Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): A Narrative Study of the Social and Clinical Impact of CHD Diagnosis on Their Role and Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Methodological Assumptions

- Generative Repertories (GR): they allow to produce a shift towards narratives that are different from those that have already become available;

- Stabilization Repertories (SR): they do not allow to produce a shift towards ‘other’ narratives from those that are already available, allowing them to keep the current one stable instead;

- Hybrid Repertories (HR): they can have both a generative and maintenance value, as they draw their value based on the class of the Repertories that they interact with in the narrative.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Scientific Data Validation

3. Results

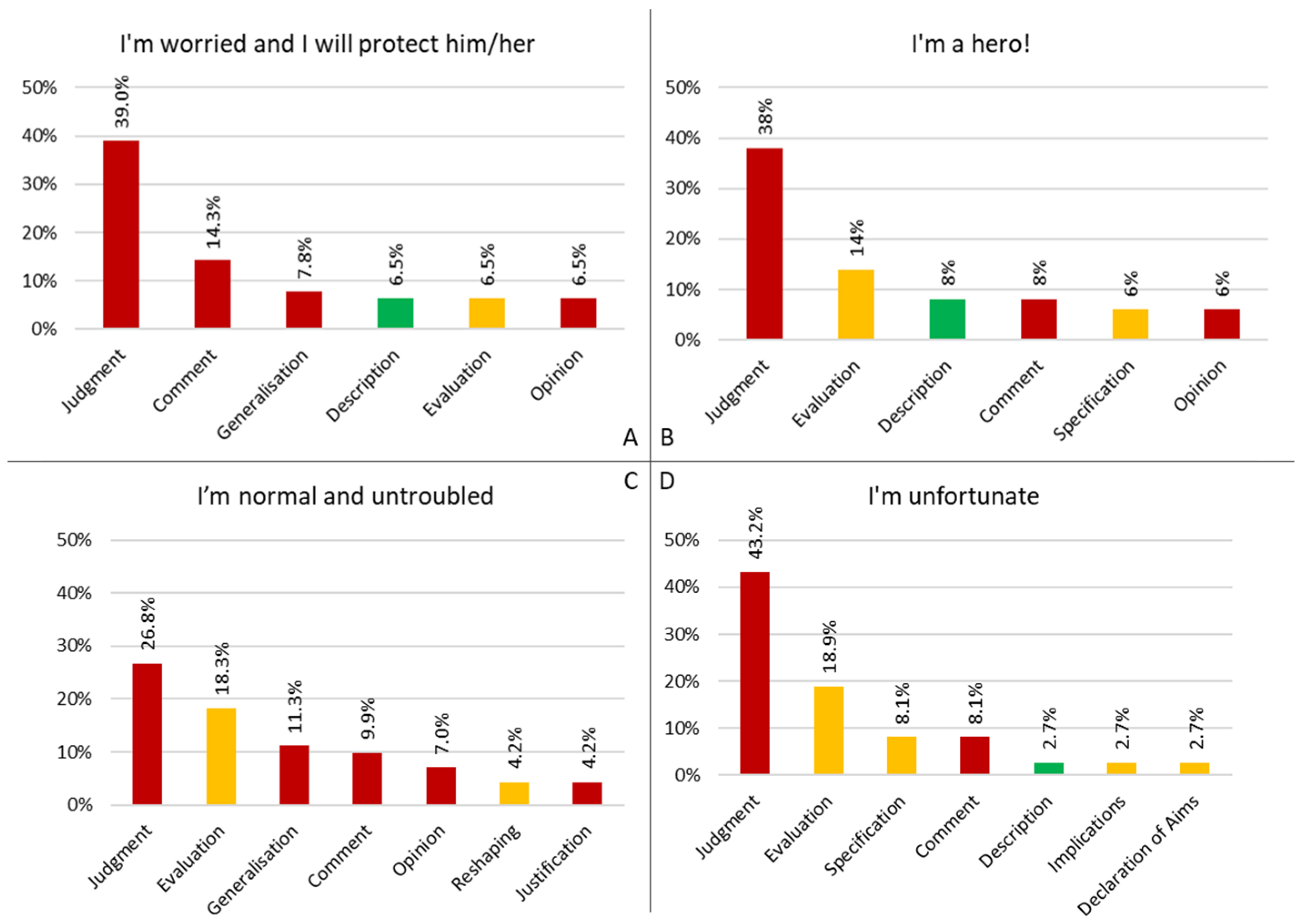

3.1. How Parents Configure Their Role

3.1.1. I’m Worried and I Will Protect Him/Her

3.1.2. I’m a Hero!

3.1.3. I’m Normal and Untroubled

3.1.4. I’m Unfortunate

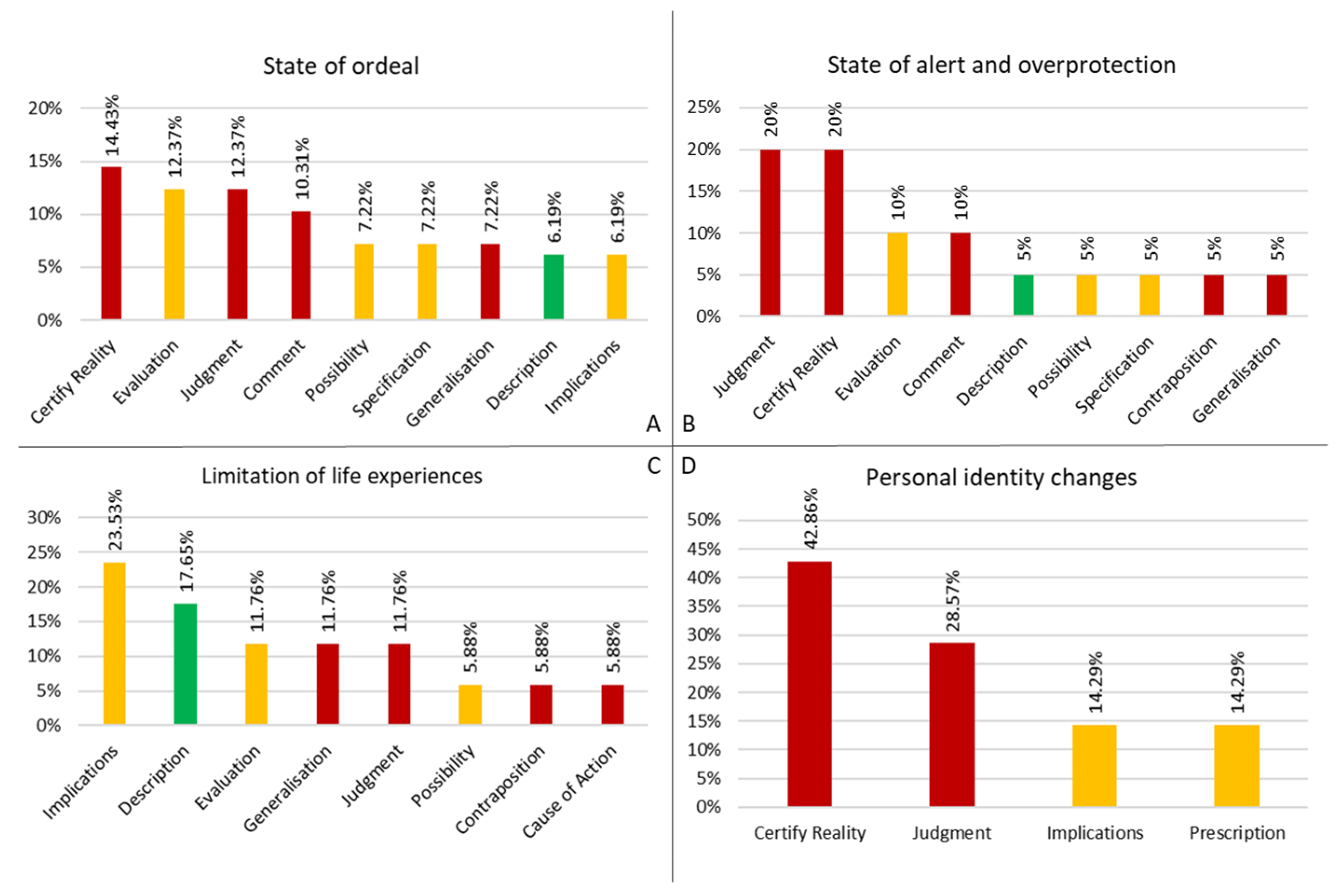

3.2. The Clinical and Social Repercussions

3.2.1. State of Ordeal

3.2.2. State of Alert and Overprotection

3.2.3. Limitation of Life Experiences

3.2.4. Personal Identity Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Discursive Repertory | Description |

|---|---|

| Certify Reality—CR (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by stating a clear, certain, and unalterable state of thing. The possibility of transformation is unforeseen for this reality. |

| Description—DS (GR) | Discursive modality that configures reality as a common heritage that does not belong exclusively to any narrator and it needs everyone’s contribution to be maintained. It configures a current or past reality as if the narrator were responding to a question starting with ‘how’ instead of ‘why’ |

