The Relationship Between Career Adaptability and Work Engagement Among Young Chinese Workers: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Moderating Effects of Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy and Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Conceptual Framework

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- How does career adaptability influence work engagement through job satisfaction in an AI-driven environment?

- What are the moderating roles of AI self-efficacy and AI anxiety in this process?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Career Adaptability (CA)

2.2.2. Job Satisfaction (JS)

EFA for JS

CFA for JS

2.2.3. Self-Efficacy in AI Use (SEAI)

EFA for SEAI

CFA for SEAI

2.2.4. AI Anxiety (AIA)

EFA for AIA

CFA for AIA

2.2.5. Work Engagement (WE)

EFA for WE

CFA for WE

Reliability Analysis of the Scales

2.3. Statistical Methods and Data Analysis Tools

2.3.1. EFA and CFA Procedures

2.3.2. Measurement Model Estimation and Validation Procedures

- Stage 1: Latent Variable Mediation (AMOS)

- Stage 2: Moderated Mediation Analysis (PROCESS)

- (1)

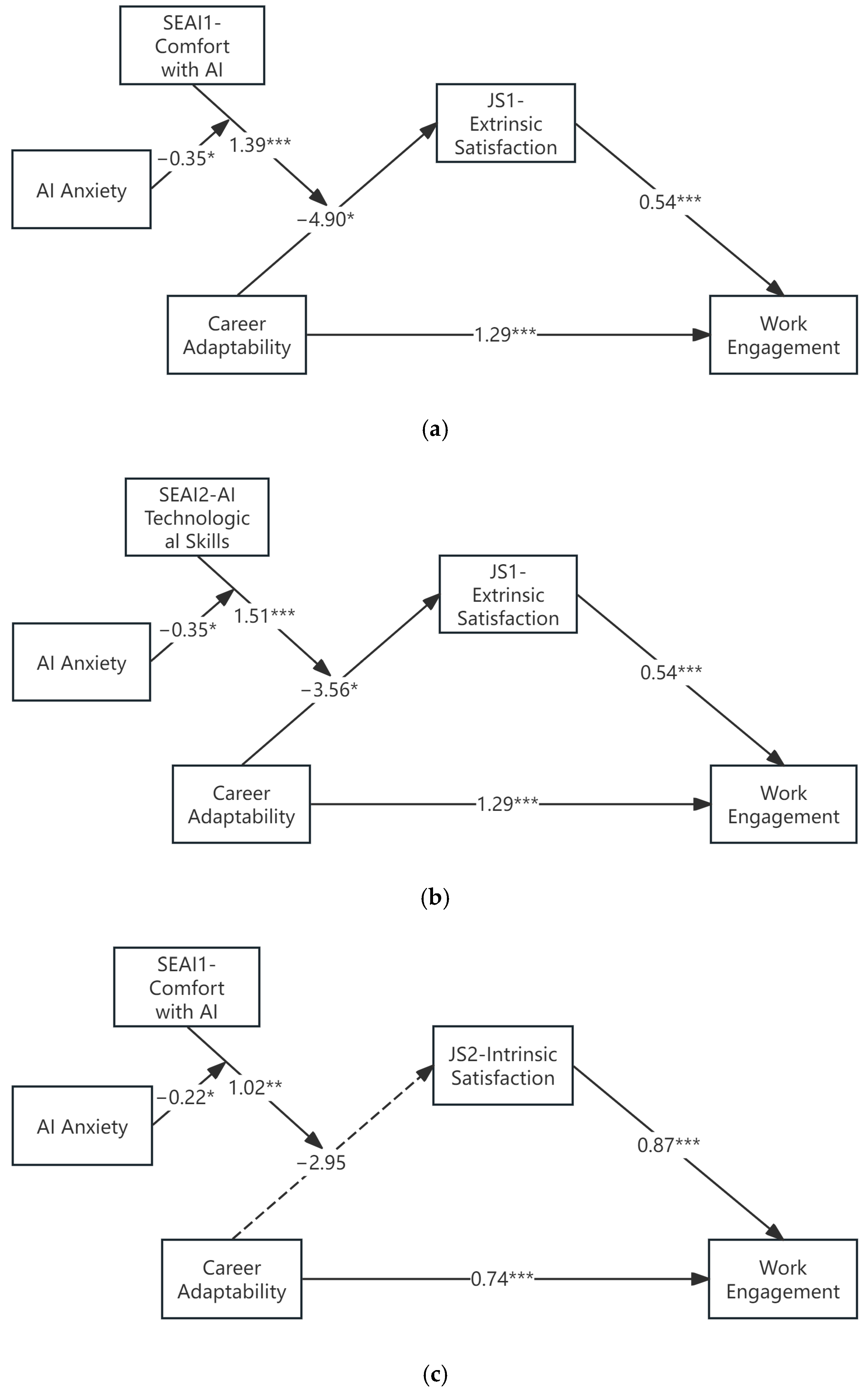

- Pathway 1 (Extrinsic Focus, SEAI1): The indirect effect of CA (Total Score) on Work Engagement through Extrinsic Satisfaction (JS1), jointly moderated by SEAI1 and AIA.

- (2)

- Pathway 2 (Second SEAI Dimension): The indirect effect of CA (Total Score) on Work Engagement through Extrinsic Satisfaction (JS1), jointly moderated by SEAI2 and AIA.

