Exploring the Impact of Workplace Hazing on Deviant Behavior in the Hospitality Sector: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Hope and Optimism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Transaction Theory of Stress

2.2. Workplace Hazing

2.3. Deviant Behaviour (Supervisor Rated)

2.4. Workplace Hazing and Deviant Behavior

2.5. Workplace Hazing and Emotional Exhaustion

2.6. Emotional Exhaustion and Deviant Behavior

2.7. The Mediation Role of Emotional Exhaustion

2.8. The Moderation Role of Hope and Optimism

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Measures

3.4. Analytical Procedures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Non-Response Bias

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB)

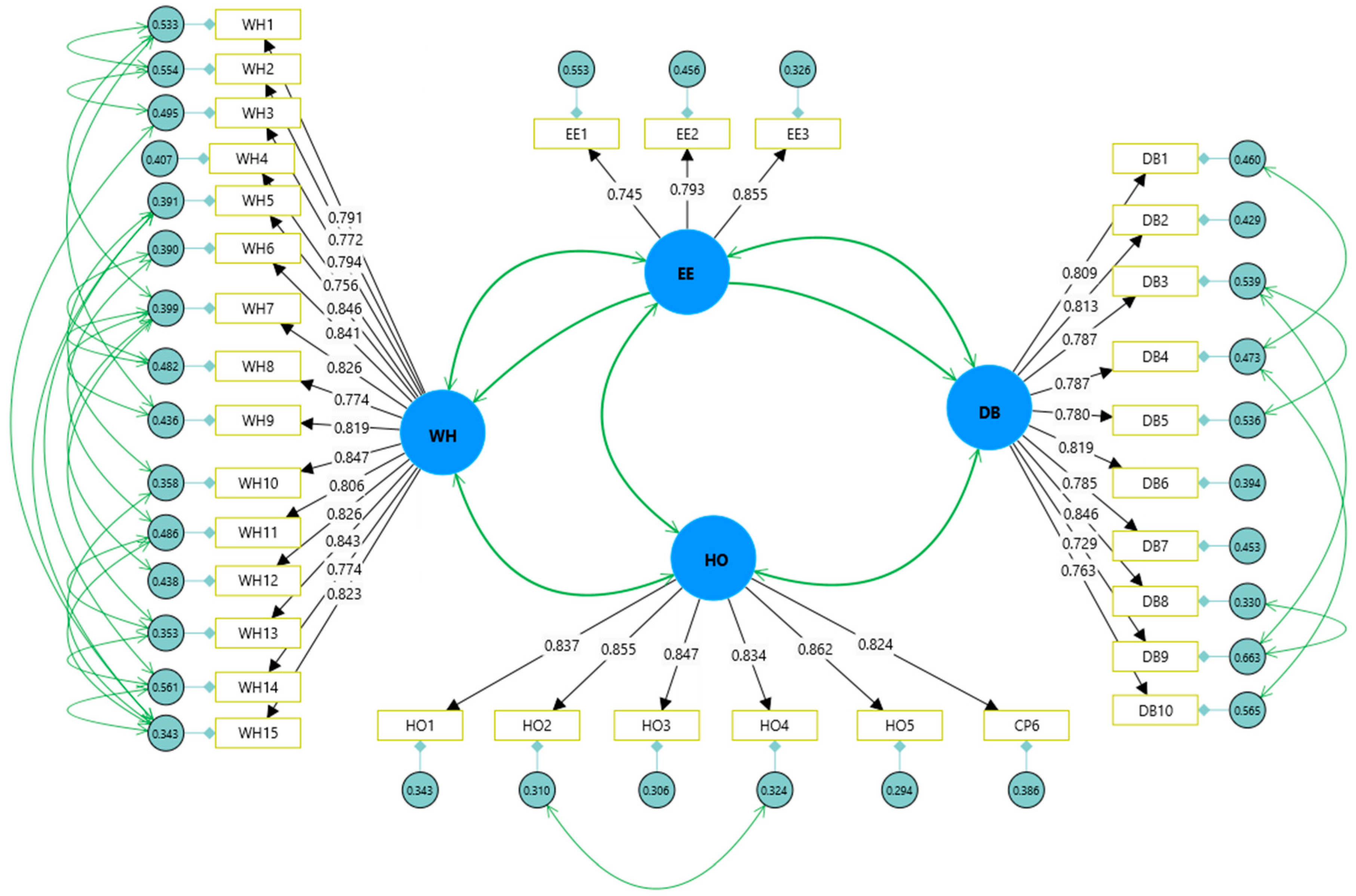

4.3. Measurement Model Validation

4.4. Mediation Model

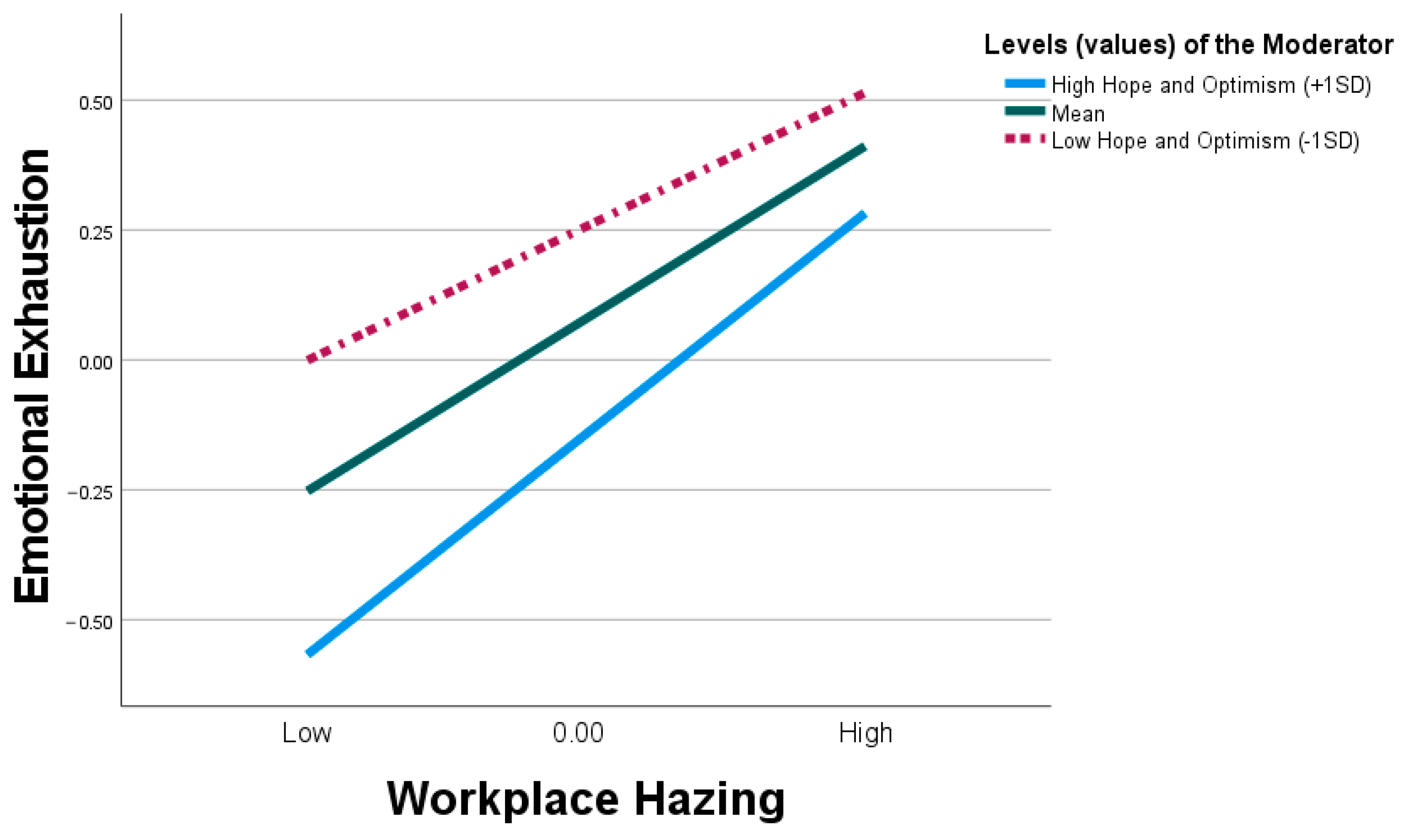

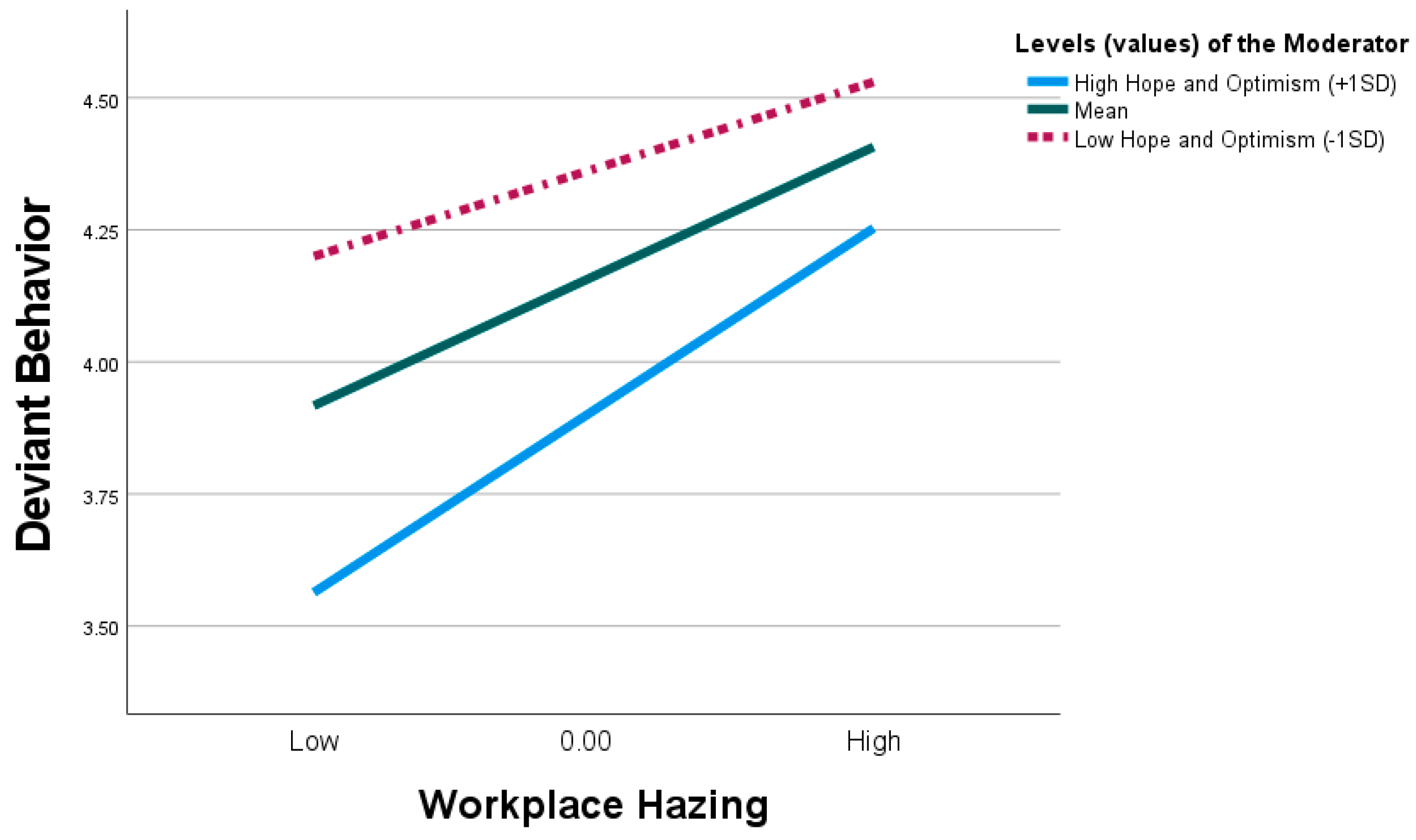

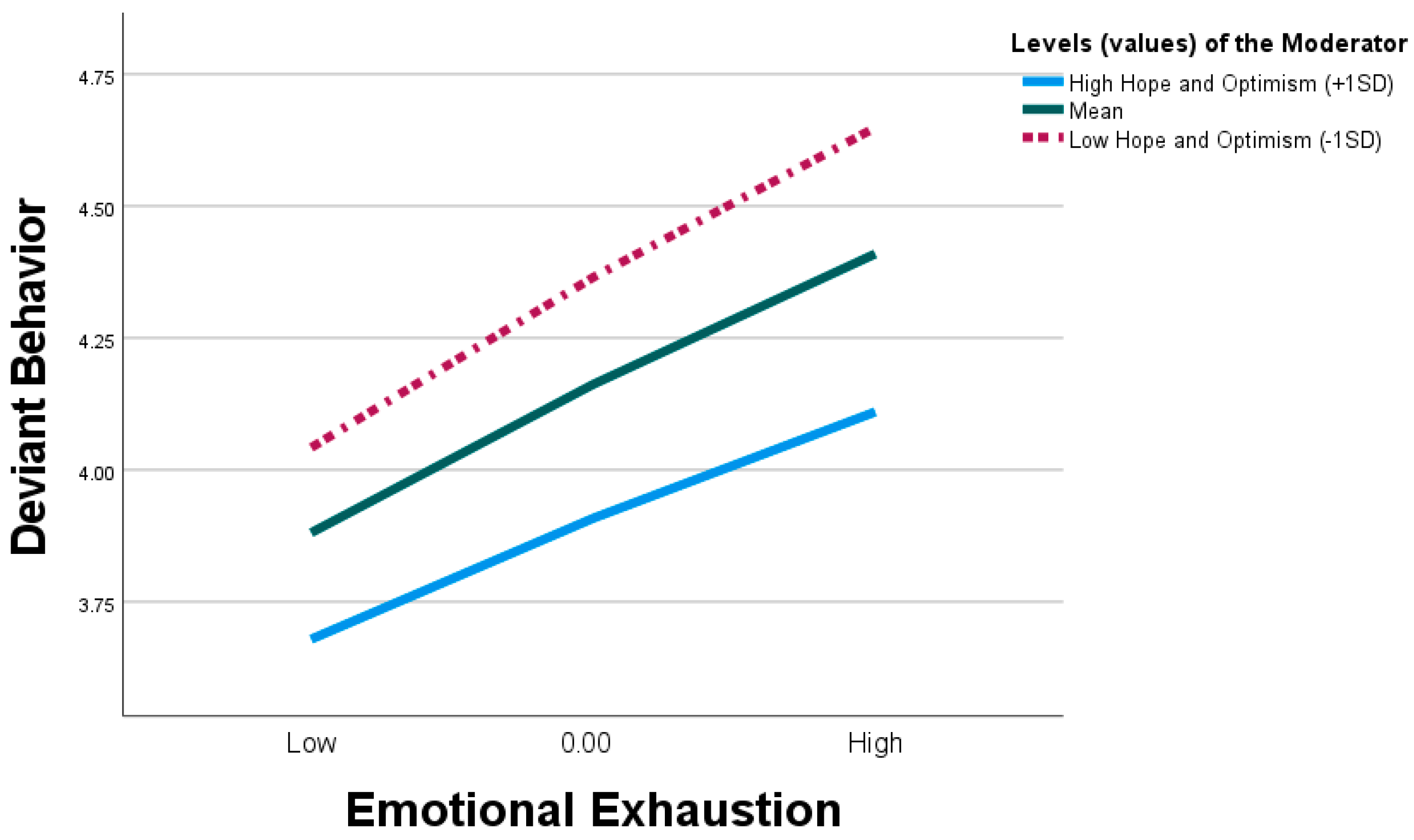

4.5. Moderated Mediation Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Workplace Hazing (Mawritz et al., 2022) |

| 1. Segregated me from our work group |

| 2. Excluded me from our work group |

| 3. Refrained from socializing with me. |

| 4. Ridiculed me. |

| 5. Verbally humiliated me. |

| 6. Verbally embarrassed me. |

| 7. Directed me to work on tasks that are not relevant to the future work I will do for the group. |

| 8. Given me unimportant tasks to complete. |

| 9. Withheld useful information from me about how to accomplish tasks. |

| 10. Physically harmed me. |

| 11. Deprived me of food. |

| 12. Gotten physically aggressive with me (shoving, slapping, hitting). |

| 13. Told me stories that are untrue to see how naive I am. |

| 14. Played pranks on me to test my gullibility. |

| 15. Told me lies to see if I am a pushover. |

| Emotional exhaustion (Boswell et al., 2004) |

| 1. I feel emotionally drained from my work |

| 2. I feel burned out from my work. |

| 3. I feel exhausted when I think about having to face another day on the job. |

| Hope and optimism (Grobler & Joubert, 2018) |

| 1. At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my work goals. |

| 2. Right now, I see myself as being pretty successful at work. |

| 3. I can think of many ways to reach my current work goals. |

| 4. At this time, I am meeting the work goals that I have set for myself |

| 5. When things are uncertain for me at work, I usually expect the best. |

| 6. I always look on the bright side of things regarding my job |

| Deviant behavior (Bennett & Robinson, 2000) |

| 1. Spent too much time fantasizing or daydreaming instead of working. |

| 2. Falsified a receipt to get reimbursed for more money than you spent on business expenses. |

