Analyzing Teacher–Student Verbal Interaction in Elementary Chinese Comprehensive Class: Insights from Flanders Interaction Analysis System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How does teachers’ behavior influence the cultural–linguistic backgrounds of elementary CFL learners’ autonomous participation?

- (2)

- What verbal interaction patterns occur in multicultural CFL classrooms?

- (3)

- What are the illuminations for enhancing the classroom teaching of novice Chinese language teachers?

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Research Design

2.4. Classroom Observation and Data Recording

2.5. Construction of the Analysis Matrix

3. Results

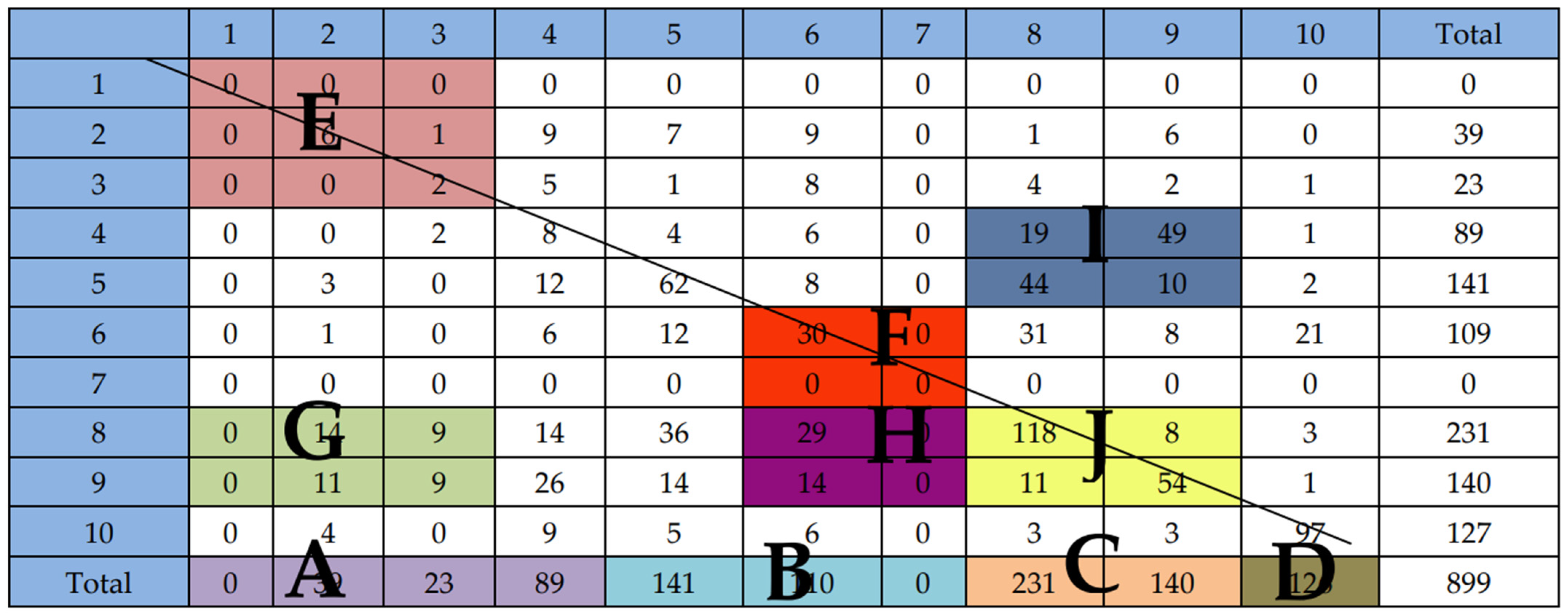

3.1. Matrix Analysis

3.2. Ratio Analysis

3.2.1. Analysis of Classroom Structure

3.2.2. Analysis of Teaching Tendencies

Control Type Analysis

Analysis of Reinforcement Types

3.2.3. Feature Sequence Pair Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Teacher’s Verbal Behavior

4.2. Features of Students’ Verbal Behavior

4.3. Principles of Classroom Teaching

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Recommendations for Novice Teachers

5.2. Implications for Curriculum Development and Teacher Training

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Binmohsen, S. A., & Abrahams, I. (2020). Science teachers’ continuing professional development: Online vs face-to-face. Science & Technological Education, 40(3), 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S., Niu, X., Wen, Y., & Li, J. (2021). Interaction analysis of teachers and students in inquiry class learning based on augmented reality by iFIAS and LSA. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(9), 5551–5567. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T. P. (2013). Codeswitching and participant orientations in a Chinese as a foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 869–886. [Google Scholar]