- (3)

- Pathway 3 (Intrinsic Focus, SEAI1): The indirect effect of CA (Total Score) on Work Engagement through Intrinsic Satisfaction (JS2), jointly moderated by SEAI1 and AIA. Standardized effect sizes (ΔR2 for interaction terms) were reported for significant interaction effects, and simple slopes/interactions were graphed. Age, ethnicity, marriage, education, income, and industry were included as control variables in all hypothesis testing models.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model Validation

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

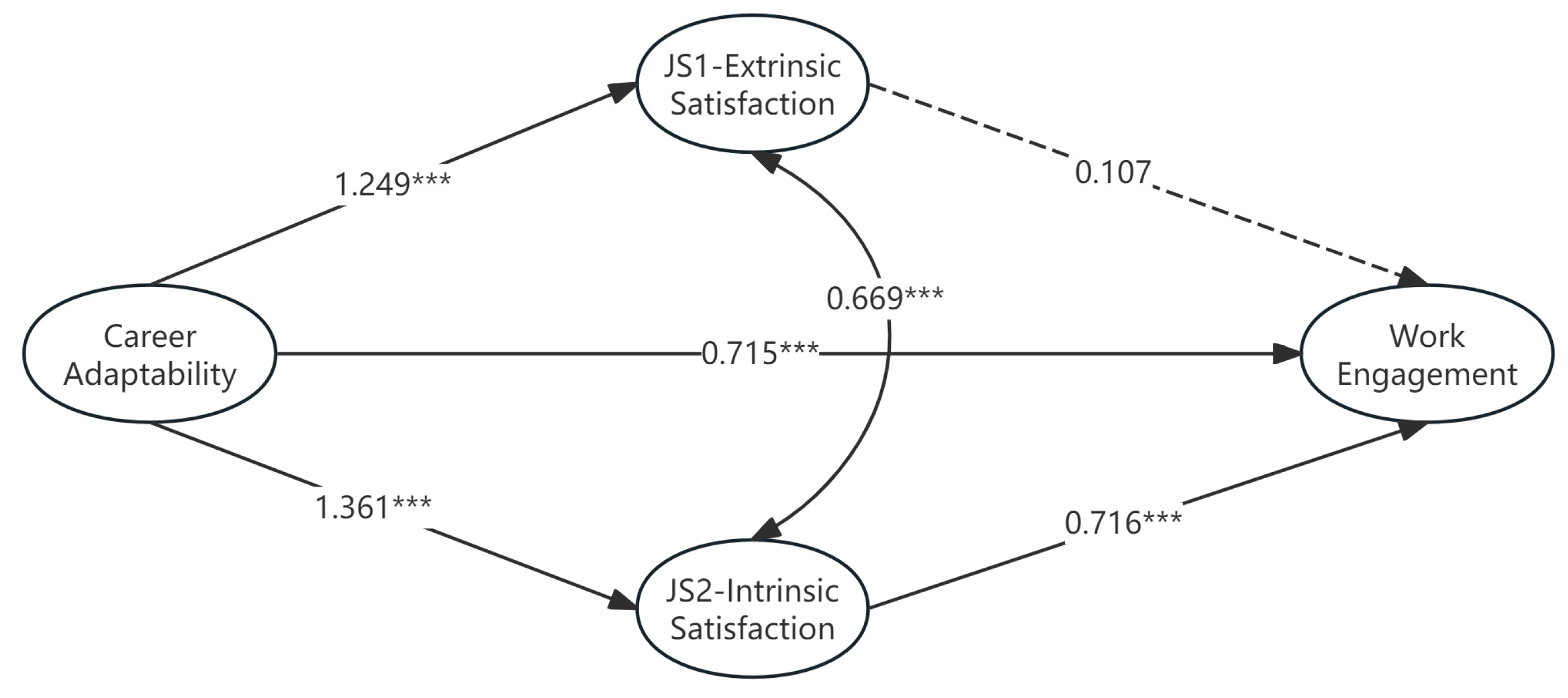

3.3. Latent Variable Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis for Mediation Paths

3.3.1. Model Specification and Estimation

3.3.2. Model Fit

3.3.3. Hypothesis Testing: Mediation Effects in the Latent Model

4. Discussion

- The Centrality of Intrinsic Satisfaction (JS2) as the Key Mediator

- When ‘Technical Confidence’ Meets ‘Existential Angst’: AI Anxiety Dampens, but Does Not Nullify, the Benefits of AI Self-Efficacy

- Measurement Reflections—Validating Complex Constructs

4.1. Theoretical Contributions: Extending Theories of Adaptation, Motivation and Cognitive-Affective Interaction in the AI Domain

- (1)

- Expanding COR Theory Application in AI Transformation by Emphasizing the Centrality of “Intrinsic Returns”: Adding to the extant literature that has only established adaptability as a resource (Rudolph et al., 2017), our empirical study extends it through SEM, demonstrating that intrinsic job satisfaction (JS2) is the core mechanism for transforming career adaptability (CA) into work engagement (WE). This study offers a focused psychologically based empirical model for the COR (Conservation of Resources) theory’s cycle of investment and gain in resources (Hobfoll, 2011) in technology—highlighting how intrinsic work quality is pivotal to forming spirals of conservation and gain. It therefore operates as a qualifier, or modifier, to views that overstate the importance of extrinsic motivation.

- (2)

- Implications and Directions for Future SCT-Based Research on Cognitive-Affective Complexity in AI Adaptation: Although the proposed interaction effects were not upheld, the early pattern of results from PROCESS add to our understanding within Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) regarding person–behavior–environment interactions (especially in the AI context) (Bandura, 1997; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This result warns against univariate additive models, where the positive influence of SEAI (Kim & Lee, 2024) and the negative impact of AIA (Tian & Oviatt, 2021) are assumed to directly add. It instead suggests the possibility of multiple non-linear relationships between cognitive beliefs (SEAI) and affective responses (AIA) for AI adoption. The preliminary findings and methodological reflections presented here strongly encourage future work using more refined (e.g., Latent Variable Modeling) methods to better understand the mechanisms of SCT in the new AI adaptation domain.

- (3)

- Reinforcing the Importance of Measurement Precision and Methodological Competency in AI Research. Given the discrepancy between the PROCESS and SEM results, as well as contrasting mediating roles of extrinsic job satisfaction (vs. intrinsic job satisfaction), the empirical investigation proves that construct dimensionality should be dealt with, allowing low-level measurement error to be reduced when researching the consequences of AI effects. Composite scores alone mask important mechanisms and may even result in false conclusions based on statistical artifacts. This study serves as a reminder that AI research in relation to employee psychology should pursue more elaborate theoretical models (per the multistage model, at least) and careful measurement choices, methodological reflexivity (e.g., what methods are suited for PROCESS exploration vs. SEM confirmation), and an unwavering aim for improved construct validity.

