The Trickle-Down Effects of Supervisor Regulatory Foci on Newcomer Task Performance

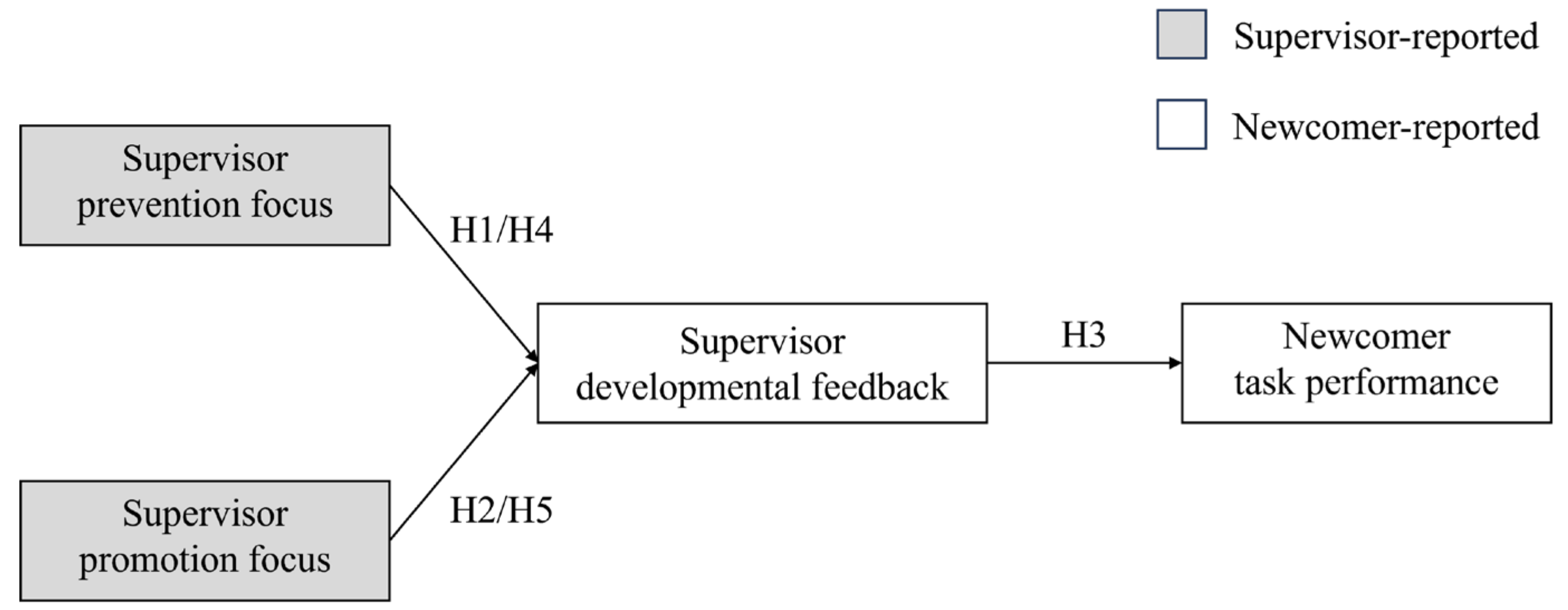

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Regulatory Focus Theory and Leadership

1.2. Supervisor Prevention Focus and Supervisor Developmental Feedback

1.3. Supervisor Promotion Focus and Supervisor Developmental Feedback

1.4. Supervisor Developmental Feedback and Newcomer Task Performance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Supervisor Prevention Focus