| Specification—SI (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by providing a generation or maintenance of an explicit and detailed description regarding the configuration it is associated with, limiting its range of application to what is expressed. |

| Possibility—PS (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by using one’s own and exclusive criteria as the only argumentative foundation, without making them explicit and describing them in order make them shared. It configures reality in probabilistic, possibilistic, and uncertain terms. |

| Opinion—OI (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by making explicit that the contents are valid and delimited within narrator’s own and exclusive perspective. |

| Targeting—TG (GR) | Discursive modality that configures reality in order to set an objective/purpose/goal to another part of the text, defining actions, strategies, interventions, etc. Enables the triggering of a discursive configuration aimed at the pursue of the defined objective/purpose/goal and, in this way, generating modalities belonging to the generative class and of maximum generative impact. |

| Cause of Action—CA (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality through empirical factual connections of cause-effects with value of truth, which determine an immutable course of events. The argumentation is not epistemologically founded. |

| Confirmation—CP (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by validating and supporting what is expressed through the Repertory to which it relates. |

| Contraposition—CT (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality through parallelism between two or more discourse parts, which are connected in terms that one excludes the other. The criteria that allow exclusion are not made explicit. |

| Implications—IP (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality shaping the narrator’s own and exclusive position regarding probable situations that could occur and that have not yet occurred, through a cause–effect rhetorical argumentative link. Those situations are reported in a tense (and time) following the one related to the main action (present perfect-simple past or present or future, present-future, etc.). |

| Judgment—JM (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality according to CR’s processual properties by using moral and/or qualitative attributes without making explicit the criteria used, shaping the narrator’s own and exclusive reality, which is, therefore, not shareable. |

| Prevision—PV (SR) | Discursive modality that configures realities defining/stating a future scenario as a certain result of the development of a current scenario through a cause–effect rhetorical argumentative link. |

| Justification—JT (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by entailing maintenance of the ;current state of things’; it associates a situation to a previous one in order to legitimize a ‘state of things’, obstructing the use of other ways to handle or change what is happening. |

| Non Answer—NA (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality in order to avoid the asked question—according to CR’s processual properties—establishing a ‘state of things’ in which the narrator does not adhere properly to the process introduced by the question itself. |

| Comment—CM (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality in an inappropriate and irrelevant way to what is asked in the question following the narrator’s own and exclusive criteria, which are neither made explicit nor sharable. The argumentation does not allow to answer to the question asked and it uses CR’s processual properties. |

| Generalization—GE (SR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by responding inadequately to the question asked and using cross-context argumentations, thus, not covering what is required. The criteria used are not epistemologically founded. |

