COVID-19 Induced Stigmas of Imported Cold-Chain Food Among Chinese Consumers: Multi-Round Tracking Surveys

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Econometric Model

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

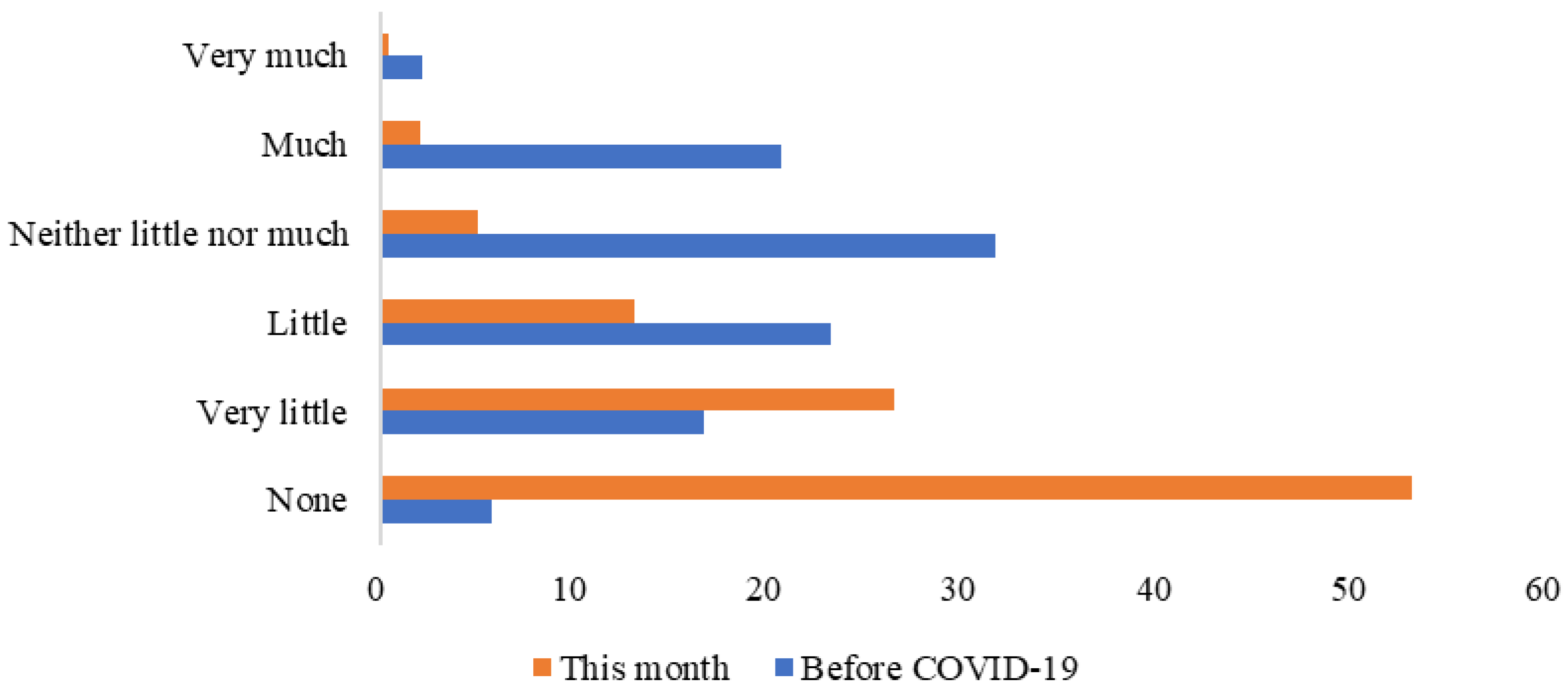

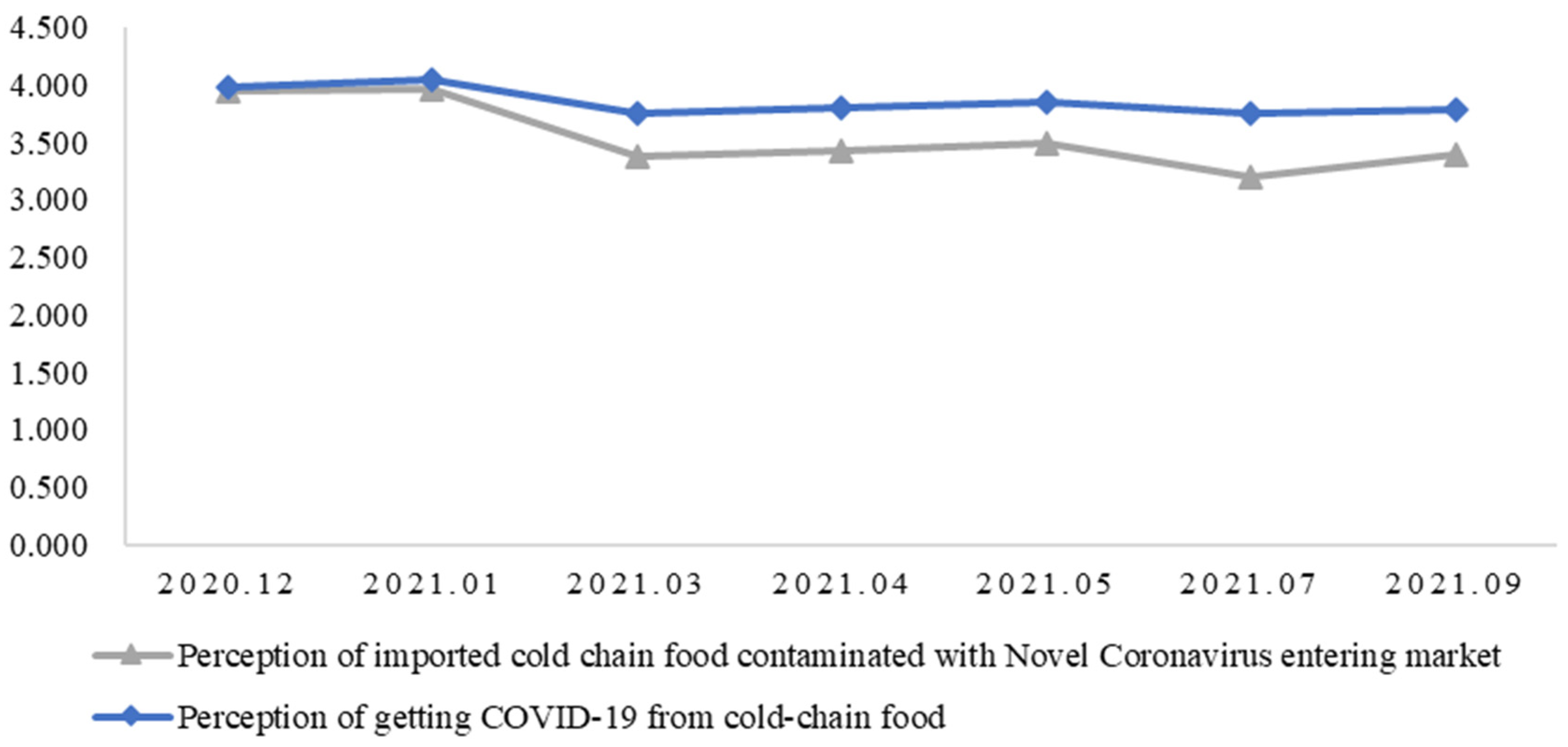

3.2. Respondents’ Risk Perception of Cold-Chain Beef

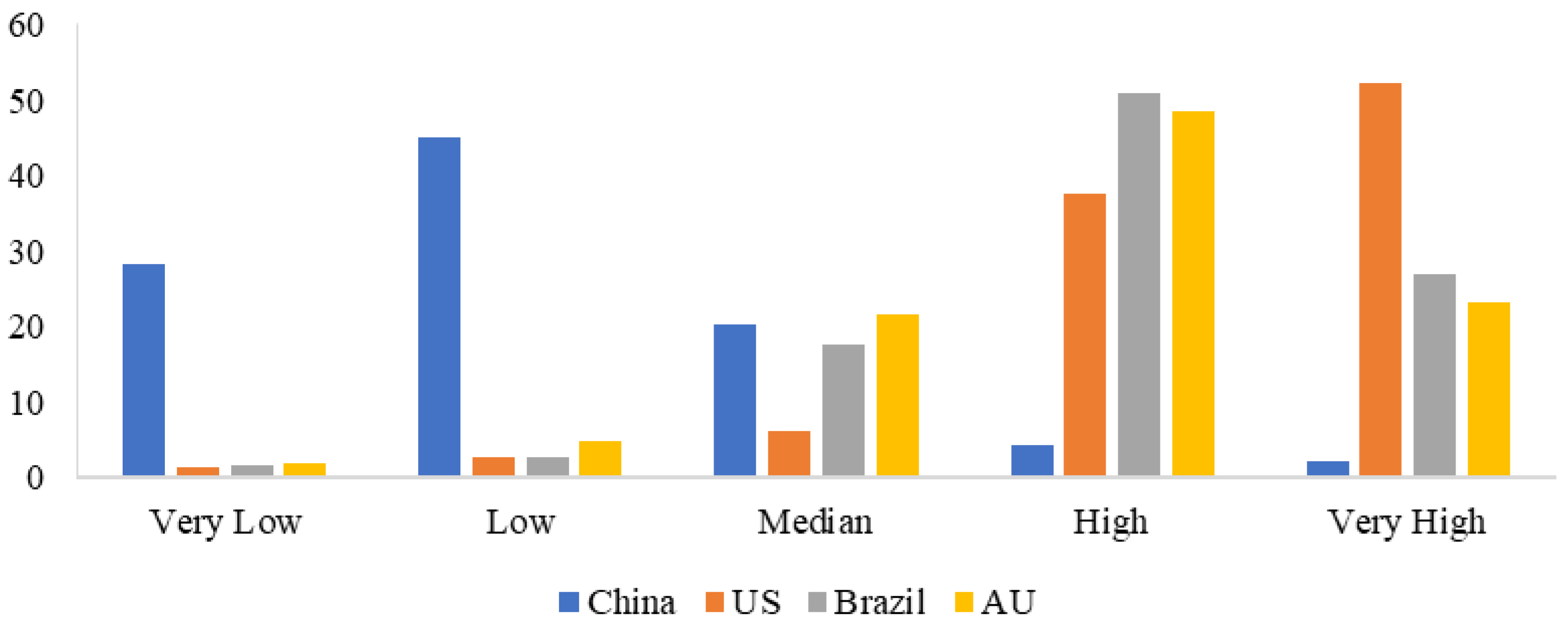

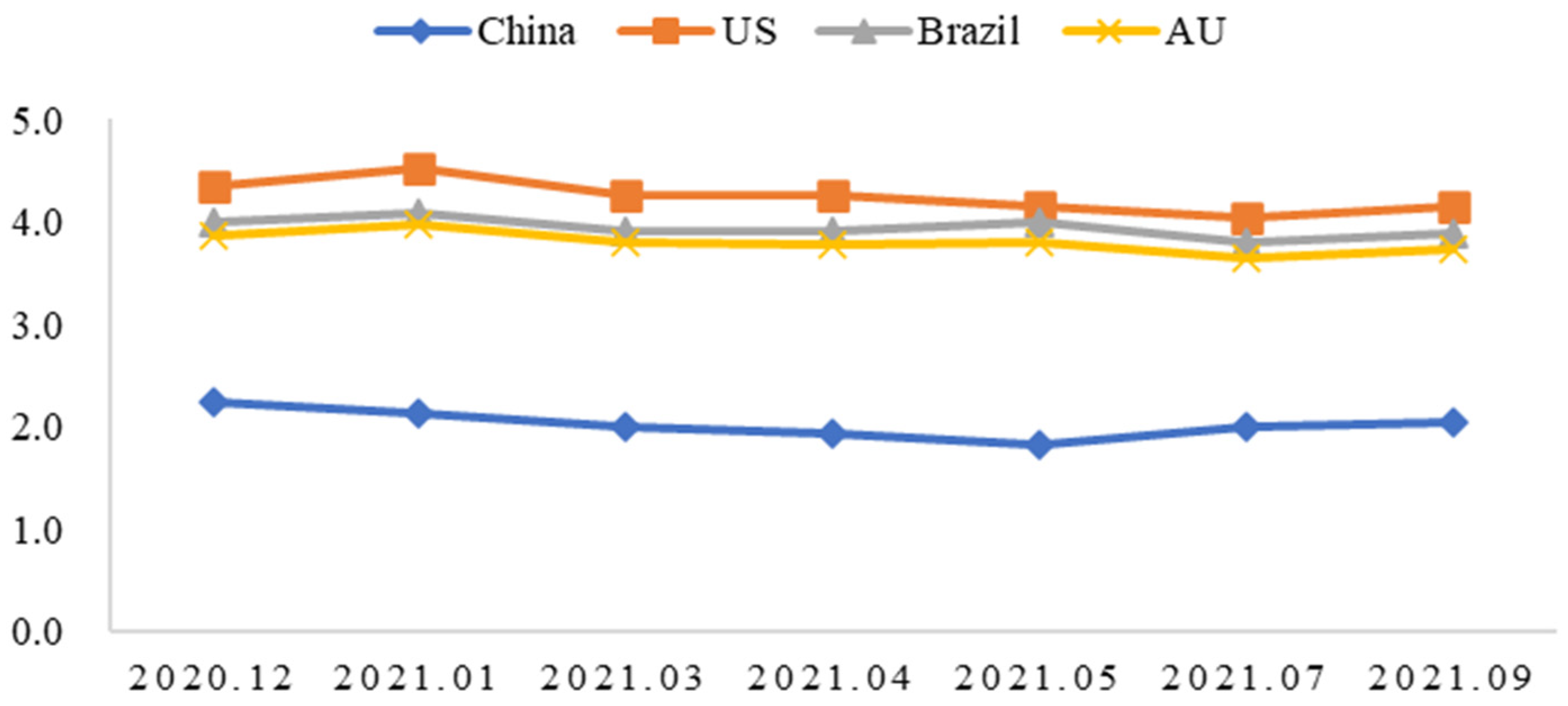

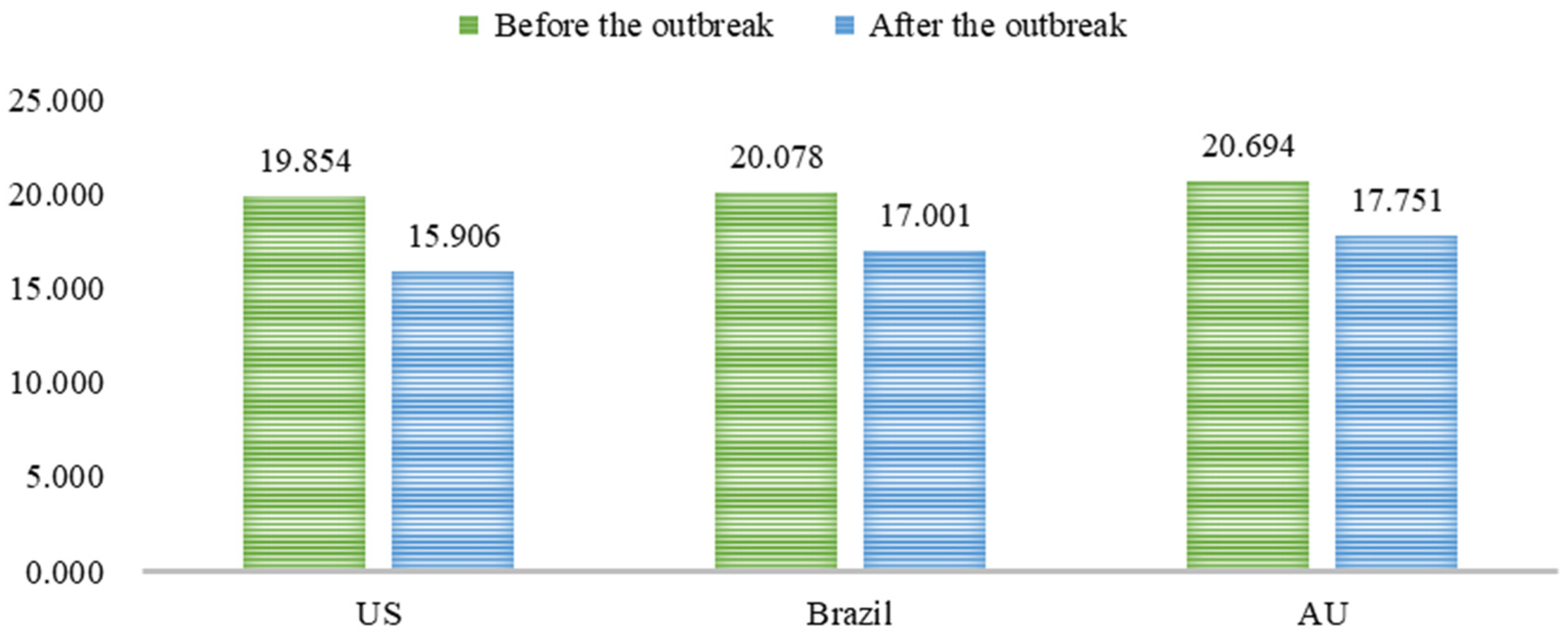

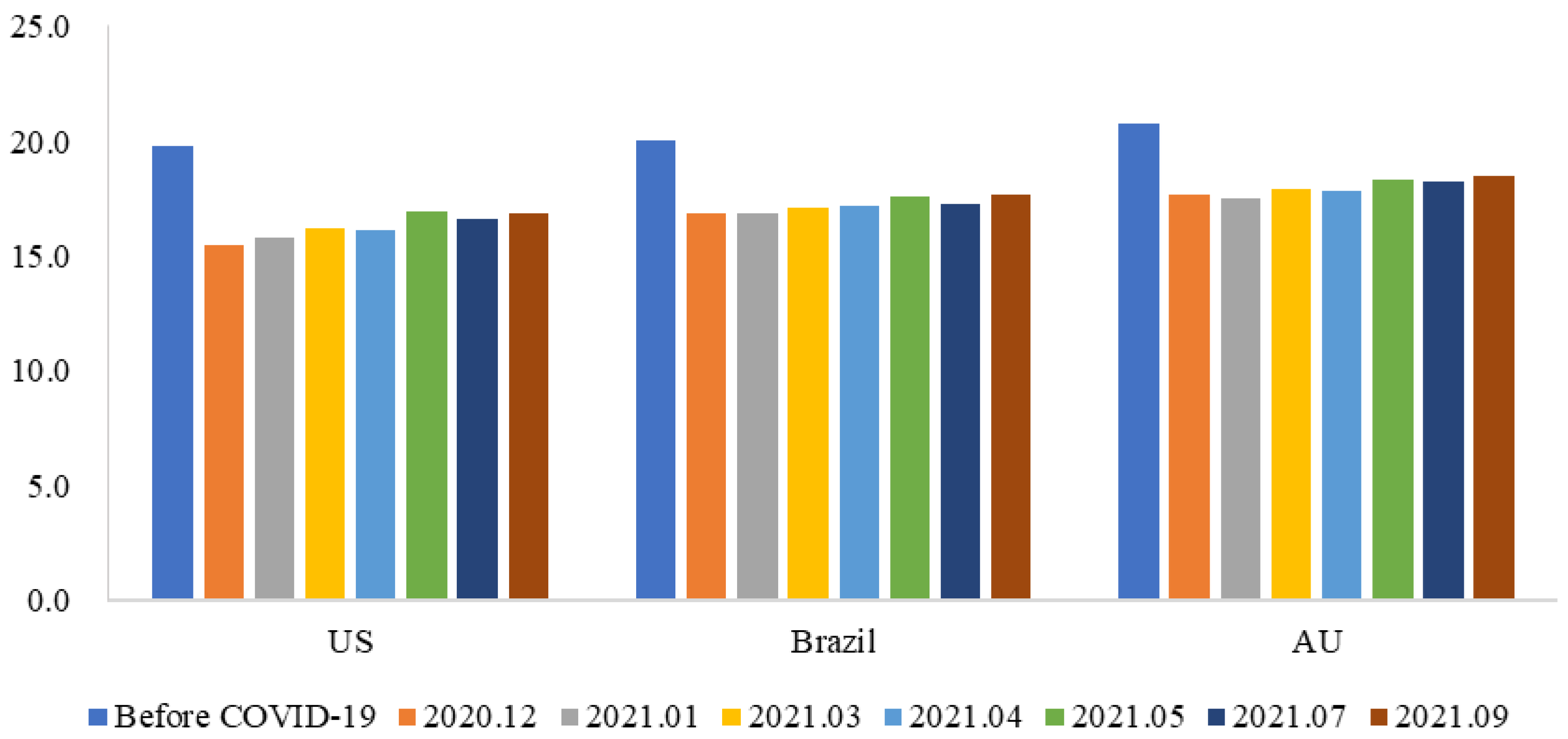

3.3. Willingness to Pay for Imported Cold-Chain Beef