2.2.2. Supervisor Promotion Focus

2.2.3. Supervisor Developmental Feedback

2.2.4. Newcomer Task Performance

2.2.5. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Biases

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Hypothetical Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaker, J. L., & Lee, A. Y. (2001). “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S., Khanagha, S., Berchicci, L., & Jansen, J. J. P. (2017). Are managers motivated to explore in the face of a new technological change? The role of regulatory focus, fit, and complexity of decision-making. Journal of Management Studies, 54(2), 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J. B., Carter, M. Z., & Cole, M. S. (2022). The (in)congruence effect of leaders’ narcissism identity and reputation on performance: A socioanalytic multistakeholder perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(10), 1725–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesario, J., Higgins, E. T., & Scholer, A. A. (2008). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Basic principles and remaining questions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A. M., Bauer, T. N., Mansfield, L. R., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Simon, L. S. (2015). Navigating uncharted waters: Newcomer socialization through the lens of stress theory. Journal of Management, 41(1), 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenkopf, E., Guo, J., & Argote, L. (2020). Personnel mobility and organizational performance: The effects of specialist vs. generalist experience and organizational work structure. Organization Science, 31(6), 1601–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z. Z., Zhao, J. J., & Ding, L. (2020). The “wisdom” of golden mean thinking: Research on the mechanism between supervisor developmental feedback and employee creativity. Nankai Business Review, 23(1), 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hamstra, M. R. W., Bolderdijk, J. W., & Veldstra, J. L. (2011). Everyday risk taking as a function of regulatory focus. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(1), 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y., & Sasaki, H. (2022). Effect of leaders’ regulatory-fit messages on followers’ motivation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(7), 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X., Zheng, Y., & Wei, Y. (2024). The double-edged sword effect of illegitimate tasks on employee creativity: Positive and negative coping perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N., & Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T., & Pinelli, F. (2022). Regulatory focus and fit effects in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. J., Zhang, S., Lount, R. B., & Tepper, B. J. (2024). When leaders heed the lessons of mistakes: Linking leaders’ recall of learning from mistakes to expressed humility. Personnel Psychology, 77(2), 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O., Vriend, T., Said, R., & Nijstad, B. (2024). Leader regulatory goal setting and employee creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. D., Smith, M. B., Wallace, J. C., Hill, A. D., & Baron, R. A. (2015). A review of multilevel regulatory focus in organizations. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1501–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. E., King, D. D., Lin, S., Scott, B. A., Jackson Walker, E. M., & Wang, M. (2017). Regulatory focus trickle-down: How leader regulatory focus shapes follower regulatory focus and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 140, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R., & Van Dijk, D. (2007). Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R., & Van Dijk, D. (2019). Keep your head in the clouds and your feet on the ground: A multifocal review of leadership-followership self-regulatory focus. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 509–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, O. P., Ehrnrooth, M., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., Sumelius, J., & Vuorenmaa, H. (2022). Serving to help and helping to serve: Using servant leadership to influence beyond supervisory relationships. Journal of Management, 48(3), 764–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J., Lanaj, K., Bono, J., & Campana, K. (2016). Daily shifts in regulatory focus: The influence of work events and implications for employee well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(8), 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K., Chang, C. D., & Johnson, R. E. (2012). Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 998–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Y., Zhou, X. H., & Jiang, S. Y. (2022). The influencing mechanism of supervisor developmental feedback on newcomers’ work meaningfulness. East China Economic Management, 36(7), 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N., Harris, T. B., Boswell, W. R., & Xie, Z. (2011). The role of organizational insiders’ developmental feedback and proactive personality on newcomers’ performance: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S., Watts, D., Feng, J., Wu, Y., & Yin, J. (2024). Unpacking the effects of socialization programs on newcomer retention: A meta-analytic review of field experiments. Psychological Bulletin, 150(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., & Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., & Peng, Y. (2019). The performance costs of illegitimate tasks: The role of job identity and flexible role orientation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, M. J., Christian, J. S., Burgess, R. V., & Leigh, A. (2023). Preventing success: How a prevention focus causes leaders to overrule good ideas and reduce team performance gains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(7), 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C., Balaji, P., Crilly, D., & Liu, Y. (2024). Better safe than sorry: CEO regulatory focus and workplace safety. Journal of Management, 50(4), 1453–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X., Huang, M., Hu, Q., Schminke, M., & Ju, D. (2018). Ethical leadership, but toward whom? How moral identity congruence shapes the ethical treatment of employees. Human Relations, 71(8), 1120–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassenberg, K., & Hamstra, M. R. W. (2017). The intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics of self-regulation in the leadership process. In J. M. Olson (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 193–257). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y., Wang, H. J., Jiang, L., De Witte, H., & Long, L. (2024). Tasks at hand or more challenges: The roles of regulatory focus and job insecurity in predicting work behaviours. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(4), 1632–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncdogan, A., & Dogan, I. C. (2019). Managers’ regulatory focus, temporal focus and exploration–exploitation activities. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncdogan, A., Van Den Bosch, F., & Volberda, H. (2015). Regulatory focus as a psychological micro-foundation of leaders’ exploration and exploitation activities. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, D., & Kluger, A. N. (2004). Feedback sign effect on motivation: Is it moderated by regulatory focus? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(1), 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Jiao, H., & Song, J. (2023). Wear glasses for supervisors to discover the beauty of subordinates: Supervisor developmental feedback and organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Business Research, 158(3), 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Xie, H., Xiao, C., Zheng, Y., Bao, G., & Hong, J. (2024). Different developmental feedback, same employee performance improvement: The role of job crafting and supervisor social support. Current Psychology, 43(17), 15826–15842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. B., Yan, M., Wu, H. B., Li, J. R., & Wang, X. H. (2019). Hostile retaliation or identity motivation? The mechanisms of how newcomers’ role organizational socialization affects their workplace ostracism. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(1), 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship behavior and in-role behavior. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Y., Li, W., & Lang, Y. (2019). Regulatory focus in leadership research: From the perspective of paradox theory. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(4), 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Wang, H., & Zheng, J. (2024). Linking supervisor developmental feedback to in-role performance: The role of job control and perceived rapport with supervisors. Journal of Management & Organization, 30(2), 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z., Ren, H., & Wang, S. (2024). How do regulatory focus and the big five relate to work-domain risk-taking? Evidence from resting-state fMRI. Journal of Business and Psychology, 39(4), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. (2003). When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H. Y., Wang, H. J., Sheng, Z., Liu, W., & Jiang, F. (2024). When is more (not) better? On the relationships between the number of information ties and newcomer assimilation and learning. Human Resource Management Journal, 34(4), 1080–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULMC model | 99.443 | 58 | 1.715 | 0.969 | 0.970 | 0.056 | 0.053 |