| 3. Taken an additional or longer break than is acceptable at your workplace. |

| 4. Come in late to work without permission. |

| 5. Neglected to follow your boss’s instructions. |

| 6. Intentionally worked slower than you could have worked. |

| 7. Discussed confidential company information with an unauthorized person. |

| 8. Used an illegal drug or consumed alcohol on the job. |

| 9. Put little effort into your work. |

| 10. Dragged out work to get overtime. |

References

- Aboalhool, T., Alzubi, A., & Iyiola, K. (2024). Humane entrepreneurship in the circular economy: The role of green market orientation and green technology turbulence for sustainable corporate performance. Sustainability, 16(6), 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzawida, S. S., Alzubi, A. B., & Iyiola, K. (2023). Sustainable supply chain practices: An empirical investigation from the manufacturing industry. Sustainability, 15(19), 14395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. K., Atta, M. H. R., El-Monshed, A. H., & Mohamed, A. I. (2024). The effect of toxic leadership on workplace deviance: The mediating effect of emotional exhaustion, and the moderating effect of organizational cynicism. BMC Nursing, 23(1), 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L. S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M., Usman, M., Pham, N. T., Agyemang-Mintah, P., & Akhtar, N. (2020). Being ignored at work: Understanding how and when spiritual leadership curbs workplace ostracism in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Usman, M., Shafique, I., Garavan, T., & Muavia, M. (2022). Fueling the spirit of care to surmount hazing: Foregrounding the role of spiritual leadership in inhibiting hazing in the hospitality context. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(10), 3910–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tera, A., Alzubi, A., & Iyiola, K. (2024). Supply chain digitalization and performance: A moderated mediation of supply chain visibility and supply chain survivability. Heliyon, 10(4), e25584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwheshi, A., Alzubi, A., & Iyiola, K. (2024). Linking responsible leadership to organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: Examining the role of employees harmonious environmental passion and environmental transformational leadership. SAGE Open, 14(3), 21582440241271177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, E., Bayighomog, S. W., & Tanova, C. (2020). Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. The Service Industries Journal, 40(1–2), 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamkonda, N., & Pattusamy, M. (2024). Intention to stay and happiness: A moderated mediation model of work engagement and hope. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 13(1), 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, W. R., Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & LePine, M. A. (2004). Relations between stress and work outcomes: The role of felt challenge, job control, and psychological strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitsohl, J., & Garrod, B. (2016). Assessing tourists’ cognitive, emotional and behavioural reactions to an unethical destination incident. Tourism Management, 54, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyangwa, R., & Muponya, I. (2024). Investigating the role of optimism and resilience on the effect of work engagement on emotional exhaustion and workplace deviant behaviors. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 12(2), 5894–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. (2019). The moderating effect of leader member exchange on the relationship between workplace ostracism and psychological distress. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 11(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodanwala, T. C., & Shrestha, P. (2021). Work–family conflict and job satisfaction among construction professionals: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures, 29(2), 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z. (2021). The work stress of Chinese senior executives: Work stressors and coping strategies [Ph.D. thesis, Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington]. [Google Scholar]

- Dula, D. (2022). Role conflict, work-related stress, and correctional officer misconduct [Ph.D. thesis, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, H. R. (2023). Exploring the impact of stress on the management of the hotel industry: The case of a hotel in tampere [Bachelor’s Thesis, Häme University of Applied Sciences]. [Google Scholar]

- Golparvar, M., Nayeri, S., & Mahdad, A. (2008). The relationship between stress, emotional exhaustion, and organizational deviant behaviors in Zobahan Joint Stock Company: Evidence for the stress-exhaustion-compensation model. Social Psychology, 2(8), 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grobler, A., & Joubert, Y. T. (2018). Psychological Capital: Convergent and discriminant validity of a reconfigured measure. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (17th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S., Hong, W., Xu, H., Zhou, L., & Xie, Z. (2015). Relationship between resilience, stress and burnout among civil servants in Beijing, China: Mediating and moderating effect analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (methodology in the social sciences) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Ford, J. S. (2007). Conservation of resources theory. Encyclopedia of Stress, 3(3), 562–567. [Google Scholar]

- Iyiola, K., Alzubi, A., & Dappa, K. (2023). The influence of learning orientation on entrepreneurial performance: The role of business model innovation and risk-taking propensity. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3), 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K., & Rjoub, H. (2020). Using conflict management in improving owners and contractors relationship quality in the construction industry: The mediation role of trust. Sage Open, 10(1), 2158244019898834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S., & Fatima, T. (2017, August 4–9). The role of defensive and prosocial silence between workplace ostracism and emotional exhaustion. Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X., Liao, S., & Yin, W. (2022). Job insecurity, emotional exhaustion, and workplace deviance: The role of corporate social responsibility. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1000628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Jiang, X., Sun, P., & Li, X. (2021). Coping with workplace ostracism: The roles of emotional exhaustion and resilience in deviant behavior. Management Decision, 59(2), 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R., Ghaderi, Z., Elayan, M. B., Selem, K. M., Mkheimer, I. M., & Raza, M. (2024). Dark triad traits, job involvement, and depersonalization among hotel employees: The mediating role of workplace incivility. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 25(4), 764–792. [Google Scholar]