3.4. Respondents’ Characteristics Associated with Risk Perception of Imported Cold-Chain Beef

3.5. Factors Influencing Willingness to Pay for Imported Cold-Chain Beef

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | UPDATED: Timeline of the Coronavirus|Think Global Health, n.d. (https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/updated-timeline-coronavirus (accessed on 12 July 2022)). |

| 2 | State-by-State Coronavirus-Related Restrictions. AARP (https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/government-elections/info-2020/coronavirus-state-restrictions.html (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 3 | UPDATED: Timeline of the Coronavirus|Think Global Health, n.d. (https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/updated-timeline-coronavirus (accessed on 12 July 2022)). |

| 4 | Brazil’s Marfrig says 25 workers tested positive for COVID-19 at beef plant (https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-marfrig-idUSL1N2D70EJ/ (accessed on 12 July 2022)). Alberta beef plant halts slaughter due to positive COVID-19 test (https://nationalpost.com/pmn/health-pmn/alberta-beef-plant-halts-slaughter-due-to-positive-covid-19-test (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 5 | COVID-19 virus found on imported frozen beef samples (https://www.thehealthsite.com/news/covid-19-virus-found-on-imported-frozen-beef-samples-780594/ (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 6 | Chinese consumers are turning away from imported meat due to COVID-19 fears (https://www.thepigsite.com/news/2021/01/chinese-consumers-are-turning-away-from-imported-meat-due-to-covid-19-fears (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 7 | China accounts for 25% of the global meat trade—UBI Meat Experts in QA, n.d. (https://ubibeefinspection.com/2019/09/03/china-accounts-for-25-of-the-global-meat-trade/ (accessed 12 August 2022)). |

| 8 | Beef and Beef Products 2021 Export Highlights (WWW Document), n.d. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (https://www.fas.usda.gov/beef-2021-export-highlights (accessed 12 August 2022)). |

| 9 | Australia’s beef trade with China|Meat and Livestock Australia (WWW Document), n.d. MLA Corporate (https://www.mla.com.au/news-and-events/industry-news/australias-beef-trade-with-china/ (accessed 12 August 2022)). |

