How Epistemic Curiosity Influences Digital Literacy: Evidence from International Students in China

Abstract

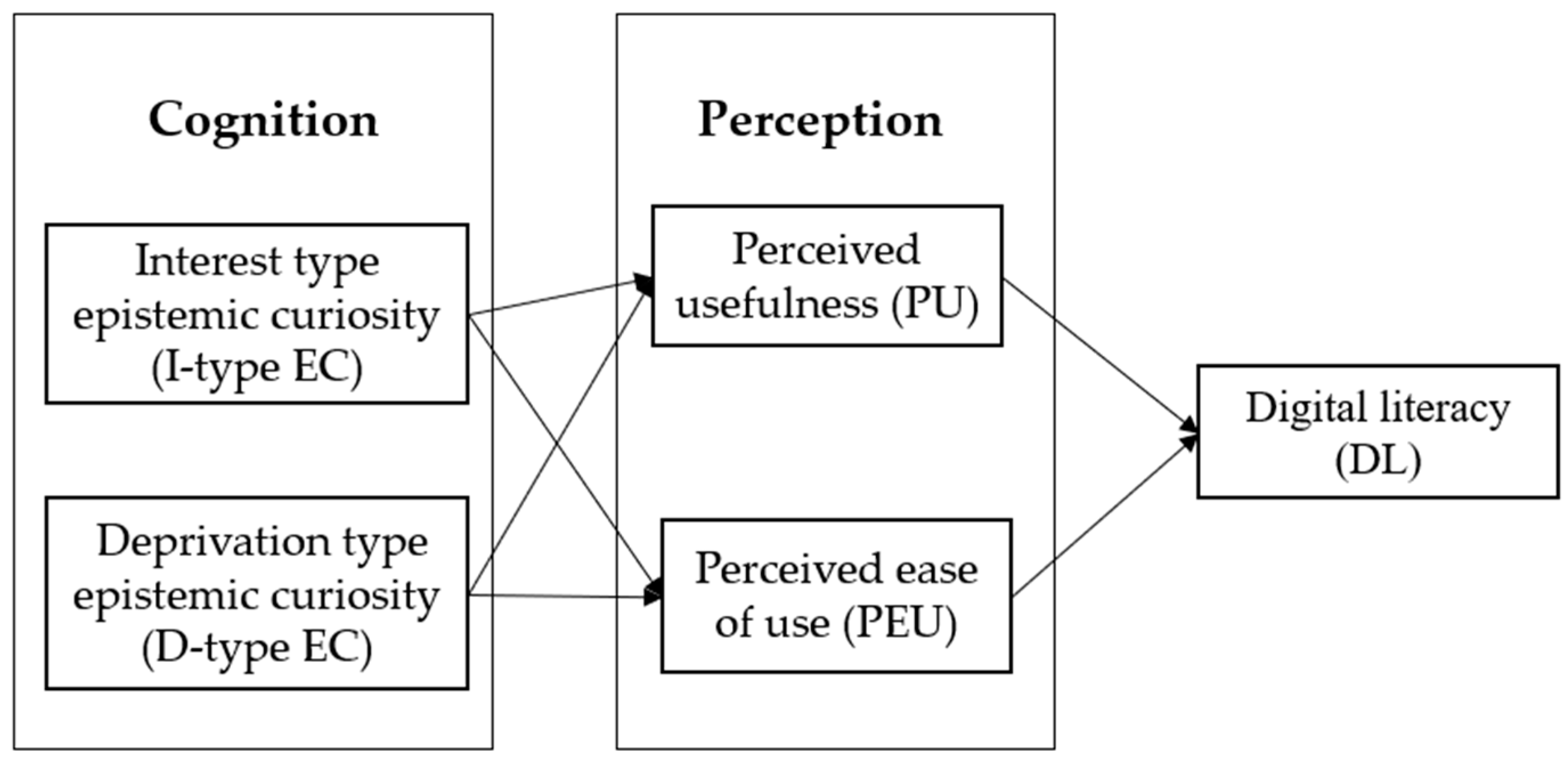

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Influence of Epistemic Curiosity on International Students’ Digital Literacy in China

2.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Usefulness

2.3. The Mediating Role of Perceived Ease of Use

3. Method

3.1. Instrument Development

3.2. Participants and Procedure

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Model Fit

4.2. Direct-Effect Test

4.3. Mediator Effect Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Relevant Questionnaire Items

Appendix A.1. Digital Literacy (Adapted from UNESCO-UIS, 2018)

