Analysis of Economic Activity Participation and Determining Factors Among Married Women by Income Level After the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Life Satisfaction and Participation in Economic Activities of Married Women

2.2. Women’s Economic Activity Participation After the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.3. Characteristics of Women’s Participation in Economic Activity in South Korea

2.4. Factors Influencing the Participation in Economic Activity of Married Women

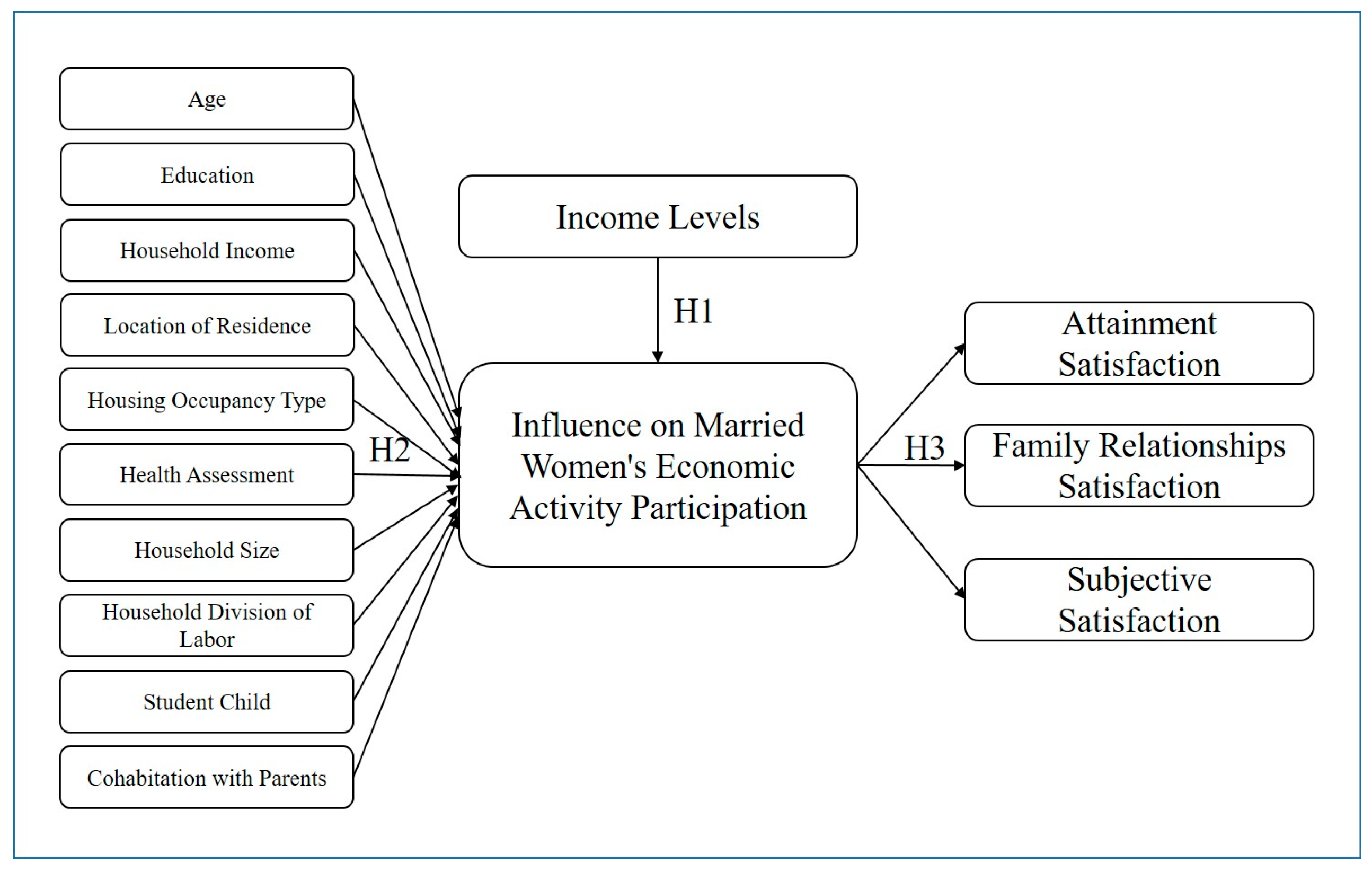

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses Development

4. Method and Data Resource

4.1. Collecting Data

4.2. Setting Variables

4.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2.2. Social Environment Factors

