Fostering Playfulness in 2-to-6-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Study of Parental Play Support Profiles and Their Effects on Children’s Playfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Play Support

1.2. Change in Parental Play Support During Children’s Play

1.3. Effects of Parental Play Support on Children’s Playfulness

1.4. Parental Roles During Children’s Play

1.5. Summary and Research Questions

- Which profiles of parental play support can be identified?

- How does the profile affiliation of parental play support change over a two-year period?

- How do children’s age and gender and the presence of siblings affect the profile membership?

- Which parental play support profile fosters children’s playfulness?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

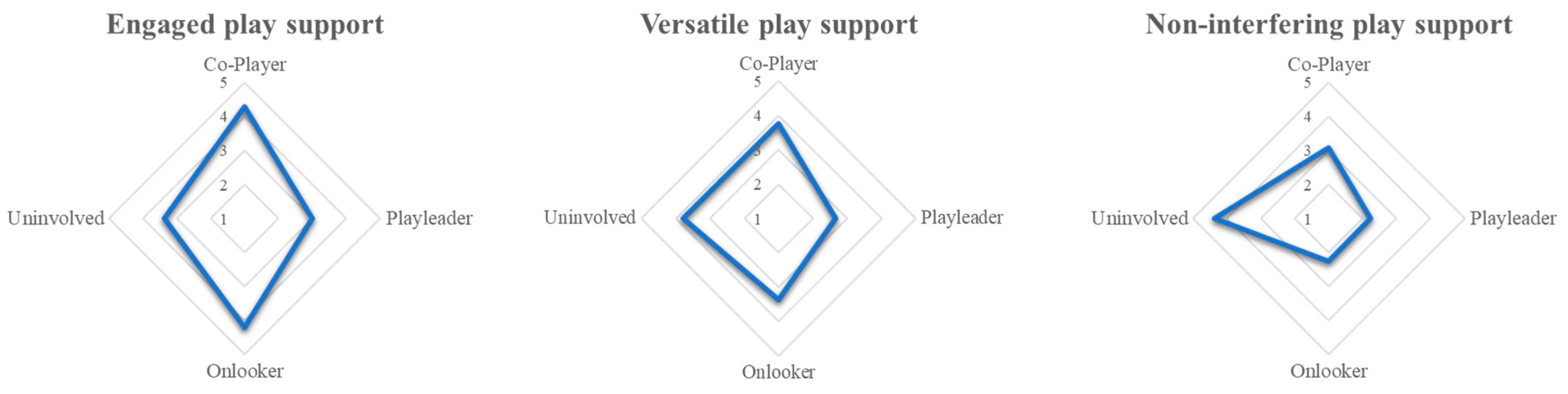

3.2. Profiles of Parental Play Support at T1 and T2

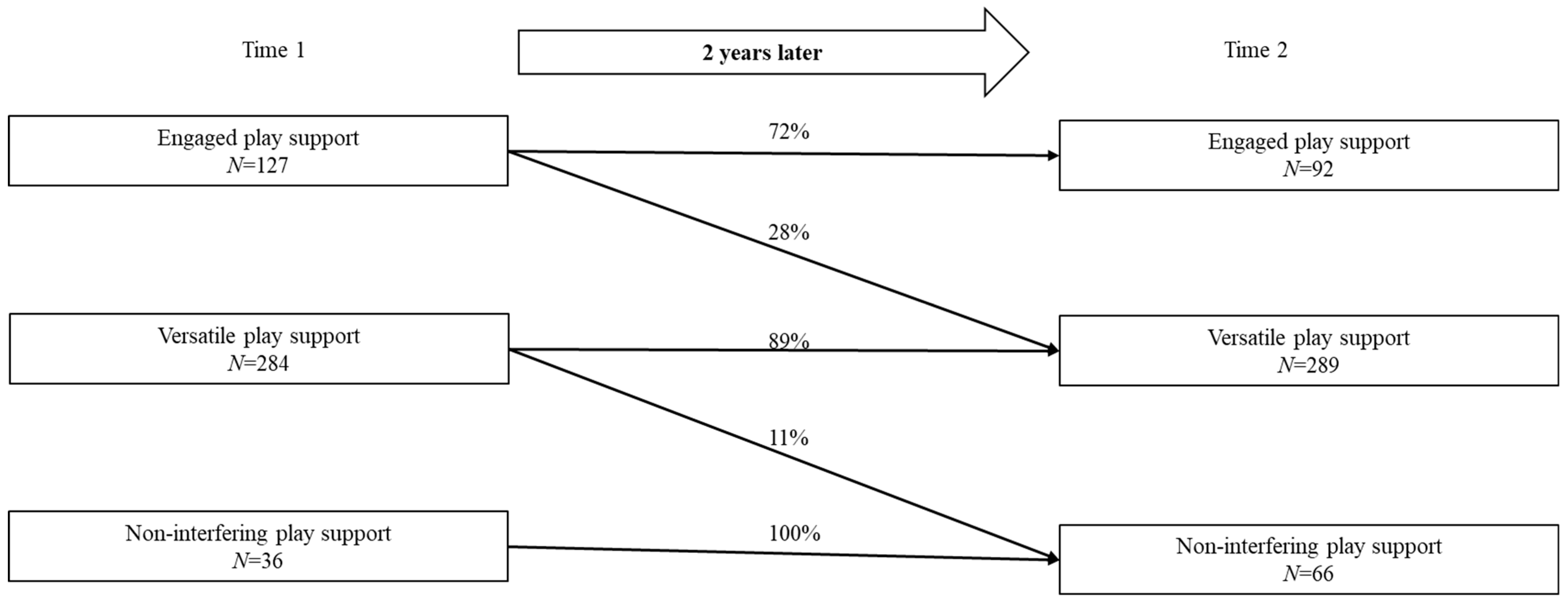

3.3. Changes in Play Support over 2 Years

3.4. Demographic Predictors of Profile Membership

3.5. Effects of Play Support Profiles on Children’s Playfulness

4. Discussion

4.1. Parental Play Support Profiles

4.2. Changes in the Play Support Profile Affiliation over Two Years

4.3. Association Between Age, Gender, and Siblings and Profile Membership

4.4. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Effects of Parental Play Support on Children’s Playfulness

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| German Version | English Version | |

|---|---|---|

| Co-Player | ||