- Claramita, M., Nurokhmanti, H., Qomariyah, N., Budiastuti, V. I., Utomo, P. S., & Findyartini, A. (2022). Facilitating student-cantered learning: In the context of social hierarchies and collectivistic culture. In Challenges and opportunities in health professions education: Perspectives in the context of cultural diversity (pp. 17–43). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders, N. A. (1961). Analyzing teacher behavior. Educational Leadership, 19, 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders, N. A. (1963). Intent, action and feedback: A preparation for teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 14(3), 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, H. J. (1981). Three decades of the Flanders interaction analysis system. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 16(2), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W. (2009). Research on the interaction between teachers and students’ speech acts in classroom teaching. Educational Research and Experiment, 5, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z. H. (2018). Task-based learning in task-based teaching: Training teachers of Chinese as a foreign language. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 38, 162–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. Y., Fan, X. T., Jennifer, L., Chen, L., & Yang, N. (2016). Profiles of teacher-child interactions in Chinese kindergarten classrooms and the associated teacher and program features. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. H., & Zhu, N. (2019). On the speech act interactions between teachers and students in Chinese language and literature classrooms of schools for hearing-impaired students-based on the Flanders Interactive Analysis System (FIAS). Chinese Journal of Special Education, 3, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P. (2020). The application of flipped classroom teaching mode in international Chinese teaching. In 5th International Symposium on Social Science (Vol. 3, pp. 169–173). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., Kim, T. E., & Park, J. (2024). The cognitive construction-grammar approach to teaching the Chinese Ba construction in a foreign language classroom. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 62(2), 457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S. Y. (2020). A comparative study of classroom teaching language between math expert teachers and ordinary teachers in the junior middle school [Master’s thesis, Anshan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. (2016). The application of Flanders Interaction Analysis System in teaching Chinese as a second language in the classroom---Take the tourism Chinese lesson of Dungan as an example [Master’s thesis, Northwest Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. S. (2019). A study on classroom interaction of novice teachers’ elementary integrated classes based on Flanders interaction analysis system [Master’s thesis, Shandong Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y. L. (2004). The research on classroom teaching of Chinese as a second language. Chinese Teaching in the World, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, S., & Ke, C. R. (1992). Using authentic cultural materials to teach reading in Chinese. Foreign Language Annals, 25(3), 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, H., & Wu, J. H. (2003). Establishment of links between quantitative structure and meaning comprehension. Educational Research, 5, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nunan, D. (2012). Learner-centered English language education: The selected works of David Nunan. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J. (2024). Analyzing the time-series relationship between learning atmosphere, negative emotions, and academic engagement in language learners. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K. L. (2022). The balanced school day and teacher-student connections: Canadian classroom teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Learning and Teaching (IJLT), 8(4), 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Reznitskaya, A., & Maughn, G. (2013). Student thought and classroom language: Examining the mechanisms of change in dialogic teaching. Educational Psychologist, 48(2), 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J. C. (2005). Communicative language teaching today. SEAMEO Regional Language Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Riyadini, M. V., & Basikin, B. (2024). Analyzing patterns of classroom interaction in an elementary english online teaching and learning processes. The Journal of English Teaching for Young and Adult Learners, 3(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, V. D. (2009). An analysis of teacher and student interactions in desegregated school environments [Ph.D. thesis, Arkansas State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Septiningtyas, M. (2016). A study of interaction in teaching English to young learners (TEYL) classroom using Flanders’ interaction analysis system. Sanata Dharma University. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. B., Ward, G., & Rosenshein, J. S. (1977). Improving instruction by measuring teacher discussion skills. American Journal of Physics, 45(1), 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, M., & Yamazaki, Y. (2021). Classroom interventions and foreign language anxiety: A systematic review with narrative approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T. M., & Ren, Z. (2015). A summary of the comparative research on novice, proficient, and expert TCSOL teachers. Journal of Yunnan Normal University (Teaching and Research on Chinese as a Foreign Language), 2015(13), 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. (2022). Research on tone errors and correction in Chinese-as-a-Second-Language teaching. Applied Linguistics, 2, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, M., & Sharkey, S. (2003). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. Teaching Sociology, 31(2), 251. [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn, J. J. (1968). Chinese language teaching in the United States: The state of the art. Educational Resources Information Center. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. Y., & Yan, J. (2010). The research of teacher and student’s speech interaction in chemical teaching. Journal of Schooling Studies, 1, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. P., & Zhang, J. M. (2018). Analysis of chemistry classroom language behavior characteristics based on excellent lessons. Chinese Journal of Chemical Education, 13, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. (2014). The technique and features of Flanders interaction analysis system. Contemporary Education and Culture, 2, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. (2018). The research on classroom teaching of oral Chinese as a foreign language. In 2nd international conference on culture, education and economic development of modern society (pp. 193–196). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X. L., & Liu, Y. (2015). An exploration on the analysis path of teacher-student discourse misunderstanding in teaching Chinese as a foreign language. Journal of Higher Education, 16, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Code | Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher language | Indirect Impact | 1 | Acceptance of emotions |

