Abstract

Trait Emotional Intelligence (Trait EI) is considered a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological well-being and may play a critical role in mitigating the risk of developing eating disorders (EDs), particularly in the context of pervasive social media use. However, the psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship, such as the driving factors of social media engagement, remain underexplored. This cross-sectional study aimed to examine whether motivating factors for social media use mediate the relationship between Trait EI and ED risk, as well as whether perceived social support moderates this relationship. A total of 388 Italian adolescents (Mage = 14.2; 50.7% girls) completed self-report questionnaires, including the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire—Adolescent Short Form (TEIQue-ASF), the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and the Motivations for Social Media Use Scale (MSMU). Data were collected between November 2023 and June 2024. Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 5). The results showed that lower Trait EI scores were significantly associated with higher EAT-26 scores (β = −11.03, p < 0.001). Motivation for social media use in terms of popularity, (β = −0.35, p < 0.05), appearance (β = −0.68, p < 0.01), and connection (β = −0.44, p < 0.05) significantly mediated this relationship. Perceived social support moderated this relationship in all models (β range = 0.08–0.10, p < 0.05), suggesting a buffering effect. The findings highlight the importance of Emotional Intelligence and social support as key psychological resources that may protect adolescents from disordered eating behaviors. Moreover, understanding the motivating factors behind social media use, particularly those centered on appearance and popularity, may help identify adolescents at greater risk and inform tailored prevention strategies.

1. Introduction

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a broad construct that refers to the ability to perceive, understand, regulate, and manage emotions in oneself and others. Within the EI framework, two primary conceptualizations have emerged: Trait EI and Ability EI (Petrides et al., 2016a; Mayer et al., 1999). Trait EI is defined as a set of emotion-related self-perceptions and dispositions, which are typically assessed through self-report measures and linked to personality traits (Pérez-González & Sanchez-Ruiz, 2014). Differently from Ability EI, which focuses on cognitive-affective processing and is measured through performance-based assessments, Trait EI captures stable emotional characteristics that shape how individuals experience and regulate their emotions in daily life (Siegling et al., 2015a).

A growing body of research suggests that Trait EI plays a crucial role in psychological well-being, acting as a protective factor against mental health disorders and maladaptive behaviors in adulthood (Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2016; Martins et al., 2010) and in adolescence (Gómez-Baya & Mendoza, 2018). More specifically, individuals with high Trait EI tend to employ adaptive emotional regulation strategies, which help them maintain positive emotional states and mitigate the impact of stressors (Andrei et al., 2022; Beath et al., 2015; Epifanio et al., 2023). Conversely, low Trait EI has been associated with higher vulnerability to mood disturbances, anxiety, and maladaptive coping mechanisms, including dysfunctional eating behaviors both in adults and adolescents (Biolcati et al., 2021; Cuesta-Zamora et al., 2018). Regarding this, given the well-established link between emotion regulation deficits and eating disorders (EDs) (Aldao et al., 2010), two recent systematic reviews further confirm this relationship, highlighting the negative association between Emotional Intelligence (EI) and various dimensions of EDs, emphasizing mechanisms such as adaptability, stress tolerance, and emotional regulation (Romero-Mesa et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022), and in this regard, Table 1 summarizes the differences between Ability EI and Trait EI, along with their relationships with EDs.

Table 1.

Overview of Trait and Ability EI in relation to EDs.

Going more in-depth, empirical evidence suggests that individuals with low EI may struggle with identifying and regulating negative emotions, which could increase the likelihood of engaging in disordered eating as a maladaptive coping strategy (Foye et al., 2019). Specifically, binge-eating episodes and restrictive eating behaviors have been linked to difficulties in processing emotions and reduced emotional self-efficacy (Romero-Mesa et al., 2020). Moreover, deficits in emotional processing can heighten susceptibility to external influences, including media-driven body image ideals and social comparison processes (Guerrini Usubini et al., 2024).

In recent years, the exponential growth in social media usage has raised concerns about its potential impact on adolescents’ mental health and eating behaviors. With approximately 60% of the global population actively engaged on social media platforms (Kemp, 2023), adolescents represent a particularly vulnerable population due to their ongoing identity formation and heightened sensitivity to social validation (Wartella et al., 2016; Prinstein et al., 2020). Research indicates that prolonged exposure to idealized body images on social media is associated with increased body dissatisfaction, self-esteem issues, and engagement in disordered eating behaviors, particularly among young females (Fardouly et al., 2020; Muzi et al., 2021).