Appendix A.2. Epistemic Curiosity (Adapted from J. Litman, 2005; J. A. Litman, 2010; J. A. Litman et al., 2010)

Appendix A.3. Perceived Usefulness and Perceiving Ease of Use (Adapted from Davis et al., 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003)

References

- Al-Adwan, A. S., Li, N., Al-Adwan, A., Abbasi, G. A., Albelbisi, N. A., & Habibi, A. (2023). Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) to predict university students’ intentions to use metaverse-based learning platforms. Educational Information Technology, 28(11), 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfadda, H. A., & Mahdi, H. S. (2021). Measuring students’ use of zoom application in language course based on the technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50(4), 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hattami, H. M. (2024). What factors influence the intention to adopt blockchain technology in accounting education? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hattami, H. M. (2025). Understanding how digital accounting education fosters innovation: The moderating roles of technological self-efficacy and digital literacy. The International Journal of Management Education, 23(2), 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hattami, H. M., Al-Adwan, A. S., Abdullah, A. A. H., & Al-Hakimi, M. A. (2023). Determinants of customer loyalty toward mobile wallet services in Post-COVID-19: The moderating role of trust. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2023(1), 9984246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hattami, H. M., & Almaqtari, F. A. (2023). What determines digital accounting systems’ continuance intention? An empirical investigation in SMEs. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B., Wang, J., & Chai, C. S. (2021). Understanding Hong Kong primary school English teachers’ continuance intention to teach with ICT. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(4), 528–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Yao, L., Duan, C., Sun, X., & Niu, G. (2022). Deviant peer affiliation and adolescent tobacco and alcohol use: The roles of tobacco and alcohol information exposure on social networking sites and digital literacy. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, O. I., Aviles, O. F., & Rodriguez-Guerrero, C. (2020). Effects of presence and challenge variations on emotional engagement in immersive virtual environments. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 28(5), 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. H. (2023). An epistemic curiosity-evoking model for immersive virtual reality narrative reading: User experience and the interaction among epistemic curiosity, transportation, and attitudinal learning. Computers & Education, 201, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtestani, R., & Hojatpanah, S. (2020). Digital literacy of EFL students in a junior high school in Iran: Voices of teachers, students, and Ministry Directors. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 635–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2024). Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy. Asia-Pacific Education Research, 33, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L., & Sumettikoon, P. (2024). An empirical analysis of EFL teachers’ digital literacy in Chinese higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K. Y., Reichert, F., Cagasan, L. P., Jr., de La Torre, J., & Law, N. (2020). Measuring digital literacy across three age cohorts: Exploring test dimensionality and performance differences. Computers & Education, 157, 103968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y. J., Lim, K. Y., & Kim, N. H. (2016). The effects of secondary teachers’ technostress on the intention to use technology in South Korea. Computers & Education, 95, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., Stiksma, M. C., Disabato, D. J., McKnight, P. E., Bekier, J., Kaji, J., & Lazarus, R. (2018). The five-dimensional curiosity scale: Capturing the bandwidth of curiosity and identifying four unique subgroups of curious people. Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Youm, H., Kim, S., Choi, H., Kim, D., Shin, S., & Chung, J. (2024). Exploring the influence of youtube on digital health literacy and health exercise intentions: The role of parasocial relationships. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y. B., & Lee, S. H. (2017). Mobile gamer’s epistemic curiosity affecting continuous play intention. Focused on players’ switching costs and epistemic curiosity. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D. M., & Choi, Y. Y. (2010). Knowledge search and people with high epistemic curiosity. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(1), 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriola, M., Litman, J. A., Mussel, P., De Santis, R., Crowson, H. M., & Hoffman, R. R. (2015). Epistemic curiosity and self-regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. W. Y., Hsu, Y. T., & Cheng, K. H. (2022). Do curious students learn more science in an immersive virtual reality environment? Exploring the impact of advance organizers and epistemic curiosity. Computers & Education, 182, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Ma, X., Ma, S., & Gao, F. (2024). Role of green finance in regional heterogeneous green innovation: Evidence from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Yue, C., Ma, S., Ma, X., Gao, F., Zheng, Y., & Li, X. (2023). Life cycle assessment of car energy transformation: Evidence from China. Annals of Operations Research, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Ma, S., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Friends or foes? the effect of iot platform entry into smart device market under quantity discount pricing contract. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 10984–10997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R., Yang, J., Jiang, F., & Li, J. (2023). Does teacher’s data literacy and digital teaching competence influence empowering students in the classroom? Evidence from China. Educational Information Technology, 28(3), 2845–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litman, J. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition and Emotion, 19(6), 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, J. A. (2010). Relationships between measures of I-and D-type curiosity, ambiguity tolerance, and need for closure: An initial test of the wanting-liking model of information-seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(4), 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, J. A., Crowson, H. M., & Kolinski, K. (2010). Validity of the interest-and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity distinction in non-students. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, X., Ma, S., & Li, M. (2024). A chain mediation model of entrepreneurial teachers’ experience and teaching competency: Evidence from China. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(1), 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., Jin, X., Gong, J., & Li, X. (2025). China’s national image in the classroom: Evidence of bicultural identity integration. Current Psychology, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., Li, L., Zuo, J., Gao, F., Ma, X., Shen, X., & Zheng, Y. (2024). Regional integration policies and urban green innovation: Fresh evidence from urban agglomeration expansion. Journal of Environmental Management, 354, 120485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S., Reinders, H., & Darasawang, P. (2022). A classroom-based study on the antecedents of epistemic curiosity in L2 learning. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 51(2), 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nami, F., & Asadnia, F. (2024). Exploring the effect of EFL students’ self-made digital stories on their vocabulary learning. System, 120, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59(3), 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S., & Aavakare, M. (2021). An assessment of the interplay between literacy and digital Technology in Higher Education. Educational Information Technology, 26(4), 3893–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Going digital: Shaping policies, improving lives—Summary. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/going-digital/going-digital-synthesis-summary.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Özparlak, Ç. S. (2022). Digital literacy and views of the COVID-19 pandemic of students who prepared for musical aptitude tests during the pandemic. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 10(1), 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P., Chaudhary, K., Sharma, B., & Hussein, S. (2023). Essaying the design, development, and validation processes of a new digital literacy scale. Online Information Review, 47(2), 371–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N., Khan, S. U., Shaheen, I., Alotaibi, F. A., Alnfiai, M. M., & Arif, M. (2024). Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Computers in Human Behavior, 154, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., Fantin, A. R., Prabhu, N., Guan, C., & Dattakumar, A. (2016). Digital literacy and knowledge societies: A grounded theory investigation of sustainable development. Telecommunications Policy, 40(7), 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A., & Rey, G. D. (2020). COVID-19 as an accelerator for digitalization at a German university: Establishing hybrid campuses in times of crisis. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(3), 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A., Rubio-Rico, L., McClelland, G. T., Monserrate-Gómez, S., Font-Jiménez, I., & de Molina-Fernández, I. (2022). Co-designing and piloting an integrated digital literacy and language toolkit for vulnerable migrant students in higher education. Educational Information Technology, 27(5), 6847–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, H., Saeed, M. A., & Chen, B. (2024). An empirical investigation of acculturative stress among international Muslim students in Tianjin, China. Multicultural Education Review, 1–18. (accessed on 26 February 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2021). The prospective role of epistemic curiosity in national standardized test performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 88, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y. R. (2015). Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explore the effects of a Course Management System (CMS)-Assisted EFL writing instruction. CALICO Journal, 32(1), 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO IITE. (2022). UNESCO IITE releases its new medium-term strategy for 2022–25. Available online: https://iite.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/UNESCO-IITE-Medium-Term-Strategy-2022-2025.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- UNESCO-UIS. (2018). A global framework of reference on digital literacy skills for indicator 4.4.2. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip51-global-framework-reference-digital-literacy-skills-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. (2024). The effect of Chinese EFL students’ digital literacy on their Technostress and Academic Productivity. Asia-Pacific Education Research, 33(4), 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Zheng, Y., Ma, S., & Lu, J. (2023). Does human capital matter for energy consumption in China? Evidence from 30 Chinese provinces. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 93030–93043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Zheng, Y., Ma, S., & Lu, J. (2024). Does higher vocational education matter for rural revitalization? Evidence from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Pan, Z., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2024). The predicting role of EFL students’ achievement emotions and technological self-efficacy in their technology acceptance. Asia-Pacific Education Research, 33(4), 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., & Zhang, C. Y. (2014). Empirical study on continuance intentions towards E-Learning 2.0 systems. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(10), 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | Factors | Chi/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | I-type EC, D-type EC, PU, PEU, DL | 2.158 | 0.057 | 0.046 | 0.911 | 0.912 | 0.904 |

