Predictors of Expectations for the Future Among Young Korean Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Hypotheses

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participants’ Characteristics

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. Stress (Perceived Stress Scale, PSS-10)

2.5.2. Depression (SU Mental Health Test Subscale)

2.5.3. Gratitude (Gratitude Questionnaire-6, GQ-6)

2.5.4. Hardiness (Brief Measure of Hardiness, BMH)

2.5.5. Interpersonal Competence (SU Mental Health Test Subscale)

2.5.6. Social Support (Social Support Scale)

2.5.7. Expectations for the Future (Life Satisfaction Expectancy Scale)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Relationships Between the Variables Involved in This Study

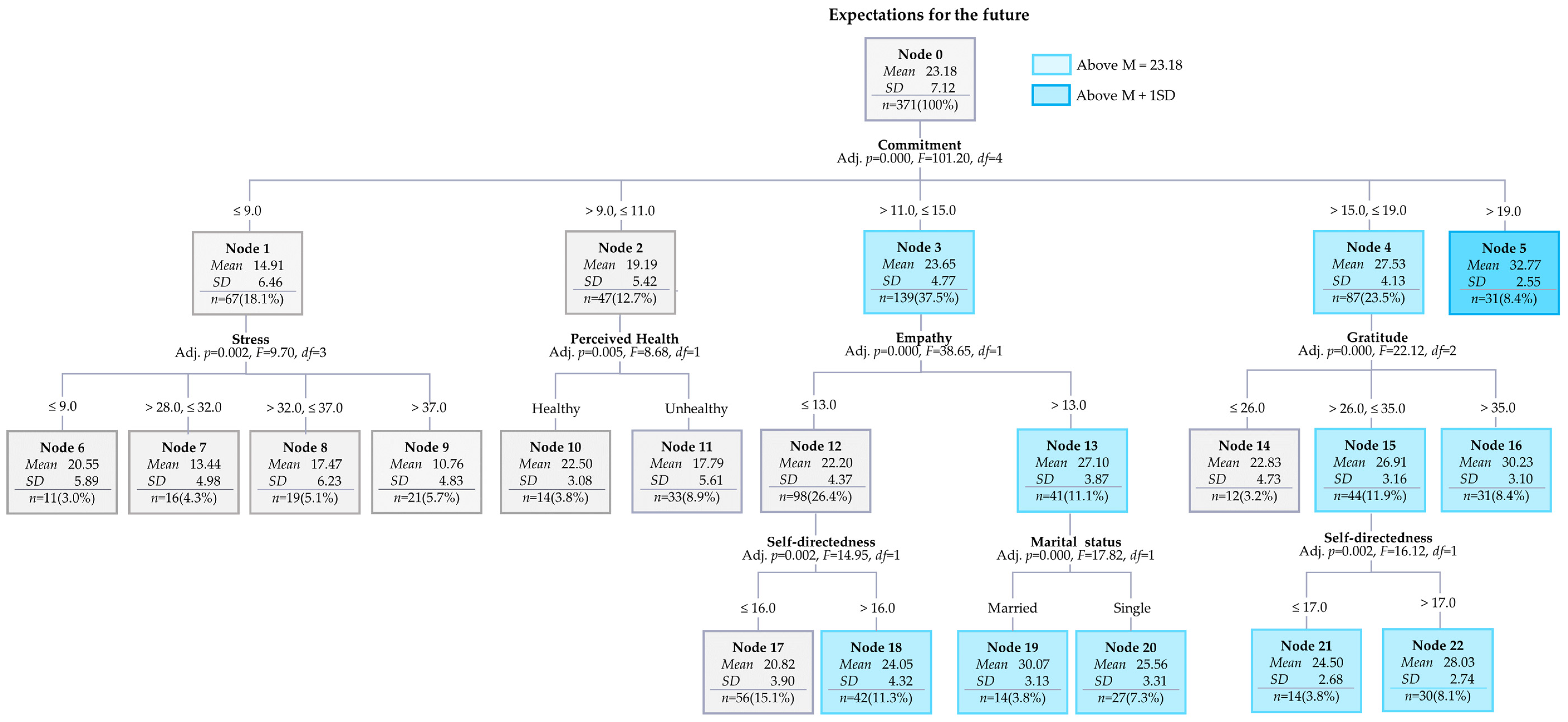

3.2. Predictive Models for Expectations for the Future

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSS | Perceived stress scale |

| CHAID | chi-square automatic interaction detection |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