4.2. Practical Relevance: From Training Skills to Human-Centered AI Management

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- (1)

- Innate Limitation for Causal Inference—Cross-Sectional Design: This is the most significant limitation, as the cross-sectional design prevents us from confirming the directionality or causality implied by our mediation model. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs (e.g., multi-wave panel studies) to track these relationships over time and test the proposed causal chain. Additionally, experimental or quasi-experimental designs (e.g., comparing employee transitions before and after AI implementation in organizations with different support structures) would provide stronger causal evidence.

- (2)

- Sample and Contextual Limitations: The sample in this study is limited to young Chinese employees (aged 18–25), which restricts the generalizability of the findings to a broader population, such as older workers or individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, the impact of AI is not uniformly distributed across organizations. Replication of these findings in more diverse samples and contexts is necessary, with explicit testing of the moderating roles of important contextual variables (e.g., AI ethical, leadership style, job autonomy).

- (3)

- Common Method Bias (CMB): The reliance on self-report data can inflate relationships. Although procedural checks and Harman’s test were employed and did not indicate a clear dominance of a single factor, this test has limited diagnostic value (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Future research should incorporate multi-source data (e.g., supervisor ratings) or multiple methods (e.g., behavioral indicators, system-logged data) to better address CMB concerns. Additionally, time-lagged designs should be considered to mitigate these biases.

- (4)

- The Validation of Complex Constructs and Model Specification: Validating complex psychological constructs, especially adapted or foreign scales, presents inherent challenges. The lack of sufficient participants also limited our ability to perform split-half cross-validation for all scales (Leong & Ott-Holland, 2014). Moreover, the failure to fit an appropriate latent model for Overall Job Satisfaction (JS_All) in AMOS experimentation impeded our ability to test more complex models, particularly those involving JS enrollment in SEM. This issue highlights the importance of distinguishing between JS facets and suggests structural concerns within the JS_All construct. Although the overall SEM fit was acceptable, the significant Bollen–Stine bootstrap p-value indicates potential model misfit, which should be considered when interpreting the coefficients.

- (5)

- The “Differences in Interactions”—Inconsistent Evidence from PROCESS and SEM: This limitation warrants serious attention. PROCESS analysis consistently found significant three-way interactions. However, more rigorous SEM analysis showed that several key foundational pathways upon which these interactions depend were not significant. This discrepancy suggests that the findings in PROCESS may have been exaggerated by measurement error. This emphasizes the need for future research to employ Latent Moderated Structural Equations (LMS), which is considered the gold standard for testing moderation—especially when latent interactions are included—to obtain more reliable results.

- (6)

- The “Tip of the Iceberg”—Model Parsimony and Omitted Variables: Our model focused on a specific set of variables, leaving out potentially important factors. Future studies should aim to develop more comprehensive theoretical models that include additional individual-level variables (e.g., learning agility, personality), task-level factors (e.g., AI complexity, human-AI interaction quality), or organizational influences (e.g., transformational leadership, organizational justice, training effectiveness).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIA | AI Anxiety |

| B-S p | Bollen–Stine bootstrap p-value |

| CA | Career Adaptability |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CMB | Common Method Bias |

| COR | Conservation of Resources theory |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| JS | Job Satisfaction |

| JS1 | Extrinsic Job Satisfaction |

| JS2 | Intrinsic Job Satisfaction |

| LMS | Latent Moderated Structural equations |

| M | Mediator variable |

| PROCESS | PROCESS macro (Hayes) |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| SEAI | AI Self-Efficacy |

| SEAI1 | Comfort with AI |

| SEAI2 | AI Technological Skills |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| W | Primary moderator variable |

| WE | Work Engagement |

| X | Independent variable |

| Y | Dependent variable |

| Z | Second-stage moderator variable |

Appendix A

| Factor (Theoretical Name) and Item | CFA Std. Loading |

|---|---|

| Factor 1: Control (3 items) | |

| SQ10_1 (“Making decisions by myself.”) | 0.506 |

| SQ10_4 (“Sticking up for my beliefs.”) | 0.486 |

| SQ10_6 (“Doing what’s right for me.”) | 0.791 |

| Factor 2: Concern (5 items) | |

| SQ11_2 (“Thinking about what my future will be like.”) | 0.603 |

| SQ11_3 (“Preparing for the future.”) | 0.687 |

| SQ11_4 (“Becoming aware of the educational and career choices that I must make.”) | 0.481 |

| SQ11_5 (“Planning how to achieve my goals.”) | 0.723 |

| SQ11_6 (“Concerned about my career.”) | 0.662 |

| Factor 3: Curiosity (6 items) | |

| SQ12_1 (“Looking for opportunities to grow as a person.”) | 0.641 |

| SQ12_2 (“Exploring my surroundings.”) | 0.525 |

| SQ12_3 (“Investigating options before making a choice.”) | 0.518 |

| SQ12_4 (“Observing different ways of doing things.”) | 0.506 |

| SQ12_5 (“Probing deeply into questions I have.”) | 0.581 |

| SQ12_6 (“Becoming curious about new opportunities.”) | 0.494 |

| Factor 4: Confidence (4 items) | |

| SQ12_9 (“Taking care to do things well.”) | 0.596 |

| SQ12_10 (“Performing tasks efficiently.”) | 0.615 |

| SQ12_11 (“Learning new skills.”) | 0.511 |

| SQ12_12 (“Working up to my ability.”) | 0.509 |

| Model Fit Indices (First-Order) | χ2/df = 1.643; CFI = 0.936; TLI = 0.925; RMSEA = 0.046; SRMR = 0.0487 |

| Factor and Item (Non-Abbreviated) | EFA Pattern | Final CFA Std. |

|---|---|---|

| Loading | Loading | |

| Factor 1: Extrinsic Satisfaction (js_1) | ||

| R_SQ7_1 (“I am not satisfied with the benefits I receive.”) | 0.902 | 0.889 |

| SQ6_8 (“I am satisfied with my chances for promotion.”) | 0.898 | 0.87 |

| R_SQ7_4 (“There are benefits we do not have which we should have.”) | 0.894 | 0.856 |

| R_SQ6_5 (“There is really too little chance for promotion on my job.”) | 0.823 | 0.816 |

| SQ7_3 (“The benefit package we have is equitable.”) | 0.815 | 0.854 |

| R_SQ7_8 (“I don’t feel my efforts are rewarded the way they should be.”) | 0.81 | 0.869 |

