Research on the Impact of an AI Voice Assistant’s Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on User Self-Disclosure in Chinese Postpartum Follow-Up Phone Calls

Abstract

:1. Introduction

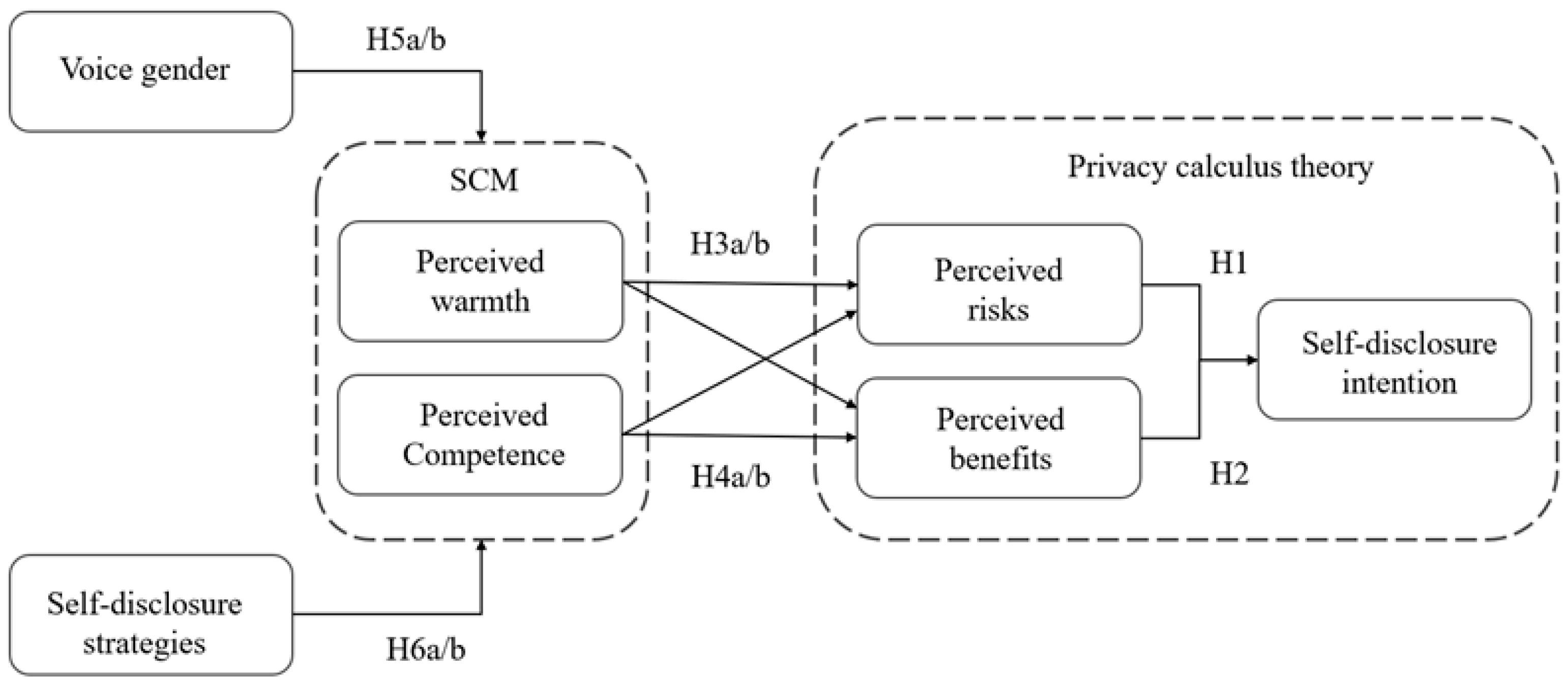

2. Related Research and Hypotheses

2.1. Self-Disclosure: Privacy Calculus Theory

2.2. Stereotype Content Model

2.3. Stereotype of Voice Gender

2.4. The Self-Disclosure Strategy of AI Affects Stereotypes

3. Methods and Procedure

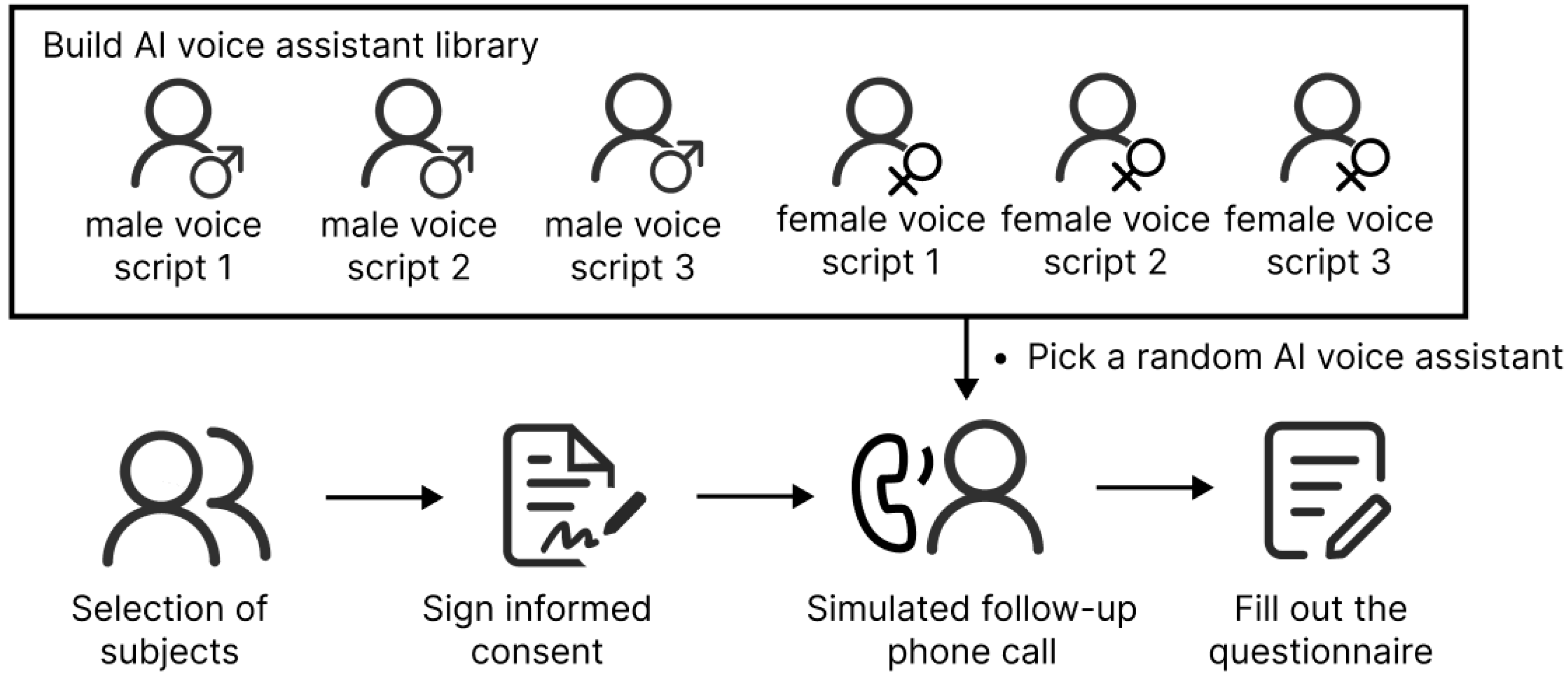