4.2.3. Income Bracket Classifications

4.3. Analytic Strategies

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Results

5.2. Regression Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdo Ahmad, I., Fakih, A., & Hammoud, M. (2023). Parents’ perceptions of their children’s mental health during COVID-19: Evidence from Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 337, 116298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, S., & Kim, J. Y. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 recession on the US labor market: Occupation, family, and gender. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(3), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. B. (2007). The distribution of earnings in OECD countries. International Labour Review, 146(1–2), 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K. H., & Kim, S. J. (2012). Moderating effect of social capital in regards to the influence that family income and job status have on the level of satisfaction with family relationships among married immigrant women. Korean Journal of Social Welfare, 64(3), 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(3), 393–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H. J. (2022). The effect of subjective living standards and perceptions on life satisfaction of middle-aged and elderly women: Focusing on the Gyeongsangnam-do social survey. [The effect of subjective living standards and perceptions on life satisfaction of middle-aged and elderly women: Focusing on the Gyeongsangnam-do social survey]. Korean Journal of Growth and Development, 30(4), 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. Y., & Cheon, B. Y. (2014). Female labor supply and its impacts on household level income inequality. Korean Journal of Labor Studies, 20(2), 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. E., & Yoo, S. J. (2009). A study on the effectiveness of childcare policies. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. M., Kim, C. W., Park, H. O., & Park, Y. T. (2023). Association between unpredictable work schedule and work-family conflict in Korea. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 35, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Choi, Y. H., & Won, S. Y. (2020). The effects of cost of children on fertility rate: Focusing on OECD countries. Korean Policy Studies Review, 29(3), 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2021). COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, B. W. (2020). Short-run effects of COVID-19 on US worker transitions. School of Economic Sciences, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, S. (2022). Gender and telework: Work and family experiences of teleworking professional, middle-class, married women with children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(1), 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, C., & Hunt, K. (2009). ‘Live to work’ or ‘work to live’? A qualitative study of gender and work–life balance among men and women in mid-life. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(1), 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinn, C. C., Samantha, L. H., Janine, M. R., Fiona, J. C., & Kristine, M. J. (2021). COVID-19 and women. International Perspectives in Psychology, 10(3), 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evlilik, Ç. V., & Doyumu, Ö. (2017). A comparative study of employed and unemployed married women in the context of marital satisfaction, self-esteem and psychological well-being. Journal of Neurobehavioral Siences, 4(3), 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, C., Kerr, S. P., & Olivetti, C. (2022). When the kids grow up: Women’s employment and earnings across the family cycle. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gurín, M. (2023). Forgotten concepts of Korea’s welfare state: Productivist welfare capitalism and confucianism revisited in family policy change. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 30(4), 1211–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S. (2021). Explaining gender gaps in the south Korean labor market during the COVID-19 pandemic. Feminist Economics, 27(1/2), 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M. (2025). Structural changes in South Korea employment (2000–2021). In S. Torrejón Pérez, E. Fernández-Macías, & J. Hurley (Eds.), Global trends in job polarisation and upgrading: A comparison of developed and developing economies (pp. 297–320). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M. J. (2003). A causal relation of employment and depression among low-income young mothers in new chance demonstration study. Human Ecology Research, 41(7), 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. M., Kang, Y. N., & Jang, Y. S. (2011). A longitudinal study on the effects of the social service continuity on married women’s labor force participation and employment patterns: Using a mixed-effects multinominal logistic regression model. Health and Social Welfare Review, 31(3), 38–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, B. H. (2010). Study on the effect of expansion in childcare subsidy on female labour force participation. University of Seoul. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. Y., Lee, W. J., Ham, S. Y., & Wang, J. S.-H. (2024). Motherhood or marriage penalty? A comparative perspective on employment and wage in East Asia and Western countries. Family Relations, 73(1), 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. S., & Yoon, O. H. (2009). A study on the QOL of married working women: Focused on structural relations between effecting factors. Korean Journal of Local Government & Administration Studies, 23(2), 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. O., & Park, Y. H. (2021). Medical service satisfaction and social safety perception towards the new diseases and influencing factors: Focusing on 2018 and 2020. Social Survey, 15(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Y., & Shin, J. S. (2022). The effect of working hours on marital satisfaction in the job culture of married women: The moderating effect of household labor sharing. Journal of Korea Culture Industry, 22(4), 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J., & Kim, E. J. (2007). Housework and economic dependency among dual-earner couples in Korea—Economic exchange or gender compensation? Korean Journal of Sociology, 41(2), 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H. J., & Choi, E. Y. (2015). Influence factors of labor force participation for married women: Focusing on the gender unequal structure in household and labor market. Women’s Studies, 88(1), 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. J. (2021). Differences in women’s perceptions to the policy response in Korea to its low birth rate: An empirical investigation using Q-methodology. Korean Policy Studies Review, 30(3), 77–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. W. (2020). Changes and new directions of community welfare in the era of new normal after COVID-19. Journal of Community Welfare, 74, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Z., & Wang, S. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P. A. (2011). Heterogeneous impact of Taiwan’s national health insurance on labor force participation of married women by income and family structures. Health Care for Women International, 32(2), 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K., & Zabek, M. (2023). Women’s labor force exits during COVID-19: Differences by motherhood, race, and ethnicity. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 45(3), 504–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maume, D. J. (2008). Gender differences in providing urgent childcare among dual-earner parents. Social Forces, 87(1), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. (2000). Coefficients of determination for multiple logistic regression analysis. The American Statistician, 54(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S. H. (2011). Fear of crime in Korea: Analysis of the social survey data. Police Science Journal, 6(1), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenovo, L., Jiang, X., Lozano-Rojas, F., Schmutte, I., Simon, K., Weinberg, B. A., & Wing, C. (2022). Determinants of disparities in early COVID-19 job losses. Demography, 59(3), 827–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J. H., & Lee, R. H. (2020). Is the COVID-19’s impact equal to all in South Korea?-Focusing on the effects on income and poverty by employment status. Korean Journal of Social Welfare, 72(4), 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nella, D., Panagopoulou, E., Galanis, N., Montgomery, A., & Benos, A. (2015). Consequences of job insecurity on the psychological and physical health of greek civil servants. BioMed Research International, 2015, 673623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E. J., Min, H. J., & Kim, J. H. (2009). Career Choice and Labor Market Transition of the Married Women by Level of Education. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 12(1), 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. E., & Kim, H. S. (2020). Part-time work and marriage satisfaction among women in dual-income families: Focusing on the mediating effects of the division of household labor. Korean Journal of Family Social Work, 67(4), 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y. R. (2022). Analysis of factors influencing job change for married working women with COVID-19. Journal of Asian Women, 61(2), 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J., & Lee, E. A. (2004). Work-family experiences and vocational consciousness of married women. Journal of Korean Women’s Studies, 20(2), 141–178. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. S., & Ra, D. S. (2009). A comparative study on factors relate with job acquisition between married and single mothers. Social Welfare Policy, 36(4), 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K. N. (2009). A study on the factors affecting time conflict of married women workers between work and family: Focusing on the differences according to age groups and gender role attitudes. Journal of Korean Women’s Studies, 25(2), 37–71. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. H., & Lee, J. E. (2021). A difference in life satisfaction of married women by income class and the employment status. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 12(3), 2121–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, F. D., Kumalasari, A. D., Novianti, L. E., Kendhawati, L., Noer, A. H., & Ninin, R. H. (2021). Marriage and quality of life during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0256643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remery, C., Petts, R. J., Schippers, J., & Yerkes, M. A. (2022). Gender and employment: Recalibrating women’s position in work, organizations, and society in times of COVID-19. Gender, Work and Organization 29, 1927–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Ruppanner, L., Moller, S., & Sayer, L. (2019). Expensive childcare and short school days= lower maternal employment and more time in childcare? Evidence from the American time use survey. Socius, 5, 2378023119860277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, H., & Chaudry, A. (2012). ‘You have to choose your childcare to fit your work’: Childcare decision-making among low-income working families. Journal of Children and Poverty, 18(2), 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J. O., & Kim, H. L. (2021). A qualitative study of intention of additional childbirth and perceived parental efficacy within married-womens experience of work/family reconciliation. Journal of Asian Women, 60(2), 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. (2023). Microdata integrated service. Available online: https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/index.do (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Sudo, N. (2017). The effects of women’s labor force participation: An explanation of changes in household income inequality. Social Forces, 95(4), 1427–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S., Couto, E. B., & Francisco, P. M. (2016). Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. Journal of Management & Governance, 20(3), 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. J. (2013). Women’s economic participation, determinants, and effects. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 215, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S. W., & Park, N. R. (2024). Development of work-life/family policy and gendered division of childcare responsibility: The case of South Korea. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 44(1/2), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | Low Income | Middle Income | Upper Income | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 1078 | 100.0 | 5420 | 100.0 | 3976 | 100.0 | 10,474 | 100.0 | ||