However, while much of the existing literature focuses on the negative consequences of social media, recent studies highlight the importance of understanding the motivations behind adolescents’ engagement with these platforms. Rather than the mere duration of use, the underlying psychological factors driving social media consumption—such as the need for social approval and emotion regulation—may play a more significant role in shaping adolescents’ experiences and outcomes (Valkenburg et al., 2022). In this context, Trait EI may influence how adolescents interact with social media and whether their engagement fosters adaptive or maladaptive psychological outcomes (Vrinda et al., 2020).

Another key factor influencing adolescents’ emotional functioning is perceived social support (PSS), which has been consistently linked to improved well-being and lower risks of internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety (Cavanaugh & Buehler, 2016; Rueger et al., 2016). During adolescence, peer support and validation become particularly salient, and social media platforms serve as a primary medium for seeking feedback and connection (Crone & Konijn, 2018). While high PSS has been associated with greater emotional stability and life satisfaction (Jiménez-Iglesias et al., 2017), the absence of meaningful peer interactions online may exacerbate emotional distress and reinforce maladaptive behaviors, including disordered eating (Archer et al., 2019).

While prior research has examined the relationships between social media use, EDs, and Trait EI, there remains a significant gap in understanding the role of motivating factors for social media use and the nature of the content consumed. The current literature has primarily focused on quantitative aspects of social media engagement, such as screen time, rather than investigating the psychological drivers behind social media use and how they mediate the relationship between EI and ED risk.

The Present Study

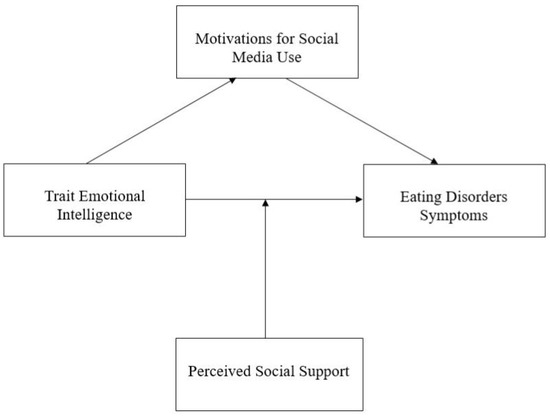

This cross-sectional study aims to examine the role of social media use motivation and perceived social support in the relationship between Trait EI and the risk of developing EDs. Specifically, we hypothesize that motivating factors for social media use act as mediators in this relationship. Individuals with low Trait EI may engage with social media for maladaptive reasons, such as seeking external validation or managing negative emotions, which in turn could increase their vulnerability to disordered eating behaviors. Additionally, we hypothesize that perceived social support acts as a moderator in this relationship (Figure 1). High levels of perceived social support may buffer against the negative effects of maladaptive social media use, thereby reducing the impact of low Trait EI on eating disorder risk. Conversely, low perceived social support may exacerbate emotional vulnerabilities, reinforcing the cycle of social media-driven body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors. By addressing these gaps, the present study seeks to advance our understanding of the theoretical relationships between Trait EI, social media motivations, and perceived social support. Ultimately, our findings aim to inform the development of targeted interventions that can reduce the risk of disordered eating behaviors in adolescents.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized mediation–moderation model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

The participants were adolescents from twelve classes, each from two Italian public secondary schools, both located in urban areas. The inclusion criteria required participants to be between the ages of 13 and 17 years and to have no prior diagnosis of eating disorders. The exclusion criteria included students with a history of eating disorders or those who did not provide parental consent. Permission for the study was first obtained from the school principals, followed by active signed consent from parents. The final sample comprised 388 adolescents, balanced between boys and girls (50.7% girls), with an average age of 14.2 years (SD = 0.72; age range = 13–15 years). An a priori power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1 indicated that a sample size of approximately 200 participants would be sufficient to detect a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.05) in a multiple regression model with three predictors at an alpha level of 0.05 and 80% statistical power. Given our sample size of 388 participants, the study had adequate power to detect small-to-moderate effects. Data collection took place between November 2023 and June 2024. Participants completed online anonymous self-report questionnaires during a regular school day in the presence of their teacher. Before data collection, they were reassured about confidentiality and informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The survey took approximately 30 min to complete. After completing the questionnaires, participants were thanked for their participation, and researchers addressed any questions raised. While public involvement was not directly included in the study design, school administrators and teachers were consulted throughout the research process, particularly in the recruitment phase and the facilitation of data collection within the schools.

