Psychometric Evaluation of the Performance Perfectionism Scale for Sport in the South Korean Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Measures of Perfectionism

1.2. Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Translation Process

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Perfectionism Scale for Sport

2.3.2. Perceived Stress

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

3. Result

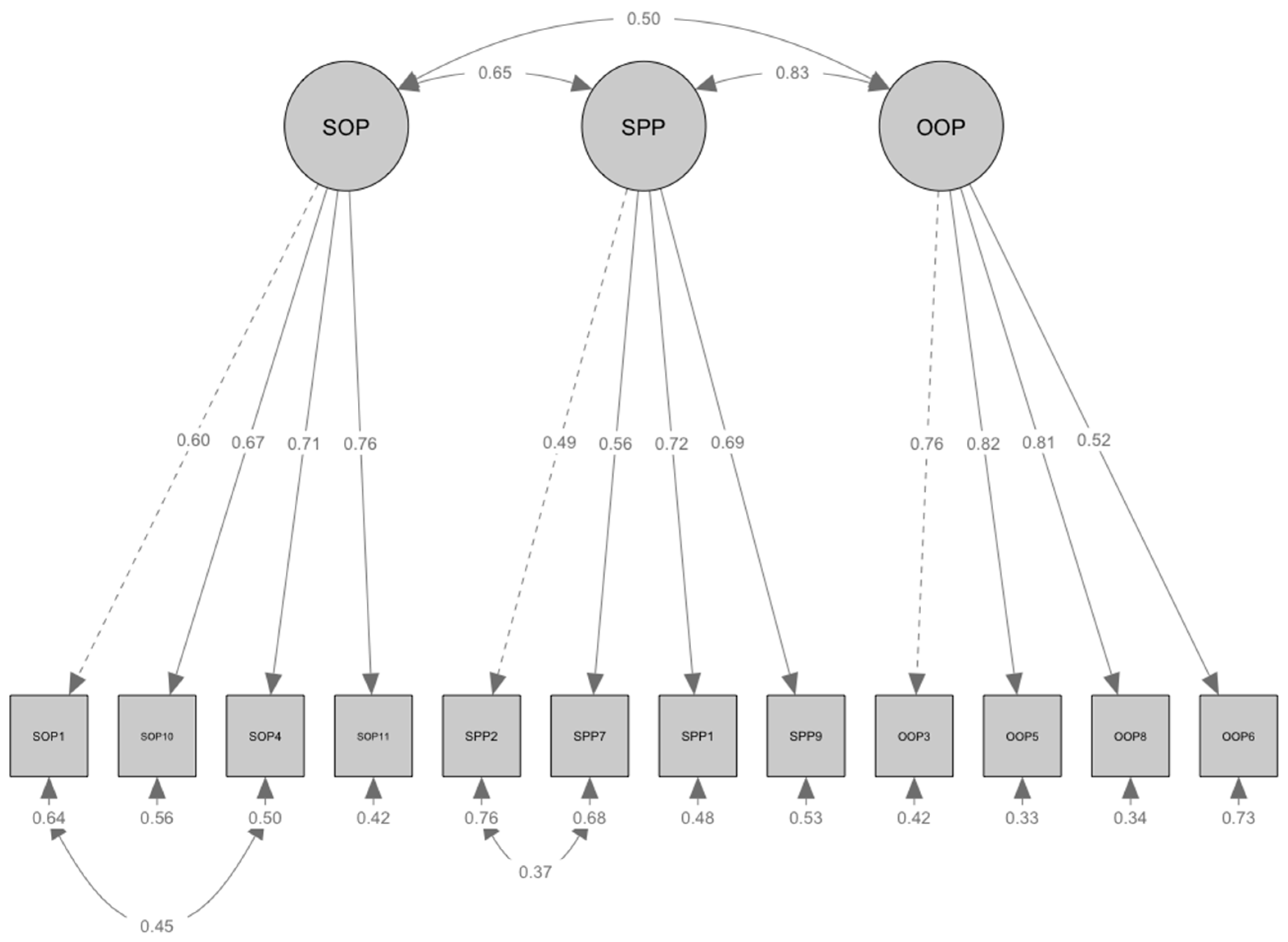

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Convergent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Strength and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angelo, D. L., Neves, A. N., Correa, M., Sermarine, M., Zanetti, M. C., & Brandão, M. R. F. (2019). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de perfeccionismo en el deporte (PPS-S) para el contexto brasileño. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 19(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D. L., & Finney, S. J. (2018). Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D. D. (1980). The perfectionist’s script for self-defeat. Psychology Today, 14(6), 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J. G. H., Gotwals, J. K., & Dunn, J. C. (2005). An examination of the domain specificity of perfectionism among intercollegiate student-athletes. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(6), 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, S. J., Piek, J. P., Dyck, M. J., & Rees, C. S. (2007). The role of dichotomous thinking and rigidity in perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(8), 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esentaş, M., Güzel, P., & Tez, Ö. Y. (2020). Sporda mükemmel performans ölçeği’nin (PPS-S) çocuk ve yetişkin sporcular için geçerlik ve güvenirliğinin incelenmesi: Kısa form. Ulusal Spor Bilimleri Dergisi, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2005). The perils of perfectionism in sports and exercise. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(1), 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotwals, J. K., & Dunn, J. G. H. (2009). A multi-method multi-analytic approach to establishing internal construct validity evidence: The sport multidimensional perfectionism scale 2. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 13(2), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A. P., Appleton, P. R., & Mallinson, S. H. (2016). Development and initial validation of the performance perfectionism scale for sport (PPS-S). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. P., Mallinson-Howard, S. H., & Jowett, G. E. (2018). Multidimensional perfectionism in sport: A meta-analytical review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(3), 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. S., Lee, J. W., Phillips, L. R., Zhang, X. E., & Jaceldo, K. B. (2001). An Adaptation of brislin’s translation model for cross-cultural research. Nursing Research, 50(5), 300. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.-J., Cheon, S.-M., & Park, J.-H. (2020). A mixed approach to psychological skills training: Integrating team lecture and individual consulting. Korean Society of Sport Psychology, 31(4), 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.-S. (2021). Sports mental coaching bible. The Road. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H., & Park, J.-S. (2019). The effects of multidimensional perfectionism of taekwondo demonstration members on their excercise adherence and satisfaction. Taekwondo Journal of Kukkiwon, 10(3), 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-M., & Cho, S.-L. (2023). Verifying the role of stress in the relationship between perfectionism and athlete exhaustion in youth athletes. Korean Journal of Sports Science, 32(2), 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K., & Oh, H.-O. (2008). The relationship between exercise affects and perfectionism in participants of Leisure sports. The Korean Journal of Physical Education, 47(6), 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y. (2020). Being a student-athlete in college—The experiences of balancing academics and sports. The Korean Association of General Education, 14(2), 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Han, M., & Lee, J.