| 1. | Wenn mein Kind möchte, dass ich mitspiele, passe ich mich seinem Spielfluss an und überlasse ihm die Führung des Spiels. | When my child invites me to play with him/her, I go with his/her flow and let him/her direct the play. |

| 2. | Wenn mein Kind möchte, dass ich mitspiele, beteilige ich mich als gleichberechtigte/r Spielpartner/in (indem ich mich ohne Absichten auf sein Spiel einlasse). | When my child invites me to play with him/her, I participate as an equal (by joining in his/her play without pursuing objectives). |

| 3. | Wenn mein Kind möchte, dass ich mitspiele, lasse ich mich auf seine Spielideen ein (z.B. indem ich mich zu ihm auf den Boden setze oder Rollen übernehme, die es mir zuteilt). | When my child invites me to play with him/her, I go along with his/her play ideas (for example, by sitting down on the floor with him/her or playing a role that he/she gives me). |

| Playleader | ||

| 4. | Wenn mein Kind nicht ins Spiel findet, unterstütze ich es mit Spielvorschlägen. | If my child does not engage in play, I encourage him/her by making play suggestions. |

| 5. | Wenn ich merke, dass sich das Spiel meines Kindes erschöpft, schlage ich ihm andere Spielmöglichkeiten vor. | When my child loses interest in what he/she is playing, I suggest other things to play. |

| 6. | Wenn ich merke, dass das Spiel meines Kindes ins Stocken gerät, gebe ich ihm Hinweise, wie es sein Spiel erweitern kann. | When I notice my child’s play is about to wind down, I give suggestions on how he/she can extend his/her play. |

| Onlooker | ||

| 7. | Ich schaue meinem Kind während seines Spiels aufmerksam zu. | I watch my child with attention when he/she plays. |