| Evaluation—EU (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by stating a ‘state of things’ funded on the narrator’s own and exclusive criteria, which, although explicit, are non-sharable. |

| Declaration of Aims—DA (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by transposing the object of the request in a future perspective, without elements of certainty and probability as foundation. |

| Proposal—PP (GR) | Discursive modality that configures uncertain reality, possible in an achievable way and aimed at handling what is requested/offered according to TG’s processual properties. |

| Deresponsibility—DE (SR) | Discursive mode that configures reality by delegating to third parties processes that are proper and exclusive to the narrator. |

| Prescription—PT (HR) | Discursive modality that configures reality as orders/directions given by a third ‘point of view’ position compared to the narrator’s one. Establishes rules and/or objectives and/or roles to follow, in terms of what one ‘has to do’ or ‘has not to do’. The argumentation acquires a structure founded on a relation of necessity set by a part of the text. |

| Reshaping—RS (HR) | Discursive modality that configures realities that limit the generative potential of what the configuration offers. The argumentation’s reference is third and not referable to the narrator. |

| Consideration—CS (GR) | Discursive modality that configures reality by proposing an argumentation which uses criteria of analysis that can be shared among several interlocutors, namely that do not belong to any narrators exclusively, but need all of their contribution to maintain them (the criteria). |

| Anticipation—AT (GR) | Discursive modality that configures reality through an argumentation shaped according to CS’s processual properties. This Repertory configures many different and uncertain situation that can occur and that have not yet occurred using PS’s processual properties. |

References

- Alkan, F., Sertcelik, T., Yalın Sapmaz, S., Eser, E., & Coskun, S. (2017). Responses of mothers of children with CHD: Quality of life, anxiety and depression, parental attitudes, family functionality. Cardiology in the Young, 27(9), 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, D., Moro, C., Orrù, L., & Turchi, G. P. (2024). Pupils’ inclusion as a process of narrative interactions: Tackling ADHD typification through MADIT methodology. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellinger, D. C., & Newburger, J. W. (2010). Neuropsychological, psychosocial, and quality-of-life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology, 29(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, E. L., Burström, Å., Hanseus, K., Rydberg, A., Berghammer, M., & On behalf on the STEPSTONES-CHD Consortium. (2018). Do not forget the parents-Parents’ concerns during transition to adult care for adolescents with congenital heart disease. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(2), 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, E., Lilja, C., & Sundin, K. (2013). Mothers’ lived experiences of support when living with young children with congenital heart defects. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 19(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burström, Å., Öjmyr-Joelsson, M., Bratt, E.-L., Lundell, B., & Nisell, M. (2016). Adolescents with congenital heart disease and their parents: Needs before transfer to adult care. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 31(5), 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. (2003). Grounded theory. In Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 81–110). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Daliento, L., Mapelli, D., & Volpe, B. (2006). Measurement of cognitive outcome and quality of life in congenital heart disease. Heart, 92(4), 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellafiore, F., Domanico, R., Flocco, S. F., Pittella, F., Conte, G., Magon, A., Chessa, M., Caruso, R., Dellafiore, F., Domanico, R., Flocco, S. F., Pittella, F., Conte, G., Magon, A., Chessa, M., & Caruso, R. (2017). The life experience of parents of Congenital Heart Disease adolescents: A meta-synthesis. Archives of Nursing Practice and Care, 3(2), 031–037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. (2008). Symbolic interactionism and cultural Studies: The politics of interpretation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dijk, T. A. v. (2009). Society and discourse: How social contexts influence text and talk. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elissa, K., Bratt, E.-L., Axelsson, Å. B., Khatib, S., & Sparud-Lundin, C. (2017). Societal norms and conditions and their influence on daily life in children with type 1 diabetes in the west bank in palestine. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 33, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2018). Designing qualitative research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Franich-Ray, C., Bright, M. A., Anderson, V., Northam, E., Cochrane, A., Menahem, S., & Jordan, B. (2013). Trauma reactions in mothers and fathers after their infant’s cardiac surgery. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(5), 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M. K., Karpyn, A., Christofferson, J., McWhorter, L. G., C Demianczyk, A., L Brosig, C., A Jackson, E., Lihn, S., C Zyblewski, S., E Kazak, A., & Sood, E. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to discussing parent mental health within child health care: Perspectives of parents raising a child with congenital heart disease. Journal of Child Health Care, 27(3), 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantt, L. (2002). As normal a life as possible: Mothers and their daughters with congenital heart disease. Health Care for Women International, 23(5), 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfenshtein, N., Hanlon, A. L., Deatrick, J. A., & Medoff-Cooper, B. (2017). parenting stress in parents of infants with congenital heart disease and parents of healthy infants: The first year of life. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 40(4), 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harré, R., & Gillett, G. (1994). The discursive mind. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, K. A., Kovalesky, A., Woods, R. K., & Loan, L. A. (2013). Experiences of mothers of infants with congenital heart disease before, during, and after complex cardiac surgery. Heart & Lung, 42(6), 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearps, S. J., McCarthy, M. C., Muscara, F., Hearps, S. J. C., Burke, K., Jones, B., & Anderson, V. A. (2014). Psychosocial risk in families of infants undergoing surgery for a serious congenital heart disease. Cardiology in the Young, 24(4), 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfricht, S., Latal, B., Fischer, J. E., Tomaske, M., & Landolt, M. A. (2008). Surgery-related posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: A prospective cohort study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 9(2), 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iudici, A., Favaretto, G., & Turchi, G. P. (2019). Community perspective: How volunteers, professionals, families and the general population construct disability: Social, clinical and health implications. Disability and Health Journal, 12(2), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iudici, A., Filosa, E., Turchi, G., & Faccio, E. (2022). Management of the disease of primary immunodeficiencies: An exploratory investigation of the discourses and clinical and social implications. Current Psychology, 41(9), 5925–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iudici, A., & Gagliardo Corsi, A. (2017). Evaluation in the field of social services for minors: Measuring the efficacy of interventions in the Italian service for health protection and promotion. Evaluation and Program Planning, 61, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iudici, A., & Renzi, C. (2015). The configuration of job placement for people with disabilities in the current economic contingencies in Italy: Social and clinical implications for health. Disability and Health Journal, 8(4), 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetam, A.-A. (2014). Experiences and coping strategies of Jordanian parents of children with Beta Thalassaemia Major. University of Hull. [Google Scholar]