References

- Ahn, S. (2021). An analysis of the structural model of social support, problem solving ability, interpersonal relations, and future life expectation of outdoor sports participation. Journal of Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 21(8), 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C., & Bellebaum, C. (2021). Effects of trait empathy and expectation on the processing of observed actions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 21, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Deuri, S. P., Deuri, S. K., Jahan, M., Singh, A. R., & Verma, A. N. (2010). Perceived social support and life satisfaction in persons with somatization disorder. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 19(2), 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkozei, A., Smith, R., & Killgore, W. D. S. (2018). Gratitude and subjective wellbeing: A proposal of two causal frameworks. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(5), 1519–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L. R., McNulty, J. K., & VanderDrift, L. E. (2017). Expectations for future relationship satisfaction: Unique sources and critical implications for commitment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(5), 700721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P. T. (1999). Hardiness protects against war-related stress in Army reserve forces. Consulting Psychology Journal, 51(2), 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1987). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan, & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doktorova, D., Hubinská, J., & Masár, M. (2020). Finding the connection between the level of empathy, life satisfaction and their inter-sex differences. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R., Wierenga, A., & Wyn, J. (2005). Life in a time of uncertainty: Optimising the health and wellbeing of young Australians. The Medical Journal of Australia, 183(8), 402−404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschleman, K. J., Bowling, N. A., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of hardiness. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(4), 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A. M., Bryce, C. I., Cahill, K. M., & Jenkins, D. L. (2024). Social support and positive future expectations, hope, and achievement among Latinx students: Implications by gender and special education. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 41(3), 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Fives, C. J., Fuller, J. R., Jacofsky, M. D., Terjesen, M. D., & Yurkewicz, C. (2007). Interpersonal relationships and irrationality as predictors of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigaitytė, I., & Söderberg, P. (2021). Why does perceived social support protect against somatic symptoms: Investigating the roles of emotional self-efficacy and depressive symptoms? Nordic Psychology, 73(3), 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. A., Dominguez, J., & Mihailova, T. (2023). Interpersonal media and face-to-face communication: Relationship with life satisfaction and loneliness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovu, M. B., Hărăguș, P. T., & Roth, M. (2018). Constructing future expectations in adolescence: Relation to individual characteristics and ecological assets in family and friends. Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(1), 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R. D., Olekalns, M., & Erwin, P. J. (1998). Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 52(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, E. (2010). Perceived social support and life-satisfaction. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 41(4), 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, G. V. (1980). An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Applied Statistics, 29(2), 119−127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, A., & Melis, G. (2022). Youth attitudes towards their future: The role of resources, agency and, individualism in the UK. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 5(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2007). The relationship between life satisfaction/life satisfaction expectancy and stress/well-being: An application of Motivational States Theory. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 12(2), 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. G., & Kim, H. Y. (2013). A study on adolescents’ expectation of future: Focused on self-esteem and social support. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association, 51(2), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, M. (2023). A study on youth employment policy and youth’s life satisfaction: Focusing on experience of employment success package. Journal of Humanity and Social Science, 14(1), 25−40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kobasa, S. C. (1979). Personality and resistance to illness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 7(4), 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komase, Y., Watanabe, K., Hori, D., Nozawa, K., Hidaka, Y., Iida, M., Imamura, K., & Kawakami, N. (2021). Effects of gratitude intervention on mental health and well-being among workers: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraftl, P. (2008). Young people, hope, and childhood-hope. Space and Culture, 11(2), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. J., Kim, K. H., & Lee, H. S. (2006). Validation of the Korean version of gratitude questionnaire. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 11(1), 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, M. E. (2001). Adult development, psychology of. In N. J. Smelser, & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 135–139). Pergamon. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., & Jeon, H. (2011). Effects of life satisfaction expectancy, mindfulness and social support on depression of the marital middle-aged women. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 11(7), 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Shin, C., Ko, Y., Lim, J., Joe, S., Kim, S., Jung, I., & Han, C. (2012). The reliability and validity studies of the Korean version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Korean Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine, 20(2), 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani-Benito, O., Carranza, E. R. F., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Castillo-Blanco, R., Tito-Betancur, M., Alfaro, V. R., & Ruiz, M. P. G. (2023). The influence of self-esteem, depression, and life satisfaction on the future expectations of Peruvian university students. Frontiers in Education, 8, e976906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigal, K. (2015). The upside of stress: Why stress is good for you, and how to get good at it. Avery. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski, K. N. (2011). Unfulfilled expectations and symptoms of depression among young adults. Social Science & Medicine, 73(5), 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, Y. (2011). The effect of job stress of regional government employees on job satisfaction and organizational commitment: Focused on adjustment · prevention · solution effects according to social support [Unpublished Master’s Thesis, The Catholic University of Korea]. [Google Scholar]

- Park, A. (2023). ADHD trait, emotional music use, and expectation for future life in early adolescence: Focused on mediating effect of relationship initiation. Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 21(6), 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A., & Suh, K. (2023). Hardiness and expectations for future life: The roles of perceived stress, music listening for negative emotion regulation, and life satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N. (2023). A study on the reproduction of family in recent Korean cartoons: Focusing on the crisis of normal family and the reproduction of various forms of family. Cartoon & Animation Studies, 70, 247−280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. W., & Jin, S. (2019). An alternative approach toward better futures for the young generation: Focusing on work, housing, and relationship of singles in their 30s. Journal of Korean Social Trend and Perspective, 106, 67−110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, A., & Sobol-Kwapinska, M. (2021). People with positive time perspective are more grateful and happier: Gratitude mediates the relationship between time perspective and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(1), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2016). Expectation-focused psychological interventions (EFPI). Verhaltenstherapie, 26(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanciogullari, S., Tuncay, F. O., & Avci, D. (2016). The relationship between life satisfaction and perceived health and sexuality in individuals diagnosed with a physical illness. Sexuality and Disability, 34(4), 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom-Daly, U. M., Peate, M., Wakefield, C. E., Bryant, R. A., & Cohn, R. J. (2012). A systematic review of psychological interventions for adolescents and young adults living with chronic illness. Health Psychology, 31(3), 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwick, S. M., Vythilingam, M., & Charney, D. S. (2005). The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: Implications for prevention and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 255–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K. (2022). Development and validation of a brief measure of hardiness for the Korean population. Stress, 30(2), 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K., Lee, H., & Bartone, P. T. (2021a). Validation of Korean version of the hardiness resilience gauge. Sustainability, 13(24), 13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K., Lee, H., Kim, K., & Moon, T. (2021b). Development and standardization of SU mental health test. Sahmyook University. [Google Scholar]