- Khliefat, A., Chen, H., Ayoun, B., & Eyoun, K. (2021). The impact of the challenge and hindrance stress on hotel employees interpersonal citizenship behaviors: Psychological capital as a moderator. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D. T., Ho, V. T., & Garg, S. (2020). Employee and coworker idiosyncratic deals: Implications for emotional exhaustion and deviant behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 164, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., & Jin, Y. (2022). Impact of nurses’ emotional labour on job stress and emotional exhaustion amid COVID-19: The role of instrumental support and coaching leadership as moderators. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(7), 2620–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D. M., & Harrington, T. C. (1990). Measuring nonresponse bias in customer service mail surveys. Journal of business Logistics, 11(2), 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, M., & Lomax, R. G. (2005). The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T., Thompson, J., Tian, L., & Beck, B. (2023). A transactional model of stress and coping applied to cyclist subjective experiences. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 96, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawritz, M. B., Capitano, J., Greenbaum, R. L., Bonner, J. M., & Kim, J. (2022). Development and validation of the workplace hazing scale. Human Relations, 75(1), 139–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, K., & Teoh, K. R. (2022). Psychological capital, future-oriented coping, and the well-being of secondary school teachers in Germany. Educational Psychology, 42(3), 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. B., Einarsen, S. V., Parveen, S., & Rosander, M. (2024). Witnessing workplace bullying—A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual health and well-being outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 75, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D. M., & Bordelon, B. M. (2022). How the# MeToo movement affected sexual harassment in the hospitality industry: A US case study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 101, 103106. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 72, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preena, R. (2021). Perceived workplace ostracism and deviant workplace behavior: The moderating effect of psychological capital. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 15(3), 476–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan, A., Iyiola, K., & Alzubi, A. B. (2024). Linking absorptive capacity to project success via mediating role of customer knowledge management capability: The role of environmental complexity. Business Process Management Journal, 30(3), 939–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., Ishaq, M. I., Jamali, D. R., Zia, H., & Haj-Salem, N. (2024). Testing workplace hazing, moral disengagement and deviant behaviors in hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(3), 743–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, H., & Tanova, C. (2021). Workplace bullying in the hospitality industry: A hindrance to the employee mindfulness state and a source of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A., & Muhammad, L. (2020). Impact of employee perceptions of mistreatment on organizational performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A., Muhammad, L., & Sigala, M. (2021). Unraveling the complex nexus of punitive supervision and deviant work behaviors: Findings and implications from hospitality employees in Pakistan. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1437–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, W., & Usmani, S. (2022). Workplace hazing and employee turnover intention: Understanding the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion. KASBIT Business Journal, 15(3), 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Si, W., Khan, N. A., Ali, M., Amin, M. W., & Pan, Q. (2023). Excessive enterprise social media usage and employee creativity: An application of the transactional theory of stress and coping. Acta Psychologica, 232, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., Madan, P., & Luu, T. T. (2024). Effect of supervisor incivility: Role of internal whistleblowing as a coping mechanism by hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 120, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M., Schümann, M., & Vincent-Höper, S. (2021). A conservation of resources view of the relationship between transformational leadership and emotional exhaustion: The role of extra effort and psychological detachment. Work & Stress, 35(3), 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, S. (2021). Role of workplace hazing in knowledge hiding and life satisfaction: Mediating role of moral disengagement and moderating role of psychological hardiness [Unpublished Master of Science Thesis, Capital University of Science and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan]. [Google Scholar]

- Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S. T., Bentley, T., & Nguyen, D. (2020). Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: A moderated, mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y. T., Sulistiawan, J., Ekowati, D., & Rizaldy, H. (2022). Work-family conflict and salespeople deviant behavior: The mediating role of job stress. Heliyon, 8(10), e10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul Haq, I., & Huo, C. (2024). The impacts of workplace bullying, emotional exhaustion, and psychological distress on poor job performance of healthcare workers in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration and Policy: An Asia-Pacific Journal, 27(1), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîrgă, D., Baciu, E. L., Lazăr, T. A., & Lupșa, D. (2020). Psychological capital protects social workers from burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Sustainability, 12(6), 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Information of the Respondents (n = 494) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 257 (52.02%) | Female | 237 (47.98%) |