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Material Design

3.2.1. Experimental Content Design

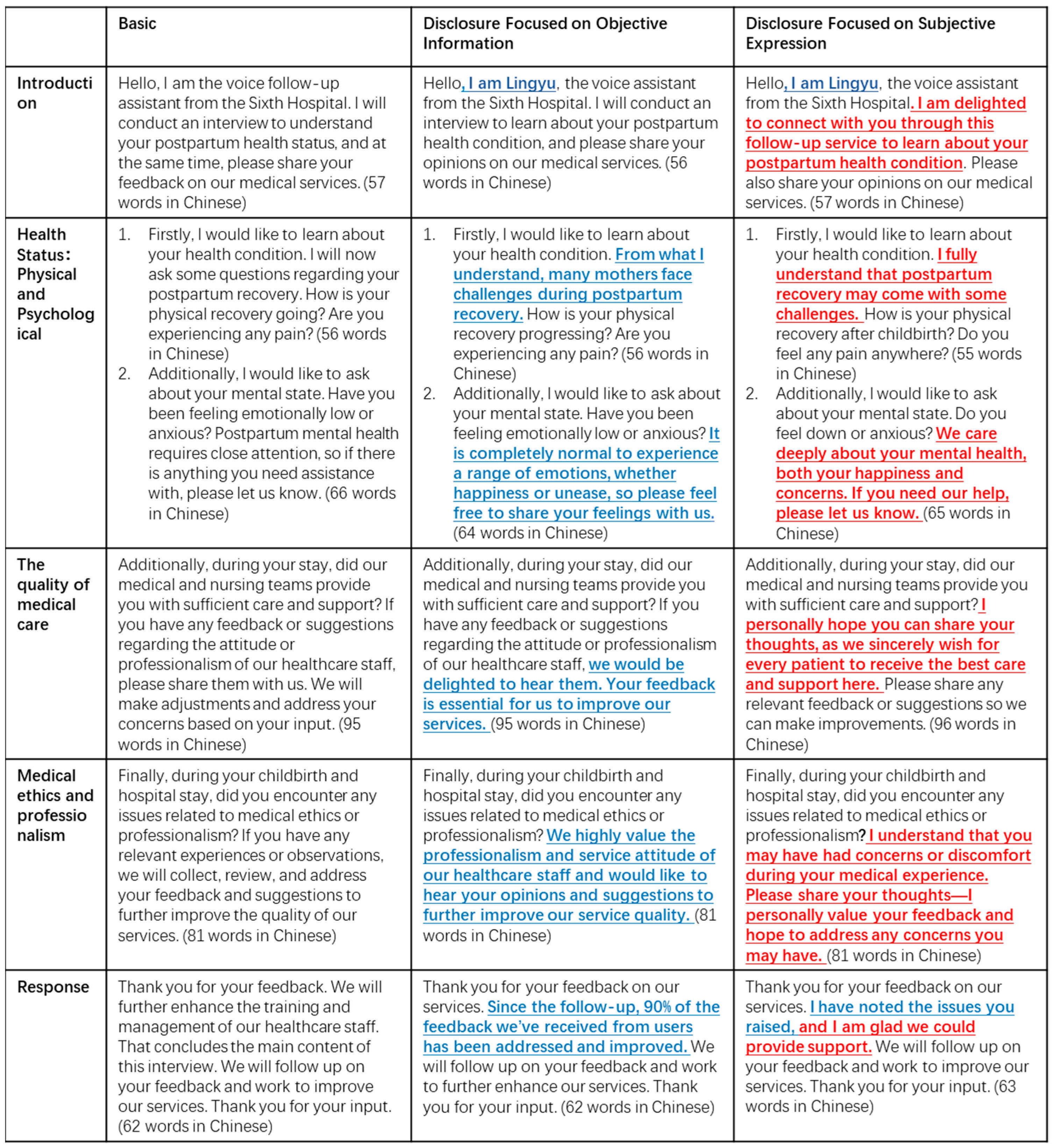

3.2.2. Reciprocal Self-Disclosure Manipulation

3.2.3. Variable Measurement

3.3. Experiment Process

4. Result

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

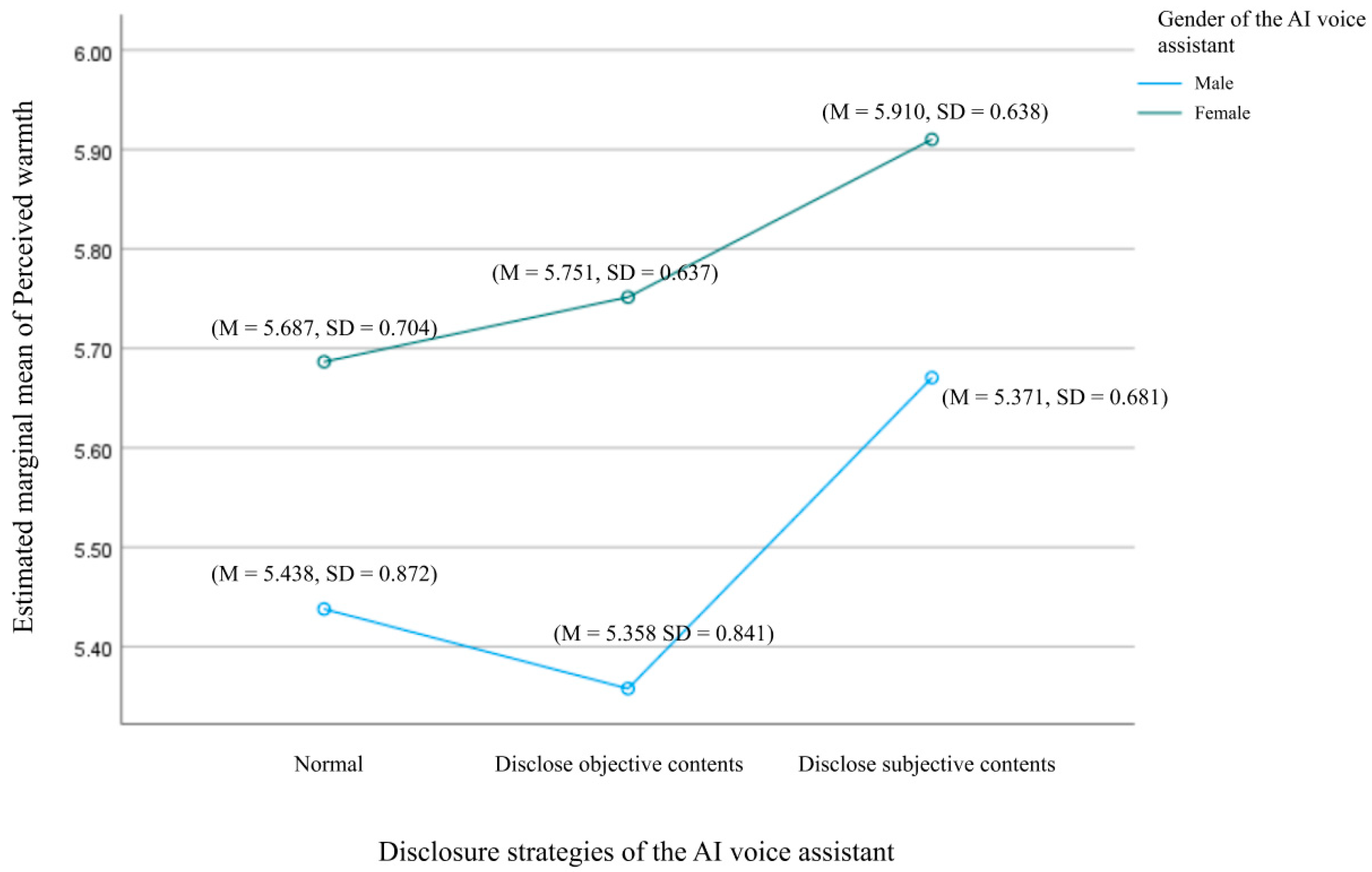

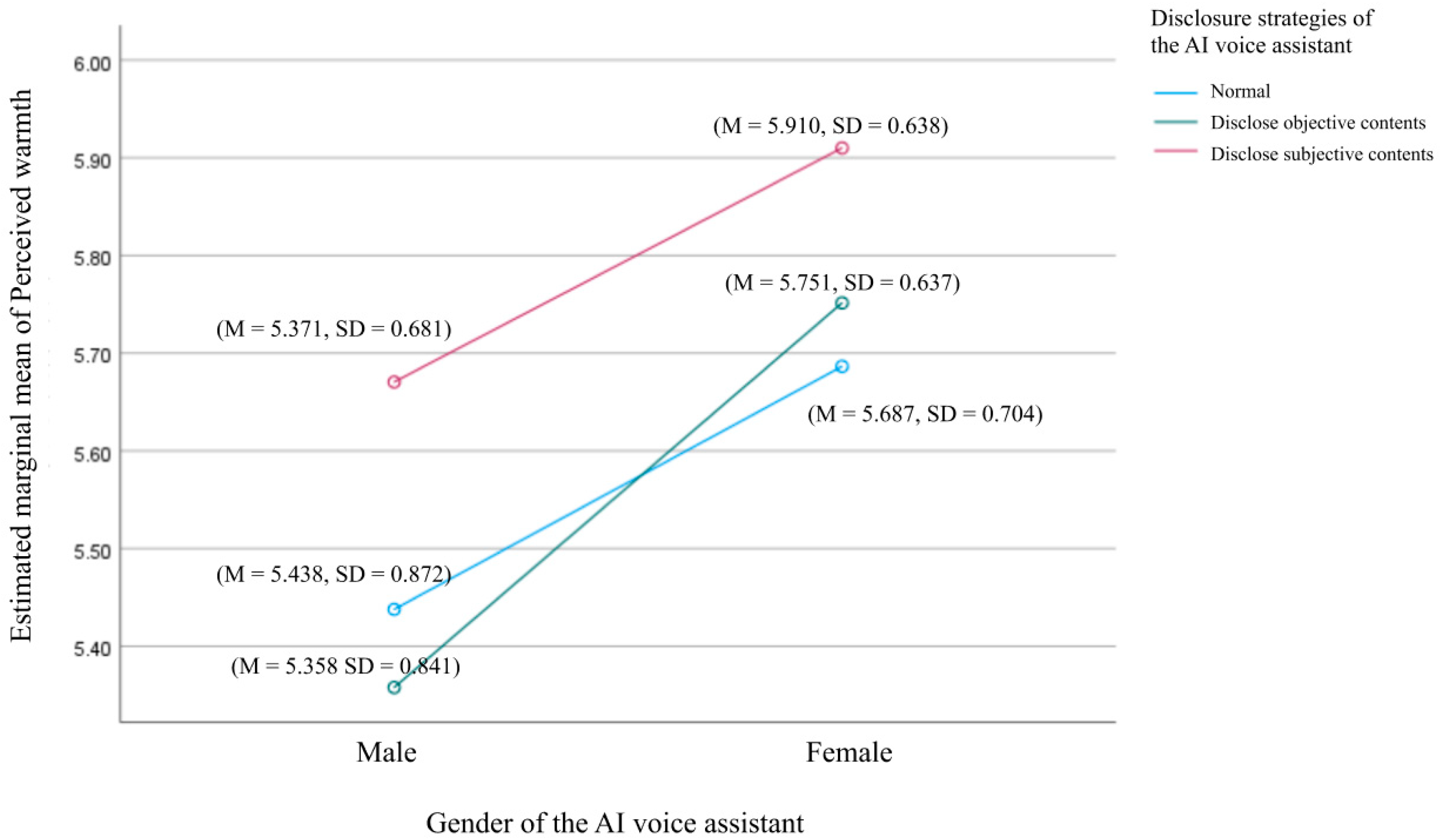

4.2. The Effect of Voice Assistant Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on Perceived Warmth Descriptive