| Personal factors | Age | Mean (SD) | 65.42 | (13.078) | 54.16 | (13.684) | 50.23 | (11.114) | 53.83 | (13.422) |

| Under age 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 20–29 | 9 | 0.8 | 95 | 1.8 | 104 | 2.6 | 208 | 2 | ||

| 30–39 | 53 | 4.9 | 810 | 14.9 | 646 | 16.2 | 1509 | 14.4 | ||

| 40–49 | 72 | 6.7 | 1306 | 24.1 | 1085 | 27.3 | 2463 | 23.5 | ||

| 50–59 | 146 | 13.5 | 1062 | 19.6 | 1305 | 32.8 | 2513 | 24 | ||

| Age 60 or older | 798 | 74.0 | 2147 | 39.6 | 835 | 21.0 | 3780 | 36.1 | ||

| Education | Unschooled | 108 | 10 | 100 | 1.8 | 7 | 0.2 | 215 | 2.1 | |

| Elementary school | 382 | 35.4 | 725 | 13.4 | 149 | 3.7 | 1256 | 12 | ||

| Middle school | 205 | 19 | 744 | 13.7 | 225 | 5.7 | 1174 | 11.2 | ||

| High school | 251 | 23.3 | 1900 | 35.1 | 1345 | 33.8 | 3496 | 33.4 | ||

| College (less than 4 years) | 65 | 6 | 932 | 17.2 | 725 | 18.2 | 1722 | 16.4 | ||

| University (4+ years) | 56 | 5.2 | 894 | 16.5 | 1189 | 29.9 | 2139 | 20.4 | ||

| Master’s program | 11 | 1 | 109 | 2 | 279 | 7 | 399 | 3.8 | ||

| Doctoral program | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0.3 | 57 | 1.4 | 73 | 0.7 | ||

| Household income | Less than 1 million won | 779 | 72.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 779 | 7.4 | |

| Less than 2 million won | 299 | 27.7 | 1216 | 22.4 | 0 | 0 | 1515 | 14.5 | ||

| Less than 3 million won | 0 | 0 | 1685 | 31.1 | 0 | 0 | 1685 | 16.1 | ||

| Less than 4 million won | 0 | 0 | 1061 | 19.6 | 701 | 17.6 | 1762 | 16.8 | ||

| Less than 5 million won | 0 | 0 | 974 | 18 | 465 | 11.7 | 1439 | 13.7 | ||

| Less than 6 million won | 0 | 0 | 484 | 8.9 | 684 | 17.2 | 1168 | 11.2 | ||

| Less than 7 million won | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 653 | 16.4 | 653 | 6.2 | ||

| Less than 8 million won | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 457 | 11.5 | 457 | 4.4 | ||

| 8 million won and above | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1016 | 25.6 | 1016 | 9.7 | ||

| Location of residence | Dong | 691 | 64.1 | 3885 | 71.7 | 3068 | 77.2 | 7644 | 73 | |

| Eup-myeon | 387 | 35.9 | 1535 | 28.3 | 908 | 22.8 | 2830 | 27 | ||

| Wage earners | Business employees | 63 | 5.8 | 1059 | 19.5 | 1497 | 37.7 | 2619 | 25 | |

| Interim workers | 59 | 5.5 | 453 | 8.4 | 258 | 6.5 | 770 | 7.4 | ||

| Daily laborers | 25 | 2.3 | 121 | 2.2 | 71 | 1.8 | 217 | 2.1 | ||

| Economic activity | Employment | 280 | 26 | 2569 | 47.4 | 2485 | 62.5 | 5334 | 50.9 | |

| Unemployment and economic inactivity | 798 | 74 | 2851 | 52.6 | 1491 | 37.5 | 5140 | 49.1 | ||

| Work from home, whether COVID-19-related | Yes | 22 | 2 | 253 | 4.7 | 482 | 12.1 | 757 | 7.2 | |

| No | 5 | 0.5 | 66 | 1.2 | 86 | 2.2 | 157 | 1.5 | ||

| Housing occupancy type | Own | 801 | 74.3 | 4125 | 76.1 | 3085 | 77.6 | 8011 | 76.5 | |