| Education | |||

| Bachelor | Master | Doctoral degree | Others |

| 381 (77.13%) | 77 (15.58%) | 5 (1.01%) | 31 (6.28%) |

| Experience | |||

| Less than 3 years | 3–6 years | 7–10 years | Above 10 years |

| 46 (9.31%) | 168 (34.01%) | 251 (50.81%) | 29 (5.87%) |

| Position | |||

| Employees | 443 (89.68%) | Managers | 51 (10.32%) |

| Hotel Ranking | |||

| Four-star hotels | 257 (52.02%) | Five-star hotels | 237 (47.98%) |

| Variables | Item Codes | SFL | CA | CR | AVE | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace Hazing | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.656 | ||||

| WH1 | 0.791 | −1.645 | 2.812 | ||||

| WH2 | 0.772 | −1.593 | 2.771 | ||||

| WH3 | 0.794 | −1.491 | 1.751 | ||||

| WH4 | 0.756 | −1.080 | 2.508 | ||||

| WH5 | 0.846 | −1.732 | 2.375 | ||||

| WH6 | 0.841 | −1.721 | 2.215 | ||||

| WH7 | 0.826 | −1.836 | 2.265 | ||||

| WH8 | 0.774 | −1.733 | 2.939 | ||||

| WH9 | 0.819 | −1.733 | 2.759 | ||||

| WH10 | 0.847 | −1.953 | 2.314 | ||||

| WH11 | 0.806 | −1.495 | 2.336 | ||||

| WH12 | 0.826 | −1.693 | 2.100 | ||||

| WH13 | 0.843 | −1.308 | 2.921 | ||||

| WH14 | 0.774 | −1.854 | 2.398 | ||||

| WH15 | 0.823 | −1.433 | 2.335 | ||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | 0.838 | 0.841 | 0.638 | ||||

| EE1 | 0.745 | −1.009 | 2.404 | ||||

| EE2 | 0.793 | −1.062 | 2.828 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.855 | −1.363 | 2.228 | ||||

| Hope and Optimism | 0.935 | 0.937 | 0.711 | ||||

| HO1 | 0.837 | −1.677 | 1.945 | ||||

| HO2 | 0.855 | −1.517 | 2.241 | ||||

| HO3 | 0.837 | −1.675 | 2.349 | ||||

| HO4 | 0.824 | −1.715 | 2.622 | ||||

| HO5 | 0.862 | −1.627 | 2.763 | ||||

| HO6 | 0.824 | −1.462 | 2.669 | ||||

| Deviant Behavior | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.628 | ||||

| DB1 | 0.809 | −1.968 | 1.114 | ||||

| DB2 | 0.813 | −1.143 | 2.021 | ||||

| DB3 | 0.787 | −1.028 | 2.077 | ||||

| DB4 | 0.787 | −1.168 | 2.216 | ||||

| DB5 | 0.780 | −1.051 | 1.275 | ||||

| DB6 | 0.819 | −1.425 | 1.486 | ||||

| DB7 | 0.785 | −1.240 | 2.771 | ||||

| DB8 | 0.846 | −1.359 | 2.466 | ||||

| DB9 | 0.729 | −1.820 | 2.230 | ||||

| DB10 | 0.763 | −1.023 | 2.258 |

| Constructs | Mean | STD | Workplace Hazing | Emotional Exhaustion | Hope and Optimism | Deviant Behavior | Gen | Edu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace hazing | 4.031 | 0.938 | (0.810) | |||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 4.139 | 0.964 | 0.584 | (0.799) | ||||

| Hope and optimism | 4.150 | 0.942 | 0.629 | 0.553 | (0.843) | |||

| Deviant behavior | 4.134 | 0.929 | 0.462 | 0.451 | 0.606 | (0.792) | ||

| Gen | 1.358 | 0.480 | −0.007 | 0.005 | −0.013 | 0.044 | - | |

| Edu | 2.469 | 1.513 | −0.018 | −0.032 | −0.022 | −0.029 | −0.312 | - |

| Indices | Suggested Cut-Offs | Results |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <3 | 1347.001/496 = 2.716 |

| GFI | >0.8 | 0.860 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.060 |

| RFI | >0.9 | 0.907 |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.939 |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.917 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.946 |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.946 |

| Outcome Construct | Independent Variable | β | S. E | T | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Emotional exhaustion | Intercept | 0.811 | 0.118 | 6.906 | <0.001 | [0.580, 1.042] |

| Workplace hazing | 0.825 | 0.028 | 28.991 | <0.001 | [0.767, 0.880] | |

| R2 = 0.537 | ||||||

| Model 2: Deviant behavior | Intercept | 0.305 | 0.080 | 3.806 | <0.001 | [0.148, 0.463] |