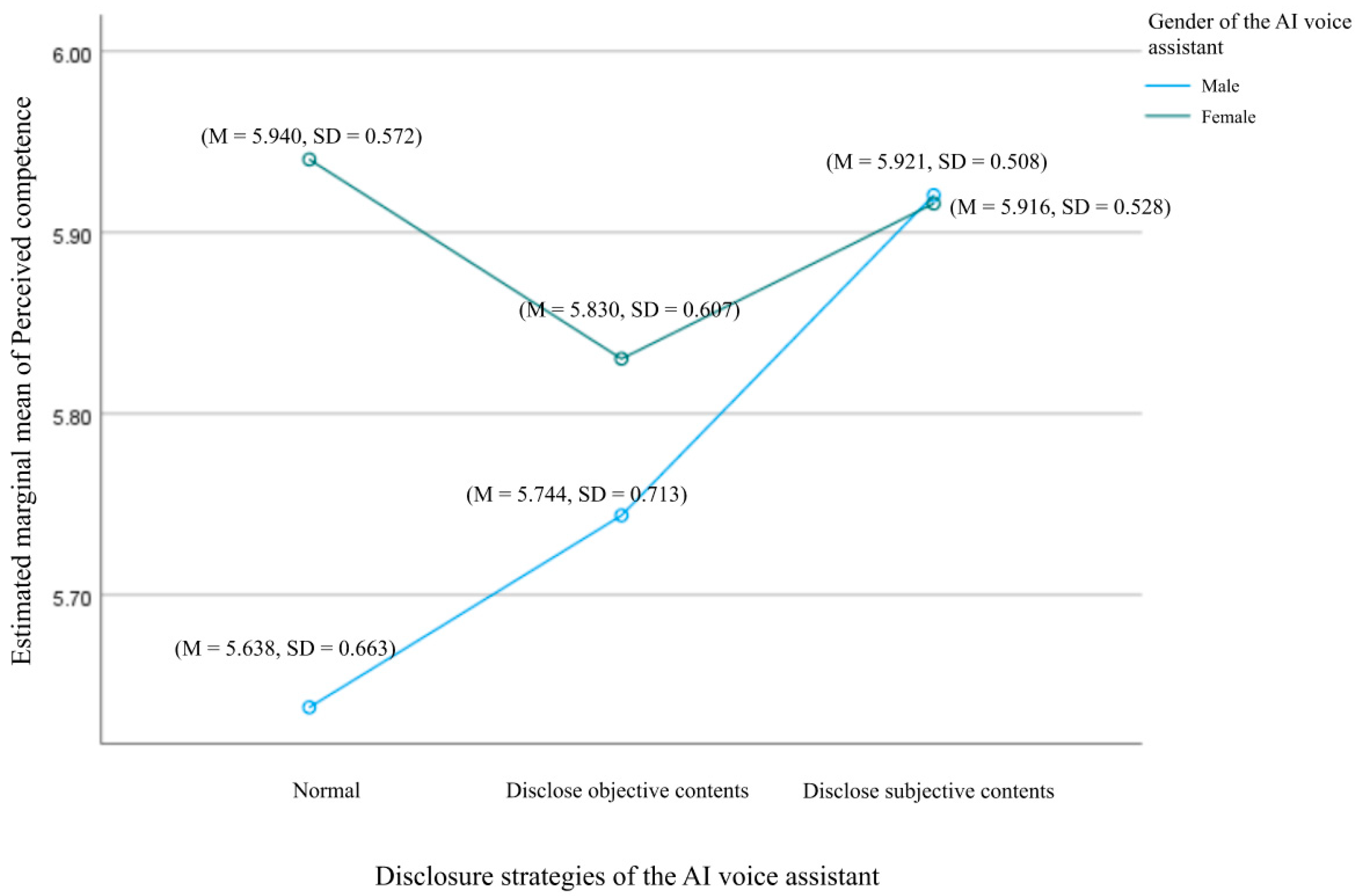

4.3. The Effect of Voice Assistant Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on Perceived Competence

4.4. The Direct Effects of Voice Assistant Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on Other Variables

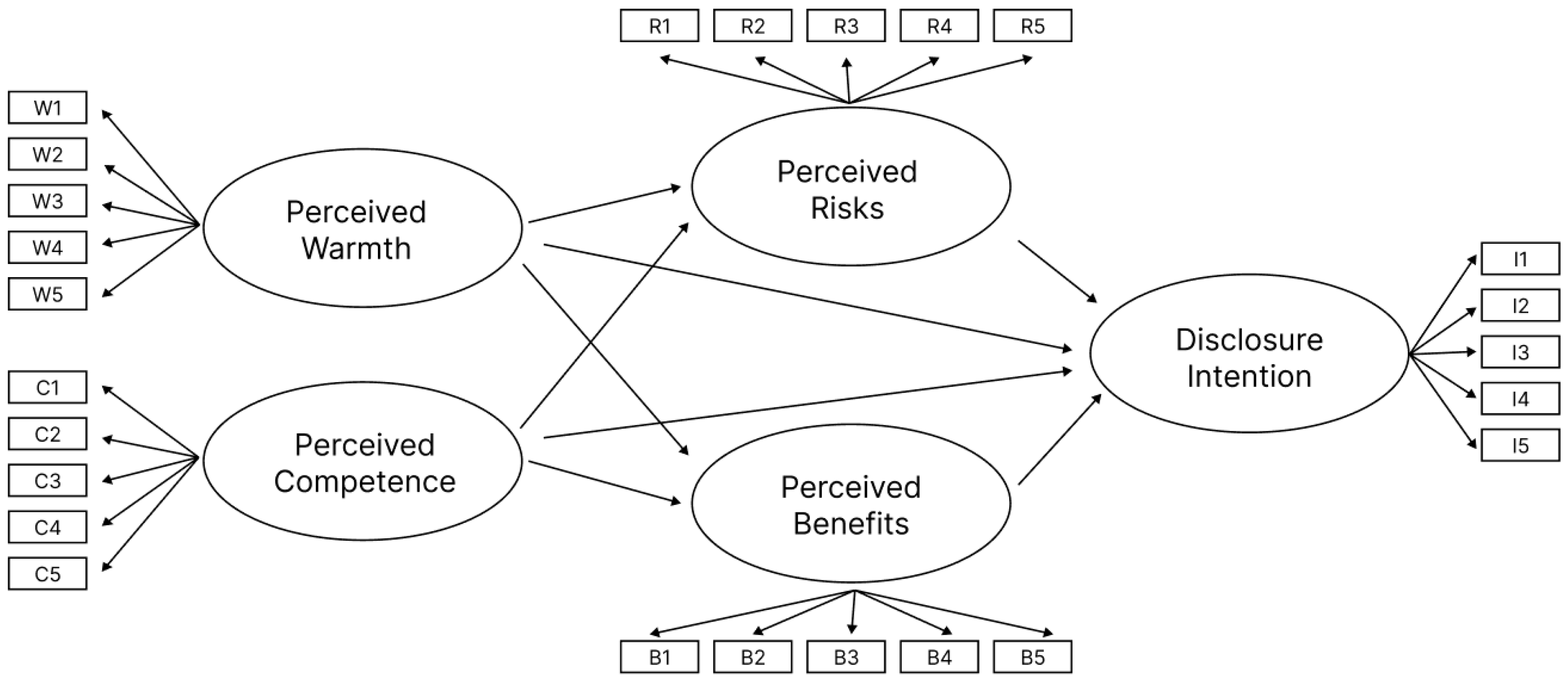

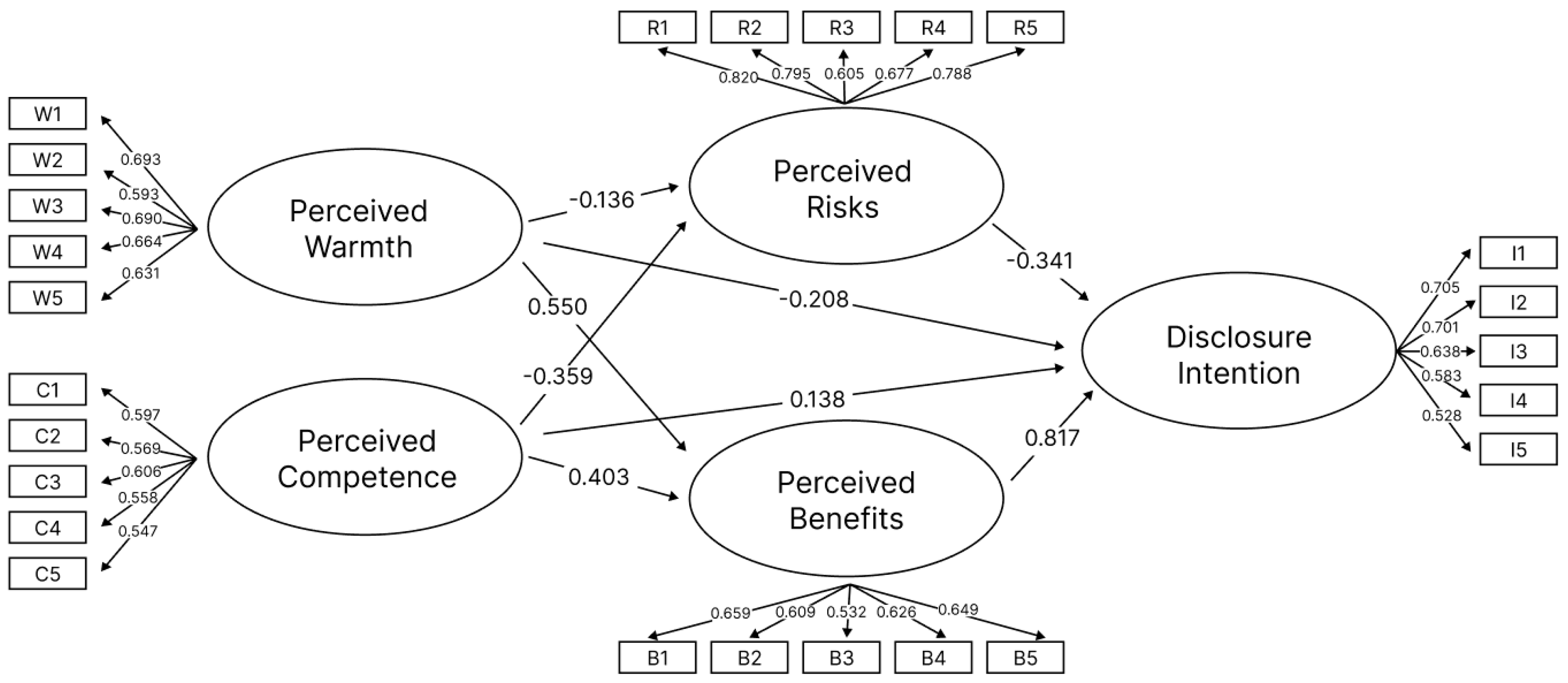

4.5. Use Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to Analyze the Relationship Between Stereotypes, Privacy Calculus, and Disclosure Intention

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Significance

5.2.1. Academic Value

5.2.2. Practical Value

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Rating Scheme for Self-Disclosure

Rating Scheme for Self-Disclosure (Archer & Berg, 1978)

| 自我披露种类 (Self-Disclosure Category) | 分值 (Rating) |

|---|---|

| 基础 (Base) | 1 |

| 简单易得的信息 (Simple and visible information) | 0到1 (0 to 1) |

| 态度和观点 (Attitudes and opinions) | 0到2 (0 to 2) |

| 强烈的情感,价值观和难以取得的信息 (Strong affections, basic values, and less visible information) | 0到3 (0 to 3) |

| 总计(Total) | 1到7 (1 to 7) |

Appendix B. Postpartum Follow-Up Voice Script

Appendix B.1. Postpartum Follow-Up Voice Script (In Chinese)

Appendix B.2. Postpartum Follow-Up Voice Script (In English)

Appendix C. Interview Outline

- Introduction

- 2.

- Collection of Basic Information about the Doctor

- 3.

- Implementation of Postpartum Follow-up phone calls

- 4.

- Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Postpartum Follow-up phone calls

- 5.

- Continuous Improvement and Challenges

- 6.

