Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior: Mediation Through Ego Depletion and Moderation Through Mindfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior

1.2. Ego Depletion as a Mediator

1.3. Mindfulness as a Moderator

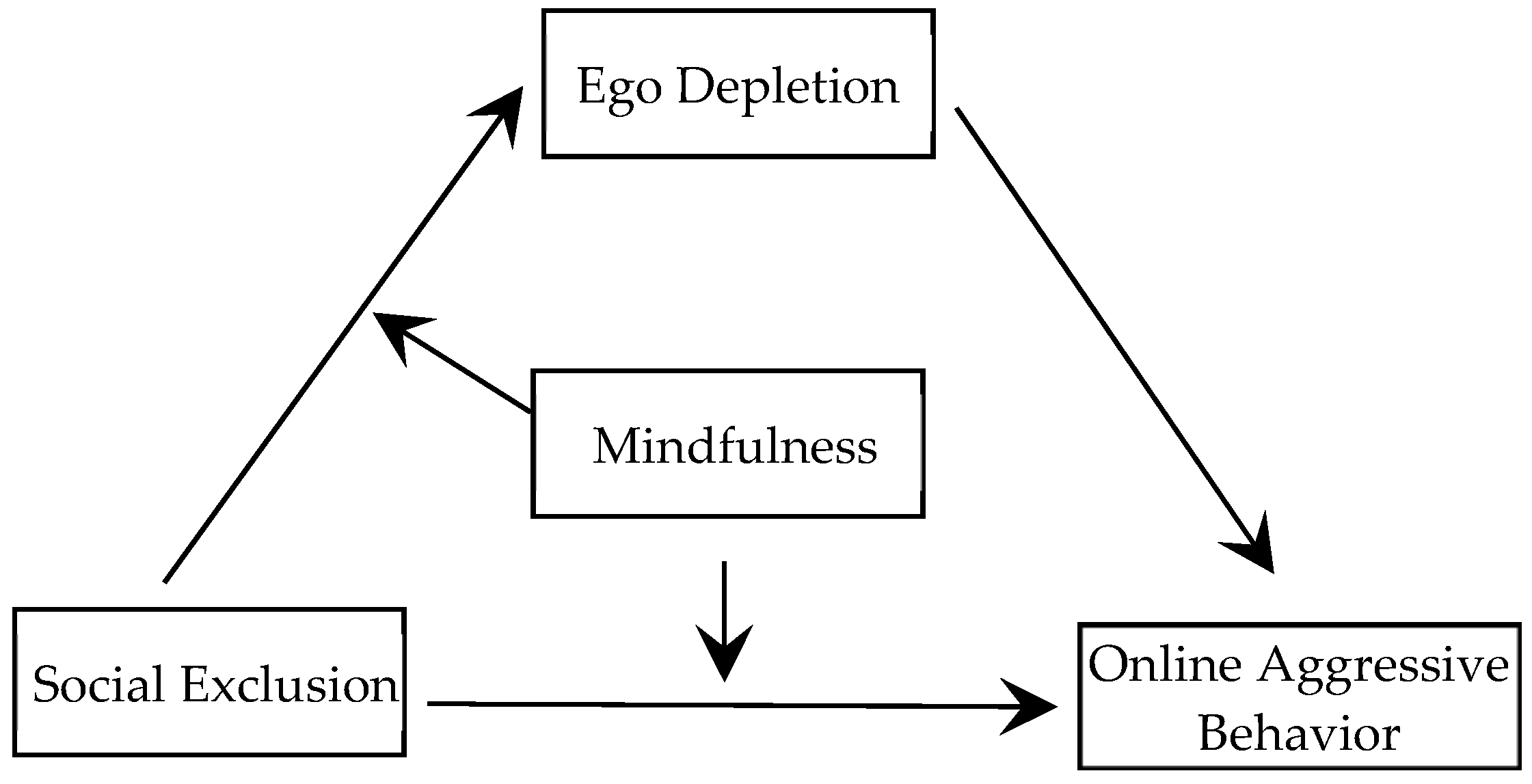

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Mediating Role of Ego Depletion

