Variability and Belief in Karma: Perceived Life Variability Polarizes Perceptions of Behavior–Outcome Valence Consistency

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Life Variability and Belief in Karma

1.2. Current Research

2. Study 1a

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Materials and Procedure

2.2. Results and Discussion

2.2.1. Manipulation Checks

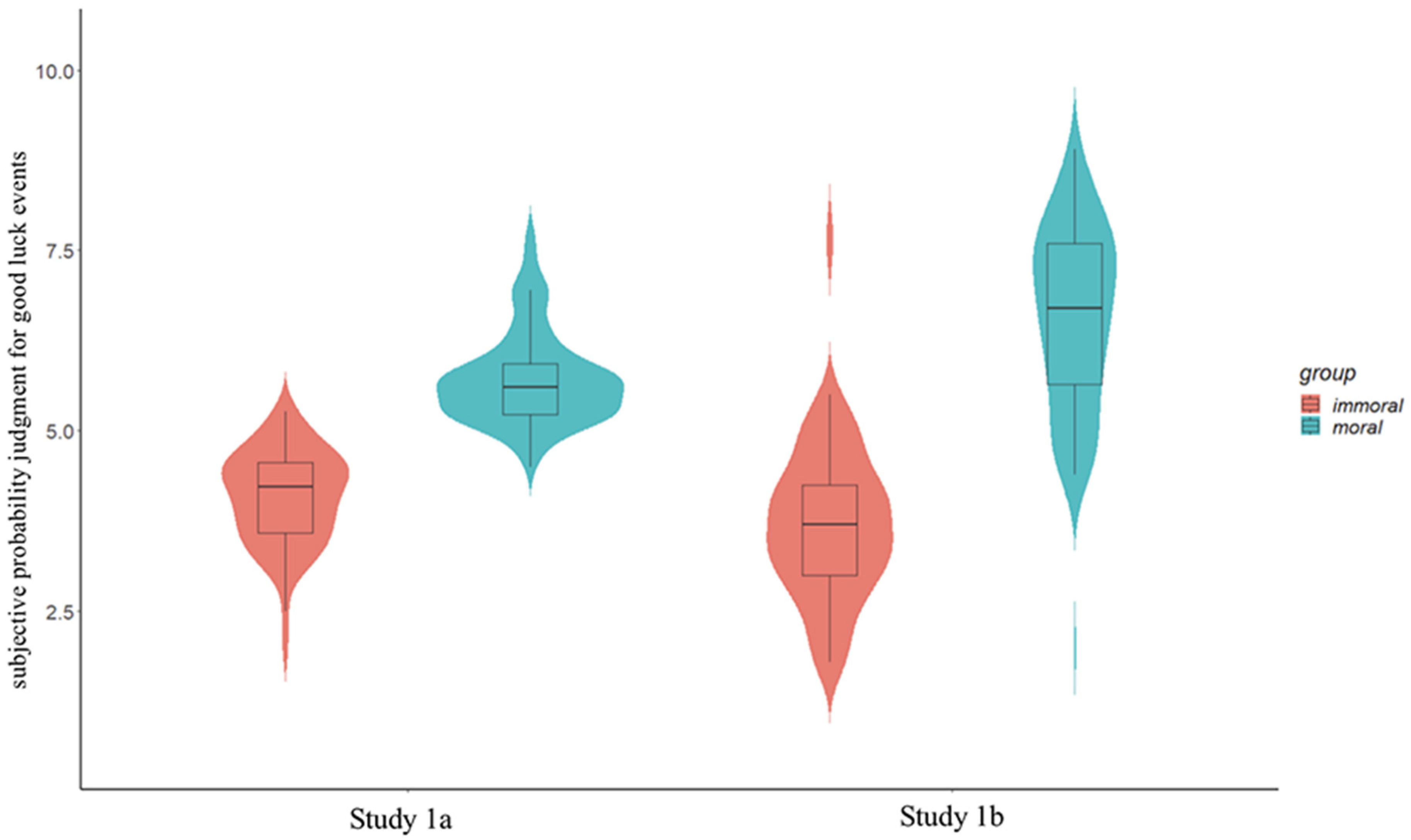

2.2.2. Subjective Probability Judgment for Good Luck Events

3. Study 1b

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials and Procedure

3.2. Results and Discussion

3.2.1. Manipulation Checks

3.2.2. Subjective Probability Judgment for Good Luck Events

4. Study 2

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Materials and Procedure

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. General Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam-Troian, J., Chayinska, M., Paladino, M. P., Uluğ, Ö. M., Vaes, J., & Wagner-Egger, P. (2023). Of precarity and conspiracy: Introducing a socio-functional model of conspiracy beliefs. British Journal of Social Psychology, 62(S1), 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, P. M., Edwards, J. A., & McCullough, W. (2015). Does karma exist?: Buddhism, social cognition, and the evidence for karma. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 25(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K., & Bloom, P. (2017). You get what you give: Children’s karmic bargaining. Developmental Science, 20(5), e12442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, B., & Haisken-DeNew, J. P. (2019). Keep calm and consume? Subjective uncertainty and precautionary savings. Journal of Economics and Finance, 43(3), 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, O., Hammill, A., & McLeman, R. (2007). Climate change as the “new” security threat: Implications for Africa. International Affairs, 83(6), 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtel, E. E., Guan, Y., Peng, Q., Su, Y., Sang, B., Chen, S. X., & Bond, M. H. (2015). Immorality East and West: Are immoral behaviors especially harmful, or especially uncivilized? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(10), 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J. M., & Cooper, H. M. (1979). The desirability of control. Motivation and Emotion, 3(4), 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, M. J., Ferguson, H. J., & Bindemann, M. (2013). Eye movements to audiovisual scenes reveal expectations of a just world. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(1), 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converse, B. A., Risen, J. L., & Carter, T. J. (2012). Investing in karma: When wanting promotes helping. Psychological Science, 23(8), 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coultas, C., Reddy, G., & Lukate, J. (2022). Towards a social psychology of precarity. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64(3), 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S. B. (1983). The tool box approach of the Tamil to the issues of moral responsibility and human destiny. In C. F. Keyes, & E. V. Daniel (Eds.), Karma: An anthropological inquiry (pp. 27–62). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. R. T., Connor, K. M., & Li-Ching, L. (2005). Beliefs in karma and reincarnation among survivors of violent trauma: A community survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(2), 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witte, H., De Cuyper, N., Handaja, Y., Sverke, M., Näswall, K., & Hellgren, J. (2010). Associations between quantitative and qualitative job insecurity and well-being. International Studies of Management and Organization, 40(1), 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S. (2018). Law of Karma: Just our moral balance sheet or a path to sagehood and fulfillment? In The palgrave handbook of workplace spirituality and fulfillment (pp. 513–541). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., & Savani, K. (2020). From variability to vulnerability: People exposed to greater variability judge wrongdoers more harshly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(6), 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranseika, V., Berniūnas, R., & Silius, V. (2018). Immorality and bu daode, unculturedness and bu wenming. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, 2(1–2), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feather, N. T. (1992). An attributional and value analysis of deservingness in success and failure situations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 31(2), 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, N., & Keinan, G. (1991). The effects of stress, ambiguity tolerance, and trait anxiety on the formation of causal relationships. Journal of Research in Personality, 25(1), 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, I., Jonas, E., & Fankhänel, T. (2008). The role of control motivation in mortality salience effects on ingroup support and defense. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, B. M., Randel, A. E., Collins, B. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M. J., Nishii, L. H., & Raver, J. L. (2006). On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Meindl, P., Beall, E., Johnson, K. M., & Zhang, L. (2016). Cultural differences in moral judgment and behavior, across and within societies. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griskevicius, V., Ackerman, J. M., Cantú, S. M., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Simpson, J. A., Thompson, M. E., & Tybur, J. M. (2013). When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments. Psychological Science, 24(2), 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Guo, Y., Qiao, X., Leng, J., & Lv, Y. (2021). Chance locus of control predicts moral disengagement which decreases well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehner, P., Kritzler, S., Fassbender, I., & Luhmann, M. (2022). Stability and change of perceived characteristics of major life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(6), 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K. K. (2012). Foundations of Chinese psychology: Confucian social relations. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., Chang, C. H. D., & Lin, S. H. J. (2016). Assessing the status of locus of control as an indicator of core self-evaluations. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. C., Moscovitch, D. A., & Laurin, K. (2010). Randomness, attributions of arousal, and belief in god. Psychological Science, 21, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. C., Whitson, J. A., Gaucher, D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Compensatory control: Achieving order through the mind, our institutions, and the heavens. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinan, G. (2002). The effects of stress and desire for control on superstitious behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(1), 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P., & Khanna, J. L. (2007). Locus of control in India: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 14(1–4), 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisala, R. (1994). Contemporary karma: Interpretations of karma in Tenrikyō and Risshō Kōseikai. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 21(1), 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulow, K., & Kramer, T. (2016). In pursuit of good karma: When charitable appeals to do right go wrong. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(2), 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, M. J., Kay, A. C., & Whitson, J. A. (2015). Compensatory control and the appeal of a structured world. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 694–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurin, K., & Kay, A. C. (2017). The motivational underpinnings of belief in God. In J. M. Olson (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 201–257). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, K., Gaucher, D., & Kay, A. (2013). Stability and the justification of social inequality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(4), 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBoeuf, R. A., & Norton, M. I. (2012). Consequence-cause matching: Looking to the consequences of events to infer their causes. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(1), 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. (2012). Beliefs in Chinese culture. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 221–240). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. S. (1995). The concepts of “paoying” and “karma”: An example of syncretism (Order No. 1377826). [Master’s thesis, Western Michigan University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/concepts-paoying-karma-example-syncretism/docview/304251473/se-2 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., & Ranasinghe, P. (2009). Causal thinking after a tsunami wave: Karma beliefs, pessimistic explanatory style and health among Sri Lankan survivors. Journal of Religion and Health, 48(1), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. (1939). Field theory and experiment in social psychology: Concepts and methods. American Journal of Sociology, 44(6), 868–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P., & Suwankhong, D. (2016). Living with breast cancer: The experiences and meaning-making among women in southern Thailand. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(3), 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., & Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(7), 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., & Liao, J. (2020). Superstition makes you less deontological: Explaining the moral function of superstition by compensatory control theory. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 14(2), 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 592–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupfer, M. B., & Gingrich, B. E. (1999). When bad (good) things happen to good (bad) people: The impact of character appraisal and perceived controllability on judgments of deservingness. Social Justice Research, 12(3), 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A., Savani, K., Liu, F., Tai, K., & Kay, A. C. (2022). The mutual constitution of culture and psyche: The bidirectional relationship between individuals’ perceived control and cultural tightness–looseness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(5), 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, A., & Simão, C. (2020). Karmic forecasts: The role of justice in forecasts about self and others. Motivation Science, 6(4), 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, C., Zhang, R., Karnatak, T., Lamba, N., & Khokhlova, O. (2023). Just wrong? Or just WEIRD? Investigating the prevalence of moral dumbfounding in non-Western samples. Memory and Cognition, 51(5), 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, Z., & Krishnan, V. (2007). Karma-Yoga: Construct validation using value systems and emotional intelligence. South Asian Journal of Management, 14(4), 116–137. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A., Henrich, J., Curtin, C., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J., & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, S. (2014). Socioecological psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östervall, A. (2022). Belief in karma and political attitudes [Master’s dissertation, Uppsala University]. [Google Scholar]