- Conclude the Interview and Express Gratitude

References

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1973-28661-000 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Archer, R. L., & Berg, J. H. (1978). Disclosure reciprocity and its limits: A reactance analysis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14(6), 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, Y., Carolus, A., & Wienrich, C. (2022). Privacy of AI-based voice assistants: Understanding the users’ perspective: A purposive review and a roadmap for elevating research on privacy from a user-oriented perspective. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 309–321). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G., & Gefen, D. (2010). The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information online. Decision Support Systems, 49(2), 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, W., Zadoroznyj, M., & Dane, A. (2013). The views of mothers and GPs about postpartum care in Australian general practice. BMC Family Practice, 14(1), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A., Blake-Lamb, T., Hatoum, I., & Kotelchuck, M. (2016). Women’s use of health care in the first 2 years postpartum: Occurrence and correlates. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(S1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Z. C., Wong, K. S., Lam, W. M., Wong, K. Y., & Kwok, Y. C. (2013). An exploration of postpartum women’s perspective on desired obstetric nursing qualities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(1–2), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B., Wu, Y., Yu, J., & Land, L. (2018). Love at First Sight: The interplay between privacy dispositions and privacy calculus in online social connectivity management. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 19(3), 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloarec, J. (2020). The personalization–privacy paradox in the attention economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M. J., & Armstrong, P. K. (1999). Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: An empirical investigation. Organization Science, 10(1), 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T., Hoit, G., Burns, D., Higgins, J., Chang, J., Whelan, D., Kiroplis, I., & Chahal, J. (2023). Use of an artificial intelligence conversational agent (Chatbot) for hip arthroscopy patients following surgery. Arthroscopy Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, 5(2), e495–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, C.-P. H., Herm-Stapelberg, N., Association for Information Systems & AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). (2020). The impact of gender stereotyping on the perceived likability of virtual assistants. AMCIS 2020 Proceedings, 4. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/326836357.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Esposito, A., Amorese, T., Cuciniello, M., Riviello, M. T., Esposito, A. M., Troncone, A., Torres, M. I., Schlögl, S., & Cordasco, G. (2019). Elder user’s attitude toward assistive virtual agents: The role of voice and gender. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 12(4), 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z. (2023). Research on measurement and psychological formation mechanism of professional stigma in contemporary Chinese doctors [Doctoral dissertation, Changchun University of Traditional Chinese Medicine]. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2006). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, C. D., & Singer, T. (2008). The role of social cognition in decision making. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1511), 3875–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J., Bian, X., Zhang, H., & Pian, X. (2011). Intervention impact of phone follow-up on hospital quality promotion. Chinese Hospitals, 15(9), 38–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, J., Buxmann, P., & Dinev, T. (2019). “They’re all the same!” stereotypical thinking and systematic errors in users’ privacy-related judgments about online services. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 20(6), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Herkes, F., Leistikow, I., Verkroost, J., De Vries, F., & Zijlstra, W. G. (2019). Can decision transparency increase citizen trust in regulatory agencies? Evidence from a representative survey experiment. Regulation & Governance, 15(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A. A., Paliwoda, M., Dawson, J., Walker, K., & New, K. (2022). Women’s utilisation, experiences and satisfaction with postnatal follow-up care. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 22(4), 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, S. M., Boyce, R. D., Ligons, F. M., Perera, S., Nace, D. A., & Hochheiser, H. (2013). Use and perceived benefits of mobile devices by physicians in preventing adverse drug events in the nursing home. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(12), 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, O., & Rögner, K. (2022, August 29–September 2). Let me introduce myself-using self-disclosure as a social cue for health care robots. 2022 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (pp. 1358–1364), Napoli, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A., Hancock, J., & Miner, A. S. (2018). Psychological, relational, and emotional effects of self-disclosure after conversations with a chatbot. Journal of Communication, 68(4), 712–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, T., Nihei, M., Inoue, T., Sugawara, I., & Kamata, M. (2022). Eliciting a user’s preferences by the self-disclosure of socially assistive robots in local households of older adults to facilitate verbal human–robot interaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M. Z., & Campbell, A. G. (2021). From luxury to necessity: Progress of touchless interaction technology. Technology in Society, 67, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, B. W., Bickmore, T., Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L., Reichert, M., Julce, C., Sidduri, N., Martin-Howard, J., Zhang, Z., Woodhams, E., Fernandez, J., Loafman, M., & Cabral, H. J. (2020). Improving the health of young African American women in the preconception period using health information technology: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Digital Health, 2(9), e475–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P. (2020). The stereotype content model as an explanation of biased perceptions in a medical interaction: Implications for Patient-Provider relationship. Health Communication, 37(1), 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S. V., & Youn, S. (2021). Why do consumers with social phobia prefer anthropomorphic customer service chatbots? Evolutionary explanations of the moderating roles of social phobia. Telematics and Informatics, 62, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M., Thompson, S., Hale, J., & Greer, C. (2012). Examining the rationality of location data disclosure through mobile devices. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2012/proceedings/ISSecurity/8/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Kim, S. Y., Schmitt, B. H., & Thalmann, N. M. (2019). Eliza in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Marketing Letters, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2024). AI health counselor’s self-disclosure: Its impact on user responses based on individual and cultural variation. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzban, R., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2001). Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(26), 15387–15392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, N. J., Hughes, K. R., Bowyer, M. D., Waters, L. T., & Bourne, V. T. (1976). Speaker sex identification from voiced, whispered, and filtered isolated vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 59(3), 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, R. S., & Wolfe, M. (1977). Privacy as a concept and a social issue: A multidimensional developmental theory. Journal of social Issues, 33(3), 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Sarathy, R., & Xu, H. (2011). The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decision Support Systems, 51(3), 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Guo, F., Ren, Z., & Wang, X. (2023). Users’ affective preference for humanoid robot in service area and its relations with voice acoustic parameters. Industrial Engineering and Management, 28(6), 145–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. (2016). Effect analysis of maternal character, pregnancy timing and mode of delivery on postpartum depression. Chinese Medical Sciences, 6(10), 60–63. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, G. M., Gratch, J., King, A., & Morency, L. P. (2014). It’s only a computer: Virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. V., Peterson, B. D., Costa, P., Costa, M. E., Lund, R., & Schmidt, L. (2013). Interactive effects of social support and disclosure on fertility-related stress. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(4), 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Nachshon, O. (1991). Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. (2000). Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C., Moon, Y., & Green, N. (1997). Are machines gender neutral? Gender-stereotypic responses to computers with voices. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(10), 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painuly, S., Sharma, S., & Matta, P. (2023, March 23–25). Artificial intelligence in e-healthcare supply chain management system: Challenges and future trends. 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS) (pp. 569–574), Erode, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I., Hancock, T., & Xie, T. (2022). Exploring relationship development with social chatbots: A mixed-method study of replika. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, M., Campbell, O. M., & Woodd, S. L. (2024). Current approaches to following up women and newborns after discharge from childbirth facilities: A scoping review. Global Health Science and Practice, 12(2), e2300377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietraszewski, D., Curry, O. S., Petersen, M. B., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2015). Constituents of political cognition: Race, party politics, and the alliance detection system. Cognition, 140, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post Discharge Follow-Up Phone Call Documentation Form. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/red/toolkit/redtool5.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Roter, D. L., & Hall, J. A. (1987). Physicians’ interviewing styles and medical information obtained from patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2(5), 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarizadeh, K., Keil, M., Boodraj, M., & Alashoor, T. (2024). “My name is alexa. what’s your name?” The impact of reciprocal self-disclosure on post-interaction trust in conversational agents. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 25(3), 528–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetzler, R. M., Grimes, G. M., Giboney, J. S., & Nunamaker, J. F., Jr. (2018, January 3–6). The influence of conversational agents on socially desirable responding. 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (p. 283), Waikoloa Village, HI, USAAvailable online: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/isqafacpub/61 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Sezgin, E., Huang, Y., Ramtekkar, U., & Lin, S. (2020). Readiness for voice assistants to support healthcare delivery during a health crisis and pandemic. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S., Treger, S., Wondra, J. D., Hilaire, N., & Wallpe, K. (2013). Taking turns: Reciprocal self-disclosure promotes liking in initial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(5), 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F., Wang, Y., Wu, Q., Wang, P. J., & Chang, X. (2022). The influence of stereotypes on trust in doctors from patients’ perspective: The mediating role of communication. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 3663–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, B., Im, H., & Duong, V. C. (2023). Task type’s effect on attitudes towards voice assistants. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(5), 1772–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, T., Hewstone, M., Harwood, J., Voci, A., & Kenworthy, J. (2006). Intergroup contact and grandparent–grandchild communication: The effects of self-disclosure on implicit and explicit biases against older people. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9(3), 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D., & Zhang, S. (2023). The research status and implications of medical insurance impact on neonatal health in a low-fertility setting. Chinese Health Economics, 42(6), 26–29, 39. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Traunmüller, H., & Eriksson, A. (1995). The frequency range of the voice fundamental in the speech of male and female adults [Unpublished manuscript]. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=dcf068d9e9604d7266152b620f1c5dfa7fa45349 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Umar, N., Hill, Z., Schellenberg, J., Tuncalp, Ö., Muzigaba, M., Sambo, N. U., Shuaibu, A., & Marchant, T. (2023). Women’s perceptions of telephone interviews about their experiences with childbirth care in Nigeria: A qualitative study. PLoS Global Public Health, 3(4), e0001833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vcbeat. (2024). 2024 Medical Artificial Intelligence Report: Generative AI explodes and medical AI comes to a new crossroads. Available online: https://www.vbdata.cn/reportCard/72385 (accessed on 17 January 2025). Available online.