| 8. | Ich beobachte das Spiel meines Kindes, um Erkenntnisse über seine aktuellen Themen und Interessen zu gewinnen. | I observe my child’s play to learn about his/her current interests and favorite topics. |

| 9. | Ich bin während des Spiels präsent und in der Nähe meines Kindes. | While my child is playing, I am present and nearby. |

| Uninvolved | ||

| 10. | Während mein Kind spielt, erledige ich organisatorische, administrative Aufgaben (z.B. Telefonate, Einkaufslisten, Papierkram). | When my child plays, I do organizational, administrative tasks (such as make telephone calls, make grocery list, do paperwork). |

| 11. | Während mein Kind spielt, erledige ich Haushaltstätigkeiten (z.B. Putzen, Waschen, Gartenarbeit). | While my child is playing, I do housework (such as cleaning, laundry, work in garden). |

| 12. | Während mein Kind spielt, bereite ich Mahlzeiten zu. | While my child is playing, I cook meals. |

Appendix B

| χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ∆χ2 | ∆df | p | ∆CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | 290.393 | 212 | 0.000 | 0.980 | 0.024 | 0.041 | ||||

| Metric | 296.486 | 220 | 0.000 | 0.980 | 0.023 | 0.042 | 6.505 | 8 | 0.591 | 0.000 |

| Scalar | 359.545 | 228 | 0.000 | 0.966 | 0.030 | 0.045 | 64.826 | 8 | 0.000 | −0.014 |

| Partial scalar | 301.099 | 224 | 0.000 | 0.980 | 0.023 | 0.042 | 4.522 | 4 | 0.340 | 0.000 |

Appendix C

| Playfulness T1 β (SE) | Playfulness T2 β (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.81 (0.07) *** | 1.96 (0.15) *** |

| Playfulness T1 | - | 0.60 (0.04) *** |

| Non-interfering play support | −0.23 (0.08) ** | −0.07 (0.06) |

| Versatile play support | −0.14 (0.04) ** | −0.07 (0.03) † |

| Age (in months) | 0.01 (0.00) *** | −0.00 (0.00) *** |

| Gender | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.40 |

| Playfulness T1 β (SE) | Playfulness T2 β (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.99 (0.11) *** | 3.13 (0.21) *** |

| Playfulness T1 | - | 0.27 (0.06) *** |

| Non-interfering play support | 0.12 (0.11) | −0.15 (0.13) |

| Versatile play support | 0.03 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Age (in months) | 0.01 (0.00) *** | −0.01 (0.00) ** |

| Gender | 0.07 (0.06) | 0.00 (0.07) |

| R2 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| 1 | When children’s playfulness was assessed solely through parent ratings, the cross-sectional associations with parental play support profiles were significant, whereas no significant associations were found when using only teacher ratings (see Appendix C for full results). |