| Key money | 101 | 9.4 | 613 | 11.3 | 517 | 13 | 1231 | 11.8 | ||

| Monthly rent with deposit | 127 | 11.8 | 534 | 9.9 | 290 | 7.3 | 951 | 9.1 | ||

| Monthly rent without deposit | 11 | 1 | 26 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.4 | 52 | 0.5 | ||

| Free of charge | 38 | 3.5 | 122 | 2.3 | 69 | 1.7 | 229 | 2.2 | ||

| Health assessment | Very good | 36 | 3.3 | 316 | 5.8 | 331 | 8.3 | 683 | 6.5 | |

| Good | 232 | 21.5 | 2054 | 37.9 | 1906 | 47.9 | 4192 | 40 | ||

| Fair | 444 | 41.2 | 2323 | 42.9 | 1485 | 37.3 | 4252 | 40.6 | ||

| Poor | 308 | 28.6 | 678 | 12.5 | 238 | 6 | 1224 | 11.7 | ||

| Very poor | 58 | 5.4 | 49 | 0.9 | 16 | 0.4 | 123 | 1.2 | ||

| Household size | 1 person | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 persons | 679 | 63 | 2156 | 39.8 | 1985 | 49.9 | 4820 | 46 | ||

| 3 persons | 273 | 25.3 | 1383 | 25.5 | 1025 | 25.8 | 2681 | 25.6 | ||

| 4 or more | 126 | 11.7 | 1881 | 34.7 | 966 | 24.3 | 2973 | 28.4 | ||

| Dual income | Dual-income | 6 | 0.6 | 180 | 3.3 | 270 | 6.8 | 456 | 4.4 | |

| Single-income | 57 | 5.3 | 250 | 4.6 | 171 | 4.3 | 478 | 4.6 | ||

| Social and environmental factors | Household division of labor | Wife takes full responsibility | 344 | 31.9 | 1367 | 25.2 | 870 | 21.9 | 2581 | 24.6 |

| Wife primarily handles, husband contributes | 476 | 44.2 | 2929 | 54 | 2118 | 53.3 | 5523 | 52.7 | ||

| Shared responsibilities | 195 | 18.1 | 952 | 17.6 | 867 | 21.8 | 2014 | 19.2 | ||

| Husband primarily handles, wife contributes | 50 | 4.6 | 151 | 2.8 | 99 | 2.5 | 300 | 2.9 | ||

| Husband takes full responsibility | 13 | 1.2 | 20 | 0.4 | 21 | 0.5 | 54 | 0.5 | ||

| Student child | Yes | 122 | 11.3 | 1906 | 35.2 | 1347 | 33.9 | 3375 | 32.2 | |

| No | 956 | 88.7 | 3514 | 64.8 | 2629 | 66.1 | 7099 | 67.8 | ||

| Cohabitation with parents | Living together | 12 | 1.1 | 82 | 1.5 | 57 | 1.4 | 151 | 1.4 | |

| Not living together | 261 | 24.2 | 2853 | 52.6 | 2745 | 69 | 5859 | 55.9 | ||

| Category | Low Income | Middle Income | Upper Income | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Attainment satisfaction | Not employed | 2.97 | 0.812 | 2.78 | 0.836 | 2.48 | 0.862 |

| Employed | 3.05 | 0.903 | 2.79 | 0.848 | 2.52 | 0.870 | |

| t-value | −1.287 | −0.249 | −1.278 | ||||

| Family relationship satisfaction | Not employed | 2.27 | 0.820 | 2.26 | 0.803 | 2.10 | 0.786 |

| Employed | 2.41 | 0.767 | 2.23 | 0.807 | 2.17 | 0.813 | |

| t-value | −2.505 * | 1.274 | −2.539 ** | ||||

| Subjective satisfaction | Not employed | 2.90 | 0.785 | 2.68 | 0.885 | 2.34 | 0.865 |

| Employed | 2.96 | 0.915 | 2.64 | 0.874 | 2.33 | 0.902 | |

| t-value | −1.076 | 1.558 | 0.359 | ||||

| Low Income | Middle Income | Upper Income | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E | Wald | Exp (β) | B | S.E | Wald | Exp (β) | B | S.E | Wald | Exp (β) | |

| Age | 0.019 | 0.017 | 1.214 | 1.019 | 0.029 | 0.005 | 38.503 *** | 1.030 | −0.013 | 0.005 | 7.224 ** | 0.987 |

| Education | −0.141 | 0.132 | 1.134 | 0.869 | −0.007 | 0.040 | 0.031 | 0.993 | −0.036 | 0.040 | 0.817 | 0.965 |