| 2 | Encouragement or praise | ||

| 3 | Accepting or using students’ perspectives | ||

| 4 | Asking a question | ||

| Direct Impact | 5 | Lecture | |

| 6 | Giving guidance or instructions | ||

| 7 | Criticizing or asserting authority | ||

| Student language | 8 | Students speaking passively | |

| 9 | Student-initiated speech | ||

| Silence or confusion | 10 | Invalid language | |

| Seconds | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 9 | |

| 4 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 6 | |

| 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 9 | |

| 6 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 5 | |

| 7 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | |

| 8 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | |

| 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | |

| 10 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| 11 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | |

| 12 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 10 | |

| 13 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 14 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | |

| 15 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | |

| 16 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 8 | |

| 17 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | |

| 18 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

| 19 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 4 | |

| 20 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| 21 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 10 | |

| 22 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | |

| 23 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 9 | |

| 24 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 25 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 26 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| 27 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 28 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 8 | |

| 29 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | |

| 30 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |

| 31 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 32 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| 33 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 34 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | |

| 35 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 10 | |

| 36 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 37 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 38 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 9 | |

| 39 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 10 | |

| 40 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 41 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 42 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | |

| 43 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 44 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 2 | |

| 45 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 39 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 23 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 19 | 49 | 1 | 89 |

| 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 62 | 8 | 0 | 44 | 10 | 2 | 141 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 30 | 0 | 31 | 8 | 21 | 109 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 36 | 29 | 0 | 118 | 8 | 3 | 231 |

| 9 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 26 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 11 | 54 | 1 | 140 |

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 97 | 127 |

| Total | 0 | 39 | 23 | 89 | 141 | 110 | 0 | 231 | 140 | 126 | 899 |

| Category | Number of Occurrences | Ratio | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Language | 402 | 44.72% | 20.1 min |

| Student Language | 371 | 41.27% | 18.6 min |

| Invalid Language | 126 | 14.01% | 6.3 min |

| Class Type | Code | Projects | Number of Occurrences | Ratio | Indirect Language/ Direct Language | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Impact | 1 | Acceptance of students’ emotions | 0 | 0 | 37.57% | 60.18% |

| 2 | Expressing emotions to praise students | 39 | 9.71% | |||

| 3 | Accepting or using the student’s claim | 23 | 5.72% | |||

| 4 | Asking a question | 89 | 22.14% | |||

| Direct Impact | 5 | Lecture | 141 | 35.07% | 62.43% | |

| 6 | Giving guidance or instructions | 110 | 27.36% | |||

| 7 | Criticizing students or asserting authority | 0 | 0 | |||

| Category | Positive Reinforcement (Columns 1–3) | Negative Reinforcement (Columns 6–7) | Positive Reinforcement/ Negative Reinforcement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of times | 62 | 110 | 56.36% |

| Category | (4, 4) | (4, 8) | (8, 4) | (8, 8) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 8 | 19 | 14 | 118 | 159 |

| Ratio | 0.89% | 2.11% | 1.56% | 13.13% | 17.69% |

| Category | (3, 3) | (3, 9) | (9, 3) | (9, 9) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 2 | 2 | 9 | 54 | 67 |

| Ratio | 0.22% | 0.22% | 1.00% | 6.01% | 7.45% |

| Category | (4, 4) | (4, 9) | (9, 4) | (9, 9) | Total |

| Frequency | 8 | 49 | 26 | 54 | 137 |

| Ratio | 0.89% | 5.45% | 2.89% | 6.01% | 15.24% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Yang, W.; Guo, Y. Analyzing Teacher–Student Verbal Interaction in Elementary Chinese Comprehensive Class: Insights from Flanders Interaction Analysis System. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040429

Guo X, Yang W, Guo Y. Analyzing Teacher–Student Verbal Interaction in Elementary Chinese Comprehensive Class: Insights from Flanders Interaction Analysis System. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040429

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xingrong, Wensi Yang, and Yiming Guo. 2025. "Analyzing Teacher–Student Verbal Interaction in Elementary Chinese Comprehensive Class: Insights from Flanders Interaction Analysis System" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040429

APA StyleGuo, X., Yang, W., & Guo, Y. (2025). Analyzing Teacher–Student Verbal Interaction in Elementary Chinese Comprehensive Class: Insights from Flanders Interaction Analysis System. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040429