Macropsychology: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Psychology Literature on Public Policy and Law

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Aim

“[T]he law is not an inanimate rule book for some inherently fair or meritocratic game of individual chance, skill, or even ‘justice’. It can be a powerful engine for the progressive advancement of some or all people or the means of their repression. It is made by humans and so is never completely neutral. It has moral content and values, not only in its substance but in its linguistic framing, form, process, and priorities”.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

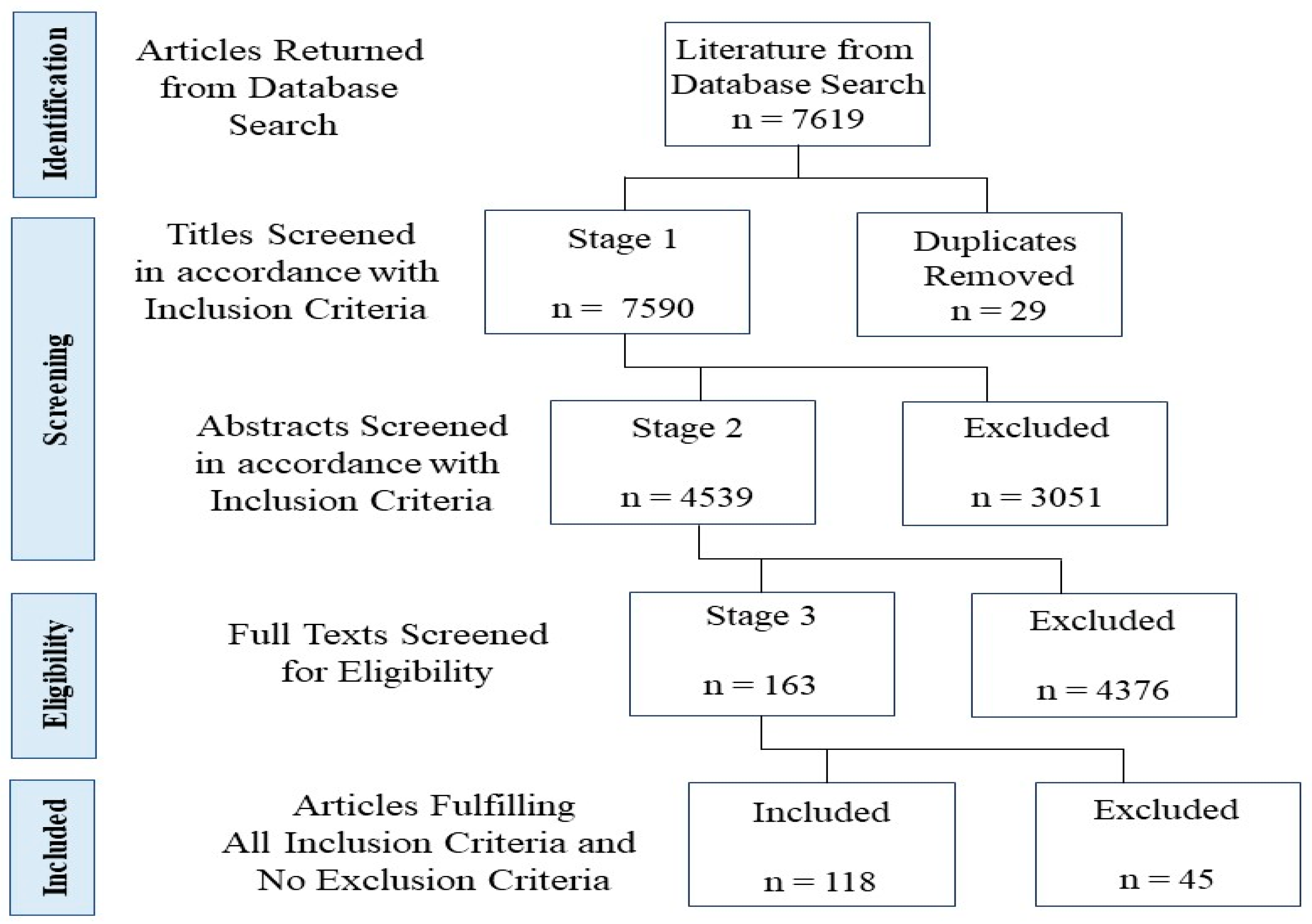

2.2. Literature Screening

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Populations

3.1.1. Children and Adolescents

3.1.2. People with Mental Health Problems

3.1.3. LGBTQ+ Persons

3.1.4. Miscellaneous Populations

3.2. Age, Gender, and Ethnicity

3.3. Type of Article and Method

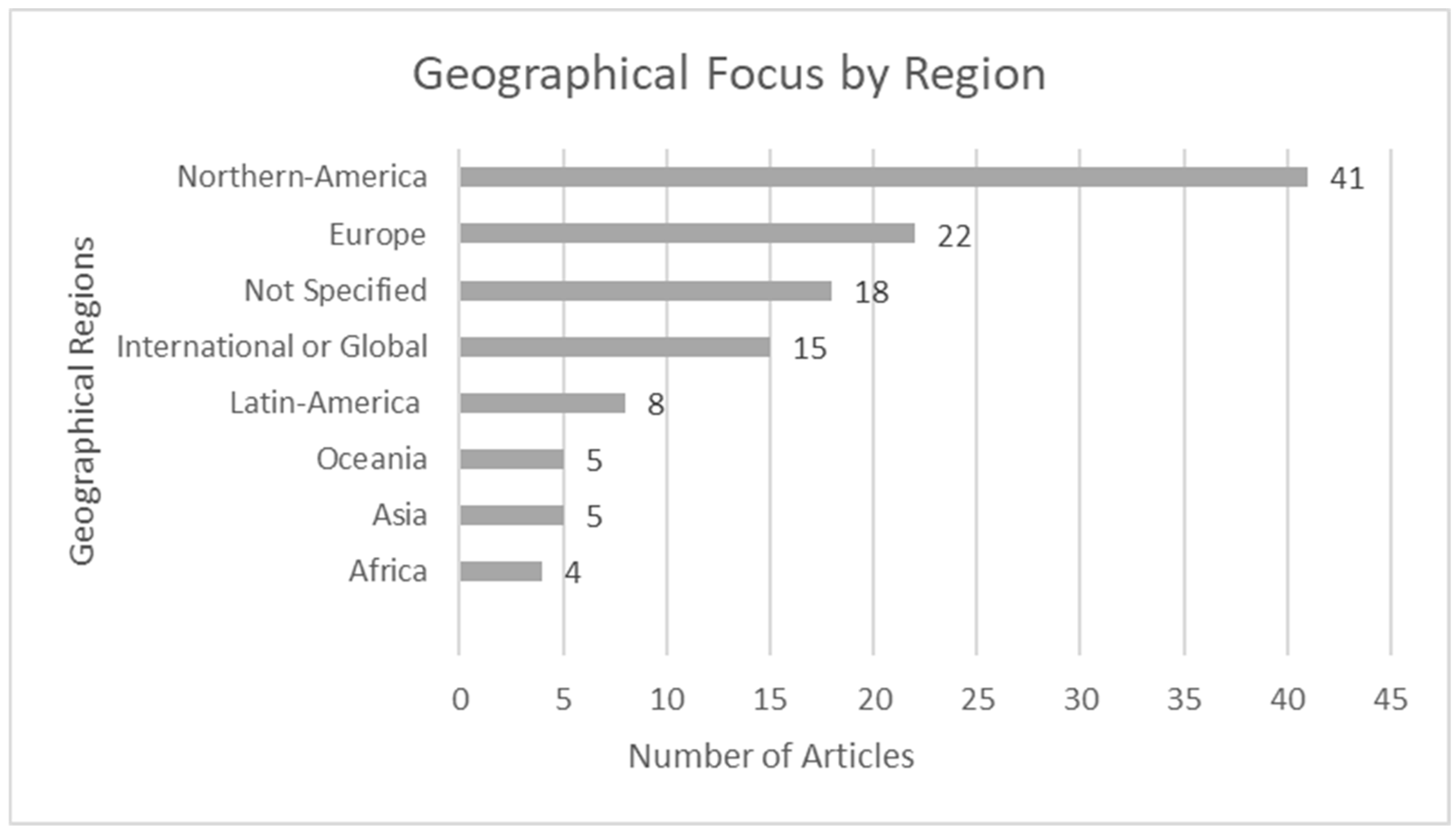

3.4. Geographical Location

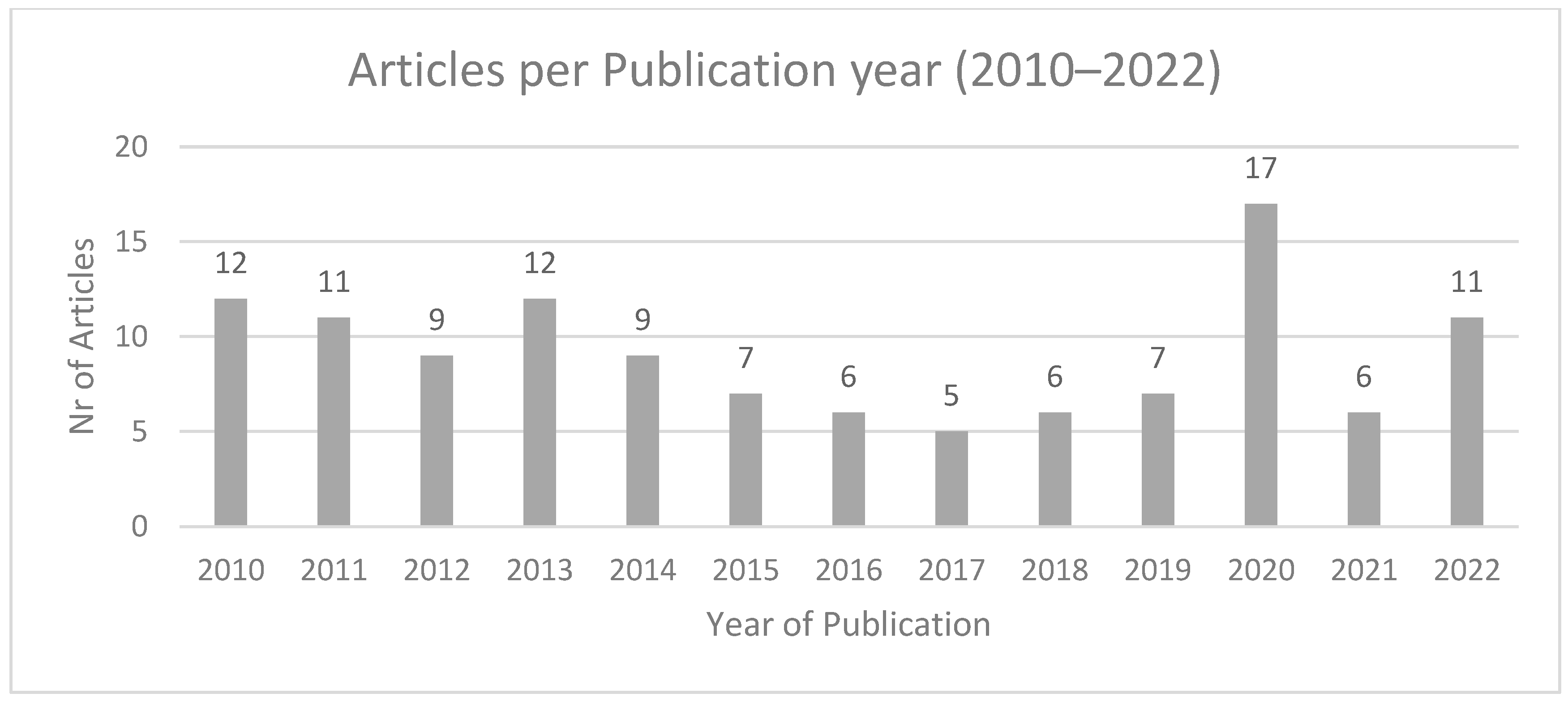

3.5. Year of Publication

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abreu, R. L., Sostre, J. P., Gonzalez, K. A., Lockett, G. M., & Matsuno, E. (2021). ‘I am afraid for those kids who might find death preferable’: Parental figures’ reactions and coping strategies to bans on gender affirming care for transgender and gender diverse youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(4), 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R. L., Sostre, J. P., Gonzalez, K. A., Lockett, G. M., Matsuno, E., & Mosley, D. V. (2022). Impact of gender-affirming care bans on transgender and gender diverse youth: Parental figures’ perspective. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(5), 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrusti, T., Bohn, J., Dunn, E., Bell, C., & Ziegler, A. (2020). The story so far: A mixed-methods evaluation of county-level behavioral health needs, policies, and programs. Social Work in Mental Health, 18(3), 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, J., & Martin, M. P. (2015). Proceso y oportunidades de la transferencia del conocimiento desde la psicología comunitaria a las políticas públicas = Process and opportunities for knowledge transfer from community psychology to public policy. Universitas Psychologica, 14(4), 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrawis, A., Tapa, J., Vlaev, I., Read, D., Schmidtke, K. A., Chow, E. P. F., Lee, D., Fairley, C. K., & Ong, J. J. (2022). Applying behavioural insights to HIV prevention and management: A scoping review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 19, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, R. (2016). Living in the shadows: Plight of the undocumented. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(8), 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. J. L., & Brassard, M. (2019). Predictors of variation in sate reported rates of psychological maltreatment: A survey of statutes and a call for change. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Rojas, M. A., & Baeza Ruiz, A. (2021). La salud mental como derecho humano en Quintana Roo, México Análisis desde la disciplina de la política pública = Mental health as a human right in Quintana Roo, Mexico Analysis from the discipline of public policy. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 38(3), 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battams, S., & Henderson, J. (2012). The right to health, international human rights legislation and mental health policy and care practices for people with psychiatric disability. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 19(3), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendat, M. (2014). In name only? Mental health parity or illusory reform. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 42(3), 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelli, S. J. (2016). Risco e vulnerabilidade como analisadores nas políticas públicas sociais: Uma análise crítica = Risk and vulnerability as criteria to evaluate social and public policies: A critical analysis. Estudos de Psicologia, 33(4), 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielsa, V. C., Braddick, F., Jané-Llopis, E., Jenkins, R., & Puras, D. (2010). Child and adolescent mental health policies, programmes and infrastructures across Europe. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 12(4), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerge, B., Christensen, L., & Oute, J. (2020). Complex cases—Complex representations of problems. International Journal of Drug Policy, 80, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, M. B. J. (2010). Disability, social policy and the burden of disease: Creating an ‘assertive’ community mental health system in New York. Psychology, 1(2), 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl. S2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, S. L., Neal, T. M. S., & Jones, M. A. (2013). A reasoned argument against banning psychologists’ involvement in death penalty cases. Ethics & Behavior, 23(1), 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, N., Zlotowitz, S., Alcock, K., & Barker, C. (2020). Practice to policy: Clinical psychologists’ experiences of macrolevel work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(4), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, M., Hofgaard, T. L., Benito, E., Flattau, P., Clinton, A., Shealy, C., & Kapadia, S. (2023). Policy: Why and how to become engaged as an international policy psychologist. In C. Shealy, M. Bullock, & S. Kapadia (Eds.), Going global: How psychologists can meet a world of need (pp. 121–142). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, J. E. M., Fellin, L. C., & Warner-Gale, F. (2017). A critical analysis of child and adolescent mental health services policy in England. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(1), 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E. J., & Steel, E. J. (2015). Mental distress and human rights of asylum seekers. Journal of Public Mental Health, 14(2), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew, D., Birkin, R., & Booth, D. (2010). Employment, policy and social inclusion. The Psychologist, 23(1), 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S. C., & MacLachlan, M. (2014). Humanitarian work psychology. The Psychologist, 27(3), 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, E., & Taggart, L. (2012). England and Northern Ireland policy and law update relating to mental health and intellectual disability. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 6(3), 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. (2020). Improvement of mental health of labourers through the publicity of social security law. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(2), 692–697. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, B., & Kapadia, S. (2023). Mental health policies in queer community: Are we doing enough? Journal of Loss and Trauma, 28, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, D. J., & Montiel, C. J. (2013). Contributions of psychology to war and peace. American Psychologist, 68(7), 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. N., & Roesch, R. (2012). ‘Tough on crime’ reforms: What psychology has to say about the recent and proposed justice policy in Canada. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 53(3), 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, L., Mills, C., Karter, J. M., Mehta, A., & Kalathil, J. (2020a). A critical review of the Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development: Time for a paradigm change. Critical Public Health, 30(5), 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, L., Morrill, Z., Karter, J. M., Valdes, E., & Cheng, C.-P. (2020b). The cultural politics of mental illness: Toward a rights-based approach to global mental health. Community Mental Health Journal, 57, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, S., Banks, D., Crawshaw, P., & Clifton, A. (2011). Mental health service user involvement in policy development: Social inclusion or disempowerment? Mental Health Review Journal, 16(4), 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., Côté, G., Latimer, E. A., & Seto, M. C. (2010). Individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder: Are we providing equal protection and equivalent access to mental health services across Canada? Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 29(2), 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, T., Gouda, P., McDonald, C., & Hallahan, B. (2017). A comparison of mental health legislation in five developed countries: A narrative review. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 34(4), 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B. (2019). Mental health trauma treatment within the current Mediterranean refugee crisis. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 41(4), 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E., Crothers, C., & Hanna, K. (2010). Preventing child poverty: Barriers and solutions. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 39(2), 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer, J. L., Allouche, S. F., Vasquez, J. I., & Rhodes, J. (2022). Equitable practices in school mental health. Psychology in the Schools, 59, 1222–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fátima Guareschi, N. M., de Lara, L., & Adegas, M. A. (2010). Políticas públicas entre o sujeito de direitos e o homo œconomicus = Social psychology and public policies: Between the subject’s rights and the homo œconomicus. Psico, 41(3), 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas, C., García-Ramirez, M., Aambø, A., & Buttigieg, S. C. (2014). Transforming health policies through migrant user involvement: Lessons learnt from three European countries. Psychosocial Intervention, 23(2), 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, D. F., Fern Jesus, M., Ferreira, P. D., Coimbra, S., Teixeira, P. M., de Moura, A., Gato, J., Marques, S. C., & Fontaine, A. M. (2018). Psychological correlates of perceived ethnic discrimination in Europe: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Peña, C. M., Pineda, L., & Punsky, B. (2019). Working with parents and children separated at the border: Examining the impact of the zero tolerance policy and beyond. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(2), 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (Ireland). (2015). Report of the expert group review of the Mental Health Act, 2001. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/637ccf-report-of-the-expert-group-review-of-the-mental-health-act-2001/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Dopp, A. R., & Lantz, P. M. (2020). Moving upstream to improve children’s mental health through community and policy change. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(5), 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F. J., Pickett, W., Pförtner, T.-K., Gariépy, G., Gordon, D., Georgiades, K., Davison, C., Hammami, N., MacNeil, A. H., Da Silva, M. A., & Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. (2021). Relative food insecurity, mental health and wellbeing in 160 countries. Social Science & Medicine, 268, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H., & Russell-Mayhew, S. (2020). The responsibility of Canadian counselling psychology to reach systems, organizations, and policy-makers. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 54(4), 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M. (2013). Echoes of Bedford: A 20-year social psychology memoir on participatory action research hatched behind bars. American Psychologist, 68(8), 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C. B. (2013). Human rights and psychologists’ involvement in assessments related to death penalty cases. Ethics & Behavior, 23(1), 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. R. W., & de Mello, M. C. (2011). Using the World Health Organization’s 4S-Framework to strengthen national strategies, policies and services to address mental health problems in adolescents in resource-constrained settings. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focarelli, C. (2012). International law as social construct: The struggle for global justice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forberger, S., Reisch, L., Kampfmann, T., & Zeeb, H. (2019). Nudging to move: A scoping review of the use of choice architecture interventions to promote physical activity in the general population. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, A. K., Fredén, L., Lindqvist, R., & Wahlbeck, K. (2015). Contribution of the Nordic School of Public Health to the public mental health research field: A selection of research initiatives, 2007–2014. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 43(16), 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedli, L. (2009). Mental health, resilience and inequalities. WHO Europe. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107925 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Fullen, M. C., Wiley, J. D., & Morgan, A. A. (2019). The Medicare mental health coverage gap: How licensed professional counselors navigate Medicare-ineligible provider status. The Professional Counselor, 9(4), 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, M., Drew, N., & Knapp, M. (2012). Mental health, poverty and development. Journal of Public Mental Health, 11(4), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, V., & Pelissari, M. A. (2013). Psicologia e os contextos socio-político-cultural e das políticas sociais no século XXI = Psychology and socio-political-cultural and social policies contexts in the XXI century. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissâo, 33, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vázquez, E., Reddy, L., Arora, P., Crepeau-Hobson, F., Fenning, P., Hatt, C., Hughes, T., Jimerson, S., Malone, C., Minke, K., Radliff, K., Raines, T., Song, S., & Strobach, K. V. (2020). School psychology unified antiracism statement and call to action. School Psychology Review, 49(3), 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, G., Deister, A., Heinz, A., Koller, M., Müller, S., Steinert, T., & Pollmächer, T. (2019). Nach der Reform ist vor der Reform: Ergebnisse der Novellierungsprozesse der Psychisch-Kranken-Hilfe-Gesetze der Bundesländer = After the reform is before the reform: Results of the amendment processes of mental health law in German federal states. Der Nervenarzt, 90(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfoyle, N., & Dvoskin, J. A. (2017). APA’s amicus curiae program: Bringing psychological research to judicial decisions. American Psychologist, 72(8), 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girvan, E., & Marek, H. J. (2016). Psychological and structural bias in civil jury awards. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 8(4), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S. A. (2010). La salud mental a la luz de la Constitución colombiana: Análisis de algunas sentencias de la Corte Constitucional, 1992–2009 = Mental health in the light of the Colombian Constitution: Analysis of some of the sentences of the Constitutional Court, 1992–2009. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 39(3), 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, T., Sewell, H., Shapiro, G., & Ashraf, F. (2013). Mental health inequalities facing UK minority ethnic populations: Causal factors and solutions. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 3, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, P. R., DeVore, E. N., Frantell, K. A., Miles, J. R., & Spengler, E. S. (2020a). Conscience clauses and sexual and gender minority mental health care: A case study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(5), 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, P. R., Spengler, E. S., Miles, J. R., Frantell, K. A., & DeVore, E. N. (2020b). ‘Sincerely held principles’ or prejudice? The Tennessee Counseling Discrimination Law. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(2), 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. C. N., & Yee, A. H. (2012). US mental health policy: Addressing the neglect of Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3(3), 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, M., Egan, M., Rutter, J., & McCrae, J. (2018). Behavioural government: Using behavioural science to improve how governments make decisions. Behavioural Insights Team. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2010). Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4(1), 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Prins, S. J., Flake, M., Philbin, M., Frazer, M. S., Hagen, D., & Hirsch, J. (2017). Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennes, E. P., & Dang, L. (2021). The devil we know: Legal precedent and the preservation of injustice. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(1), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A., Downes, C., O’Sullivan, K., de Vries, J., Molloy, R., Monahan, M., Keogh, B., Doyle, L., Begley, T., & Corcoran, P. (2024). Being LGBTQI+ in Ireland; The national study on the mental health and wellbeing of the LGBTQI+ communities in Ireland. Trinity College. [Google Scholar]