All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2008). The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the institution of the first author (Prot. n.116/2022).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Risk of Eating Disorders

The Eating Attitude Test-26 (EAT-26; Garner et al., 1982; Dotti & Lazzari, 1998) in its Italian version was used to assess eating disorder symptoms. It consists of 26 items, scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from always to never. The questionnaire measures three primary dimensions: dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, and oral control. The total score ranges from 0 to 78, and a score equal to or higher than 20 indicates that a subject may be at risk of an eating disorder. Higher scores reflect more severe symptomatology. The EAT-26 has been widely applied to adolescent populations to identify early signs of disordered eating behaviors. Recent research confirms its reliability and validity in different cultural settings, and the reliability of this study was good: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85.

2.2.2. Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988) was used to assess perceived social support. This is a 12-item scale that measures perceived social support from three sources: Family, friends, and significant others. The scale was rated in a seven-point Likert response format (1 = “very strongly disagree” to 7 = “very strongly agree”). The total scores range from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater total perceived social support from all three sources. The internal reliability of the scale in our sample was good: Cronbach’ alpha = 0.89.

2.2.3. Trait Emotional Intelligence

The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire—Adolescent Short Form (TEIQue-ASF; Petrides et al., 2016b) was used for this study. We used the Italian version of the TEIQue for adolescents as the basis for our measure. Specifically, we derived the short-form version (TEIQue-ASF) by utilizing the Italian translation of the original short form. The translation was carefully reviewed and adapted for this study to ensure conceptual equivalence with the validated full version for Italian adolescents.

The Italian adaptation of the TEIQue for adolescents has been previously validated, demonstrating good psychometric properties and internal consistency (Andrei et al., 2014). This validation confirmed the appropriateness of the TEIQue framework for assessing Trait EI in Italian adolescents, supporting its relevance in research on emotional regulation, social interactions, and psychological well-being. The ASF comprises 30 short statements on a 7-point Likert scale designed to measure global Trait EI and the four broad factors of Trait EI: well-being, self-control, emotionality, and sociability. For the purpose of this study, only global Trait EI scores were used, and the questionnaire showed good internal reliability in our sample: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86.

2.2.4. Motivations for Social Media Use

The Motivations for Social Media Use Scale (MSMU; Rodgers et al., 2021) was used to assess motivations for social media use. This is a self-report questionnaire on a Likert scale designed to assess the psychological and behavioral motivations that drive individuals to engage with social media platforms (Rodgers et al., 2021). The scale identifies key motives underlying social media use, including social interaction, self-expression, entertainment, and information-seeking. The MSMU consists of multiple subscales, each measuring a distinct motivation for social media use, including “connection” (when social media is used to maintain relationships and interact with others), “popularity” (when social media is used for seeking social validation and online recognition), appearance (engaging with social media to compare and enhance physical self-presentation), and values and interests (using social media to explore personal interests and identity development). Since no validated Italian version of the MSMU currently exists, for this study, we back-translated the original English version into Italian. The reliability for this study ranges from acceptable to good for each subscale (connection = 0.63; popularity = 0.82; appearance = 0.84; values and interests = 0.71).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25. First, preliminary analyses, including Pearson’s correlation (r), were conducted to examine the relationships between Trait EI, motivation for the use of social media, perceived social support, and the risk of developing eating disorders. Additionally, multiple two-way ANOVAs were conducted to assess potential gender differences across these variables. Secondly, to examine the proposed mediation and moderation effects, we employed Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). Specifically, we tested a moderated mediation model (Model 5) in which Trait EI was input as the predictor variable, the risk of developing eating disorders as the outcome variable, and motivation for social media use as the mediator. Perceived social support was included as a moderator of the relationship between motivation for social media use and eating disorder risk. We conducted separate mediation and moderation analyses for each subscale of social media motivation to examine their distinct contributions to the model. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was utilized to generate confidence intervals for indirect effects, ensuring robustness in estimating mediation and moderation effects. The significance of effects was determined using 95% confidence intervals, where intervals not crossing zero indicated significant mediation or moderation effects.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Sex Differences

Descriptive statistics and sex differences for the study variables are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive information and sex differences in the sample.