References

- Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L. (1991). The playful child: Measurement of a disposition to play. Play and Culture, 4(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(Pt 2), 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, G., & Dias, G. (2017). The importance of outdoor play for young children’s healthy development. Porto Biomedical Journal, 2(5), 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, S. A., Stagnitti, K., Taket, A., & Nolan, A. (2012). Early peer play interactions of resilient children living in disadvantaged communities. International Journal of Play, 1(3), 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeux, G., & Soromenho, G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. H., Tein, J.-Y., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., & Lemery-Chalfant, K. (2025). Predictors of stability/change in observed parenting patterns across early childhood: A latent transition approach. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 70, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. L., & Muthén, B. (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Duss, I., Ruedisueli, C., Wustmann Seiler, C., & Lannen, P. (2024). Development of playfulness in children with low executive functions: The role of parental playfulness and parental playtime with their child. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duss, I., Rüdisüli, C., Wustmann Seiler, C., & Lannen, P. (2023). Playfulness from children’s perspectives: Development and validation of the Children’s Playfulness Scale as a self-report instrument for children from 3 years of age. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1287274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M., Gollwitzer, M., & Schmitt, M. (2017). Statistik und Forschungsmethoden [Statistics and research methods] (5th ed.). Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Elkind, D. (2010). Play. In V. Washington, & J. D. Andrews (Eds.), Children of 2020: Creating a better tomorrow (pp. 85–89). The Council for Professional Recognition. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., & Reifel, R. S. (2005). Play and child development (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, W. K., & Chung, K. K. H. (2022). Parental play supportiveness and kindergartners’ peer problems: Children’s playfulness as a potential mediator. Social Development, 31(4), 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, W. K., & Chung, K. K. H. (2025). Interrelationships among parental play support and kindergarten children’s playfulness and creative thinking processes. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 58, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmitrová, V., & Gmitrov, J. (2003). The impact of teacher-directed and child-directed pretend play on cognitive competence in kindergarten children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 30(4), 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Fremmer-Bombik, E., Kindler, H., Scheuerer-Englisch, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child–father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Social Development, 11(3), 301–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J. R., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods, 11, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.-P., & Lamb, M. E. (1997). Father involvement in Sweden: A longitudinal study of its stability and correlates. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21(3), 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivrendi, A. (2020). Early childhood teachers’ roles in free play. Early Years, 40(3), 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H., Pyle, A., Alaca, B., & Fesseha, E. (2021). Playing with a goal in mind: Exploring the enactment of guided play in Canadian and South African early years classrooms. Early Years, 41(5), 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A., Halliburton, A., & Humphrey, J. (2013). Child–mother and child–father play interaction patterns with preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. a. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, S., & Yurt, Ö. (2017). An investigation of playfulness of pre-school children in Turkey. Early Child Development and Care, 187(8), 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaForett, D. R., & Mendez, J. L. (2017). Children’s engagement in play at home: A parent’s role in supporting play opportunities during early childhood. Early Child Development and Care, 187, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N. K., Ang, T. F., Por, L. Y., & Liew, C. S. (2018). The impact of play on child development—A literature review. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(5), 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, S. T., & Cooper, B. R. (2016). Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Development Perspectives, 10(1), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C., & Bi, X. (2025). Paternal involvement and peer competence in young children: The mediating role of playfulness. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1477432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J. N. (1977). Playfulness. Its relationship to imagination and creativity. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard, A. S., Lerner, M. D., Hopkins, E. J., Dore, R. A., Smith, E. D., & Palmquist, C. M. (2013). The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., & Qiu, Y. (2024). Parent-child relationship and social competence in Chinese preschoolers: A latent class analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 163, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, K., Howard, J., Miles, G., & Crowley, K. (2011). Differences in practitioners’ understanding of play and how this influences pedagogy and children’s perceptions of play. Early Years, 31(2), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M. A. (2016). Supporting child play. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(2), 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Muhonen, H., von Suchodoletz, A., Doering, E., & Kärtner, J. (2019). Facilitators, teachers, observers, and play partners: Exploring how mothers describe their role in play activities across three communities. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus plus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, E., Wustmann Seiler, C., Perren, S., & Simoni, H. (2015). Young children’s self-perceived ability: Development, factor structure and initial validation of a self-report instrument for preschoolers. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P., Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (2008). Teacher or playmate? Asian immigrant and Euro-American parents’ participation in their young children’s daily activities. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 36(2), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L. (2017). Socially desirable responding on self-reports. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1–5). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S., Sticca, F., Weiss-Hanselmann, B., & Burkhardt Bossi, C. (2019). Let us play together! Can play tutoring stimulate children’s social pretend play level? Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17(3), 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada-Mateus, M., Obando, D., Sandoval-Reyes, J., Mejia-Lozano, M. A., & Hill, J. (2024). The role of parental involvement in the development of prosocial behavior in young children: An evolutionary model among Colombian families. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Rentzou, K. (2013). Greek preschool children’s playful behaviour: Assessment and correlation with personal and family characteristics. Early Child Development and Care, 183(11), 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. L., StGeorge, J., & Freeman, E. E. (2021). A systematic review of father-child play interactions and the impacts on child development. Children, 8(21), 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A., & Saebel, J. (1997). Individual differences in parent-child play styles: Their nature and possible consequences. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED406010 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Rüdisüli, C., Duss, I., Lannen, P., & Wustmann Seiler, C. (2023). External assessment of teachers’ roles during children’s free play and its relation to types of children’s play. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1287273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J., Brown, T., & Yu, M.-L. (2022). The association between school-aged children’s self-reported levels of playfulness and quality of life: A pilot investigation. International Journal of Play, 11(3), 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M., Falkenberg, I., & Berger, P. (2022). Parent-child play and the emergence of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in childhood: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 822394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrard, A., & Tan, C. C. (2024). Children’s eating behavior and weight-related outcomes: A latent profile analysis of parenting style and coparenting. Eating Behaviors, 52, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E., Nederend, M., Penninx, L., Tajik, M., & Boom, J. (2014). The teacher’s role in supporting young children’s level of play engagement. Early Child Development and Care, 184(8), 1233–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skard, G., & Bundy, A. C. (2011). Test of playfulness (ToP)—Test zur Spielfähigkeit. Deutsche Übersetzung: Barbara und Jürgen Dehnhardt. Schulz-Kirchner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Skene, K., O’Farrelly, C. M., Byrne, E. M., Kirby, N., Stevens, E. C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2022). Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Development, 93(4), 1162–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgess, J., Rodger, S., & Ozanne, A. (2002). A review of the use of self-report assessment with young children. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(3), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y., Okada, K., Hoshino, T., & Anme, T. (2015). Developmental trajectories of social skills during early childhood and links to parenting practices in a Japanese sample. PLoS ONE, 10(8), e0135357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Shannon, J. D., Cabrera, N. J., & Lamb, M. E. (2004). Fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Development, 75(6), 1806–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandler, N., & Proyer, R. T. (2022). Deriving information on play and playfulness of 3-5-year-olds from short written descriptions: Analyzing the frequency of usage of indicators of playfulness and their associations with maternal playfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trawick-Smith, J., & Dziurgot, T. (2011). “Good-fit” teacher-child play interactions and the subsequent autonomous play of preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(1), 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, G., Neto, C., & Rieffe, C. (2016). Preschoolers’ free play—Connections with emotional and social functioning. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 8(1), 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman-Levi, A. (2021). Differences in how mothers and fathers support children playfulness. Infant and Child Development, 30(5), e2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warash, B. G., Root, A. E., & Devito Doris, M. (2017). Parents’ perceptions of play: A comparative study of spousal perspectives. Early Child Development and Care, 187(5–6), 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemariam, K. T. (2014). Cautionary tales on interrupting children’s play: A study from Sweden. Childhood Education, 90(4), 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D., Neale, D., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Solis, S. L., Hopkins, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Zosh, J. M. (2017). The role of play in children’s development: A review of the evidence. The LEGO Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wustmann Seiler, C., Duss, I., Rüdisüli, C., & Lannen, P. (2024). Developmental trajectories of children’s playfulness in two- to six-year-olds: Stable, growing, or declining? Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2, 1426985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wustmann Seiler, C., Lannen, P., Duss, I., & Sticca, F. (2021). Mitspielen, (An)Leiten, Unbeteiligt sein? Zusammenhänge kindlicher und elterlicher Playfulness: Eine Pilotstudie [Playing along, leading, being uninvolved? Parental play guidance and children’s playfulness: A pilot study]. Frühe Bildung, 10(3), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wustmann Seiler, C., Rüdisüli, C., & von Felten, R. (2023). Was braucht ihr für euer Spiel—Darf ich mitspielen? Selbstwahrgenommene Spielbegleitung von Lehrpersonen in Schweizer Kindergärten [What do you need for your play—May I join? Teachers’ self-perceived play participation in Swiss kindergartens]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 70(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youell, B. (2008). The importance of play and playfulness. Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, 10(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. V., & Gibson, J. L. (2023). Evidence for protective effects of peer play in the early years: Better peer play ability at age 3 Years predicts lower risks of externalising and internalising problems at age 7 years in a longitudinal cohort analysis. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(6), 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zosh, J. M., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Solis, S. L., & Whitebread, D. (2017). Learning through play: A review of the evidence. The LEGO Foundation. [Google Scholar]