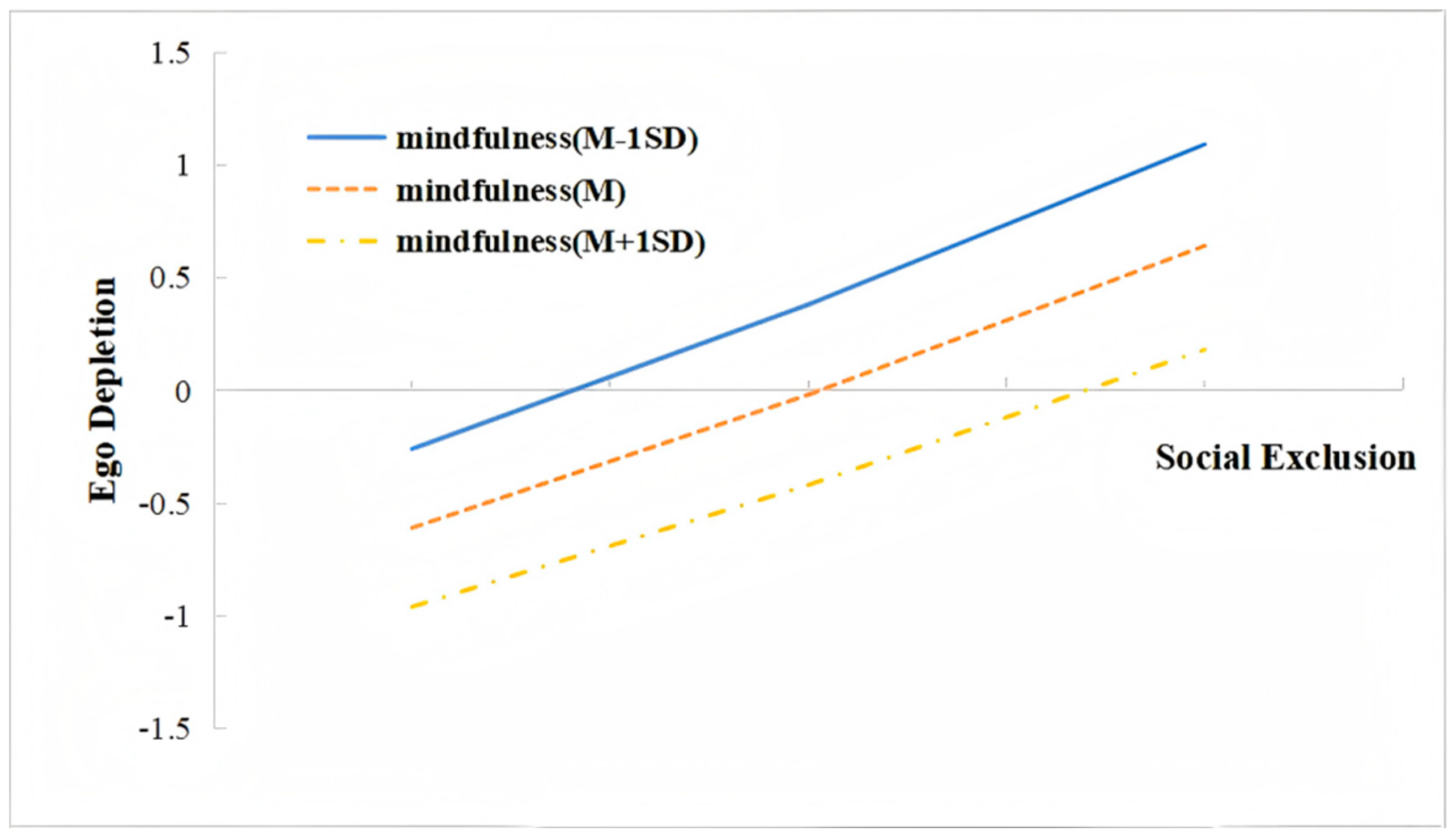

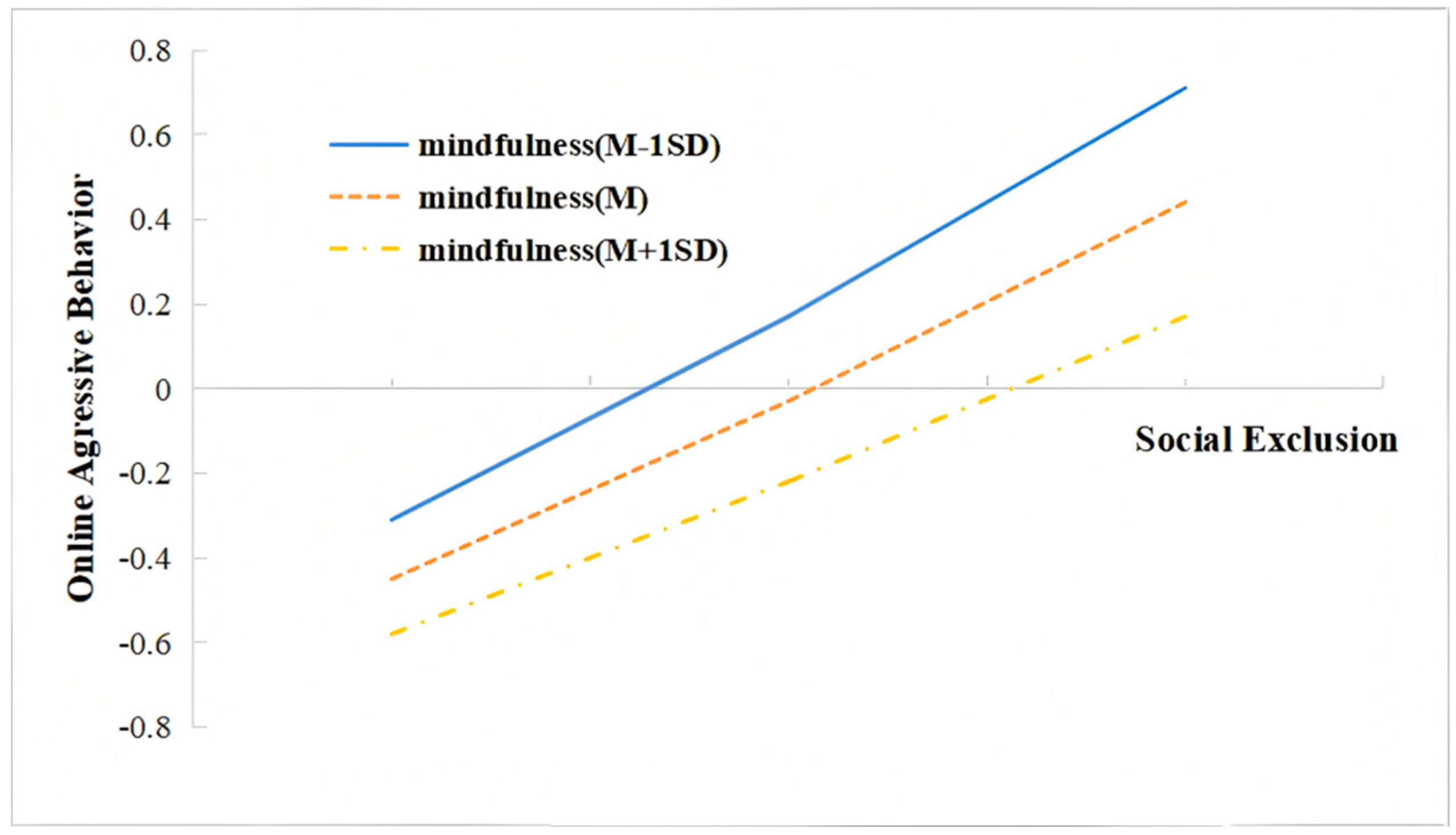

3.3. Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior

4.2. Ego Depletion as a Mediator

4.3. Mindfulness as a Moderator

5. Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J. J., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). The general aggression model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, S., Brunstein Klomek, A., Visoki, E., Moore, T. M., Argabright, S. T., DiDomenico, G. E., Benton, T. D., & Barzilay, R. (2022). Association of cyberbullying experiences and perpetration with suicidality in early adolescence. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), e2218746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G., & Coşkun, M. (2022). Social exclusion, self-forgiveness, mindfulness, and Internet addiction in college students: A moderated mediation approach. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 20(4), 2165–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C., & Coyne, S. M. (2014). A meta-analysis of sex differences in cyber-bullying behavior: The moderating role of age. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C., Oliphant, H., Gregory, W., & Jones, D. (2016). Ego-depletion and aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 42(6), 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., André, N., Southwick, D. A., & Tice, D. M. (2024). Self-control and limited willpower: Current status of ego depletion theory and research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 60, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Boman, J. H., & Mowen, T. J. (2019). Unpacking the role of conflict in peer relationships: Implications for peer deviance and crime. Deviant Behavior, 40(7), 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, V., Dewald-Kaufmann, J., Padberg, F., & Reinhard, M. A. (2023). Aggressive intentions after social exclusion and their association with loneliness. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 273, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Wang, Y. Z., Wang, J. Y., & Luo, F. (2022). The role of mindfulness in alleviating ostracism. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(6), 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Y., Cui, H., Zhou, R. L., & Jia, Y. Y. (2012). Revision of mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Y., Huo, Y. Q., & Liu, J. (2022). Impact of online anonymity on aggression in ostracized grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Personality and Individual Differences, 188, 111448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2024). 54st statistical report on China’s internet development. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0911/MAIN1726017626560DHICKVFSM6.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, C. A., Wiernik, B. M., Berbary, C. M., Crawford, M., Schlauch, R. C., & Easton, C. J. (2021). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between cyber aggression and substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Mead, N. L., & Vohs, K. D. (2011). How leaders self-regulate their task performance: Evidence that power promotes diligence, depletion, and disdain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q., Zhang, Y. X., & Zhou, Z. K. (2020). Relative deprivation and college students’ online flaming: Mediating effect of ego depletion and gender difference. Psychological Development and Education, 36(2), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z. E., Wang, X. H., & Liu, Q. X. (2018). The relationship between college students self-esteem and cyber aggressive behavior: The role of social anxiety and dual self-consciousness. Psychological Development and Education, 34(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, J., & Miller, E. (1939). Frustration and aggression (p. 116). Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. Z., & Xia, B. L. (2008). The psychologicsal view on social exclusion. Advance in Psychological Science, 16(6), 981–986. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, A. D., Thompson, E. L., Mehari, K. R., Sullivan, T. N., & Goncy, E. A. (2020). Assessment of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization, substance use, and delinquent behavior during early adolescence. Assessment, 27(6), 1213–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favini, A., Lunetti, C., Virzì, A. T., Cannito, L., Culcasi, F., Quarto, T., & Palladino, P. (2024). Online and offline aggressive behaviors in adolescence: The role of self-regulatory self-efficacy beliefs. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardella, J. H., Fisher, B. W., & Teurbe-Tolon, A. R. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of cyber-victimization and educational outcomes for adolescents. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E., Gaylord, S., & Park, J. (2009). The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore, 5(1), 37−44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillions, A., Cheang, R., & Duarte, R. (2019). The effect of mindfulness practice on aggression and violence levels in adults: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T., & Kusumi, T. (2013). How can reward contribute to efficient self-control? Reinforcement of task-defined responses diminishes ego-depletion. Motivation and Emotion, 37(4), 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, D. W. (2010). Cyber-aggression: Definition and concept of cyberbullying. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 20(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, S., Palmitesta, P., Bracci, M., Marchigiani, E., Di Pomponio, I., & Parlangeli, O. (2022). How many cyberbullying(s)? A non-unitary perspective for offensive online behaviours. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0268838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, C. L., Mao, J. X., Yang, Q., Yuan, J. J., & Yang, J. M. (2022). Trait acceptance buffers aggressive tendency by the regulation of anger during social exclusion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J. J., Shao, L., Huang, X. X., Zhang, Y. L., & Yu, G. L. (2023). The relationship between social exclusion and aggression: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 55(12), 1979–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T. L., Lu, G. Z., Zhang, L., Wu, Y. T. N., & Jin, X. Z. (2018). The effect of violent exposure on online aggresive behavior of college students: The role of ruminative responses and internet moral. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 50(9), 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T. L., Wu, Y. T. N., Zhang, L., Lei, Z. Y., & Jia, Y. R. (2024). The transition of online aggressive behavior among college students: A latent transition analysis. Journal of Psychological Science, 47(3), 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinson, A. N. (2003). Understanding the psychology of Internet behaviour: Virtual worlds, real lives. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Ellithorpe, M., & Burt, S. A. (2023). Anonymity and its role in digital aggression: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 72, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Antoniadou, N. (2019). Cyber-bullying and cyber-victimization among undergraduate student teachers through the lens of the general aggression model. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, A., Jose, P. E., & Stuart, J. (2019). ‘I did it for the LULZ’: How the dark personality predicts online disinhibition and aggressive online behavior in adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K., Johnson, R. E., & Barnes, C. M. (2014). Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 124(1), 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H. Y., Xiao, N., Zhou, H. L., Jiang, H. B., Teng, H. C., Liu, P., & Tuo, A. X. (2023). Effect of traditional bullying victimization on cyberaggerssion among college students: The chain mediating roles relative deprivation and anger rumination. China Journal of Health Psychology, 31(4), 624–629. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. N., & Sun, B. H. (2022). The influence of leader mindfulness on emotional exhaustion of university teachers: The mediating role of work-to-personal conflict and moderating role of university teacher mindfulness. Journal of Educational Studies, 18(6), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. H., & Lei, L. (2010). Adolescents’ Internet morality and deviant behavior online. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 42(10), 988–997. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y., Xiao, C. J., Che, J. S., Wang, H. X., & Li, A. M. (2020). Ego depletion impedes rational decision making: Mechanisms and boundary conditions. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(11), 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenovic, M., Osmjanski, V., & Stankovic, S. V. (2021). Cyber-aggression, cyberbullying, and cyber-grooming: A survey and research challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M. M., Martos, ’A., Barrag’an, A. B., P’erez-Fuentes, M. C., & G’azquez, J. J. (2022). Anxiety and depression from Cybervictimization in adolescents: A metaanalysis and meta-regression study. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G. F., Zhou, Z. K., Sun, X. J., & Fan, C. Y. (2015). The effects of perceived Internet anonymity and peers’ online deviant behaviors on college students’ online deviant behaviors: The mediating effect of self-control. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 11(11), 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, G. R., & Hart, T. C. (2021). Context matters (but some contexts matter more): Disentangling the influence of traditional bullying victimization on patterns of cyberbullying outcomes. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 4(1), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S., Smith, P. K., & Blumberg, H. H. (2012). Investigating legal aspects of cyberbullying. Psicothema, 24(4), 640–645. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, F. Y., Zhang, S. Y., Zhou, J. Y., Gou, Y., Gui, M. Q., & Wang, L. (2024). The mediating role of hostile attribution bias in social exclusion affecting aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 50, e22169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana-Orts, C., Mérida-López, S., Rey, L., Chamizo-Nieto, M. T., & Extremera, N. (2023). Understanding the role of emotion regulation strategies in cybervictimization and cyberaggression over time: It is basically your fault! Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 17(2), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I. L. S., Pimentel, C. E., Mariano, T. E., & Dias, E. V. A. (2023). Why do we share aggressive online content? Testing a short cycle model. Aggressive Behavior, 49(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L., & Zhang, D. H. (2021). Behavioral Responses to Ostracism: A perspective from the general aggression model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(06), 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D., Nunes, J., Ferreira, T., & da Costa, A. P. (2017). Cyberbullying and suicidal ideation: Relationship with mood states and consumption of psychoactive substances. European Psychiatry, 41, S400–S401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F., Belsky, J., Skalicka, V., & Wichstrom, L. (2015). Social exclusion predicts impaired self-regulation: A 2-Year longitudinal panel study including the transition from preschool to school. Journal of Personality, 83(2), 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. D., Tian, X., & Zhu, W. F. (2024). The long-term effect of ostracism on cyber aggression: Mutually predictive mediators of hostile automatic thoughts and personal relative deprivation. Current Psychology, 43, 25038–25049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifiletti, E., Giannini, M., Vezzali, L., Shamloo, S. E., Faccini, M., & Cocco, V. M. (2021). At the core of cyberaggression: A group-based explanation. Aggressive Behavior, 48(1), 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Q., Yu, P., Sun, H. L., Zhang, Z. W., & Zhu, Y. Q. (2024). The relationship between social exclusion and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) of college students: The mediating effect of rumination. Current Psychology, 43, 24969–24976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. X., Zhong, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). The effect of self-depletion on aggressive behavior: The role of restorative environments. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 19(01), 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A Temporal Need-Threat Model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 275–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2011). Ostracism: Consequences and coping. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(2), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Lo, M., Bullock, L. M., & Gable, R. A. (2011). Cyber bullying: Practices to face digital aggression. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 16(3), 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F., Kamble, S. V., & Soudi, S. P. (2015). Indian adolescents’ cyber aggression involvement and cultural values: The moderation of peer attachment. School Psychology International, 36, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. J., Zhang, S. Y., & Zeng, Y. Q. (2013). Development and validation of the social exclusion questionnaire for undergraduate. China Journal of Health Psychology, 21(12), 1829–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. L. (2022). Exploring the process of harsh parenting on online aggressive behavior: The mediating role of trait anger. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(5), 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J., Fan, C. Y., Wei, H., Yang, X. J., & Lian, S. L. (2023). The effect of mindfulness on cyberbullying: A moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education, 39(05), 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahner, J., dank, M., Zweig, J. M., & Lachman, P. (2015). The co-occurrence of physical and cyber dating violence and bullying among teens. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(7), 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Zhang, C. Y., & Xu, W. (2022). The relationship of dispositional mindfulness to anxiety and aggressiveness among college students: The mediation of resilience and moderation of left-behind experience. Psychological Development and Education, 38(05), 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. L., Wang, F., Deng, M. L., & Shi, W. D. (2024). The effects of illegitimate tasks on employee silence and voice behavior: Moderated mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39(1), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Wang, Y. L., Lu, H. L., & Yang, Y. (2022). The effects of mindfulness-based training intervention on employees’ ego depletion and work engagement: A field experiment based on ESM. Management Review, 34(8), 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, S. S., Wang, J. M., Liu, L. X., & Li, Z. M. (2016). Effects of social exclusion on ego depletion: The compensation effect of self-awareness. International Journal of Psychology, 51, 1072. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Y., Guo, C., Yuan, H., Liu, Y. L., & Chen, Y. Q. (2022). Effect of mindfulness on stress—Based on monitoring and acceptance theory. Journal of Psychological Science, 45(6), 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. L., Zhang, Y., Fu, Y., & Wang, K. (2024). The relationship between campus ostracism, cyber ostracism and adolescent online aggressive behavior: The mediating effect of sense of coherence and anger rumination. China Journal of Health Psychology, 32(1), 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. L., Wei, F., & Du, H. B. (2020). The impact of workplace ostracism on employee proactive behavior: The mediation effects of ego depletion and the moderation effects of identity orientation. Science of Science and Management of S.&.T, 41(4), 113–129. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Exclusion | 0.69 (0.76) | 1 | |||