- Lawoko, S. (2007). Factors influencing satisfaction and well-being among parents of congenital heart disease children: Development of a conceptual model based on the literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 21(1), 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawoko, S., & Soares, J. J. F. (2002). Distress and hopelessness among parents of children with congenital heart disease, parents of children with other diseases, and parents of healthy children. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(4), 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawoko, S., & Soares, J. J. F. (2006). Psychosocial morbidity among parents of children with congenital heart disease: A prospective longitudinal study. Heart & Lung, 35(5), 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Ahn, J.-A. (2020). Experiences of mothers facing the prognosis of their children with complex congenital heart disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissauer, T., Clayden, G., & Craft, A. (2012). Illustrated textbook of paediatrics (4th ed.). Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- López, R., Frangini, P., Ramírez, M., Valenzuela, P. M., Terrazas, C., Pérez, C. A., Borchert, E., & Trachsel, M. (2016). Well-being and agency in parents of children with congenital heart disease: A survey in Chile. World Journal for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery, 7(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marelli, A. J., Ionescu-Ittu, R., Mackie, A. S., Guo, L., Dendukuri, N., & Kaouache, M. (2014). Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation, 130(9), 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKechnie, A. C., Pridham, K., & Tluczek, A. (2016). Walking the “emotional tightrope” from pregnancy to parenthood: Understanding parental motivation to manage health care and distress after a fetal diagnosis of complex congenital heart disease. Journal of Family Nursing, 22(1), 74–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G. H. (2015). Mind, self, and society: The definitive edition (C. W. Morris, Ed.; D. R. Huebner, & H. Joas, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, F., Fusco, C., & Kirsh, J. A. (2011). «What I Wish You Knew»: Social barriers toward physical activity in youth with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufti, G.-E.-R., Towell, T., & Cartwright, T. (2015). Pakistani children’s experiences of growing up with beta-thalassemia major. Qualitative Health Research, 25(3), 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, P., Grigg, L., & Zentner, D. (2017). Mortality in adults with congenital heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology, 245, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, T., Markwald, R. R., Baldwin, H. S., Keller, B. B., Srivastava, D., & Yamagishi, H. (Eds.). (2016). Etiology and morphogenesis of congenital heart disease: From gene function and cellular interaction to morphology. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nayeri, N. D., Roddehghan, Z., Mahmoodi, F., & Mahmoodi, P. (2021). Being parent of a child with congenital heart disease, what does it mean? A qualitative research. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHLBI. (2022). Congenital heart defects—What are congenital heart defects?