| R_SQ7_7 (“There are few rewards for those who work here.”) | 0.809 | 0.779 |

| R_SQ6_3 (“I feel unappreciated by the organization when I think about what they pay me.”) | 0.806 | 0.794 |

| R_SQ7_6 (“I do not feel that the work I do is appreciated.”) | 0.774 | 0.831 |

| SQ7_5 (“When I do a good job, I receive the recognition for it that I should receive.”) | 0.755 | 0.825 |

| SQ6_4 (“I feel satisfied with my chances for salary increases”) | 0.754 | 0.816 |

| SQ6_7 (“People get ahead as fast here as they do in other places.”) | 0.72 | 0.715 |

| SQ7_2 (“The benefits we receive are as good as most other organizations offer.”) | 0.712 | 0.717 |

| SQ6_6 (“Those who do well on the job stand a fair chance of being promoted.”) | 0.696 | 0.78 |

| Factor 2: Intrinsic Satisfaction (js_2) | ||

| SQ8_6 (“I like doing the things I do at work.”) | 0.847 | 0.855 |

| SQ8_3 (“I enjoy my coworkers.”) | 0.816 | 0.73 |

| SQ8_1 (“I like the people I work with.”) | 0.805 | 0.713 |

| SQ8_8 (“My job is enjoyable.”) | 0.75 | 0.835 |

| SQ8_9 (“Communications seem good within this organization.”) | 0.685 | 0.77 |

| Model Fit Indices | χ2/df = 2.987; CFI = 0.946; TLI = 0.937; RMSEA = 0.080; SRMR = 0.061 | |

| Factor Correlation | 0.814 | |

| Factor (EFA Origin/Theoretical Name) and Item | Original Item Content (Non-Abbreviated) | EFA Pattern Loading (17-Item, n = 155) | Final CFA Std. Loading (9-Item, n = 156) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Comfort with AI (SEAI_1) | |||

| SQ27_4 | “Interacting with AI tech/products, I feel comfortable inside.” | 0.695 | 0.753 |

| SQ26_7 | “I find it easy to get AI tech/products to do what I want.” | 0.644 | 0.516 |

| SQ27_11 | “Interacting with AI tech/products, I feel very relaxed.” | 0.638 | 0.855 |

| SQ27_7 | “I can interact with AI tech/products fluently and pleasantly.” | 0.604 | 0.751 |

| SQ27_2 | “Interacting with AI tech/products, I find it easy.” | 0.593 | 0.72 |

| Factor 2: AI Technological Skills (SEAI_2) | |||

| SQ27_9 | “Using AI tech/products, I am not worried about risks from pressing the wrong button.” | −0.894 | 0.619 |

| SQ27_3 | “Using AI tech/products, I am not worried about damaging it by pressing the wrong button.” | −0.757 | 0.563 |

| SQ27_6 | “Using AI tech/products, there are no operations I don’t understand.” | −0.59 | 0.71 |

| SQ27_10 | “The professional terms of AI tech/products do not confuse me.” | −0.479 | 0.855 |

| Model Fit Indices (Final 9-item, 2-factor CFA, n = 156) χ2/df = 1.894; CFI = 0.967; TLI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.076 | |||

| Item ID | Original Item Content (Non-Abbreviated) | EFA Factor Loading (5-Item, n = 155) | Final CFA Std. Loading (5-Item, n = 156) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ2_3 | “Learning to use specific functions of an AI tech/product makes me anxious.” | 0.798 | 0.77 | |

| SQ2_1 | “Learning to understand all special functions… makes me anxious.” | 0.791 | 0.893 | |

| SQ2_2 | “Learning to use AI tech/products makes me anxious.” | 0.776 | 0.825 | |

| SQ2_4 | “I am afraid that an AI tech/product may replace humans.” | 0.677 | 0.565 | |

| SQ2_5 | “I am afraid that widespread use of humanoid robots will take jobs away…” | 0.626 | 0.512 | |

| Model Fit Indices (Final 5-item, 1-factor CFA, n = 156) | χ2/df = 1.666; CFI = 0.993; TLI = 0.983; RMSEA = 0.066; Bollen–Stine p = 0.151 | |||

| Factor (EFA Origin/Theoretical Name) and Item | EFA Pattern Loading | Final CFA Std. Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: WE | ||

| SQ37_5 (I am enthusiastic about my job.) | 0.959 | 0.916 |

| SQ37_4 (At my job, I feel strong and vigorous.) | 0.74 | 0.912 |

| SQ37_1 (At my work, I feel bursting with energy.) | 0.782 | 0.885 |

| SQ37_8 (My job inspires me.) | 0.68 | 0.864 |

| SQ37_2 (I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose.) | 0.912 | 0.85 |

| SQ37_9 (When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work.) | 0.74 | 0.822 |

| SQ38_1 (I am proud of the work that I do.) | 0.887 | 0.801 |

| SQ38_5 (I get carried away when I am working.) | 0.641 | 0.762 |

| SQ37_10 (I feel happy when I am working intensely.) | 0.641 | 0.758 |

| SQ38_2 (I am immersed in my work.) | 0.753 | 0.739 |

| SQ38_6 (At my job, I am very resilient, mentally.) | 0.647 | 0.718 |

| SQ37_3 (Time flies when I am working.) | 0.664 | 0.674 |

| SQ38_8 (At my work, I always persevere, when things do not go well.) | 0.465 | 0.65 |

| Model Fit Indices χ2/df = 1.769; CFI = 0.975; TLI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.070; SRMR = 0.065} | ||

| Covaried Error Terms multicolumn{SQ37_1,SQ37_4(Energy/Vigor)} multicolumn{SQ38_2, SQ38_5(Immersion)} multicolumn{SQ37_2,SQ38_1(Meaning/Pride)} multicolumn{SQ37_9, SQ37_10(Positive Affect)} | ||

