) | Overall (N = 1097) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender 1 | Male | 21.7% | 12.2% | 15.9% | 37.5% | 19.4% |

| Female | 78.2% | 86.7% | 85.4% | 62.5% | 80.3% | |

| Race 2 | White | 77.3% | 78.4% | 54.9% | 87.5% | 76.3% |

| Black/African American | 12.2% | 14.4% | 19.5% | 0% | 12.9% | |

| Hispanic/Latine American | 10.8% | 7.6% | 14.6% | 5% | 10.0% | |

| Asian American | 4.3% | 3.2% | 7.3% | 7.5% | 4.4% | |

| Native American | 1.7% | 2.2% | 2.4% | 7.5% | 2.1% | |

| Education | 2-year degree (associate’s) | 14.6% | 7.2% | 15.9% | 5% | 12.5% |

| 4-year degree (bachelor’s) | 38.7% | 33.8% | 42.7% | 42.5% | 37.9% | |

| Master’s degree | 34.7% | 52.9% | 22.0% | 35% | 38.4% | |

| Doctoral degree | 3.3% | 2.5% | 8.5% | 10% | 3.7% | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.90 *** (0.12) | 3.87 *** (0.13) | 3.85 *** (0.13) | 3.85 *** (0.14) | 3.83 *** (0.14) |

| Race (0 = White; 1 = non-White) | 0.12 (0.15) | 0.09 (0.14) | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.04 (0.14) | 0.07 (0.15) |

| Gender (0 = Male; 1 = non-Male) | 0.21 (0.14) | 0.16 (0.13) | 0.17 (0.13) | 0.15 (0.13) | 0.16 (0.13) |

| Individual Belief (0 = lean-multiculturalism; 1 = pro-multiculturalism) | 0.22 (0.12) | 0.21 (0.12) | 0.42 * (0.19) | 0.33 (0.19) | |

| District Support | 0.30 *** (0.05) | 0.37 *** (0.11) | |||

| School Support | 0.27 *** (0.06) | 0.31 ** (0.10) | |||

| Political Climate (0 = DEI-opposed; 1 = DEI-permissive) | 0.02 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.11 (0.13) | |

| Individual Belief * District Support | 0.29 (0.19) | ||||

| Individual Belief * Political Climate | −0.29 (0.24) | −0.20 (0.25) | |||

| District Support * Political Climate | −0.04 (0.14) | ||||

| Individual Belief * District Support * Political Climate | −0.60 * (0.23) | ||||

| Individual Belief * School Support | 0.29 (0.19) | ||||

| School Support * Political Climate | 0.03 (0.14) | ||||

| Individual Belief * School Support * Political Climate | −0.58 * (0.24) | ||||

| Individual Belief * District Support * Political Climate | −0.60 * (0.23) | ||||

| Individual Belief * School Support | 0.29 (0.19) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morman, K.M.; Wang, C.; Brady, L.M.; Fryberg, S.A. Individual and Contextual Morality: How Educators in Oppositional and Permissive Communities Use Culturally Responsive Practices. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040446

Morman KM, Wang C, Brady LM, Fryberg SA. Individual and Contextual Morality: How Educators in Oppositional and Permissive Communities Use Culturally Responsive Practices. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040446

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorman, Kate M., Cong Wang, Laura M. Brady, and Stephanie A. Fryberg. 2025. "Individual and Contextual Morality: How Educators in Oppositional and Permissive Communities Use Culturally Responsive Practices" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040446

APA StyleMorman, K. M., Wang, C., Brady, L. M., & Fryberg, S. A. (2025). Individual and Contextual Morality: How Educators in Oppositional and Permissive Communities Use Culturally Responsive Practices. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040446