Specifically, regarding screen time, the majority of adolescents (46.0%) reported spending between 3 and 5 h per day on social media. Additionally, 25.0% of participants spent 6 to 8 h daily. A smaller proportion, 10%, reported using social media for 9 to 11 h per day, while 4.9% of adolescents exceeded 12 h per day. In this regard, a significant sex difference was found, F = 24.21, p < 0.001, with males reporting lower screen time compared to females. For Trait EI, boys scored significantly higher than girls: F = 17.26, p < 0.001. In terms of perceived social support (PSS), both boys and girls reported comparable levels with no significant sex differences, F = 1.32, p > 0.05. Significant sex differences were observed in eating disorder risk, χ2 = 31.01, p < 0.001. A greater proportion of girls (32.3%) exceeded the clinical cut-off for eating disorder risk, compared to only 9.3% of males. Furthermore, among adolescents classified as at risk for EDs, the majority (47.6%) reported spending between 3 and 5 h online daily, while 25% reported 6 to 8 h, and 14.2% exceeded 12 h per day. Similarly, those who were not at risk predominantly reported mainly between 3 and 5 h per day (45.5%), with only 9.9% exceeding 12 h per day. With regard to motivation for social media use, girls reported significantly higher scores than males in the connection (F = 13.77, p < 0.001), popularity (F = 8.27, p < 0.01), and appearance (F = 12.77, p < 0.001) subscales, while no significant gender differences were found in the values and interest subscales (F = 0.42, p > 0.05).

3.2. Correlational Analysis

Bivariate associations between variables are reported in Table 3. Specifically, screen time showed a statistically significant positive correlation with eating disorder risk scores (r = 0.15, p = 0.003) and with some motivating factors for social media use, particularly connection (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), popularity (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), and appearance (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), while a significant negative association was found with Trait EI (r = −0.26, p < 0.001) and no significant association was found with perceived social support (r = −0.04, p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlational analysis between variables.

Trait EI global scores were negatively correlated with eating disorder risk (r = −0.38, p < 0.001) and with motivations for social media use, including connection (r = −0.29, p < 0.001), popularity (r = −0.18, p < 0.001), and appearance (r = −0.31, p < 0.001), while a positive association was found with perceived social support (r = 0.48, p < 0.001). Eating disorder risk scores were positively correlated with motivating factors for social media use, particularly appearance-based motivation (r = 0.27, p < 0.001), popularity motivation (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), and connection motivation (r = 0.22, p < 0.001), and negatively correlated with perceived social support (r = 0.15, p < 0.01) Finally, perceived social support was only negatively associated with appearance (r = −0.15, p = 0.003) among motivating factors for social media usage, while no association was found with other motivating factors (p > 0.05).

3.3. Mediation and Moderation Effects

With regard to the mediation effects of different motivating factors for social media use and the moderation effect of social support, for the relationship between Trait EI and ED risk, the results of each model are presented in Table 4. Specifically, in Model 1, the direct effect of Trait EI on eating disorder risk was significant (β = −10.92, SE = 3.05, p < 0.001), while the mediation analysis revealed that popularity motivation for social media use partially mediated the relationship (β = −0.35, SE = 0.15, p < 0.05) and perceived social support significantly moderated this relationship (β = 0.08, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05). In Model 2, which included appearance-based social media motivation, the direct effect of Trait EI on eating disorder risk remained significant (β = −11.03, SE = 3.05, p < 0.001). The mediation path through appearance motivation was significant (β = −0.68, SE = 0.22, p < 0.01), while perceived social support showed a small but significant moderation effect (β = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05). In Model 3, the same pattern was observed for connection motivation, where Trait EI negatively predicted eating disorder risk (β = −11.22, SE = 3.08, p < 0.001), and the mediation pathway through connection motivation was significant (β = −0.44, SE = 0.20, p < 0.05). Also, in this model, the moderation effect of perceived social support was significant (β = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05). In Model 4, which tested the motivation of interest/values for social media use as a mediator, the mediation path was not significant (β = 0.01, SE = 0.10, p > 0.05). However, the direct effect of Trait EI remained significant (β = −12.51, SE = 3.05, p < 0.001), while the moderation effect of perceived social support was also significant (β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05). Across all models, the total indirect effect of Trait EI on eating disorder risk through social media motivation and perceived social support was significant in the popularity, appearance, and connection models (p < 0.05) but not in the interest/values model (p > 0.05). The proportion of variance explained by the models (R2 values) ranged from 17% to 19%, indicating a moderate effect size.