| Ego Depletion | 2.46 (1.19) | 0.80 ** | 1 | ||

| Mindfulness | 3.97 (1.27) | −0.36 ** | −0.62 ** | 1 | |

| Online Aggressive Behavior | 1.82 (0.73) | 0.79 ** | 0.80 ** | −0.54 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | R2 | F | β | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ego Depletion | Social Exclusion | 0.64 | 418.61 *** | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 40.17 *** |

| (model 1) | Gender | −0.03 | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.66 | ||

| Age | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.003 | |||

| Time Spent Online Per Day | 0.001 | -0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 | |||

| Online Aggressive Behavior (model 2) | Social Exclusion | 0.70 | 440.58 *** | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 13.41 *** |

| Ego Depletion | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 15.90 *** | |||

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 2.29 * | |||

| Age | -0.02 | -0.04 | 0.002 | −1.78 | |||

| Time Spent Online Per Day | 0.001 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | R2 | F | β | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ego Depletion | Social Exclusion | 0.77 | 528.63 *** | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 38.20 *** |

| (model 1) | Mindfulness | −0.40 | −0.43 | −0.36 | −23.18 *** | ||

| Social Exclusion × Mindfulness | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.02 | −3.29 ** | |||

| Gender | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.01 | −1.54 | |||

| Age | 0.003 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.25 | |||

| Time Spent Online Per Day | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.69 | |||

| Online Aggressive Behavior | Social Exclusion | 0.72 | 348.58 *** | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 15.47 *** |

| (Model 2) | Ego Depletion | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 8.20 ** | ||

| Mindfulness | −0.20 | −0.24 | −0.15 | −8.34 *** | |||

| Social Exclusion × Mindfulness | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.03 | −3.82 *** | |||

| Gender | 0.06 | −0.004 | 0.13 | 1.85 | |||

| Age | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.003 | −1.70 | |||

| Time Spent Online Per Day | −0.002 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.29 |

| Level of Mindfulness | Conditional Effect | Effect Value | Bootstrap SE | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | M − 1 SD | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| M | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.53 | |

| M + 1 SD | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.47 | |

| Indirect Effect | M − 1 SD | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.30 |

| M | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.27 | |

| M + 1 SD | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Chen, S.-S.; Wei, H.; Hu, Y. Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior: Mediation Through Ego Depletion and Moderation Through Mindfulness. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030346

Zhao J, Chen S-S, Wei H, Hu Y. Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior: Mediation Through Ego Depletion and Moderation Through Mindfulness. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030346

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jing, Shi-Sheng Chen, Hua Wei, and Yu Hu. 2025. "Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior: Mediation Through Ego Depletion and Moderation Through Mindfulness" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030346

APA StyleZhao, J., Chen, S.-S., Wei, H., & Hu, Y. (2025). Social Exclusion and Online Aggressive Behavior: Mediation Through Ego Depletion and Moderation Through Mindfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030346