| Four-factor model | I-type EC, D-type EC, PU + PEU, DL | 2.545 | 0.066 | 0.053 | 0.881 | 0.882 | 0.872 |

| Three-factor model | I-type EC + D-type EC, PU + PEU, DL | 2.701 | 0.070 | 0.055 | 0.868 | 0.869 | 0.859 |

| Two-factor model | I-type EC + D-type EC + PU + PEU, DL | 3.146 | 0.078 | 0.059 | 0.833 | 0.834 | 0.823 |

| Single-factor model | I-type EC + D-type EC + PU + PEU + DL | 4.002 | 0.092 | 0.071 | 0.766 | 0.768 | 0.752 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.538 | 0.499 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age | 2.867 | 1.035 | −0.345 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Study stage | 3.314 | 0.776 | −0.233 ** | 0.689 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Major | 1.725 | 0.654 | −0.329 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.059 | 1 | |||||||

| Cumulative residence time in China | 2.116 | 1.042 | −0.104 | 0.154 ** | 0.060 | −0.074 | 1 | ||||||

| Chinese study time | 3.006 | 1.526 | 0.130 * | −0.381 ** | −0.373 ** | 0.044 | 0.221 ** | 1 | |||||

| I-type EC | 3.721 | 0.860 | −0.262 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.109 * | −0.034 | −0.276 ** | 1 | ||||

| D-type EC | 3.567 | 0.739 | −0.207 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.144 ** | −0.016 | −0.216 ** | 0.659 ** | 1 | |||

| PU | 3.930 | 0.746 | −0.113 * | 0.157 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.046 | −0.020 | −0.165 ** | 0.609 ** | 0.591 ** | 1 | ||

| PEU | 3.501 | 0.795 | −0.210 ** | 0.138 ** | 0.223 ** | 0.122 * | −0.022 | −0.222 ** | 0.677 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.614 ** | 1 | |

| DL | 3.811 | 0.634 | −0.158 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.169 ** | 0.010 | −0.151 ** | 0.620 ** | 0.590 ** | 0.720 ** | 0.631 ** | 1 |

| Hypothesis | Coefficients | S.E. | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-type EC→DL | 0.472 | 0.051 | *** | Supported |

| D-type EC→DL | 0.393 | 0.058 | *** | Supported |

| I-type EC→PU | 0.500 | 0.058 | *** | Supported |

| I-type EC→PEU | 0.612 | 0.064 | *** | Supported |

| PU→DL | 0.508 | 0.059 | *** | Supported |

| D-type EC→PU | 0.419 | 0.069 | *** | Supported |

| D-type EC→PEU | 0.442 | 0.074 | *** | Supported |

| PEU→DL | 0.227 | 0.064 | ** | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Coefficients | S.E. | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | p-Value | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| I-type EC→PU→DL | 0.254 | 0.054 | 0.152 | 0.362 | *** | Supported |

| I-type EC→PEU→DL | 0.139 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.256 | ** | Supported |

| D-type EC→PU→DL | 0.213 | 0.050 | 0.119 | 0.315 | *** | Supported |

| D-type EC→PEU→DL | 0.101 | 0.044 | 0.028 | 0.201 | ** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, S.; Jin, X.; Li, X.; Dong, H.; Dong, X.; Tang, B. How Epistemic Curiosity Influences Digital Literacy: Evidence from International Students in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030286

Ma S, Jin X, Li X, Dong H, Dong X, Tang B. How Epistemic Curiosity Influences Digital Literacy: Evidence from International Students in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030286

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Shaojun, Xuan Jin, Xin Li, Hongming Dong, Xuehang Dong, and Bowen Tang. 2025. "How Epistemic Curiosity Influences Digital Literacy: Evidence from International Students in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030286

APA StyleMa, S., Jin, X., Li, X., Dong, H., Dong, X., & Tang, B. (2025). How Epistemic Curiosity Influences Digital Literacy: Evidence from International Students in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030286