Table 4.

Paths, effects, and confidence intervals of moderated–mediation models.

4. Discussion

The present study explored the relationships among Trait EI motivations for social media use, perceived social support, and adolescent ED risk. The preliminary findings largely align with the previous literature, particularly regarding sex differences in Trait Emotional Intelligence and eating disorder risk. However, certain results offer novel perspectives into the mediating role of social media motivation and the moderating effect of perceived social support. First of all, females reported higher levels of ED risk than males, supporting previous findings that showed that being an adolescent girl is associated with have more disordered eating behaviors, and this association could be explained by sociocultural pressures, body dissatisfaction, and engagement in appearance-driven social media use (Fardouly et al., 2020; Griffiths & Stefanovski, 2019). With regard to sex differences in Trait EI, our results showed that males scored higher in global Trait EI compared to females, which is in line with some prior research suggesting that boys may be better at regulating their own emotions, while girls could be better at recognizing and managing the emotions of others (Rafiee & Schacht, 2023). However, other studies challenge this perspective, indicating that gender differences in Trait EI are not always significant and may be context-dependent (Fischer et al., 2018). This inconsistency in the literature suggests that the relationship between sex and Emotional Intelligence is influenced by multiple factors, including socialization processes and the different kinds of measures used (Siegling et al., 2015b).

Our findings also highlight the significant association between screen time and eating disorder risk. This result is consistent with previous research linking excessive social media use with increased body dissatisfaction, social comparison, and engagement in maladaptive eating behaviors (Nesi, 2020). Moreover, our results showed a negative association between Trait EI and screen time, supporting the hypothesis that adolescents with lower Emotional Intelligence may use social media for longer, maybe as an external regulatory strategy for managing emotions (Calaresi et al., 2024). Individuals who struggle with emotional regulation or have difficulty mentalizing their emotions may be more inclined to engage in prolonged social media use as a form of emotional escape or a self-regulation mechanism using external devices.

The mediation and moderation models suggested, in general, that it is not just the amount of time spent on social media but rather the motivating factors underlying social media use that play a crucial role in explaining the relationship between Emotional Intelligence and eating disorder vulnerability. Specifically, Trait EI is negatively associated with specific motivations for social media use, particularly popularity and appearance, which in turn increase the risk of developing eating disorder symptoms. From this perspective, it is not surprising that motivations linked to physical appearance and the desire for social approval turned out to be factors mediating the relationship between Trait EI and the risk of eating disorders, whereas other motivations (such as values and interests) do not show a significant impact. This is in line with the notion that adolescents who engage with social media for self-presentation and social validation could be at a higher risk of disordered eating behaviors (Rodgers et al., 2020). Moreover, this aligns with prior studies suggesting that appearance-focused social media engagement fosters body dissatisfaction and maladaptive eating patterns (Vorobyeva & Nimchenko, 2022). The fact that popularity motivation also mediated this relationship could indicate that social comparison processes and peer validation pressures may further exacerbate disordered eating tendencies (Rodgers et al., 2020). Aiming to go more in-depth into these concepts, we can hypothesize that lower Trait EI predisposes adolescents to a reliance on social media as an external regulator of self-esteem, seeking likes, comments, or other forms of validation to compensate for difficulties in managing emotions and devaluated self-perception. Such reliance on external cues can exacerbate body dissatisfaction and self-comparison, both recognized as risk factors for disordered eating (Rodgers et al., 2020). Conversely, adolescents with higher Trait EI tend to regulate their emotions more autonomously and probably maintain a more stable sense of self-worth, thereby reducing their need for constant online approval. Moreover, the moderating role of perceived social support suggests that adolescents who feel supported by family, friends, or significant others may be less inclined to seek self-esteem boosts through social media, thus further protecting them from the risk of eating disorders. Specifically, higher levels of social support appeared to buffer the negative impact of low Emotional Intelligence, possibly promoting greater emotional resilience and reducing the need to seek validation through social media. Adolescents with strong perceived social support networks may be less likely to isolate themselves from real-world interactions, decreasing their reliance on social media as an external source of self-esteem enhancement, showing less dependence on virtual feedback, and benefiting from a “protective buffer” against the risk of internalizing unrealistic and harmful models proposed by social networks (Hidalgo-Fuentes & Fernández-Castilla, 2024).