| Workplace hazing | 0.500 | 0.031 | 16.248 | <0.001 | [0.440, 0.561] | |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.438 | 0.030 | 14.698 | <0.001 | [0.380, 0.497] | |

| R2 = 0.712 | ||||||

| The indirect effect of workplace hazing on deviant behavior via emotional exhaustion | ||||||

| Direct effect of X on Y | 0.500 | 0.031 | 16.248 | <0.001 | [0.440, 0.561] | |

| Bootstrap indirect effects | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |||

| Workplace hazing → Emotional exhaustion → Deviant behavior | 0.361 | 0.037 | 0.287 | 0.432 | ||

| β | S. E | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Predicting emotional exhaustion | |||||

| Intercept | 0.080 | 0.029 | 2.708 | 0.007 | [0.022, 0.137] |

| Gender | −0.017 | 0.054 | −0.206 | 0.837 | [−0.095, 0.117] |

| Education | 0.030 | 0.017 | 0.173 | 0.863 | [−0.031, 0.037] |

| Workplace hazing | 0.343 | 0.050 | 6.874 | 0.000 | [0.246, 0.443] |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.230 | 0.075 | 3.063 | 0.023 | [0.083, 0.378] |

| Workplace hazing × emotional exhaustion | 0.100 | 0.021 | 4.883 | 0.000 | [0.060, 0.141] |

| R2 = 0.715 | |||||

| The conditional direct effect of workplace hazing on emotional exhaustion at different levels of hope and optimism | |||||

| Hope and optimism (−1 SD) | 0.439 | 0.050 | 8.746 | 0.000 | [0.341, 0.538] |

| Hope and optimism (M) | 0.343 | 0.050 | 6.816 | 0.000 | [0.244, 0.442] |

| Hope and optimism (+1 SD) | 0.265 | 0.056 | 4.779 | 0.000 | [0.157, 0.376] |

| Model 2: Response variable model for predicting deviant behavior | |||||

| Constant | 4.153 | 0.063 | 65.690 | 0.000 | [4.029, 4.278] |

| Gender | −0.004 | 0.034 | −0.120 | 0.905 | [−0.072, 0.064] |

| Education | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.542 | 0.588 | [−0.016, 0.027] |

| Workplace hazing | 0.253 | 0.034 | 7.521 | 0.000 | [0.187, 0.320] |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.282 | 0.030 | 9.478 | 0.000 | [0.223, 0.340] |

| Hope and optimism | 0.265 | 0.049 | 5.445 | 0.000 | [0.169, 0.360] |

| Workplace hazing × hope and optimism | 0.108 | 0.034 | 3.202 | 0.001 | [0.042, 0.174] |

| Emotional exhaustion × hope and optimism | 0.054 | 0.033 | 1.674 | 0.095 | [−0.09, 0.118] |

| The conditional direct effect of workplace hazing on deviant behavior at different levels of hope and optimism | |||||

| Hope and optimism (−1 SD) | 0.356 | 0.046 | 7.796 | 0.000 | [0.267, 0.447] |

| Hope and optimism (M) | 0.253 | 0.034 | 7.521 | 0.000 | [0.187, 0.320] |

| Hope and optimism (+1 SD) | 0.171 | 0.043 | 3.951 | 0.001 | [0.086, 0.256] |

| The conditional indirect effect of X on Y: The conditional indirect effect of workplace hazing on deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion at different levels of hope and optimism | |||||

| Hope and optimism (−1 SD) | 0.101 | 0.025 | [0.055, 0.155] | ||

| Hope and optimism (M) | 0.097 | 0.024 | [0.55, 0.147] | ||

| Hope and optimism (+1 SD) | 0.086 | 0.026 | [0.040, 0.144] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljaier, O.; Alzubi, A.; Khadem, A.; Iyiola, K. Exploring the Impact of Workplace Hazing on Deviant Behavior in the Hospitality Sector: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Hope and Optimism. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020129

Aljaier O, Alzubi A, Khadem A, Iyiola K. Exploring the Impact of Workplace Hazing on Deviant Behavior in the Hospitality Sector: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Hope and Optimism. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020129

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljaier, Osama, Ahmad Alzubi, Amir Khadem, and Kolawole Iyiola. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Workplace Hazing on Deviant Behavior in the Hospitality Sector: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Hope and Optimism" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020129

APA StyleAljaier, O., Alzubi, A., Khadem, A., & Iyiola, K. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Workplace Hazing on Deviant Behavior in the Hospitality Sector: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Hope and Optimism. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020129