- Pepitone, A., & Saffiotti, L. (1997). The selectivity of nonmaterial beliefs in interpreting life events. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T. M., & Desrosiers, M. (1980). Measurement of supernatural belief: Sex differences and locus of control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 44(5), 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., Rabbanee, F. K., Roy Chaudhuri, H., & Menon, P. (2020). The karma of consumption: Role of materialism in the pursuit of life satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, R. L., Allen, T. A., & Masten, A. S. (2017). Adversity in adolescence predicts personality trait change from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Research in Personality, 67, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, O., & Meckel, A. (2017). The role of magical thinking in forecasting the future. British Journal of Psychology, 108(1), 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.-L., Mayer, D. K., Chou, F.-H., & Hsiao, K.-Y. (2016). The experience of cancer stigma in Taiwan: A qualitative study of female cancer patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(2), 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S. J., & Guo, Y. Y. (2019). The social survey of karma and priming experiment of inhibition effect on machiavellian behavior. Psychological Exploration, 39(4), 352–357. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigen, K. H., Evensen, P. C., Samoilow, D. K., & Vatne, K. B. (1999). Good luck and bad luck: How to tell the difference. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(8), 981–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. K., Ericksen, P. J., Herrero, M., & Challinor, A. J. (2014). Climate variability and vulnerability to climate change: A review. Global Change Biology, 20(11), 3313–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vail, K. E., Rothschild, Z. K., Weise, D. R., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (2010). A terror management analysis of the psychological functions of religion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadley, S. S. (1983). Vrats: Transformers of destiny. In C. F. Keyes, & E. V. Daniel (Eds.), Karma: An anthropological inquiry (pp. 147–162). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, C. J. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2019). Belief in karma: How cultural evolution, cognition, and motivations shape belief in supernatural justice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 60, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. J. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2022). Karma and god: Convergent and divergent mental representations of supernatural norm enforcement. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 14(1), 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. J. M., Baimel, A., & Norenzayan, A. (2017). What are the causes and consequences of belief in karma? Religion, Brain and Behavior, 7(4), 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. J. M., Kelly, J. M., Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2019a). Supernatural norm enforcement: Thinking about karma and God reduces selfishness among believers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 84, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. J. M., Norenzayan, A., & Schaller, M. (2019b). The content and correlates of belief in karma across cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(8), 1184–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C. J. M., Willard, A. K., Baimel, A., & Norenzayan, A. (2021). Cognitive pathways to belief in karma and belief in God. Cognitive Science, 45(1), e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, A. K., Baimel, A., Turpin, H., Jong, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2020). Rewarding the good and punishing the bad: The role of karma and afterlife beliefs in shaping moral norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(5), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C., & Cheng, C. (2010). Terror management among Taiwanese: Worldview defence or resigning to fate? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(3), 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C. L. (2012). It is our destiny to die: The effects of mortality salience and culture-priming on fatalism and karma belief. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Events | Moral | Immoral | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | d | 95% CI | |