- Oster, M. E., Lee, K. A., Honein, M. A., Riehle-Colarusso, T., Shin, M., & Correa, A. (2013). Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics, 131(5), e1502–e1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E., Fabbian, A., Alfieri, R., Da Roit, A., Marano, S., Mattara, G., Pilati, P., Castoro, C., Cavarzan, M., Dalla Riva, M. S., Orrù, L., & Turchi, G. P. (2022). Critical competences for the management of post-operative course in patients with digestive tract cancer: The contribution of MADIT methodology for a nine-month longitudinal study. Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, J., Dean, S., & Menahem, S. (2013). Infant cardiac surgery: Mothers tell their story: A therapeutic experience. World Journal for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery, 4(3), 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2005). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L. T., & Herman-Kinney, N. J. (2003). Handbook of symbolic interactionism. Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Rychik, J., Donaghue, D. D., Levy, S., Fajardo, C., Combs, J., Zhang, X., Szwast, A., & Diamond, G. S. (2013). Maternal psychological stress after prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. The Journal of Pediatrics, 162(2), 302–307.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabzevari, S., Nematollahi, M., Mirzaei, T., & Ravari, A. (2016). The burden of care: Mothers’ experiences of children with congenital heart disease. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 4(4), 374–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salvini, A. (1998). Argomenti di psicologia clinica. UPSEL Domeneghini. [Google Scholar]