| 10 | USDA ERS—Brazil Once Again Becomes the World’s Largest Beef Exporter (WWW Document), n.d. (https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2019/july/brazil-once-again-becomes-the-world-s-largest-beef-exporter/ (accessed 12 August 2022)). |

| 11 | Although the price of a beef steak in China ranged from 12 yuan to more than 100 yuan because of different quality, the dominant price is about 20 yuan, and the payment card includes the most popular prices in the market. |

| 12 | China steps up measures in cold-chain transportation to contain winter resurgence of COVID-19, CGTN (https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-11-13/China-targets-cold-chain-transport-to-contain-winter-spike-of-COVID-19-Vo3p84JDwc/index.html (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 13 | COVID-19 certificates needed for imported meat, aquatic products (https://www.newsgd.com/node_99363c4f3b/dbd035af80.shtml (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

| 14 | Steer the middle course, China Daily (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202112/28/WS61ca7de3a310cdd39bc7de06.html (accessed 12 July 2022)). |

References

- Amemiya, T. (1973). Regression analysis when the dependent variable is truncated normal. Econometrica, 41(6), 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics using stata (Vol. 2). Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chenarides, L., Grebitus, C., Lusk, J. L., & Printezis, I. (2021). Food consumption behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness, 37(1), 44–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ding, D., & Zhang, R. (2022). China’s COVID-19 control strategy and its impact on the global pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 857003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, C., Thomas, R., & Torgerson, D. J. (1997). Validity of open-ended and payment scale approaches to eliciting willingness to pay. Applied Economics, 29(1), 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dyal, J. W. (2020). COVID-19 among workers in meat and poultry processing facilities—19 states, April 2020. Mmwr Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(18), 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, E. J., Osterholm, M., & Gounder, C. R. (2022). A national strategy for the “new normal” of life with covid. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 327(3), 211–212. [Google Scholar]

- Faour-Klingbeil, D., Osaili, T. M., Al-Nabulsi, A. A., Jemni, M., & Todd, E. C. D. (2021). The public perception of food and non-food related risks of infection and trust in the risk communication during COVID-19 crisis: A study on selected countries from the Arab region. Food Control, 121, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K. G. (2002). Current issues in the understanding of consumer food choice. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 13(8), 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, N., & Wang, H. H. (2021). Food consumption and stigmatization under COVID-19: Evidence from Chinese consumers’ aversion to Wuhan hot instant noodles. Agribusiness, 37(1), 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromi, H., Yuko, K., & Tsutomu, S. (2012). How do Japanese consumers perceive radiation risks in food? Japanese Journal of Risk Analysis, 22(4), 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecinski, M., Keisner, D. K., Messer, K. D., & Schulze, W. D. (2016). Stigma mitigation and the importance of redundant treatments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecinski, M., & Messer, K. D. (2018). Mitigating public concerns about recycled drinking water: Leveraging the power of voting and communication. Water Resources Research, 54(8), 5300–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W., Ortega, D. L., Ufer, D., Caputo, V., & Awokuse, T. (2022). Blockchain-based traceability and demand for US beef in China. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 44(1), 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüth, S., Boone, I., Kleta, S., & Al Dahouk, S. (2019). Analysis of RASFF notifications on food products contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes reveals options for improvement in the rapid alert system for food and feed. Food Control, 96, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, L., Puertas, R., & García-Álvarez-Coque, J. M. (2021). The effects on European importers’ food safety controls in the time of COVID-19. Food Control, 125, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, B. R., & Lusk, J. L. (2015). Cognitive biases in the assimilation of scientific information on global warming and genetically modified food. Food Policy, 54, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, B. R., Malone, T., Kecinski, M., & Messer, K. D. (2021). COVID-19 Induced Stigma in US Consumers: Evidence and Implications. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 103(2), 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, K. D., Costanigro, M., & Kaiser, H. M. (2017). Labeling food processes: The good, the bad and the ugly. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 39(3), 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. C., & Carson, R. T. (1981). An experiment in determining willingness to pay for national water quality improvements. Resources for the Future Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nakat, Z., & Bou-Mitri, C. (2021). COVID-19 and the food industry: Readiness assessment. Food Control, 121, 107661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, C. L., & Holcomb, R. B. (2019). Does a food safety label matter? Consumer heterogeneity and fresh produce risk perceptions under the Food Safety Modernization Act. Food Policy, 85(C), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D. L., Hong, S. J., Wang, H. H., & Wu, L. (2016). Emerging markets for imported beef in China: Results from a consumer choice experiment in Beijing. Meat Science, 121, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ready, R. C., Navrud, S., & Dubourg, W. R. (2001). How Do Respondents with uncertain willingness to pay answer contingent valuation questions? Land Economics, 77(3), 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. (2001). Technological stigma: Some perspectives from the study of contagion. In J. Flynn, P. Slovic, & H. Kunreuther (Eds.), Risk, media, and stigma: Understanding public challenges to modern science and technology (pp. 31–40). Earthscan Publication Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, W., & Wansink, B. (2012). Toxics, toyotas, and terrorism: The behavioral economics of fear and stigma. Risk Analysis an Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 32(4), 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. E., Inbar, Y., & Rozin, P. (2016). Evidence for absolute moral opposition to genetically modified food in the United States. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, S., Niiyama, Y., Kito, Y., Kudo, H., & Yamaguchi, M. (2018, July 28–August 2). No-tolerant consumers, information treatments, and demand for stigmatized foods: The case of Fukushima nuclear power plant accident in Japan. 2018 Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P., Peters, E., Finucane, M. L., & MacGregor, D. G. (2005). Affect, risk, and decision making. Health Psychology, 24(4S), S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, K., Yamamoto, M., & Ichinose, D. (2016). How do agricultural markets respond to radiation risk? Evidence from the 2011 disaster in Japan. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 60, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsor, G. T., Lusk, J. L., & Tonsor, S. L. (2021). Meat demand monitor during covid-19. Animals, 11(4), 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V. (2013). Defining and identifying“Stigma”. In P. Slovic, H. Kunreuther, & J. Flynn (Eds.), Risk, media and stigma: Understanding public challenges to modern science and technology (pp. 369–376). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E., Ji, M., Wang, L., Wu, Y., & Shi, Z. (2024). The role of country image on consumers’ willingness to pay for imported beefsteak in China. Foods, 13(6), 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E., Ning, A. N., Geng, X., Zhifeng, G., & Kiprop, E. (2021). Consumers’ willingness to pay for ethical consumption initiatives on e-commerce platforms. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 20(4), 1012–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S., Qing, P., Hu, W., & Liu, Y. (2014). Product information and Chinese consumers’ willingness-to-pay for fair trade coffee. China Agricultural Economic Review, 6(2), 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X., Gao, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2014). Willingness to pay for the “Green Food” in China. Food Policy, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Previous purchase frequency of imported cold-chain food | How often do you purchase imported cold-chain food? | 1 = none, 6 = very much |