| Get a better job | 5.79 | 1.44 | 2.77 | 1.49 | 11.76 ** | 2.06 | [2.51, 3.52] |

| Have good luck | 5.80 | 1.40 | 3.48 | 1.52 | 9.03 ** | 1.59 | [1.81, 2.82] |

| Receive CNY 1000 as a gift from a stranger | 5.73 | 2.01 | 3.21 | 1.54 | 7.96 ** | 1.39 | [1.89, 3.14] |

| Accidentally find a CNY 100 bill on the sidewalk | 4.94 | 1.03 | 4.18 | 1.23 | 3.81 ** | 0.68 | [0.37, 1.16] |

| Be very fortunate in life | 5.29 | 1.18 | 3.28 | 1.33 | 9.07 ** | 1.60 | [1.57, 2.45] |

| Always “be in the right place at the right time” | 5.47 | 1.25 | 2.92 | 1.37 | 11.16 ** | 1.94 | [2.10, 3.01] |

| Spend no night in a hospital for 10 years | 4.54 | 1.72 | 3.90 | 1.54 | 2.24 * | 0.39 | [0.08, 1.20] |

| Win a lottery | 4.74 | 1.22 | 3.88 | 1.55 | 3.46 ** | 0.62 | [0.37, 1.35] |

| Earn a lot of money | 4.86 | 1.40 | 3.33 | 1.41 | 6.22 ** | 1.09 | [1.04, 2.02] |

| Average: positive events | 5.24 | 0.66 | 3.44 | 0.95 | 12.44 ** | 2.20 | [1.51, 2.09] |

| Fall victim to a brutal assault | 3.57 | 1.54 | 6.57 | 1.77 | −10.41 ** | −1.82 | [−3.57, −2.43] |

| Contract HIV through blood transfusion | 3.29 | 1.78 | 4.52 | 1.64 | −4.15 ** | −0.72 | [−1.83, −0.65] |

| Be victim of a natural disaster | 4.54 | 1.64 | 4.92 | 1.44 | −1.37 | −0.24 | [−0.91, 0.17] |

| Be bullied by colleagues | 3.40 | 1.77 | 6.03 | 1.96 | −8.05 ** | −1.42 | [−3.28, −1.99] |

| Find wallet was stolen | 4.46 | 1.15 | 5.54 | 1.35 | −4.96 ** | −0.87 | [−1.52, −0.65] |

| Die in a car accident | 3.56 | 1.69 | 4.74 | 1.40 | −4.37 ** | −0.76 | [−1.72, −0.65] |

| Have bad luck | 4.39 | 1.28 | 5.70 | 1.42 | −5.60 ** | −0.98 | [−1.79, −0.85] |

| Be cruelly murdered | 3.14 | 1.69 | 4.90 | 1.97 | −5.50 ** | −0.96 | [−2.39, −1.13] |

| Lose a loved one in a car accident | 3.99 | 1.59 | 4.90 | 1.43 | −3.46 ** | −0.60 | [−1.22, −0.39] |

| Average: negative events | 3.81 | 1.04 | 5.31 | 0.82 | −9.22 ** | −1.60 | [−1.82, −1.18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiao, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Y. Variability and Belief in Karma: Perceived Life Variability Polarizes Perceptions of Behavior–Outcome Valence Consistency. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040400

Jiao L, Guo Z, Zhao J, Xu Y. Variability and Belief in Karma: Perceived Life Variability Polarizes Perceptions of Behavior–Outcome Valence Consistency. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040400

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiao, Liying, Zhen Guo, Jinzhe Zhao, and Yan Xu. 2025. "Variability and Belief in Karma: Perceived Life Variability Polarizes Perceptions of Behavior–Outcome Valence Consistency" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040400

APA StyleJiao, L., Guo, Z., Zhao, J., & Xu, Y. (2025). Variability and Belief in Karma: Perceived Life Variability Polarizes Perceptions of Behavior–Outcome Valence Consistency. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040400