| Household income | 0.871 | 0.369 | 5.583 * | 2.389 | 0.236 | 0.043 | 30.422 *** | 1.266 | 0.167 | 0.030 | 30.176 *** | 1.182 |

| Location of residence | −1.016 | 0.300 | 11.463 *** | 0.362 | −0.531 | 0.092 | 33.258 *** | 0.588 | −0.455 | 0.107 | 18.114 *** | 0.634 |

| Housing occupancy type | −0.049 | 0.130 | 0.145 | 0.952 | −0.003 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.997 | 0.002 | 0.052 | 0.001 | 1.002 |

| Health assessment | 0.004 | 0.174 | 0.001 | 1.004 | 0.107 | 0.052 | 4.188 * | 0.899 | −0.031 | 0.057 | 0.297 | 0.969 |

| Household size | 0.118 | 0.261 | 0.204 | 1.125 | −0.202 | 0.073 | 7.581 ** | 0.817 | −0.125 | 0.070 | 3.144 | 0.883 |

| Household division of labor | 0.120 | 0.173 | 0.478 | 1.127 | 0.355 | 0.054 | 43.292 *** | 1.426 | 0.521 | 0.059 | 77.489 *** | 1.683 |

| Student child | 0.783 | 0.343 | 5.207 * | 2.188 | 0.359 | 0.094 | 14.756 *** | 1.433 | 0.052 | 0.101 | 0.259 | 1.053 |

| Cohabitation with parents | 0.505 | 0.627 | 0.648 | 1.657 | 0.580 | 0.243 | 5.697 * | 1.786 | 0.172 | 0.299 | 0.330 | 1.187 |

| Number of cases = 1078 χ2 = 35.234 Nagelkerke R2 = 0.166 | Number of cases = 5420 χ2 = 162.218 Nagelkerke R2 = 0.072 | Number of cases = 1871 χ2 = 551.21 Nagelkerke R2 = 0.342 | ||||||||||

| Variable | Age | Education | Household Income | Location of Residence | Housing Occupancy Type | Health Assessment | Household Size | Household Division of Labor | Student Child | Cohabitation with Parents | Attainment Satisfaction | Family Relationship Satisfaction | Subjective Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Education | −0.637 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Household income | −0.436 ** | 0.510 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Location of residence | −0.143 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.158 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Housing occupancy type | −0.150 ** | 0.066 ** | −0.049 ** | 0.045 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Health assessment | 0.339 ** | −0.331 ** | −0.254 ** | −0.031 ** | −0.009 | 1 | |||||||

| Household size | −0.469 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.021 * | −0.152 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Household division of labor | −0.141 ** | 0.117 ** | 0.040 ** | 0.037 ** | 0.056 ** | −0.041 ** | −0.006 | 1 | |||||

| Student child | −0.448 ** | 0.372 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.103 ** | 0.026 ** | −0.157 ** | 0.607 ** | −0.022 * | 1 | ||||

| Cohabitation with parents | 0.037 ** | −0.005 | 0.011 | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.012 | 0.089 ** | −0.003 | −0.020 | 1 | |||

| Attainment satisfaction | 0.067 ** | −0.162 ** | −0.217 ** | 0.005 | 0.094 ** | 0.338 ** | −0.023 * | −0.053 ** | −0.037 ** | 0.006 | 1 | ||

| Family Relationship satisfaction | 0.160 ** | −0.145 ** | −0.120 ** | 0.011 | −0.007 | 0.227 ** | −0.051 ** | −0.127 ** | −0.051 ** | 0.006 | 0.288 ** | 1 | |

| Subjective satisfaction | 0.130 ** | −0.222 ** | −0.247 ** | −0.014 | 0.074 ** | 0.390 ** | −0.055 ** | −0.055 ** | −0.074 ** | −0.001 | 0.650 ** | 0.329 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cha, Y.-J. Analysis of Economic Activity Participation and Determining Factors Among Married Women by Income Level After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040399

Cha Y-J. Analysis of Economic Activity Participation and Determining Factors Among Married Women by Income Level After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040399

Chicago/Turabian StyleCha, Yu-Jin. 2025. "Analysis of Economic Activity Participation and Determining Factors Among Married Women by Income Level After the COVID-19 Pandemic" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040399

APA StyleCha, Y.-J. (2025). Analysis of Economic Activity Participation and Determining Factors Among Married Women by Income Level After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040399