- Salvini, A. (2004). Psicologia clinica. Seconda edizione. UPSEL Domeneghini. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, G. S., Singh, M. K., Pandey, T. R., Kalakheti, B. K., & Bhandari, G. P. (2008). Incidence of congenital heart disease in tertiary care hospital. Kathmandu University Medical Journal (KUMJ), 6(1), 33–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simeone, S., Platone, N., Perrone, M., Marras, V., Pucciarelli, G., Benedetti, M., Dell’Angelo, G., Rea, T., Guillari, A., Da Valle, P., Gargiulo, G., Botti, S., Artioli, G., Comentale, G., Ferrigno, S., Palma, G., & Baratta, S. (2018). The lived experience of parents whose children discharged to home after cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 89(Suppl. 4), 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skreden, M., Skari, H., Malt, U. F., Haugen, G., Pripp, A. H., Faugli, A., & Emblem, R. (2010). Long-term parental psychological distress among parents of children with a malformation—A prospective longitudinal study. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 152A(9), 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D. (2016). Reprogramming approaches to cardiovascular disease: From developmental biology to regenerative medicine. In Etiology and morphogenesis of congenital heart disease. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Wageningen University and Research Library catalog. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tak, Y. R., & McCubbin, M. (2002). Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(2), 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, G. P., Dalla Riva, M. S., Ciloni, C., Moro, C., & Orrù, L. (2021a). The interactive management of the SARS-CoV-2 virus: The social cohesion index, a methodological-operational proposal. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 559842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, G. P., Dalla Riva, M. S., Orrù, L., & Pinto, E. (2021b). How to intervene in the health management of the oncological patient and of their caregiver? A narrative review in the psycho-oncology field. Behavioral Sciences, 11(7), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, G. P., Fabbian, A., Alfieri, R., Da Roit, A., Marano, S., Mattara, G., Pilati, P., Castoro, C., Bassi, D., Dalla Riva, M. S., Orrù, L., & Pinto, E. (2022a). Managing the consequences of oncological major surgery: A short- and medium-term skills assessment proposal for patient and caregiver through M.A.D.I.T. methodology. Behavioral Sciences, 12(3), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., Iudici, A., & Faccio, E. (2019). From suicide due to an economic-financial crisis to the management of entrepreneurial health: Elements of a biographical change management service and clinical implications. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., Orrù, L., Iudici, A., & Pinto, E. (2022b). A contribution towards health. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 28(5), 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., Salvalaggio, I., Croce, C., Dalla Riva, M. S., Orrù, L., & Iudici, A. (2022c). The health of healthcare professionals in Italian oncology: An analysis of narrations through the M.A.D.I.T. methodology. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainberg, D. L., Vardi, A., & Jacoby, R. (2019). The experiences of parents of children undergoing surgery for congenital heart defects: A holistic model of care. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., Roscigno, C. I., Hanson, C. C., & Swanson, K. M. (2015). Families of children with congenital heart disease: A literature review. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 44(6), 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf-King, S. E., Anger, A., Arnold, E. A., Weiss, S. J., & Teitel, D. (2017). Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: A systematic review. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(2), e004862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, A., Celebioglu, A., & Olgun, H. (2009). Distress levels in Turkish parents of children with congenital heart disease. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhou, H., Bai, Y., Chen, Z., Wang, Y., Hu, Q., Yang, M., Wei, W., Ding, L., & Ma, F. (2023). Families under pressure: A qualitative study of stressors in families of children with congenital heart disease. Stress and Health, 39(5), 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Research Aims | Questions | Example of Answer | DR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Describing the role of ‘parent of a child with CHD’ | How would you describe yourself as a parent of a child with congenital heart disease? | I think I learned so much from suffering and fear. But I definitely would have preferred to remain more ignorant, more superficial but more carefree. | Contraposition (SR) |

| How might people who have not experienced congenital heart disease describe a parent of a child with such a condition? | We are usually told that we are strong, but I think others cannot totally understand our fears and emotions. | Judgment (SR) Specification (HR) | |

| Describing the impact of CHD’s psychosocial repercussions on parents’ lives | As a parent of a child with congenital heart disease, how would you describe the repercussions your child’s heart condition has had on you? | I think there is more concern about what happens to him, in the sense that even every little illness or injury leads to “other” reflections and what might happen to him in his condition. | Evaluation (HR) |

| How might people who have not experienced congenital heart disease describe the repercussions of the child’s heart condition on his/her parents? | Apprehension, fear, anxiety. | Certify Reality (SR) |

| Role Configurations |

|---|

| I’m worried and I will protect him/her |

| I’m a hero! |

| I’m normal and untroubled |

| I’m unfortunate |

| Repercussions’ Clusters |

|---|

| State of ordeal |

| State of alert and overprotection |

| Limitation of life experiences |

| Personal identity changes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moro, C.; Iudici, A.; Turchi, G.P. Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): A Narrative Study of the Social and Clinical Impact of CHD Diagnosis on Their Role and Health. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030269

Moro C, Iudici A, Turchi GP. Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): A Narrative Study of the Social and Clinical Impact of CHD Diagnosis on Their Role and Health. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030269

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoro, Christian, Antonio Iudici, and Gian Piero Turchi. 2025. "Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): A Narrative Study of the Social and Clinical Impact of CHD Diagnosis on Their Role and Health" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030269

APA StyleMoro, C., Iudici, A., & Turchi, G. P. (2025). Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): A Narrative Study of the Social and Clinical Impact of CHD Diagnosis on Their Role and Health. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030269