| N = 447 | |

|---|---|

| Children’s gender (female/male) | 208/239 |

| Children’s age in months (SD) | 58.2 (16.9) |

| Number of siblings | |

| No siblings | 86 (18.3%) |

| One sibling | 262 (55.9%) |

| Two or more siblings | 99 (21.1%) |

| Educational setting of the child | |

| Childcare center | 197 (44%) |

| Kindergarten | 250 (56%) |

| Nationality | |

| Swiss | 400 (89%) |

| Other | 47 (11%) |

| Family language | |

| German or Swiss-German | 422 (94%) |

| Other | 25 (6%) |

| Mothers highest Education (N = 401) | |

| Vocational education | 138 (34%) |

| Academic | 247 (62%) |

| Missing | 16 (4%) |

| Fathers highest Education (N = 46) | |

| Vocational education | 11 (24%) |

| Academic | 35 (76%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) |

| N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co-Player T1 | 447 | 3.83 | 0.74 | - | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Playleader T1 | 447 | 2.70 | 0.73 | 0.04 | - | |||||||||||

| 3 | Onlooker T1 | 447 | 3.48 | 0.63 | 0.32 *** | 0.22 *** | - | ||||||||||

| 4 | Uninvolved T1 | 447 | 3.73 | 0.71 | −0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.26 *** | - | |||||||||

| 5 | Co-Player T2 | 447 | 3.51 | 0.79 | 0.59 *** | 0.03 | 0.27 *** | −0.19 *** | - | ||||||||

| 6 | Playleader T2 | 447 | 2.78 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.51 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.16 *** | 0.16 *** | - | |||||||

| 7 | Onlooker T2 | 447 | 3.27 | 0.64 | 0.29 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.57 *** | −0.20 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.34 *** | - | ||||||

| 8 | Uninvolved T2 | 447 | 3.84 | 0.66 | −0.14 ** | −0.12 * | −0.17 *** | 0.54 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.21 *** | - | |||||

| 9 | Age (in months) | 447 | 58.18 | 16.86 | −0.23 *** | −0.16 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.17 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.17 *** | 0.16 *** | - | ||||

| 10 | Gender (female) | 447 | 0.46 | - | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −09 | −0.04 | - | |||

| 11 | Children’s playfulness T1 | 446 | 3.92 | 0.41 | −0.04 | −0.14 ** | −0.00 | 0.11 * | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.09 * | 0.32 *** | 0.04 | - | ||

| 12 | Children’s playfulness T2 | 446 | 4.00 | 0.39 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.12 ** | −0.01 | 0.14 ** | 0.04 | 0.21 *** | 0.02 | −0.09 * | 0.02 | 0.44 *** | - | |

| 13 | Siblings (yes) | 443 | 0.84 | - | −0.17 *** | −0.08 | −0.20 *** | 0.13 ** | −0.17 *** | −0.15 ** | −0.10 * | 0.19 *** | 0.22 *** | −0.05 | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | - |

| 14 | Parental age | 446 | 39.11 | 4.53 | −0.14 ** | −0.06 | −0.10 * | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.12 * | −0.11 * | −0.09 | 0.22 *** | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| AIC | BIC | SABIC | Entropy | ALMR LR Test p-Value | Classification Accuracy | Group Size | BLRT p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | ||||||||

| 1-Profile | 3818.58 | 3851.40 | 3826.01 | - | - | - | 100% | - |

| 2-Profiles | 3756.28 | 3809.61 | 3768.35 | 0.393 | p = 0.359 | 0.792–0.802 | 51.2–48.6% | p = 0.000 |

| 3-Profiles | 3708.50 | 3782.35 | 3725.22 | 0.748 | p = 0.004 | 0.846–0.901 | 6.2–71.4% | p = 0.000 |

| 4-Profiles | 3696.44 | 3790.80 | 3717.81 | 0.810 | p = 0.094 | 0.856–0.902 | 1.6–70.9% | p = 0.000 |

| 5-Profiles | 3680.60 | 3795.47 | 3706.61 | 0.844 | p = 0.000 | 0.838–0.999 | 0.4–68.7% | p = 0.000 |

