Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use Among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use

1.2. The Mediation Effect of Rumination

1.3. The Mediation Effect of Social Anxiety

1.4. The Mediation Effect of Rumination and Social Anxiety

1.5. Heterogeneity of Childhood Trauma

1.6. Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Assessment

2.2.1. Childhood Abuse

2.2.2. Childhood Neglect

2.2.3. Problematic Smartphone Use

2.2.4. Rumination

2.2.5. Social Anxiety

2.3. Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Common Methods Bias and Collinearity Test

3.3. Test for the Direct and Chain Mediating Effects

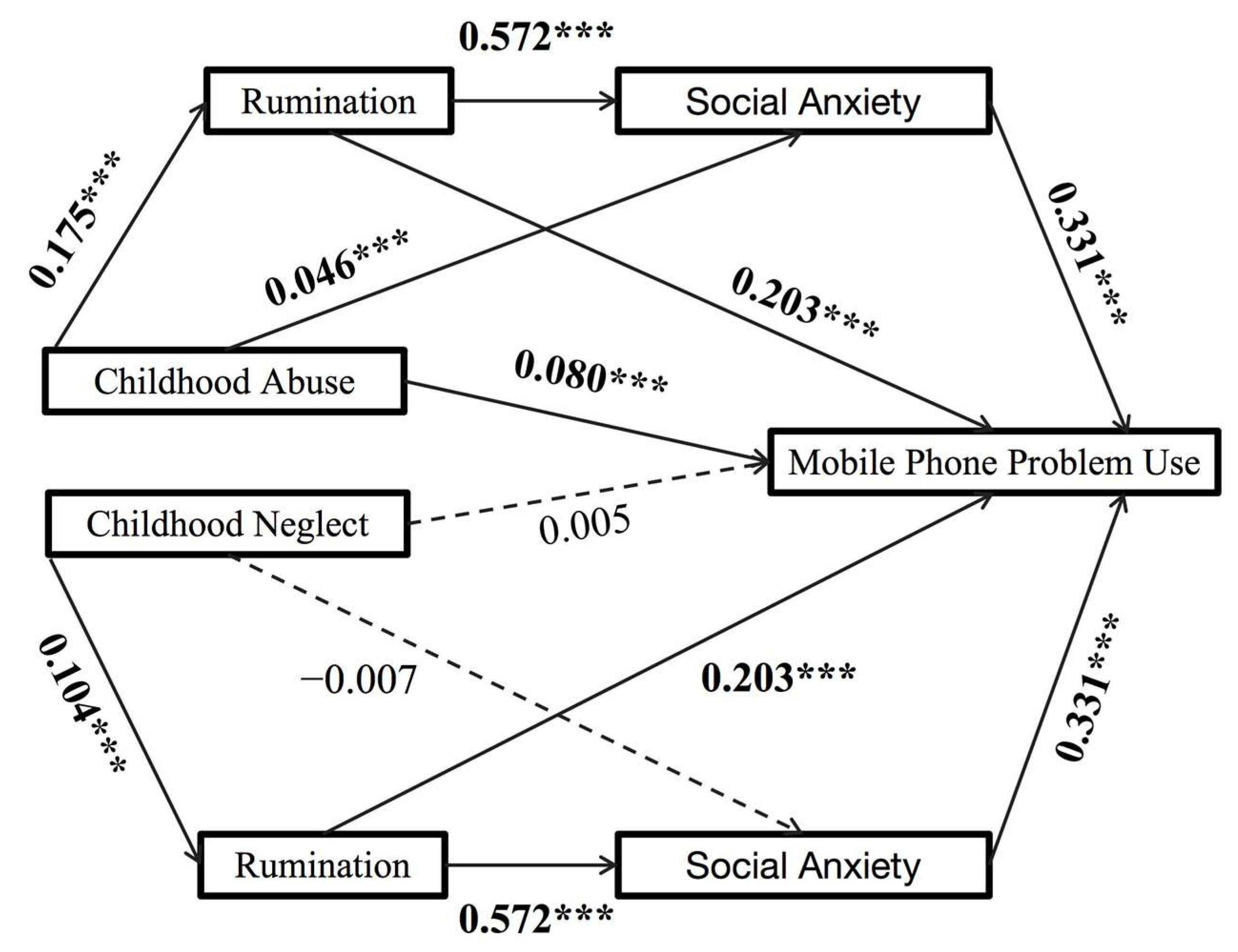

3.4. Identifying the Childhood Trauma Profiles

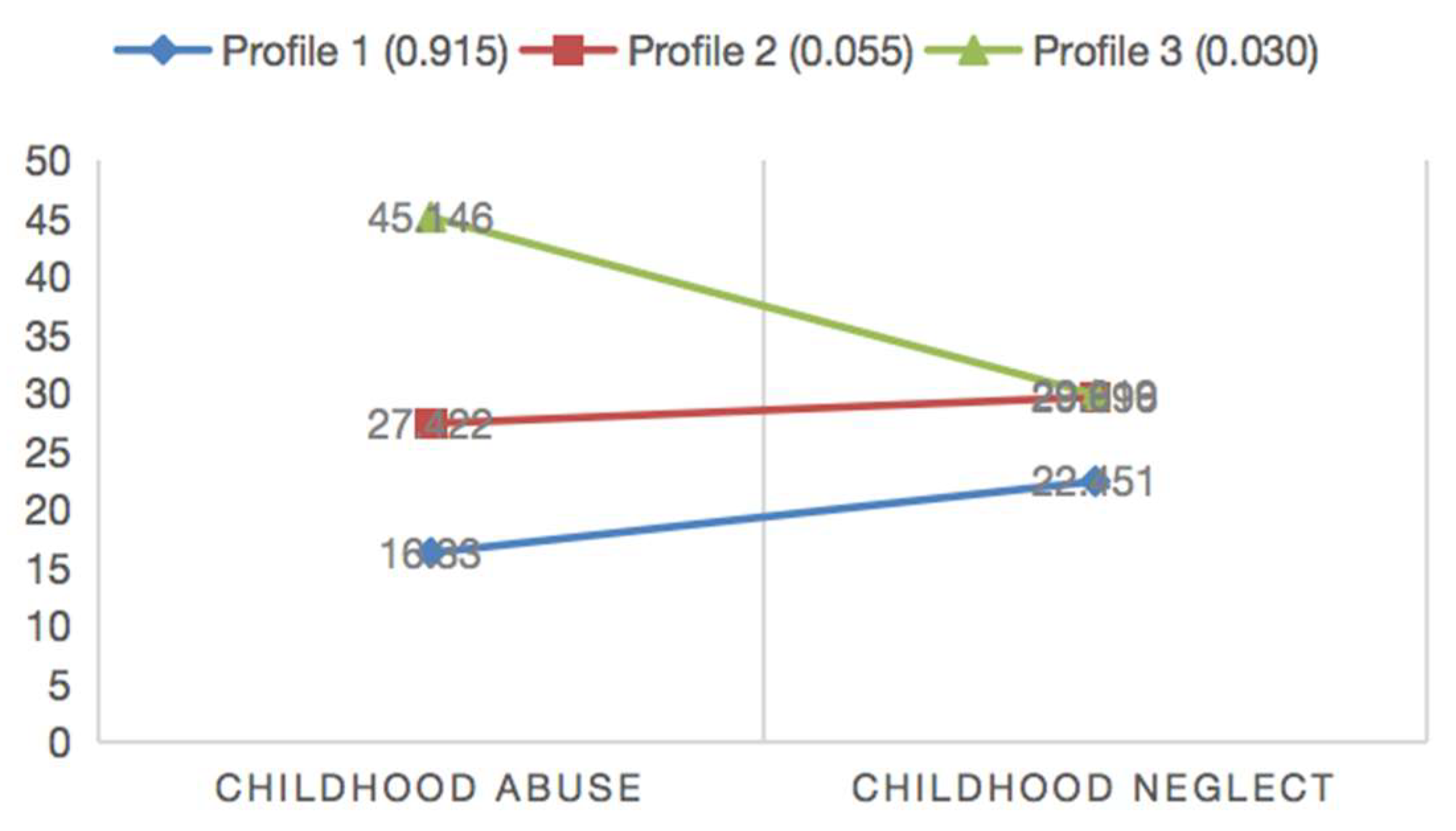

3.5. The Chain Mediating Effects from the Person-Centred Perspective

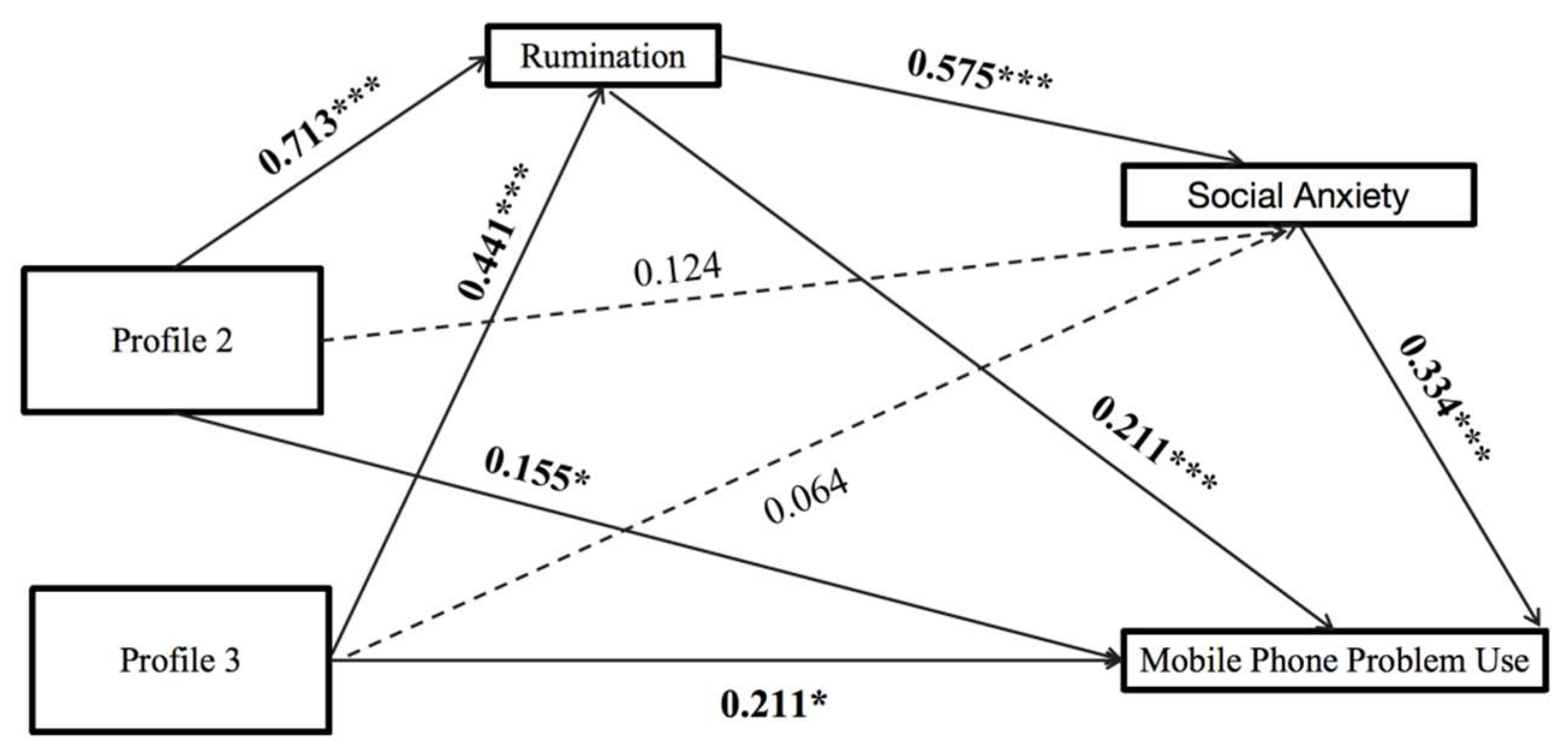

4. Discussion

4.1. Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use

4.2. The Mediation Effect of Rumination

4.3. The Mediation Effect of Social Anxiety

4.4. The Different Profiles of Childhood Trauma

4.5. Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety Between Trauma Profiles and PSU

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnes, S. J., Pressey, A. D., & Scornavacca, E. (2019). Mobile ubiquity: Understanding the relationship between cognitive absorption, smartphone addiction and social network services. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., & Desmond, D. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A., & Phillips, J. G. (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, L. C., Heimberg, R. G., Blanco, C., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and social anxiety disorder: Implications for symptom severity and response to pharmacotherapy. Depression and Anxiety, 29(2), 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., Liu, J., Cao, X., Duan, S., Wen, S., Zhang, S., Xu, J., Lin, L., Xue, Z., & Lu, J. (2020). The relationship between mobile phone use and suicide-related behaviors among adolescents: The mediating role of depression and interpersonal problems. Journal of Affective Disorders, 269, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, A. Y., Hartanto, A., Wan, T. S., Teo, S. S., Sim, L., & Kasturiratna, K. S. (2025). The impact of childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect on suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychiatry Research Communications, 5, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S. M., Stockdale, L., & Summers, K. (2019). Problematic cell phone use, depression, anxiety, and self-regulation: Evidence from a three year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C. F., Elith, J., Bacher, S., Buchmann, C., Carl, G., Carré, G., Marquéz, J. R. G., Gruber, B., Lafourcade, B., Leitão, P. J., & Leitão, P. J. (2013). Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography, 36(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emirtekin, E., Balta, S., Sural, İ., Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., & Billieux, J. (2019). The role of childhood emotional maltreatment and body image dissatisfaction in problematic smartphone use among adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 271, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X., Wu, Z., Wen, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, D., Yu, L., Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Chen, L., Liu, H., & Liu, H. (2023). Rumination mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 273(5), 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M., & Gallus, K. (2020). Emotional support as a mechanism linking childhood maltreatment and adult’s depressive and social anxiety symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbard, G. O. (2009). Textbook of psychotherapeutic treatments. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L., Yang, C., Yang, X., Chu, X., Liu, Q., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Negative emotion and problematic mobile phone use: The mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of social support. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 25(1), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J., Bao, L., Wang, H., Wang, J., Gao, T., & Lei, L. (2022). Does childhood maltreatment increase the subsequent risk of problematic smartphone use among adolescents? A two-wave longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors, 129, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, W. A. (1959). Three multivariate models: Factor analysis, latent structure analysis, and latent profile analysis. Psychometrika, 24(3), 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X., & Yang, H.-f. (2009). Chinese version of Nolen-Hoeksema ruminative responses scale (RRS) used in 912 college students: Reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(5), 550–551. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. University of Kansas, KS. [Google Scholar]