References

- Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Hazell, J., & Restrepo, P. (2022). Artificial intelligence and jobs: Evidence from online vacancies. Journal of Labor Economics, 40(S1), S293–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. H. J., & Mai, X. (2015). The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Hu, W., & Wei, X. (2025). From anxiety to action: Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence anxiety and artificial intelligence self-efficacy on motivated learning of undergraduate students. Interactive Learning Environments, 33(4), 3162–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Ke, J., Zhang, X. E., & Chen, J. (2025). The impact of AI anxiety on employees’ work passion: A moderated mediated effect model. Acta Psychologica, 260, 105487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntella, O., König, J., & Stella, L. (2023). Artificial intelligence and workers’ well-being. No. 16485. IZA Discussion Papers. [Google Scholar]

- Glikson, E., & Woolley, A. W. (2020). Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzko, D., Siemund, K., & Sterner, P. (2024). Evaluating model fit of measurement models in confirmatory factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 84(1), 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(1), 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 127–147). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, K. E., & Kim, D. (2021). College students’ adult attachment and career adaptability: Mediation by maladaptive perfectionism and moderation by gender. Journal of Career Development, 48(4), 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C. S. (2018). A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., Podsakoff, N. P., Shaw, J. C., & Rich, B. L. (2010). The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. J., Kim, M. J., & Lee, J. (2024). Examining the impact of work overload on cybersecurity behavior: Highlighting self-efficacy in the realm of artificial intelligence. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17146–17162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. J., & Lee, J. (2024). The mental health implications of artificial intelligence adoption: The crucial role of self-efficacy. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, F. T., Gardner, D. M., Nye, C. D., & Prasad, J. J. (2023). The five-factor career adapt-abilities scale’s predictive and incremental validity with work-related and life outcomes. Journal of Career Development, 50(4), 860–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, F. T., & Ott-Holland, C. (2014). Career adaptability: Theory and measurement. In Individual adaptability to changes at work (pp. 95–114). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., & Li, Y. (2025). Examining the double-edged sword effect of AI usage on work engagement: The moderating role of core task characteristics substitution. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E. J., & Savickas, M. L. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale-USA form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. (2024). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What it means, how to respond. In Handbook of research on strategic leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (pp. 29–34). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M. N., Zhang, L., Asif, M., Alshdaifat, S. M., & Hanaysha, J. R. (2025). Artificial intelligence and employee outcomes: Investigating the role of job insecurity and technostress in the hospitality industry. Acta Psychologica, 253, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sony, M., & Mekoth, N. (2022). Employee adaptability skills for Industry 4.0 success: A road map. Production & Manufacturing Research, 10(1), 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Social cognitive theory and self-efficacy: Goin beyond traditional motivational and behavioral approaches. Organizational Dynamics, 26(4), 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L., & Oviatt, S. (2021). A taxonomy of social errors in human-robot interaction. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction (THRI), 10(2), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. (2022). Adoption and use of AI tools: A research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Annals of Operations Research, 308(1), 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D., Christofi, M., Pereira, V., Tarba, S., Makrides, A., & Trichina, E. (2022). Artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced technologies and human resource management: A systematic review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(6), 1237–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Mei, M., Xie, Y., Zhao, Y., & Yang, F. (2021). Proactive personality as a predictor of career adaptability and career growth potential: A view from conservation of resources theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 699461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Y., & Chuang, Y. W. (2024). Artificial intelligence self-efficacy: Scale development and validation. Education and Information Technologies, 29(4), 4785–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., Ford, L. R., & Nguyen, N. (2004). Basic and advanced measurement models for confirmatory factor analysis. In Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 366–389). Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yalabik, Z. Y., Rayton, B. A., & Rapti, A. (2017). Facets of job satisfaction and work engagement. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5(3), 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Guan, X., Zhou, X., & Lu, J. (2019). The effect of career adaptability on career planning in reaction to automation technology. Career Development International, 24(6), 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Gan, Y. (2005). The Chinese version of Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES): An examination of reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 13(3), 268–270. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Dimension | Items | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Adaptability | Overall | 18 | 0.857 | 0.858 [0.835, 0.881] |

| Concern | 5 | 0.709 | 0.717 [0.646, 0.789] | |

| Control | 3 | 0.769 | 0.774 [0.734, 0.814] | |

| Curiosity | 6 | 0.705 | 0.705 [0.653, 0.757] | |

| Confidence | 4 | 0.697 | 0.693 [0.640, 0.766] | |

| Job Satisfaction | Overall | 19 | 0.967 | 0.968 [0.963, 0.974] |

| Extrinsic Satisfaction | 14 | 0.966 | 0.964 [0.958, 0.970] | |

| Intrinsic Satisfaction | 5 | 0.894 | 0.896 [0.878, 0.914] | |

| AI Anxiety | Overall | 5 | 0.850 | 0.841 [0.812, 0.869] |

| Self-Efficacy in AI Use (SEAI) | Overall | 9 | 0.855 | 0.893 [0.875, 0.911] |

| Comfort with AI | 5 | 0.841 | 0.879 [0.859, 0.899] | |

| AI Technological Skills | 4 | 0.807 | 0.782 [0.744, 0.821] | |

| Work Engagement | Overall | 13 | 0.957 | 0.750 [0.702, 0.798] |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-factor theoretical model | 2874.785 | 1916 | 1.5 | 0.928 | 0.924 | 0.040 [0.037, 0.043] | 0.0605 | 3202.785 | 3816.111 |

| Single-factor model | 6055.792 | 1941 | 3.12 | 0.69 | 0.678 | 0.083 [0.080, 0.085] | 0.0961 | 6333.792 | 6853.623 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CA | 4.13 | 0.39 | - | |||||||||

| 2. Control | 3.94 | 0.55 | 0.540 ** | - | ||||||||

| 3. Concern | 4.2 | 0.55 | 0.832 ** | 0.281 ** | - | |||||||

| 4. Curiosity | 4.14 | 0.48 | 0.857 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.579 ** | - | ||||||

| 5. Confidence | 4.23 | 0.46 | 0.797 ** | 0.354 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.590 ** | - | |||||

| 6. JS1 | 3.53 | 1.14 | 0.388 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.332 ** | - | ||||

| 7. JS2 | 4.21 | 0.98 | 0.447 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.742 ** | - | |||

| 8. SEAI1 | 5.63 | 0.6 | 0.383 ** | 0.172 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.349 ** | - | ||

| 9. SEAI2 | 4.71 | 1.11 | 0.295 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.211 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.483 ** | - | |

| 10. AIA | 2.52 | 0.87 | −0.269 ** | −0.151 ** | −0.140 * | −0.237 ** | −0.310 ** | −0.391 ** | −0.341 ** | −0.358 ** | −0.385 ** | - |

| 11. WE | 4.72 | 1.12 | 0.570 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.692 ** | 0.749 ** | 0.393 ** | 0.291 ** | −0.320 ** |