| Four-factor model | 110.967 | 59 | 1.881 | 0.961 | 0.962 | 0.055 | 0.059 |

| Three-factor model | 498.913 | 62 | 8.047 | 0.675 | 0.679 | 0.142 | 0.167 |

| Two-factor model | 902.337 | 64 | 14.099 | 0.377 | 0.383 | 0.186 | 0.228 |

| One-factor model | 1086.898 | 65 | 16.722 | 0.240 | 0.248 | 0.205 | 0.250 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Supervisor prevention focus | (0.832) | |||

| 2. Supervisor promotion focus | 0.166 ** | (0.761) | ||

| 3. Supervisor developmental feedback | −0.134 * | 0.128 * | (0.880) | |

| 4. Newcomer task performance | −0.105 | 0.017 | 0.163 ** | (0.794) |

| M | 3.646 | 4.650 | 4.885 | 4.972 |

| SD | 0.785 | 0.490 | 1.063 | 0.660 |

| Supervisor Developmental Feedback | Newcomer Task Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Gender similarity | 0.300 * | 0.300 * | −0.056 | −0.091 |

| Education similarity | 0.297 ** | 0.243 *** | −0.045 | −0.093 |

| Age similarity | −0.000 | −0.017 | −0.004 | −0.010 |

| Work tenure similarity | 0.017 | 0.035 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| Supervisor prevention focus | −0.195 * | −0.085 | ||

| Supervisor promotion focus | 0.290 ** | 0.035 | ||

| Supervisor developmental feedback | 0.113 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.075 | 0.105 | 0.005 | 0.050 |

| ΔR2 | - | 0.030 | - | 0.045 |

| F | - | 4.115 * | - | 3.861 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Chao, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, G.; Wang, M. The Trickle-Down Effects of Supervisor Regulatory Foci on Newcomer Task Performance. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020188

Zhao J, Chao W, Zhang H, Zhao G, Wang M. The Trickle-Down Effects of Supervisor Regulatory Foci on Newcomer Task Performance. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Junzhe, Wenfan Chao, Hang Zhang, Guoxiang Zhao, and Minghui Wang. 2025. "The Trickle-Down Effects of Supervisor Regulatory Foci on Newcomer Task Performance" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020188

APA StyleZhao, J., Chao, W., Zhang, H., Zhao, G., & Wang, M. (2025). The Trickle-Down Effects of Supervisor Regulatory Foci on Newcomer Task Performance. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020188