| Perception of imported cold-chain food contaminated with Novel Coronavirus entering the market | What do you think of the risk of imported cold-chain food contaminated with Novel Coronavirus entering the market this month? | 1 = extremely low risk, 5 = extremely high risk |

| Perception of getting COVID-19 from cold-chain food | What do you think is the risk of getting COVID-19 from cold-chain food? | 1 = extremely low risk, 5 = extremely high risk |

| Risk perception of contamination with Novel Coronavirus from the U.S./Australia/Brazil | What do you think of the imported cold-chain food contaminated with Novel Coronavirus from the following countries: U.S./Australia/Brazil? | 1 = extremely low risk, 5 = extremely high risk |

| Willingness to pay for cold-chain beef from different countries | Assume that the price for a piece of domestic frozen filet mignon (150 g) is 20 yuan. What is the maximum acceptable price for the same piece of frozen filet mignon from the U.S./Australia/Brazil? | Under 16 yuan, 16–18 yuan, 18–20 yuan, 20–22 yuan, 22–24 yuan, 24–26 yuan, 26–28 yuan, 26–30 yuan, or 30 yuan or above. |

| Survey | Time | Size of Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Survey round 1 | 20–28 December 2020 | 340 |

| Survey round 2 | 20–23 January 2021 | 434 |

| Survey round 3 | 19–23 March 2021 | 379 |

| Survey round 4 | 20–23 April 2021 | 374 |

| Survey round 5 | 27–28 May 2021 | 330 |

| Survey round 6 | 19–20 July 2021 | 334 |

| Survey round 7 | 1–2 October 2021 | 379 |

| Variable | December 2020 (N = 322) | January 2021 (N = 418) | March 2021 (N = 355) | April 2021 (N = 364) | May 2021 (N = 317) | July 2021 (N = 323) | October 2021 (N = 379) | Pooled Sample (N = 2570) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.579 | 0.502 | 0.544 | 0.543 | 0.506 | 0.524 | 0.565 | 0.537 |

| Age | 30.753 | 30.917 | 30.422 | 30.610 | 31.485 | 30.895 | 30.583 | 30.798 |

| Education level | 0.874 | 0.924 | 0.942 | 0.925 | 0.936 | 0.907 | 0.958 | 0.925 |

| Income1 | 0.059 | 0.035 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.036 | 0.048 | 0.042 | 0.046 |