- Javakhishvili, J. D., Ardino, V., Bragesjö, M., Kazlauskas, E., Olff, M., & Schäfer, I. (2020). Trauma-informed responses in addressing public mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Position paper of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1780782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. (2010). Recognition of the nonhuman: The psychological minefield of transgender inequality in the law. Law & Psychology Review, 34, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, L., Boyle, M., Cromby, J., Dillon, J., Harper, D., Kinderman, P., Longden, E., Pilgrim, D., & Read, J. (2018). The power threat meaning framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. British Psychological Society. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/member-networks/division-clinical-psychology/power-threat-meaning-framework (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Jones, R., & Whitehead, M. (2018). ‘Politics done like science’: Critical perspectives on psychological governance and the experimental state. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36(2), 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczkowski, W., Li, J., Cooper, A. C., & Robin, L. (2022). Examining the relationship between LGBTQ-supportive school health policies and practices and psychosocial health outcomes of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual students. LGBT Health, 9(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamody, R. C., Kamody, E. S., Rosenthal, A., & Olezeski, C. L. (2022). Optimizing medical-legal partnerships in pediatric psychology to reduce health disparities. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 47(1), 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M. C., Abreu, R. L., Marchena, M. T., Helpingstine, C., Lopez-Griman, A., & Mathews, B. (2017). Legal and clinical guidelines for making a child maltreatment report. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(6), 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinderman, P. (2021). From chemical imbalance to power imbalance: A macropsychology perspective on mental health. In M. MacLachlan, & J. McVeigh (Eds.), Macropsychology: A population science for sustainable development goals (pp. 29–44). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kinscherff, R. T., & Grisso, T. J. (2013). Human rights violations and Standard 102: Intersections with human rights law and applications in juvenile capital cases. Ethics & Behavior, 23(1), 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitafuna, K. B. (2022). A critical overview of mental health-related beliefs, services and systems in Uganda and recent activist and legal challenges. Community Mental Health Journal, 58, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleintjes, S., Lund, C., & Swartz, L. (2012). South African mental health care service user views on priorities for supporting recovery: Implications for policy and service development. Disability and Rehabilitation: An International, Multidisciplinary Journal, 34(26), 2272–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, S. J., & Fingerhut, R. (2024). Social justice. In S. J. Knapp, & R. Fingerhut (Eds.), Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach (4th ed., pp. 33–42). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgiantakis, T., McNeil, S. R., Hussain, A., Logan, J., Ashcroft, R., Lee, E., & Williams, C. C. (2022). Social work’s approach to recovery in mental health and addiction policies: A scoping review. Social Work in Mental Health, 20, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Költő, A., Vaughan, E., O’Sullivan, L., Kelly, C., Saewyc, E. M., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (2021). LGBTI+ Youth in Ireland and across Europe: A two-phased landscape and research gap analysis. Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth. [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, N. M., Barbee, H., Tran, N. M., Bastow, S., & McKay, T. (2024). Health disparities among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer older adults: A structural competency approach. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 98(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, R., & Williams, A. S. (2011). Linking adults’ problems with children’s pain: Legal, ethical and clinical issues. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 18(2), 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S. E. G. (2021). Debt and overindebtedness: Psychological evidence and its policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 146–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenta, M. M., & Zaldúa, G. (2020). Vulnerabilidad y Exigibilidad de Derechos: La Perspectiva de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes = Vulnerability and rights enforceability: The perspective of children and adolescents. Psykhe: Revista de la Escuela de Psicología, 29(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, L. M., & Manchester, C. F. (2011). Work–family conflict is a social issue not a women’s issue. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 4(3), 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L. M., & Lawrence, S. E. (2022). Weight-based disparities in youth mental health: Scope, social underpinnings, and policy implications. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 9(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Hui, X. (2020). Effect of government policies on mental health of left-behind children. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(2), 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-H., & Peng, K.-P. (2012). Challenge and contribution of cultural psychology to empirical legal studies. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(3), 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C., Kleintjes, S., Cooper, S., Petersen, I., Bhana, A., & Flisher, A. J. (2011). Challenges facing South Africa’s mental health care system: Stakeholders’ perceptions of causes and potential solutions. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 4(1), 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, M. (2014). Macropsychology, policy, and global health. American Psychologist, 69(8), 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, M. (2017). Still too POSH to push for structural change? The need for a macropsychology perspective. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 10(3), 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, M., Amin, M., Mannan, H., El Tayeb, S., Bedri, N., Swartz, L., Munthali, A., Van Rooy, G., & McVeigh, J. (2012). Inclusion and human rights in health policies: Comparative and benchmarking analysis of 51 policies from Malawi, Sudan, South Africa and Namibia. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e35864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLachlan, M., & McVeigh, J. (2021). Macropsychology: Definition, scope and conceptualisation. In M. MacLachlan, & J. McVeigh (Eds.), Macropsychology: A population science for Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 1–27). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, M., McVeigh, J., Huss, T., & Mannan, H. (2019). Macropsychology: Challenging and changing social structures and systems to promote social inclusion. In K. C. O’Doherty, & D. Hodgetts (Eds.), The sage handbook of applied social psychology (pp. 166–182). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Magor-Blatch, L. (2011). Beyond zero tolerance: Providing a framework to promote social justice and healthy adolescent development. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 28(1), 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, L. H. (2018). Mental health news: How frames influence support for policy and civic engagement intentions. Journal of Health Communication, 23(1), 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, H., ElTayeb, S., MacLachlan, M., Amin, M., McVeigh, J., Munthali, A., & Van Rooy, G. (2013). Core concepts of human rights and inclusion of vulnerable groups in the mental health policies of Malawi, Namibia, and Sudan. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 7(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, H., McVeigh, J., Amin, M., MacLachlan, M., Swartz, L., Munthali, A., & VanRooy, G. (2012). Core concepts of human rights and inclusion of vulnerable groups in the disability and rehabilitation policies of Malawi, Namibia, Sudan, and South Africa. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23(2), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. (2017). Social justice, epidemiology and health inequalities. European Journal of Epidemiology, 32, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, K. M., Sechrest, L., & McKnight, P. E. (2005). Psychology, psychologists, and public policy. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J., & MacLachlan, M. (2021). Psychological governance and COVID-19: A case study in macropsychology. In M. MacLachlan, & J. McVeigh (Eds.), Macropsychology—A population science for sustainable development goals. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh, J., & MacLachlan, M. (2022). The macropsychology of COVID-19: Psychological governance as pandemic response. American Psychologist, 77(1), 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J., Mannan, H., Ebuenyi, I. D., & MacLachlan, M. (2024). Inclusive and equitable policies: EquiFrame and EquIPP as frameworks for the analysis of the inclusiveness of policy content and processes. In L. Ned, M. R. Velarde, S. Singh, L. Swartz, & K. Soldatić (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of disability and global health. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Melton, G. B. (1995). Personal satisfaction and the welfare of families, communities, and society. In G. B. Melton (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Vol. 42. The individual, the family, and social good: Personal fulfilment in times of change (pp. ix–xxvii). University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Melton, G. B. (2010). In search of the highest attainable standard of mental health for children. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 89(5), 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, R., Gopikumar, V., Jenkins, J., Saraceno, B., & Sashidharan, S. P. (2022). Social vulnerability and mental health inequalities in the “syndemic”: Call for action. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 894370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migacheva, K. (2015). Searching for puzzle pieces: How (social) psychology can help inform human rights policy. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 21(1), 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T., & MacLeod, T. (2014). Aboriginal social policy: A critical community mental health issue. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 33(1), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A., Ardila, R., Zervoulis, K., Nel, J. A., Light, E., & Chamberl, L. (2020). Cross-cultural perspectives of LGBTQ psychology from five different countries: Current state and recommendations. Psychology & Sexuality, 11(1), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S. M., & Vollhardt, J. R. (2016). ’You can’t give a syringe with unity’: Rwandan responses to the government’s single recategorization policies. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy (ASAP), 16(1), 325–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowat, J. G. (2020). Interrogating the relationship between poverty, attainment and mental health and wellbeing: The importance of social networks and support—A Scottish case study. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(3), 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtarov, F. (2022). Combining behavioural and reflective policy tools for the environment: A scoping review of behavioural public policy literature. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67, 714–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz Neto, J. S., de Lima, A. F., Mir, L. L., & França, L. d. C. (2014). Vigiar e assistir: Reflexões sobre o direito à assistência da ‘adolescência pobre’ = To watch and to attend: Reflections on legal assistance of ‘poor adolescent’. Psicologia em Estudo, 19(2), 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbigging, K., & Ridley, J. (2018). Epistemic struggles: The role of advocacy in promoting epistemic justice and rights in mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 219, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbigging, K., Ridley, J., McKeown, M., Machin, K., & Poursanidou, K. (2015). ‘When you haven’t got much of a voice’: An evaluation of the quality of Independent Mental Health Advocate (IMHA) services in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 23(3), 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D., & Gordon, F. (Eds.). (2021). Leading works in law and social justice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K. S. (2012). Global mental health: A resource primer for exploring the domain. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 1(3), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogolsky, B. G., Monk, J. K., Rice, T. M., & Oswald, R. F. (2019). As the states turned: Implications of the changing legal context of same-sex marriage on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(10), 3219–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OHCHR (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights). (2022). OHCHR and good governance. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/good-governance (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- OPSI (Observatory of Public Sector Innovation). (2021). Behavioural insights units. Available online: https://oecd-opsi.org/bi-units/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Oster, C., Henderson, J., Lawn, S., Reed, R., Dawson, S., Muir-Cochrane, E., & Fuller, J. (2016). Fragmentation in Australian Commonwealth and South Australian State Policy on mental health and older people: A governmentality analysis. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 20(6), 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österman, K., Björkqvist, K., & Wahlbeck, K. (2014). Twenty-eight years after the complete ban on the physical punishment of children in Finland: Trends and psychosocial concomitants. Aggressive Behavior, 40(6), 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucchi, J., Rodrigues, F., Deotti, A., Jardim, L. N., & Calais, L. B. d. (2011). Psicologia e políticas públicas em HIV/AIDS: Algumas reflexões = Psychology and public policy in HIV/AIDS: Some reflections. Psicologia & Sociedade, 23, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, I., Evans-Lacko, S., Semrau, M., Barry, M. M., Chisholm, D., Gronholm, P., Egbe, C. O., & Thornicroft, G. (2016). Promotion, prevention and protection: Interventions at the population- and community-levels for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F. (2011). SPSSI and racial research. Journal of Social Issues, 67(1), 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J. d. C., & Sousa, S. M. G. (2020). Uma Avaliação da Criança como Sujeito Assujeitado no Processo Judicial = An assessment of the child as an objectified subject in the judicial process. Avaliação Psicológica, 19(2), 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premachandra, B., & Lewis, N. A. (2022). Do we report the information that is necessary to give psychology away? A scoping review of the psychological intervention literature 2000–2018. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pykett, J., Jones, R., & Whitehead, M. (2017). Introduction: Psychological governance and public policy. In J. Pykett, R. Jones, & M. Whitehead (Eds.), Psychological governance and public policy: Governing the mind, brain and behaviour (pp. 1–20). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rami, F., Searight, H. R., Dryjanska, L., & Battista, P. (2022). COVID-19—International psychology’s role in addressing healthcare disparities and ethics in marginalized communities. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 11(2), 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., & Horne, S. G. (2010). Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(1), 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K. (2017). Editorial: Psychology and policy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, L. M., Ayón, C., & Gurrola, M. (2013). Estamos traumados: The effect of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, B. D., & Krauss, D. A. (2015). The psychology of law: Human behavior, legal institutions, and law. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Mazas, M. (2015). The construction of ‘official outlaws’ Social-psychological and educational implications of a deterrent asylum policy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, C., & Adlam, J. (2013). Knowing your place and minding your own business: On perverse psychological solutions to the imagined problem of social exclusion. Ethics and Social Welfare, 7(2), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, F., Duffy, L., & Torok, M. (2022). Can government responses to unemployment reduce the impact of unemployment on suicide? A systematic review. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 43(1), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, D. (1995). Power and the origins of unhappiness: Working with individuals. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 5, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, A. P. (2010). The healthy people 2010 outcomes for the care of children with special health care needs: An effective national policy for meeting mental health care needs? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(3), 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z., Momartin, S., Silove, D., Coello, M., Aroche, J., & Tay, K. W. (2011). Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Social Science & Medicine, 72(7), 1149–1156, (Correction in “Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies”, 2015, Social Science & Medicine, 138, 101). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39(3), 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toquero, C. M. D. (2021). Provision of mental health services for people with disabilities in the Philippines amid Coronavirus outbreak. Disability & Society, 36(6), 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S. A., Santiago, C. D., Walts, K. K., & Richards, M. H. (2018). Immigration policy, practices, and procedures: The impact on the mental health of Mexican and Central American youth and families. American Psychologist, 73(7), 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triana, M. d. C., Jayasinghe, M., Pieper, J. R., Delgado, D. M., & Li, M. (2019). Perceived workplace gender discrimination and employee consequences: A meta-analysis and complementary studies considering country context. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2419–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropp, L. (2023, February 1). Applying the full force of research and theory to social policy. The Psychologist. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/applying-full-force-research-and-theory-social-policy (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. (2017). Report of the special rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/reference/themreport/unhrc/2017/en/116935 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Uribe Aramburo, N. I. (2011). Abuso sexual infantil y administración de justicia en Colombia Reflexiones desde la psicología clínica y forense = Child sexual abuse and the application of justice in Colombia Reflections in clinical psychology and forensics. Pensamiento Psicológico, 9(16), 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Valentim, J. P. (2013). Brazilian Social Psychology in the international context: A commentary. Estudos de Psicologia, 18(1), 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deun, H., Van Acker, W., Fobé, E., & Brans, M. (2018, March 26–28). Nudging in public policy and public management: A scoping review of the literature. PSA 68th Annual International Conference, Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vliert, E., Conway, L. G., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2023). Enriching psychology by zooming out to general mindsets and practices in natural habitats. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(5), 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, M. J. T. (2012). Psychology and social justice: Why we do what we do. American Psychologist, 67(5), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatapuram, S., Bell, R., & Marmot, M. (2010). The right to sutures: Social epidemiology, human rights, and social justice. Health and Human Rights, 12(2), 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vodanovich, S. J., & Piotrowski, C. (2011). Recent legislation in personnel psychology: An update for I/O practitioners. Organization Development Journal, 29(2), 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C., Gale, J., Staerklé, C., & Stuart, J. (2018). Immigration and multiculturalism in context: A framework for psychological research. Journal of Social Issues, 74(4), 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, L., & Hodgson, D. (2019). Social justice theory and practice for social work. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D. G., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Cikara, M., Barch, D. M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2023). State-level macro-economic factors moderate the association of low income with brain structure and mental health in U.S. children. Nature Communications, 14(1), 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A. E., Williams, E., Suzukovich, E., Strangeman, K., & Novins, D. (2012). A mental health needs assessment of urban American Indian youth and families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(3), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, D. (2021). Application of the paternalism principle to constitutional rights: Mental health case-law in Ireland. European Journal of Health Law, 28(3), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S., Aber, J. L., & Morris, P. A. (2013). Drawing on psychological theory to understand and improve antipoverty policies: The case of conditional cash transfers. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. F. K., Zhuang, X. Y., Pan, J. Y., & He, X. S. (2014). A critical review of mental health and mental health-related policies in China: More actions required. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(2), 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M. R., Kulick, A., Garvey, J. C., Sinco, B. R., & Hong, J. S. (2018). LGBTQ policies and resources on campus and the experiences and psychological well-being of sexual minority college students: Advancing research on structural inclusion. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(4), 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) & WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Ximenes, V. M., Cidade, E. C., & Nepomuceno, B. B. (2015). Psicología comunitaria y expresiones psicosociales de la pobreza: Contribuciones para la intervención en políticas públicas = Community psychology and psychosocial expressions of poverty: Contributions for public policy intervention. Universitas Psychologica, 14(4), 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegarfard, M., & Bahramabadian, F. (2014). Sexual orientation and human rights in the Ethics Code of the Psychology and Counseling Organization of the Islamic Republic of Iran (PCOIRI). Ethics & Behavior, 24(5), 350–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas, L. H., & Bradlee, M. H. (2014). Exiling children, creating orphans: When immigration policies hurt citizens. Social Work, 59(2), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria: | |