-H. (2021). Sport and exercise psychology in Korea: Three decades of growth. Asian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, H. (2023). The effect of internalized shame on multidimensional perfectionism and self-control in college athletes. Korean Journal of Sport Psychology, 34(4), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Sport & Olympic Committee. (2024). Sport support portal—Registration status. Available online: https://g1.sports.or.kr/stat/stat02.do (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Kwon, W., & Cho, S. K. (2020). Associations among perfectionism, anxiety, and psychological well-being/ill-being in college athletes of South Korea. International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, 32(2), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-H. (2024). An analysis of the mediating effects of mindset and grit in the relationship between perfectionism and positive psychological capital of participants in marine leisure sports. The Korea Journal of Sport, 22(3), 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, D. J. (2023). Advances in the measurement of perfectionism in sport, dance, and exercise. In The Psychology of perfectionism in sport, dance, and exercise (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, J., Velghe, J., Fee, J., Isserow, S., & Drezner, J. A. (2019). Defining athletes and exercisers. The American Journal of Cardiology, 123(3), 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B. H., Hong, D., Marshall, R. C., & Hong, J. H. (2018). Rethinking social activism regarding human rights for student-athletes in South Korea. Sport in Society, 21(11), 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L. F., Madigan, D. J., Hill, A. P., & Grugan, M. C. (2022). Do athlete and coach performance perfectionism predict athlete burnout? European Journal of Sport Science, 22(7), 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Seo, Y. S. (2010). Validation of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) on samples of korean university students. Korean Journal of Psychology: General, 29(3), 611–629. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, B. J. I., Gaudreau, P., & Rose, L. (2025). Practically perfect in every way: Perfectionism and evaluations of perfect performances in sport. Personality and Individual Differences, 234, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y., & Kim, M. (2022). The relationship of perceived pressure, perfectionism and burnout among ice hockey players. The Korean Journal of Physical Education, 61(4), 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.-B., Kim, Y.-K., & Kang, Y.-G. (2024). The meaning of acceptance of perfectionism as perceived on KLPGA players. The Korean Journal of Sport, 22(1), 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J., Otto, K., & Stoll, O. (2006, November). Multidimensional Inventory of Perfectionism in Sport (MIPS): English version [Other]. School of Psychology, University of Kent. Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/41560/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Yang, J.-H., Yang, H.-J., Choi, C., & Bum, C.-H. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis on burnout owing to perfectionism in elite athletes based on the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) and Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ). Healthcare, 11(10), 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y., & Masuda, T. (2024). Cultural variation in self-assessment in athletes: Towards the development of culturally-grounded approach in sports psychology. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.-K., & Cho, S.-L. (2024). A single-case study on a psychological skills training program to prevent dropout among track and field student athletes. Korean Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1(2), 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Dimension | English | Korean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SOP | I am tough on myself when I do not perform perfectly. | 내가 완벽하게 수행하지 못할 때, 나는 나 자신에게 가혹하다. |