- Vogel, D. L., & Wester, S. R. (2003). To seek help or not to seek help: The risks of self-disclosure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(3), 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Wang, D., Tian, F., Peng, Z., Fan, X., Zhang, Z., Yu, M., Ma, X., & Wang, H. (2021). CASS: Towards building a social-support chatbot for online health community. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Duong, T. D., & Chen, C. C. (2016). Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy calculus perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 36(4), 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., & Liao, Z. (2021). Health privacy information self-disclosure in online health community. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 602792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F., Hang, S., Ju, Y., & Wang, J. (2023). Cross-category Stereotype Content between Intimate Relationship Status and Gender. Chinese Social Psychology Review, 24, 66–90. Available online: https://xianxiao.ssap.com.cn/catalog/6739960.html (accessed on 1 July 2024). (In Chinese).

- Wheeless, L. R., & Grotz, J. (1976). Conceptualization and measurement of reported self-disclosure. Human Communication Research, 2(4), 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. (2023). Effectiveness of follow up phone calls on postpartum women after discharge: A program evaluation [Doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri-Saint Louis]. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/9bd3b9abcf8f6bb08e5d971cb58f0a8d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Wojciszke, B., Bazinska, R., & Jaworski, M. (1998). On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C. E., Jones, R., O’Shea, E., Grist, E., Wiggers, J., & Usher, K. (2019). Nurse-led postdischarge telephone follow-up calls: A mixed study systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(19–20), 3386–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Teo, H. H., Tan, B. C., & Agarwal, R. (2009). The role of push-pull technology in privacy calculus: The case of location-based services. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3), 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. (2009). Analysis on the satisfaction of discharged patients by telephone follow-up. Journal of Nursing Science, 24(1), 62–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Wang, S., & Chen, L. (2021). The application of intelligent speech technology in electronic medical records of outpatient. China Digital Medicine, 16(8), 12–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, S., Chen, X., Wang, L., Gao, B., & Zhu, Q. (2017). Health information privacy concerns, antecedents, and information disclosure intention in online health communities. Information & Management, 55(4), 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Ye, Y., Cao, X., Liu, Y., Peng, B., & Zhu, K. (2024). Maternal health care services in primary medical institutions in six regionally representative provinces of China, 2021: A submitted data-based analysis. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 40(2), 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. (2024). Gender stereotypes and mental health among Chinese people: The moderating role of marital status. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. (2017). Research progress of multiple postpartum visits. World Latest Medicine Information (CD-ROM), 17(30), 36–38. Available online: https://med.wanfangdata.com.cn/Paper/Detail?id=PeriodicalPaper_sjzxyy-e201730016&dbid=WF_QK (accessed on 17 July 2024). (In Chinese).