In conclusion, these results may have many practical applications. Promoting Trait EI in adolescents (for instance, through emotional literacy training and programs aimed at enhancing socio-emotional skills) could reduce the need to seek external validation via social media constantly. Such an intervention, combined with the promotion of more awareness about the use of digital platforms, may help prevent the vicious cycle of social comparison and low self-esteem, reducing the risk of developing eating disorders. However, given the sample size limitations and the observed variability in effect estimates, these findings should be interpreted with caution and considered as preliminary evidence that requires further validation in larger-scale studies.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this research contributes to the advancement of the relationships between Trait EI, social media motivations, perceived social support, and eating disorder risk, several limitations should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow for definitive causal inferences regarding the observed associations, because different confounding variables could not be accounted for. Second, despite the fact that our sample size (N = 388) was adequate for detecting moderate effects, the variability in confidence intervals suggests that a larger sample could improve the precision and stability of the findings. Third, the use of only self-report measures raises the possibility of response bias, including social desirability and inaccuracies in recalling social media usage. Fourth, the sample was drawn from a specific cultural and geographical context, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Fifth, although screen time was considered, the study did not capture the more qualitative aspects of social media use (e.g., specific platforms, content types, or interaction patterns) that could further elucidate the mechanisms linking social media motivations to disordered eating. Finally, additional factors such as personality traits or peer influences, which may also shape adolescents’ online behaviors and vulnerability to eating disorders, were not included in the present analysis. Future research would benefit from employing longitudinal designs, incorporating more diverse samples, and examining a broader range of variables to deepen our understanding of these complex interrelationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.E. and M.R.; methodology, M.A.P. and M.R.; software, M.A.P.; validation, M.S.E., S.L.G. and C.N.; formal analysis, M.A.P.; investigation, M.R., M.A.P. and V.S.; resources, M.R. and S.L.G.; data curation, M.R. and M.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and M.A.P.; writing—review and editing, M.S.E., S.L.G. and M.A.P.; visualization, V.S. and C.N.; supervision, M.S.E. and S.L.G.; project administration, M.S.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethic Committee of University of Palermo (n. 116/2022, 16 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from both parents of each subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the school principals, teachers, parents and adolescents who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, F., Mancini, G., Agostini, F., Epifanio, M. S., Piombo, M. A., Riolo, M., Spicuzza, V., Neri, E., Lo Baido, R., La Grutta, S., & Trombini, E. (2022). Quality of life and job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mediation by hopelessness and moderation by trait emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, F., Mancini, G., Trombini, E., Baldaro, B., & Russo, P. M. (2014). Testing the incremental validity of trait emotional intelligence: Evidence from an Italian sample of adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, C. M., Jiang, X., Thurston, I. B., & Floyd, R. G. (2019). The differential effects of perceived social support on adolescent hope: Testing the moderating effects of age and gender. Child Indicators Research, 12(6), 2079–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beath, A. P., Jones, M. P., & Fitness, J. (2015). Predicting distress via emotion regulation and coping: Measurement variance in trait EI scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 84, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolcati, R., Mancini, G., Andrei, F., & Trombini, E. (2021). Trait emotional intelligence and eating problems in adults: Associations with alexithymia and substance use. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaresi, D., Cuzzocrea, F., Saladino, V., & Verrastro, V. (2024). The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and problematic social media use. Youth & Society, 57, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, A. M., & Buehler, C. (2016). Adolescent loneliness and social anxiety: The role of multiple sources of support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(2), 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E. A., & Konijn, E. A. (2018). Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nature Communications, 9(1), 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Zamora, C., González-Martí, I., & García-López, L. M. (2018). The role of trait emotional intelligence in body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms in preadolescents and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 126, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotti, A., & Lazzari, R. (1998). Validation and reliability of the Italian EAT-26. Eating and Weight Disorders—Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 3(4), 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epifanio, M. S., La Grutta, S., Piombo, M. A., Riolo, M., Spicuzza, V., Franco, M., Mancini, G., De Pascalis, L., Trombini, E., & Andrei, F. (2023). Hopelessness and burnout in Italian healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of trait emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1146408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., Rapee, R. M., Johnco, C. J., & Oar, E. L. (2020). The use of social media by Australian preadolescents and its links with mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(7), 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. H., Kret, M. E., & Broekens, J. (2018). Gender differences in emotion perception and self-reported emotional intelligence: A test of the emotion sensitivity hypothesis. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0190712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foye, U., Hazlett, D. E., & Irving, P. (2019). Exploring the role of emotional intelligence on disorder eating psychopathology. Eating and Weight Disorders—Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(2), 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12(4), 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Baya, D., & Mendoza, R. (2018). Trait emotional intelligence as a predictor of adaptive responses to positive and negative affect during adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S., & Stefanovski, A. (2019). Thinspiration and fitspiration in everyday life: An experience sampling study. Body Image, 30, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini Usubini, A., Bottacchi, M., Bondesan, A., Frigerio, F., Marazzi, N., Castelnuovo, G., & Sartorio, A. (2024). Emotional and behavioral impairment and comorbid eating disorder symptoms in adolescents with obesity: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(7), 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fuentes, S., & Fernández-Castilla, B. (2024). Problematic internet use and the big five personality model: An updated three-level meta-analysis. Behaviour & Information Technology, 43(14), 3537–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Camacho, I., Rivera, F., Moreno, C., & Matos, M. G. D. (2017). Social support from developmental contexts and adolescent substance use and well-being: A comparative study of spain and portugal. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20, E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, S. (2023). It’s a mean, mean world: Social media and mean world syndrome [Bachelor’s Thesis, Portland State University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review, 8(4), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzi, S., Sansò, A., & Pace, C. S. (2021). What’s happened to Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic? A preliminary study on symptoms, problematic social media usage, and attachment: Relationships and differences with pre-pandemic peers. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 590543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J. (2020). The impact of social media on youth mental health: Challenges and opportunities. North Carolina Medical Journal, 81(2), 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J., Furnham, A., & Pérez-González, J.-C. (2016a). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emotion Review, 8(4), 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., Siegling, A. B., & Saklofske, D. H. (2016b). Theory and measurement of trait emotional intelligence. In The Wiley handbook of personality assessment (pp. 90–103). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, J. C., & Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J. (2014). Trait emotional intelligence anchored within the big five, big two and big one frameworks. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M. J., Nesi, J., & Telzer, E. H. (2020). Commentary: An updated agenda for the study of digital media use and adolescent development—Future directions following Odgers & Jensen (2020). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, Y., & Schacht, A. (2023). Sex differences in emotion recognition: Investigating the moderating effects of stimulus features. Cognition and Emotion, 37, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R. F., Mclean, S. A., Gordon, C. S., Slater, A., Marques, M. D., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Development and validation of the motivations for social media use scale (MSMU) among adolescents. Adolescent Research Review, 6(4), 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R. F., Slater, A., Gordon, C. S., McLean, S. A., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2020). A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Mesa, J., Pelaez-Fernandez, M. A., & Extremera, N. (2020). Emotional intelligence and eating disorders: A systematic review. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegling, A. B., Furnham, A., & Petrides, K. V. (2015a). Trait emotional intelligence and personality: Gender-invariant linkages across different measures of the big five. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(1), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegling, A. B., Petrides, K. V., & Martskvishvili, K. (2015b). An examination of a new psychometric method for optimizing multi–faceted assessment instruments in the context of trait emotional intelligence. European Journal of Personality, 29(1), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P. M., Meier, A., & Beyens, I. (2022). Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyeva, E., & Nimchenko, A. (2022). Cognitive and personality traits of social media users with eating disorders. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education (IJCRSEE), 10(3), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrinda, Madaan, R., Bhatia, K. K., & Bhatia, S. (2020, January 29–31). Understanding the role of emotional intelligence in usage of social media. 2020 10th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence) (pp. 586–591), Noida, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartella, E., Rideout, V., Montague, H., Beaudoin-Ryan, L., & Lauricella, A. (2016). Teens, health and technology: A national survey. Media and Communication, 4(3), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Wu, C., & He, J. (2022). The relationship between emotional intelligence and eating disorders or disordered eating behaviors: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).