| Income2 | 0.179 | 0.184 | 0.172 | 0.160 | 0.130 | 0.153 | 0.113 | 0.157 |

| Income3 | 0.229 | 0.244 | 0.219 | 0.233 | 0.209 | 0.231 | 0.211 | 0.226 |

| Income4 | 0.206 | 0.182 | 0.219 | 0.235 | 0.252 | 0.207 | 0.208 | 0.214 |

| Income5 | 0.112 | 0.196 | 0.137 | 0.150 | 0.188 | 0.138 | 0.169 | 0.157 |

| Income6 | 0.115 | 0.078 | 0.116 | 0.102 | 0.121 | 0.129 | 0.145 | 0.114 |

| Income7 | 0.100 | 0.081 | 0.087 | 0.070 | 0.064 | 0.096 | 0.111 | 0.087 |

| Children | 0.597 | 0.560 | 0.657 | 0.586 | 0.682 | 0.665 | 0.720 | 0.636 |

| Perception of Imported Cold-Chain Food Contaminated with Novel Coronavirus Entering Market | Perception of Getting COVID-19 from Cold-Chain Food | |

|---|---|---|

| Survey time | −0.759 *** | −0.279 *** |

| (0.093) | (0.093) | |

| Survey time squared | 0.0636 *** | 0.0227 ** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Female | 0.074 | −0.0586 |

| (0.076) | (0.078) | |

| Age | 0.0147 *** | 0.0110 ** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Education level | 0.140 | −0.0976 |

| (0.154) | (0.159) | |

| Income2 | 0.106 | 0.0246 |

| (0.206) | (0.211) | |

| Income3 | 0.148 | 0.0595 |

| (0.202) | (0.207) | |

| Income4 | 0.259 | 0.109 |

| (0.204) | (0.209) | |

| Income5 | 0.417 ** | 0.233 |

| (0.211) | (0.217) | |

| Income6 | −0.0151 | −0.0147 |

| (0.219) | (0.225) | |

| Income7 | 0.192 | 0.273 |

| (0.229) | (0.236) | |

| Children | 0.242 *** | 0.324 *** |

| (0.083) | (0.085) |

| Variables | Imported U.S. | Imported Brazil | Imported Australia |

|---|---|---|---|

| WTPbefore | 0.576 *** | 0.535 *** | 0.527 *** |

| (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| Risk perception of contamination with Novel Coronavirus from U.S./Australia/Brazil | −1.288 *** | −0.851 *** | −0.884 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.103) | (0.104) | |

| Perception of getting COVID-19 from cold-chain food | −0.586 *** | −0.322 *** | −0.423 *** |

| −0.139 | −0.109 | −0.114 | |

| Perception of imported cold-chain food contaminated with Novel Coronavirus entering the market | −0.171 | −0.189 ** | −0.219 ** |

| (0.122) | (0.096) | (0.100) | |

| Previous purchase frequency of imported cold-chain food | 0.320 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.307 *** |

| (0.094) | (0.074) | (0.077) | |

| Female | −0.0799 | 0.0891 | 0.0454 |

| (0.215) | (0.170) | (0.176) | |

| Age | −0.0353 ** | −0.0158 | −0.0273 ** |

| (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| Education level | −0.417 | −0.205 | −0.513 |

| (0.451) | (0.354) | (0.366) | |

| Income2 | −0.105 | −0.235 | −0.244 |

| (0.608) | (0.469) | (0.495) | |

| Income3 | 0.331 | −0.0327 | 0.1 |

| (0.593) | (0.458) | (0.482) | |

| Income4 | −0.551 | −0.533 | −0.182 |

| (0.600) | (0.464) | (0.488) | |

| Income5 | −0.266 | −0.00448 | −0.00736 |

| (0.619) | (0.478) | (0.503) | |

| Income6 | −0.556 | −0.759 | −0.515 |

| (0.643) | (0.499) | (0.524) | |

| Income7 | −0.736 | −0.732 | −0.553 |

| (0.670) | (0.521) | (0.546) | |

| Children | 0.349 | 0.0576 | 0.0094 |

| (0.238) | (0.187) | (0.195) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, E. COVID-19 Induced Stigmas of Imported Cold-Chain Food Among Chinese Consumers: Multi-Round Tracking Surveys. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040421

Wang E. COVID-19 Induced Stigmas of Imported Cold-Chain Food Among Chinese Consumers: Multi-Round Tracking Surveys. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040421

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Erpeng. 2025. "COVID-19 Induced Stigmas of Imported Cold-Chain Food Among Chinese Consumers: Multi-Round Tracking Surveys" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040421

APA StyleWang, E. (2025). COVID-19 Induced Stigmas of Imported Cold-Chain Food Among Chinese Consumers: Multi-Round Tracking Surveys. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040421