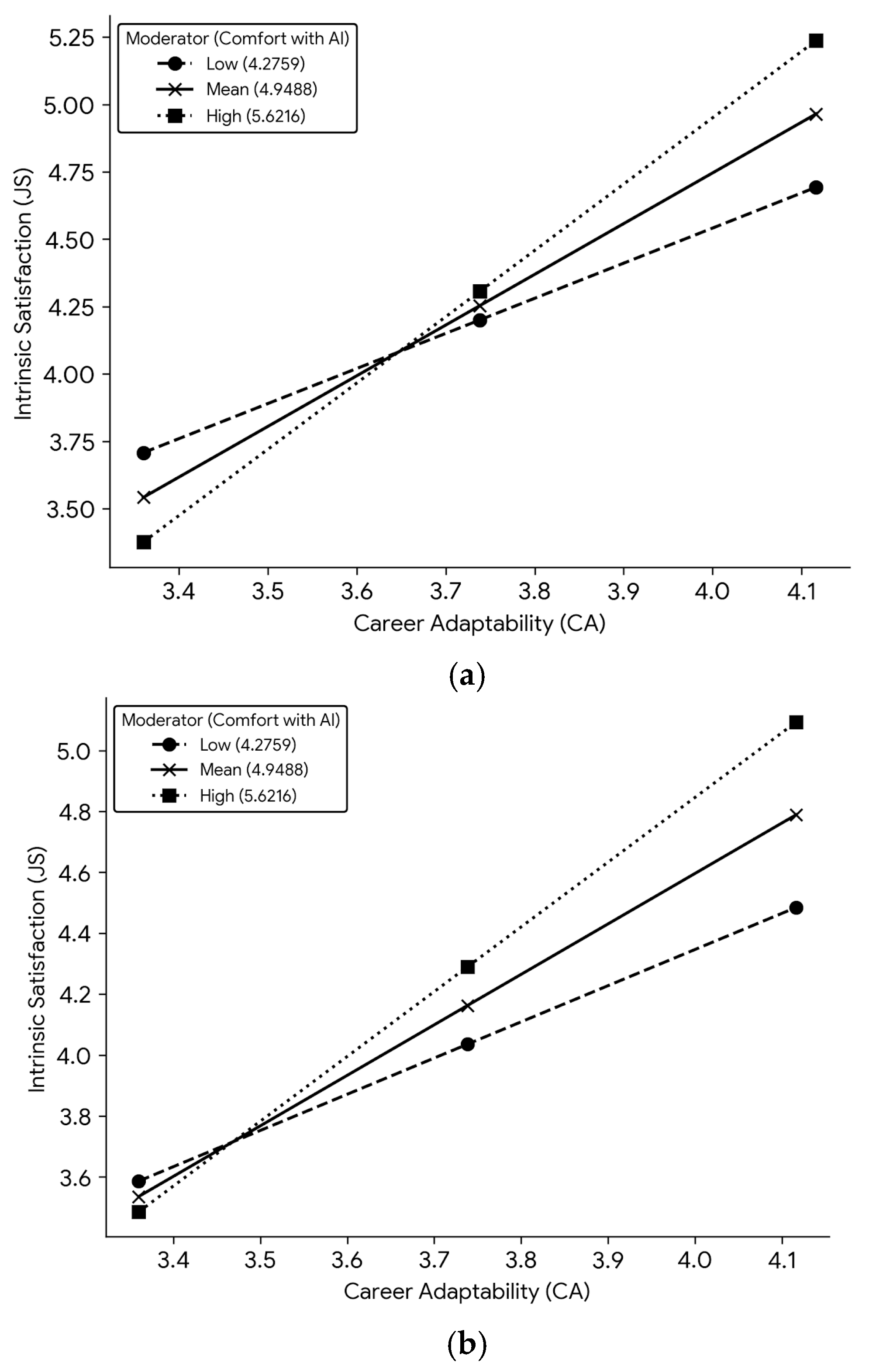

| (a) | |||||||

| Outcome | Predictor | b | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Model 1: Outcome = Extrinsic Satisfaction (JS1)/W = Comfort with AI (SEAI1) | CA (X) | −4.9042 | 2.1992 | −2.2300 | 0.0265 | −9.2320 | −0.5764 |

| SEAI1 (W) | −5.1477 | 1.6639 | −3.0938 | 0.0022 | −8.4221 | −1.8734 | |

| AIA (Z) | −5.7176 | 2.4176 | −2.3650 | 0.0187 | −10.4753 | −0.9600 | |

| CA × SEAI1 (Int_1) | 1.3880 | 0.4293 | 3.2333 | 0.0014 | 0.5432 | 2.2328 | |

| CA × AIA (Int_2) | 1.4051 | 0.6436 | 2.1833 | 0.0298 | 0.1386 | 2.6716 | |

| SEAI1 × AIA (Int_3) | 1.3401 | 0.5117 | 2.6188 | 0.0093 | 0.3331 | 2.3471 | |

| CA × SEAI1 × AIA (Int_4) | −0.3509 | 0.1303 | −2.6922 | 0.0075 | −0.6074 | −0.0944 | |

| Y = Work Engagement (WE) | CA (Direct Effect) | 1.2912 | 0.1082 | 11.9354 | 0.0000 | 1.0783 | 1.5041 |

| JS1 (Mediator) | 0.5400 | 0.0365 | 14.7740 | 0.0000 | 0.4680 | 0.6119 | |

| Model 2: Outcome = Extrinsic Satisfaction (JS1)/W = AI Technological Skills (SEAI2) | CA (X) | −3.5570 | 2.2347 | −1.5917 | 0.1124 | −7.9580 | 0.8439 |