| Variable Name | Measurement Item | Original Statement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Warmth | 1. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is friendly. | 1. Friendly | (Sung et al., 2023; Cuddy et al., 2008) |

| 2. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is trustworthy | 2. Trustworthy | ||

| 3. I feel the voice assistant in the telephone follow-up is good-natured. | 3. Good-natured | ||

| 4. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is warm. | 4. Warm | ||

| 5. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is sincere. | 5. Sincere | ||

| Perceived Competence | 1. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is competent. | 1. Competent | (Sung et al., 2023; Cuddy et al., 2008) |

| 2. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is confident. | 2. Confident | ||

| 3. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is intelligent. | 3. Intelligent | ||

| 4. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is efficient. | 4. Efficient | ||

| 5. I feel the voice assistant in the follow-up phone call is skilful. | 5. Skilful | ||

| Perceived Risks | 1. The likelihood of information provided during the follow-up phone call causing risks is high. | 1. The likelihood expected problems is high | (H. Li et al., 2011) |

| 2. Disclosing information during the follow-up phone call has a high potential for loss. | 2. The potential for loss would be high | (T. Wang et al., 2016) | |

| 3. I believe disclosing private information during the follow-up phone call is inadvisable. | 3. I believe that submitting information is not advisable at all | (X. Zhang et al., 2017) | |

| 4. If my private information is invaded during the follow-up phone call, the consequences would be significant. | 4. If my information privacy is invaded, it would be significant | ||

| 5. The follow-up phone call poses a risk of invading my private information. | 5. My information privacy is at risk of being invaded | ||

| Perceived Benefits | 1. Providing information during the follow-up phone call enables me to receive advice when I need help. | 1. Some people would offer suggestions when l needed help | (X. Zhang et al., 2017) |

| 2. Providing information during the follow-up phone call helps me overcome challenges when I encounter problems. | 2. When l encountered a problem, some people would give me information to help me overcome the problem | ||

| 3. Disclosing information during the follow-up phone call ensures that the follow-up personnel stand by my side when I face difficulties. | 3. When faced with difficulties, some people are on my side with me | ||

| 4. Providing information during the follow-up phone call shows the follow-up personnel’s interest and concern for my health and well-being. | 4. When faced with difficulties, some people expressed interest and concern in my wellbeing | ||

| 5. Overall, I feel that providing information during the follow-up phone call is beneficial. | 5. Overall, I feel that it is beneficial | (T. Wang et al., 2016) | |

| Self-Disclosure Intention | 1. I intend to provide information during the follow-up phone call. | 1. Probable/Not probable | (Bansal & Gefen, 2010) (T. Wang et al., 2016; X. Zhang et al., 2017) |

| 2. I am willing to provide information during the follow-up phone call. | 2. Willing/Unwilling | ||

| 3. I will continue to disclose information in future follow-up phone calls. | 3. Keep reveal | ||

| 4. My self-disclosure during the follow-up phone call accurately reflects my thoughts. | 4. When I wish, my self-disclosures are always accurate reflections of who I really am. | (Wheeless & Grotz, 1976) | |

| 5. When I disclose information about myself during the follow-up phone call, I do so consciously and intentionally. | 5. When I reveal my feelings about myself, I consciously intend to do so. |

| Factors | Variable | NSlF | SLF | z | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth | w1 | 1 | 0.693 | - | - | - |

| w2 | 0.754 | 0.593 | 10.28 | 0.073 | <0.01 | |

| w3 | 1.174 | 0.690 | 11.758 | 0.100 | <0.01 | |

| w4 | 1.291 | 0.664 | 11.384 | 0.113 | <0.01 | |

| w5 | 0.861 | 0.631 | 10.870 | 0.079 | <0.01 | |

| Competence | c1 | 1 | 0.597 | - | - | - |

| c2 | 1.048 | 0.569 | 8.687 | 0.121 | <0.01 | |

| c3 | 1.147 | 0.606 | 9.099 | 0.126 | <0.01 | |

| c4 | 0.942 | 0.558 | 8.562 | 0.110 | <0.01 | |

| c5 | 0.847 | 0.547 | 8.445 | 0.100 | <0.01 | |

| Risks | r1 | 1 | 0.820 | - | - | - |

| r2 | 0.974 | 0.795 | 16.791 | 0.058 | <0.01 | |

| r3 | 0.997 | 0.605 | 12.08 | 0.083 | <0.01 | |

| r4 | 1.049 | 0.677 | 13.791 | 0.076 | <0.01 | |

| r5 | 0.992 | 0.788 | 16.616 | 0.060 | <0.01 | |

| Benefits | b1 | 1 | 0.659 | - | - | - |

| b2 | 1.103 | 0.609 | 10.424 | 0.106 | <0.01 | |

| b3 | 1.152 | 0.532 | 9.256 | 0.124 | <0.01 | |

| b4 | 1.163 | 0.626 | 10.666 | 0.109 | <0.01 | |

| b5 | 1.069 | 0.649 | 11.004 | 0.097 | <0.01 | |

| Intention | i1 | 1 | 0.705 | - | - | - |

| i2 | 1.017 | 0.701 | 12.573 | 0.081 | <0.01 | |

| i3 | 1.001 | 0.638 | 11.506 | 0.087 | <0.01 | |

| i4 | 0.863 | 0.583 | 10.542 | 0.082 | <0.01 | |

| i5 | 0.827 | 0.528 | 9.589 | 0.086 | <0.01 |

| Effects | B | SE | z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| warmth | → | risks | −0.136 | 0.167 | −1.221 | 0.222 |

| competence | → | risks | −0.359 | 0.226 | −3.036 | <0.01 |

| warmth | → | benefits | 0.550 | 0.082 | 5.437 | <0.01 |

| competence | → | benefits | 0.403 | 0.105 | 3.983 | <0.01 |

| risks | → | intention | −0.341 | 0.033 | −6.740 | <0.01 |

| benefits | → | intention | 0.817 | 0.232 | 4.272 | <0.01 |

| warmth | → | intention | −0.208 | 0.138 | −1.493 | 0.135 |

| competence | → | intention | 0.138 | 0.153 | 1.136 | 0.256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Shen, T.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, B. Research on the Impact of an AI Voice Assistant’s Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on User Self-Disclosure in Chinese Postpartum Follow-Up Phone Calls. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020184

Sun X, Shen T, Jiang Q, Jiang B. Research on the Impact of an AI Voice Assistant’s Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on User Self-Disclosure in Chinese Postpartum Follow-Up Phone Calls. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020184

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xinxin, Tianyuan Shen, Qianling Jiang, and Bin Jiang. 2025. "Research on the Impact of an AI Voice Assistant’s Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on User Self-Disclosure in Chinese Postpartum Follow-Up Phone Calls" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020184

APA StyleSun, X., Shen, T., Jiang, Q., & Jiang, B. (2025). Research on the Impact of an AI Voice Assistant’s Gender and Self-Disclosure Strategies on User Self-Disclosure in Chinese Postpartum Follow-Up Phone Calls. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020184