| 4 | SOP | I put pressure on myself to perform perfectly. | 나는 완벽하게 수행하기 위해 스스로에게 압박을 준다. |

| 10 | SOP | I only think positively about myself when I perform perfectly. | 나는 완벽하게 수행할 때만 나 자신에 대해 긍정적으로 생각한다. |

| 11 | SOP | To achieve the standards I have for myself, I need to perform perfectly. | 내가 정한 기준에 도달하기 위해 나는 완벽하게 수행해야 한다. |

| 2 | SPP | People always expect more, no matter how well I perform. | 내가 아무리 좋은 퍼포먼스를 보여도 사람들은 항상 더 높은 기대를 한다. |

| 7 | SPP | People always expect my performances to be perfect. | 사람들은 항상 내가 완벽하게 수행하길 기대한다. |

| 9 | SPP | People view even my best performances negatively. | 사람들은 내 최선의 퍼포먼스도 부정적으로 본다. |

| 12 | SPP | People criticize me if I do not perform perfectly. | 내가 완벽하게 수행하지 않으면 사람들은 나를 비판한다. |

| 3 | OPP | I have a lower opinion of others when they do not perform perfectly. | 다른 사람들이 완벽하게 수행하지 않으면 나는 그들에 대해 낮게 평가한다. |

| 6 | OPP | I am never satisfied with the performances of others. | 나는 다른 사람들의 퍼포먼스에 절대 만족하지 않는다. |

| 8 | OPP | I criticize people if they do not perform perfectly. | 사람들이 완벽하게 수행하지 않으면 나는 그들을 비판한다. |

| 5 | OPP | I think negatively of people when they do not perform perfectly. | 사람들이 완벽하게 수행하지 않으면 나는 그들에 대해 부정적으로 생각한다. |

| Item | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOP1 | 3.27 | 1.004 | −0.348 | −0.342 |

| SPP2 | 3.10 | 0.964 | 0.146 | −0.380 |

| OOP3 | 2.50 | 0.988 | 0.292 | −0.476 |

| SOP4 | 3.28 | 1.050 | −0.312 | −0.531 |

| OOP5 | 2.26 | 0.983 | 0.460 | −0.525 |

| OOP6 | 2.59 | 1.055 | 0.366 | −0.524 |

| SPP7 | 3.01 | 1.013 | −0.112 | −0.526 |

| OOP8 | 2.09 | 0.914 | 0.686 | 0.104 |

| SPP9 | 2.19 | 0.998 | 0.633 | −0.235 |

| SOP10 | 3.00 | 1.176 | 0.000 | −0.903 |

| SOP11 | 3.47 | 1.052 | −0.507 | −0.182 |

| SPP12 | 2.36 | 1.017 | 0.545 | −0.252 |

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 264 (79.5) |

| Female | 68 (20.5) |

| Academic Year | |

| Freshman | 116 (34.9) |

| Sophomore | 125 (37.7) |

| Junior | 72 (21.7) |

| Senior | 19 (5.7) |

| National Team Status 1 | |

| No National Team Experience | 244 (73.5) |

| Previous Experience with the National Team | 80 (24.1) |

| Current National Team Member | 8 (2.4) |

| Sport Type | |

| Taekwondo 2 | 116 (34.9) |

| Soccer | 61 (18.4) |

| Basketball | 26 (7.8) |

| Baseball | 25 (7.5) |

| Rugby | 21 (6.3) |

| Bowling | 12 (3.6) |

| Handball | 11 (3.3) |

| Ice Hockey | 10 (3.0) |

| Volleyball | 9 (2.7) |

| Horseback Riding | 9 (2.7) |

| Gymnastics | 9 (2.7) |

| Ssireum 3 | 8 (2.4) |

| Archery | 8 (2.4) |

| Kendo | 2 (0.6) |

| Skiing | 2 (0.6) |

| Badminton | 1 (0.3) |

| Aerobics | 1 (0.3) |

| Jiu-jitsu | 1 (0.3) |

| Variable | SOP | SPP | OOP | Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOP | 3.25 | |||

| SPP | 0.55 | 2.67 | ||

| OOP | 0.44 | 0.62 | 2.36 | |

| Stress | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 3.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, Y.; Ko, H.; Kim, B. Psychometric Evaluation of the Performance Perfectionism Scale for Sport in the South Korean Context. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040424

Seo Y, Ko H, Kim B. Psychometric Evaluation of the Performance Perfectionism Scale for Sport in the South Korean Context. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040424

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Yeongjun, Hwasup Ko, and Bumsoo Kim. 2025. "Psychometric Evaluation of the Performance Perfectionism Scale for Sport in the South Korean Context" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040424

APA StyleSeo, Y., Ko, H., & Kim, B. (2025). Psychometric Evaluation of the Performance Perfectionism Scale for Sport in the South Korean Context. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040424