| 6-Profiles | 3671.56 | 3806.95 | 3702.22 | 0.855 | p = 0.068 | 0.838–0.999 | 0.1–68.5% | p = 0.040 |

| T2 | ||||||||

| 1-Profile | 3750.23 | 3783.05 | 3757.66 | - | - | - | 100% | - |

| 2-Profiles | 3637.89 | 3691.22 | 3649.97 | 0.539 | p = 0.000 | 0.832–0.875 | 36.2–63.8% | p = 0.000 |

| 3-Profiles | 3616.31 | 3690.16 | 3633.03 | 0.692 | p = 0.061 | 0.821–0.866 | 4.4–60.2% | p = 0.000 |

| 4-Profiles | 3581.19 | 3675.55 | 3602.56 | 0.780 | p = 0.294 | 0.792–0.893 | 3.6–47.7% | p = 0.000 |

| 5-Profiles | 3570.04 | 3684.91 | 3596.05 | 0.809 | p = 0.124 | 0.797–0.904 | 1.8–47.7% | p = 0.000 |

| 6-Profiles | 3564.22 | 3699.60 | 3594.87 | 0.814 | p = 0.279 | 0.768–0.969 | 0.1–47.4% | p = 0.088 |

| Profile Affiliation | F-Ratio | Sig. Level | Games–Howell Post Hoc Test (Difference in Mean) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaged Play Support M (SD) | Versatile Play Support M (SD) | Non-Interfering Play Support M (SD) | 1 and 2 | 1 and 3 | 2 and 3 | |||

| Co-Player T1 | 4.31 (0.56) | 3.70 (0.66) | 3.15 (0.94) | 57.3 | <0.001 | −0.61 *** | −1.15 *** | −0.55 ** |

| Playleader T1 | 3.00 (0.76) | 2.61 (0.67) | 2.34 (0.68) | 16.9 | <0.001 | −0.39 *** | −0.66 *** | −0.27 |

| Onlooker T1 | 4.17 (0.37) | 3.33 (0.36) | 2.28 (0.38) | 430.7 | <0.001 | −0.84 *** | −1.89 *** | −1.05 *** |

| Uninvolved T1 | 3.39 (0.75) | 3.80 (0.63) | 4.39 (0.56) | 39.0 | <0.001 | 0.42 *** | 1.00 *** | 0.59 *** |

| χ2 | df | p | Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (Difference in W) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2 | 1 and 3 | 2 and 3 | ||||

| Children’s age | 31.752 | 2 | <0.001 | 7.12 *** | 5.82 *** | 2.51 |

| Parental age | 3.550 | 2 | 0.170 | - | - | - |

| Gender | 0.197 | 2 | 0.908 | - | - | - |

| Presence of siblings | 40.441 | 2 | <0.001 | 8.17 *** | 5.21 *** | 2.06 |

| Playfulness T1 β (SE) | Playfulness T2 β (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.46 (0.07) *** | 2.42 (0.16) *** |

| Playfulness T1 | - | 0.50 (0.04) *** |

| Non-interfering play support | −0.09 (0.08) | −0.13 (0.07) * |

| Versatile play support | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) † |

| Age (in months) | 0.01 (0.00) *** | −0.01 (0.00) *** |

| Gender | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duss, I.; Rüdisüli, C.; Wustmann Seiler, C.; Lannen, P. Fostering Playfulness in 2-to-6-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Study of Parental Play Support Profiles and Their Effects on Children’s Playfulness. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121716

Duss I, Rüdisüli C, Wustmann Seiler C, Lannen P. Fostering Playfulness in 2-to-6-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Study of Parental Play Support Profiles and Their Effects on Children’s Playfulness. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121716

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuss, Isabelle, Cornelia Rüdisüli, Corina Wustmann Seiler, and Patricia Lannen. 2025. "Fostering Playfulness in 2-to-6-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Study of Parental Play Support Profiles and Their Effects on Children’s Playfulness" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121716

APA StyleDuss, I., Rüdisüli, C., Wustmann Seiler, C., & Lannen, P. (2025). Fostering Playfulness in 2-to-6-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Study of Parental Play Support Profiles and Their Effects on Children’s Playfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121716