- Syropoulos, S., & Markowitz, E. M. (2021). A grateful eye towards the future? Dispositional gratitude relates to consideration of future consequences. Personality and Individual Differences, 179, e110911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In M. S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhauer, J. S., Young, S., Kealoha, C., & Borrayo, E. A. (2012). Treating major depression by creating positive expectations for the future: A pilot study for the effectiveness of future-directed therapy (FDT). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 18(2), 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N., Ding, F., Zhang, R., Cai, Y., & Zhang, H. (2022). The relationship between perceived social support and life satisfaction: The chain mediating effect of resilience and depression among Chinese medical staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağar, S. D., & Yağar, F. (2023). The impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction and moderating role of social support: A study in COVID-19 normalization process. Educational Gerontology, 49(8), 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetsche, U., Bürkner, P. C., & Renneberg, B. (2019). Future expectations in clinical depression: Biased or realistic? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(7), 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Man | 181 | 48.8 |

| Woman | 190 | 51.2 |

| Age | ||

| 20s | 187 | 50.4 |

| 30s | 184 | 49.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Having religion | 96 | 25.9 |

| None | 275 | 74.1 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school | 63 | 17.0 |

| College | 278 | 74.9 |

| Graduate school | 30 | 8.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 92 | 26.2 |

| Single | 272 | 73.3 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.5 |

| Presence of children | ||

| Having a child | 58 | 15.6 |

| None | 313 | 84.4 |

| Housing type | ||

| Living alone | 89 | 24.0 |

| Living with other(s) | 282 | 76.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Having a job | 266 | 71.7 |

| None | 105 | 28.3 |

| Presence of disease | ||

| Having a disease | 50 | 13.5 |

| None | 321 | 86.5 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stress | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Depression | 0.69 *** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Gratitude | −0.47 *** | −0.66 *** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Hardiness | −0.51 *** | −0.61 *** | 0.69 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Interpersonal competence | −0.35 *** | −0.42 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.65 *** | 1 | ||

| 6. Social support | −0.44 *** | −0.59 *** | 0.70 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.58 *** | 1 | |

| 7. Expectations for the future | −0.56 *** | −0.66 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.59 *** | 1 |

| M | 29.87 | 27.81 | 29.04 | 47.53 | 23.39 | 27.85 | 23.18 |

| SD | 5.62 | 12.01 | 6.94 | 9.67 | 5.36 | 6.15 | 7.12 |

| Skewness | 0.13 | 0.36 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.12 | −0.48 |

| Kurtosis | 0.44 | −0.66 | −0.37 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.25 | −0.20 |

| Variables | B | β | t | ∆R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment | 1.190 | 0.732 | 20.61 *** | 0.535 | 146.04 *** |

| Gratitude | 0.382 | 0.372 | 8.87 *** | 0.082 | |

| Self-directedness | 0.374 | 0.187 | 5.10 *** | 0.025 | |

| Depression | −0.117 | −0.197 | −4.57 *** | 0.020 | |

| Having a disease | 1.531 | −0.073 | −2.37 * | 0.005 |

| Nodes | N | % | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 31 | 8.4 | 32.77 |

| 16 | 31 | 8.4 | 30.23 |

| 19 | 14 | 3.8 | 30.07 |

| 22 | 30 | 8.1 | 28.03 |

| 20 | 27 | 7.3 | 25.56 |

| 21 | 14 | 3.8 | 24.50 |

| 18 | 42 | 11.3 | 24.05 |

| 14 | 12 | 3.2 | 22.83 |

| 10 | 14 | 3.8 | 22.50 |

| 17 | 56 | 15.1 | 20.82 |

| 6 | 11 | 3.0 | 20.55 |

| 11 | 33 | 8.9 | 17.79 |

| 8 | 19 | 5.1 | 17.47 |

| 7 | 16 | 4.3 | 13.44 |

| 9 | 21 | 5.7 | 10.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, J.-S.; Suh, K.-H. Predictors of Expectations for the Future Among Young Korean Adults. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030391

An J-S, Suh K-H. Predictors of Expectations for the Future Among Young Korean Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030391

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Jae-Sun, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2025. "Predictors of Expectations for the Future Among Young Korean Adults" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030391

APA StyleAn, J.-S., & Suh, K.-H. (2025). Predictors of Expectations for the Future Among Young Korean Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030391