| Publication Year: | From 2010 to present. |

| Language: | The search was conducted in English. Articles not in English were translated. |

| Types of Research: | Psychology publications, including quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and theoretical papers. |

| Types of Documents: | Peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, reviews, and book chapters, published in a psychology journal or a multidisciplinary journal where the first author is working in the field of psychology. |

| Research Focus: | – Publications focused on psychology AND macro-level factors, including structures, systems, institutions, policies, and laws, at the national, regional, intergovernmental, and supranational levels, with a focus on social justice. – Behavioural insights/behavioural governance, with a focus on social justice. |

| Exclusion Criteria: | |

| Publication Year: | Prior to 2010. |

| Types of Research: | – Protocols. – Testing measures. |

| Types of Documents: | – Book reviews. – Pre-prints. – Abstracts. – Bibliographies. – Editorials. – Letters to editors. – A corrigendum that does not revise the actual content of articles. – Award addresses. – Articles not published in a peer-reviewed psychology journal or a multidisciplinary journal where the first author is working in the field of psychology. |

| Research Focus: | – Psychology AND macro-level factors without a focus on social justice. – Behavioural insights/behavioural governance, without a focus on social justice. – Psychiatry publications. |

| Main Search Terms: 1 AND 2 Minor Search Terms: 3 |

|---|

|

|

| Populations | Subpopulations | Number of Articles | Article Number (Article Numbers Correspond with those in Supplementary File S2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children and/or adolescents | 19, 16.1% | 2, 7, 11, 26, 37, 44, 46, 55, 57, 65, 78, 80, 84, 91, 94, 100, 114, 115, 117 | |

| Children | 4 | 26, 78, 80, 94 | |

| Children and adolescents | 4 | 2, 7, 46, 57 | |

| Adolescents | 1 | 114 | |

| Left-behind children from rural primary schools in remote areas of western China | 1 | 11 | |

| Children with special healthcare needs | 1 | 37 | |

| Youth with obesity | 1 | 115 | |

| Children and/or adolescents and their families | 2 | 65, 91 | |

| Families experiencing separation | 1 | 117 | |

| Families with both parental mental health issues and child protection concerns | 1 | 84 | |

| Professional practitioners such as psychologists working with children | 1 | 100 | |

| Legal professionals working with lawsuits involving children | 1 | 44 | |

| Players in the judicial sector involving children | 1 | 55 | |

| Ethnic minorities | 15, 12.71% | 3, 12, 16, 31, 48, 54, 69, 70, 75, 76, 85, 86, 111, 113, 118 | |

| Latino populations | 2 | 16, 76 | |

| Indigenous and Aboriginal (North Americas and Canada) | 2 | 3, 54 | |

| Asian Americans | 1 | 113 | |

| Black and minority ethnic (BME) communities | 1 | 86 | |

| Eastern Asian and North American populations | 1 | 118 | |

| Rwandan ethnic groups | 1 | 48 | |

| Heterogeneous cultural groups in multicultural societies | 1 | 75 | |

| Immigrants and migrants | 4 | 12, 70, 85, 111 | |

| Ethnic minorities more broadly | 2 | 31, 69 | |

| People with mental health problems and/or substance abuse problems and/or mental health service users | 15, 12.71% | 1, 6, 8, 10, 19, 22, 23, 27, 36, 47, 51, 77, 79, 88, 90 | |

| People with mental health problems and/or substance abuse problems and/or treatment service users | 8 | 8, 19, 22, 23, 27,77, 88, 90 | |

| Individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder | 1 | 79 | |

| Mental health service users and people subject to (involuntary) detention | 2 | 1, 10 | |

| Mental health system stakeholders, service users and advocates more broadly | 4 | 6, 36, 47, 51 | |

| People with mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries | 1 | 27 | |

| LGBTQ+ persons | 13, 11.01% | 4, 9, 13, 15, 17, 20, 32, 34, 62, 87, 99, 103, 104 | |

| Individuals in same-sex relationships | 1 | 4 | |

| Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) individuals | 2 | 32, 104 | |

| LGBTQ individuals and communities | 2 | 13, 62 | |

| The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) community | 1 | 87 | |

| LGBTQ+ clients and professional practitioners such as psychologists | 2 | 34, 103 | |

| Sexual minority (LGBQ+) college students | 1 | 20 | |

| Sexual and gender minority individuals living in Tennessee | 1 | 9 | |

| Transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals | 2 | 17, 99 | |

| Parents of trans and gender-diverse (TGD) youth | 1 | 15 | |

| Miscellaneous populations | 27, 22.88% | 5, 14, 18, 21, 24, 28, 33, 40, 41, 43, 45, 58, 61, 63, 64, 66, 68, 69, 71, 73, 89, 96, 97, 106, 107, 108, 116 | |

| Asylum seekers | 1 | 106 | |

| Refugee populations | 3 | 21, 43, 89 | |

| Individuals with physical or intellectual disabilities | 3 | 40, 68, 96 | |

| Employees | 2 | 18, 116 | |

| Employees experiencing gender discrimination | 1 | 24 | |

| People who are unemployed | 1 | 5 | |

| Disenfranchised individuals living with mental health disorder and/or physical disabilities | 1 | 64 | |

| Citizens affected by HIV/AIDS | 1 | 97 | |

| Populations with lived experience of the Movement for Global Mental Health in low- and middle-income countries | 1 | 107 | |

| Globally socioeconomically disadvantaged | 1 | 71 | |

| Residents in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods | 1 | 41 | |

| Marginalised communities | 1 | 61 | |

| Socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals | 2 | 63, 73 | |

| Adolescents in resource-constrained settings | 1 | 45 | |

| School students who are disadvantaged | 1 | 58 | |

| Adults living in a rural and urban community | 1 | 28 | |

| People experiencing relative food insecurity | 1 | 33 | |

| Historically disadvantaged groups | 1 | 108 | |

| Students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds | 1 | 69 | |

| Ageing populations | 1 | 14 | |

| Women who are subject to detention | 1 | 66 | |

| Other | Professional practitioners | 15, 12.71% | 25, 30, 38, 39, 52, 56, 60, 67, 72, 83, 92, 95, 98, 101, 105 |

| Public policies/laws/rights | 14, 11.86% | 29, 35, 42, 49, 50, 59, 74, 81, 82, 93, 102, 109, 110, 112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moonveld, M.; McVeigh, J. Macropsychology: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Psychology Literature on Public Policy and Law. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030350

Moonveld M, McVeigh J. Macropsychology: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Psychology Literature on Public Policy and Law. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030350

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoonveld, Moonika, and Joanne McVeigh. 2025. "Macropsychology: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Psychology Literature on Public Policy and Law" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030350

APA StyleMoonveld, M., & McVeigh, J. (2025). Macropsychology: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Psychology Literature on Public Policy and Law. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030350