| SEAI2 (W) | −5.5428 | 1.6851 | −3.2892 | 0.0011 | −8.8590 | −2.2266 | |

| AIA (Z) | −4.1837 | 1.8214 | −2.2970 | 0.0223 | −7.7680 | −0.5994 | |

| CA × SEAI2 (Int_1) | 1.5080 | 0.4319 | 3.4917 | 0.0006 | 0.6581 | 2.3580 | |

| CA × AIA (Int_2) | 1.0282 | 0.4752 | 2.1636 | 0.0313 | 0.0930 | 1.9634 | |

| SEAI2 × AIA (Int_3) | 1.3196 | 0.5678 | 2.3242 | 0.0208 | 0.2023 | 2.4369 | |

| CA × SEAI2 × AIA (Int_4) | −0.3502 | 0.1462 | −2.3958 | 0.0172 | −0.6379 | −0.0626 | |

| Y = Work Engagement (WE) | CA (Direct Effect) | 1.2912 | 0.1082 | 11.9354 | 0.0000 | 1.0783 | 1.5041 |

| JS1 (Mediator) | 0.5400 | 0.0365 | 14.7740 | 0.0000 | 0.4680 | 0.6119 | |

| Model 3: Outcome = Intrinsic Satisfaction (JS2)/W = Comfort with AI (SEAI1) | SEAI1 (W) | −2.9548 | 1.7984 | −1.6430 | 0.1014 | −6.4938 | 0.5841 |

| AIA (Z) | −3.8508 | 1.3600 | −2.8315 | 0.0049 | −6.5270 | −1.1746 | |

| CA × SEAI1 (Int_1) | −3.7399 | 1.9751 | −1.8935 | 0.0592 | −7.6265 | 0.1467 | |

| CA × AIA (Int_2) | 1.0223 | 0.3511 | 2.9115 | 0.0039 | 0.3313 | 1.7132 | |

| SEAI1 × AIA (Int_3) | 0.7756 | 0.5265 | 1.4732 | 0.1417 | −0.2604 | 1.8117 | |

| CA × SEAI1 × AIA (Int_4) | 0.9571 | 0.4189 | 2.2846 | 0.0230 | 0.1327 | 1.7815 | |

| SEAI1 (W) | −0.2171 | 0.1067 | −2.0341 | 0.0428 | −0.4272 | −0.0071 | |

| Y = Work Engagement (WE) | JS2 (Mediator) | 0.7392 | 0.0905 | 8.1725 | 0.0000 | 0.5613 | 0.9172 |

| JS2 (Mediator) | 0.8684 | 0.0344 | 25.2323 | 0.0000 | 0.8007 | 0.9361 | |

| (b) | |||||||

| Model | Index | Effect Size | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| Model 1 (M = JS1, W = SEAI1) | Overall Index (X × W × Z) | −0.1895 * | 0.0919 | −0.4243 | −0.0584 | ||

| Conditional Index by AIA (Z) | |||||||

| Low AI anxiety | 0.6083 * | 0.2286 | 0.2407 | 1.1574 | |||

| Moderate AI anxiety | 0.4654 * | 0.1772 | 0.1737 | 0.8775 | |||

| High AI anxiety | 0.3225 * | 0.1419 | 0.0602 | 0.6212 | |||

| Model 2 (M = JS1, W = SEAI2) | Overall Index (X × W × Z) | −0.1891 * | 0.0849 | −0.3901 | −0.0575 | ||

| Conditional Index by AIA (Z) | |||||||

| Low AI anxiety | 0.6734 * | 0.1988 | 0.3097 | 1.0930 | |||

| Moderate AI anxiety | 0.5307 * | 0.1591 | 0.2263 | 0.8559 | |||

| High AI anxiety | 0.3881 * | 0.1388 | 0.1050 | 0.6476 | |||

| Model 3 (M = JS2, W = SEAI1) | Overall Index (X × W × Z) | −0.1886 * | 0.1248 | −0.5106 | −0.0156 | ||

| Conditional Index by AIA (Z) | |||||||

| Low AI anxiety | 0.7472 * | 0.3158 | 0.2825 | 1.5341 | |||

| Moderate AI anxiety | 0.6050 * | 0.2425 | 0.2342 | 1.1938 | |||

| High AI anxiety | 0.4628 * | 0.1888 | 0.1361 | 0.8738 | |||

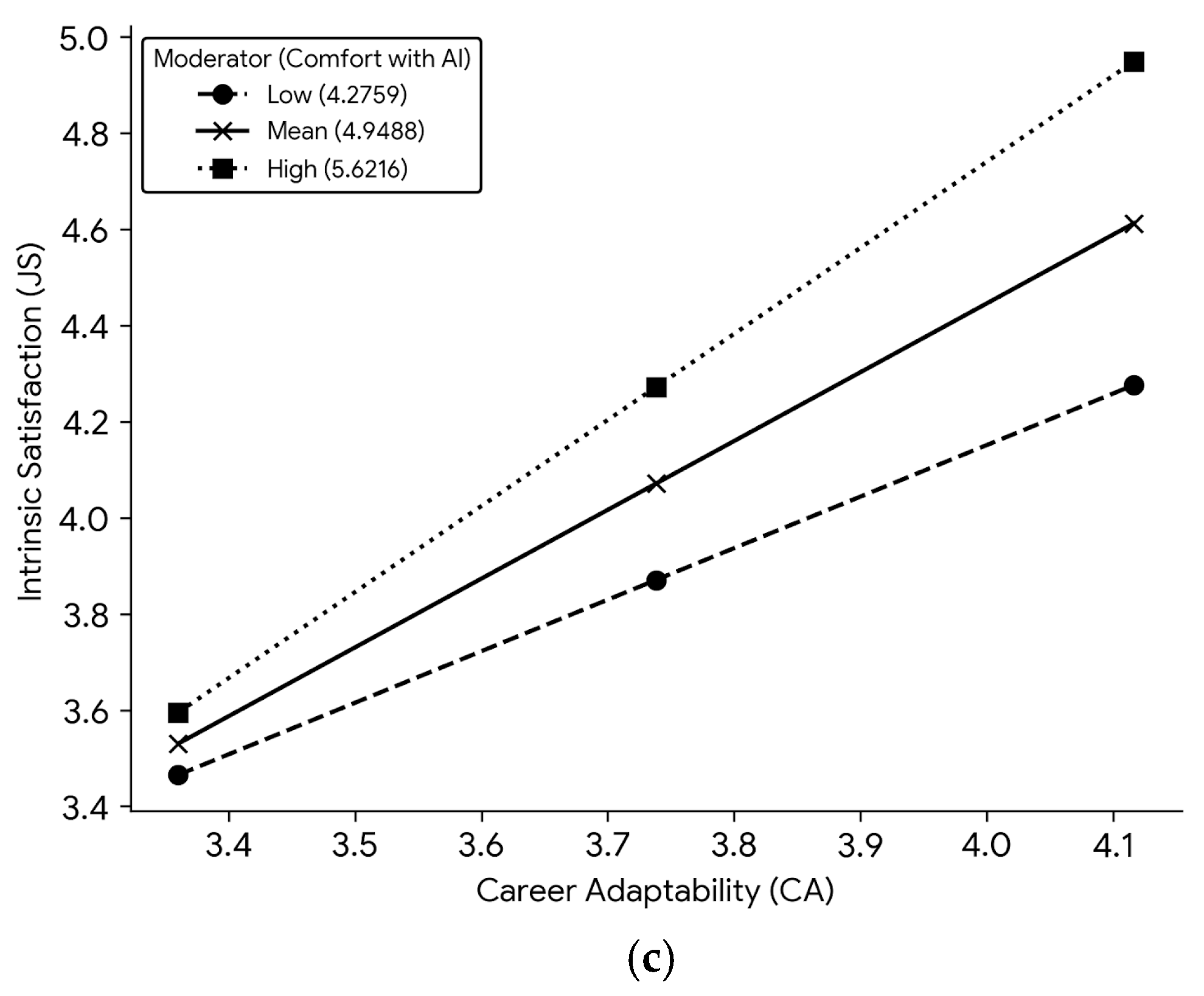

| (a) | |||||

| AI Technological Skills (W) | AIA (Z) | Effect Size | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Low | Low | 0.5183 | 0.2689 | −0.0459 | 1.0109 |

| Low | Middle | 0.4795 * | 0.1696 | 0.1231 | 0.7947 |

| Low | High | 0.4407 * | 0.1362 | 0.1674 | 0.7037 |

| Middle | Low | 0.9276 * | 0.2245 | 0.4946 | 1.3712 |

| Middle | Middle | 0.7927 * | 0.1466 | 0.5132 | 1.0723 |

| Middle | High | 0.6578 * | 0.1594 | 0.3409 | 0.9640 |

| High | Low | 1.3369 * | 0.2752 | 0.8248 | 1.9035 |

| High | Middle | 1.1058 * | 0.2066 | 0.7278 | 1.5362 |

| High | High | 0.8748 * | 0.2247 | 0.4218 | 1.3084 |

| (b) | |||||

| AI Technological Skills (W) | AIA (Z) | Effect Size | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Low | Low | 0.3288 | 0.2515 | −0.1782 | 0.8187 |

| Low | Middle | 0.3587 * | 0.1598 | 0.0355 | 0.6733 |

| Low | High | 0.3885 * | 0.1172 | 0.1567 | 0.6202 |

| Middle | Low | 0.8461 * | 0.1843 | 0.4992 | 1.2184 |

| Middle | Middle | 0.7664 * | 0.1244 | 0.5261 | 1.0136 |

| Middle | High | 0.6867 * | 0.1530 | 0.3687 | 0.9723 |

| High | Low | 1.3633 * | 0.2266 | 0.9249 | 1.8192 |

| High | Middle | 1.1740 * | 0.1878 | 0.8095 | 1.5412 |

| High | High | 0.9848 * | 0.2362 | 0.4884 | 1.4150 |

| (c) | |||||

| Comfort with AI (W) | AIA (Z) | Effect Size | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Low | Low | 1.1310 * | 0.3869 | 0.3083 | 1.8057 |

| Low | Middle | 1.0309 * | 0.2466 | 0.5054 | 1.4783 |

| Low | High | 0.9309 * | 0.2028 | 0.5262 | 1.3202 |

| Middle | Low | 1.6338 * | 0.3128 | 1.0170 | 2.2249 |

| Middle | Middle | 1.4380 * | 0.2036 | 1.0286 | 1.8264 |

| Middle | High | 1.2423 * | 0.2245 | 0.7782 | 1.6636 |

| High | Low | 2.1365 * | 0.3691 | 1.4226 | 2.8684 |

| High | Middle | 1.8451 * | 0.2745 | 1.3235 | 2.4020 |

| High | High | 1.5537 * | 0.3032 | 0.9310 | 2.1307 |

| Path | Predictor | Outcome | b | BCa 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | CA (2nd Order) | JS1 | 1.249 *** | [0.901, 1.885] |

| a2 | CA (2nd Order) | JS2 | 1.361 *** | [1.023, 1.967] |

| b1 | JS1 | WE | 0.107 | [−0.030, 0.250] |

| b2 | JS2 | WE | 0.716 *** | [0.548, 0.912] |

| c | CA (2nd Order) | WE | 0.715 *** | [0.385, 1.396] |

| Path | Total Indirect Effect (b) | BCa 95% CI | Bootstrap p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA → JS1, JS2 → WE | 1.109 *** | [0.796, 1.598] | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leong, F.T.L.; Li, X.; Chen, E.M. The Relationship Between Career Adaptability and Work Engagement Among Young Chinese Workers: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Moderating Effects of Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy and Anxiety. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121682

Leong FTL, Li X, Chen EM. The Relationship Between Career Adaptability and Work Engagement Among Young Chinese Workers: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Moderating Effects of Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy and Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121682

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeong, Frederick Theen Lok, Xuan Li, and Emma Mingjing Chen. 2025. "The Relationship Between Career Adaptability and Work Engagement Among Young Chinese Workers: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Moderating Effects of Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy and Anxiety" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121682

APA StyleLeong, F. T. L., Li, X., & Chen, E. M. (2025). The Relationship Between Career Adaptability and Work Engagement Among Young Chinese Workers: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Moderating Effects of Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy and Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121682