- Horwood, S., & Anglim, J. (2019). Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L. E., Meer, E. A., Gillan, C. M., Hsu, M., & Daw, N. D. (2022). Increased and biased deliberation in social anxiety. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I., Krabbendam, L., Bak, M., Hanssen, M., Vollebergh, W., de Graaf, R., & van Os, J. (2004). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(1), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L. (2024). Childhood emotional abuse and depression among Chinese adolescent sample: A mediating and moderating dual role model of rumination and resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 149, 106607. [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A. M., & Stone, W. L. (1993). Social anxiety scale for children-revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 22(1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebherr, M., Schubert, P., Antons, S., Montag, C., & Brand, M. (2020). Smartphones and attention, curse or blessing?—A review on the effects of smartphone usage on attention, inhibition, and working memory. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Zhang, Z., & Chen, L. (2020). Mediating effect of neuroticism and negative coping style in relation to childhood psychological maltreatment and smartphone addiction among college students in China. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Q., Yang, X.-J., Zhu, X.-W., & Zhang, D.-J. (2021). Attachment anxiety, loneliness, rumination and mobile phone dependence: A cross-sectional analysis of a moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 40(10), 5134–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.-D., Hong, W., Ding, Y., Oei, T. P., Zhen, R., Jiang, S., & Liu, J. (2019). Psychological distress and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents: The mediating role of maladaptive cognitions and the moderating role of effortful control. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovallo, W. R. (2006). Cortisol secretion patterns in addiction and addiction risk. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 59(3), 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S., Huang, Y., & Ma, Y. (2020). Childhood maltreatment and mobile phone addiction among Chinese adolescents: Loneliness as a mediator and self-control as a moderator. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Ruminative self-focus, negative life events, and negative affect. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(9), 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, I. B., & Lee, S. (2025). Perceived parental depression and adolescents’ excessive smartphone use: The mediating role of adolescents’ depression and anxiety. The Social Science Journal, 62(3), 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. C., Wu, L. H., Lam, H. Y., Lam, L. K., Nip, P. Y., Ng, C. M., Leung, K. C., & Leung, S. F. (2020). The relationships between mobile phone use and depressive symptoms, bodily pain, and daytime sleepiness in Hong Kong secondary school students. Addictive Behaviors, 101, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y., Zhou, H., Zhang, B., Mao, H., Hu, R., & Jiang, H. (2022). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F., & Hermans, D. (2008). On the mediating role of subtypes of rumination in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depressed mood: Brooding versus reflection. Depression and Anxiety, 25(12), 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G., Li, J., Zhang, Q., & Niu, X. (2022). The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: A three-level meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rrustemi, V., Hasani, E., Jusufi, G., & Mladenović, D. (2021). Social media in use: A uses and gratifications approach. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 26(1), 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicheng, X., Bin, Z., Yongzhi, J., Huaibin, J., & Yun, C. (2021). Global prevalence of mobile phone addiction: A meta-analysis. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 19(6), 802. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, G. C., Bywaters, P. W., & Kennedy, E. (2023). A review of the relationship between poverty and child abuse and neglect: Insights from scoping reviews, systematic reviews and meta--analyses. Child Abuse Review, 32(2), e2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topino, E., & Gori, A. (2025). Childhood neglect and its effect on self-conception and attachment in adulthood: A structural equation model. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, J. P., Tan, A. P., Broeckman, B. B., Gluckman, P. D., Chong, Y. S., Chen, H., Fortier, M. V., Meaney, M. J., & Callaghan, B. L. (2023). Effects of maternal childhood trauma on child emotional health: Maternal mental health and frontoamygdala pathways. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(3), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Liu, B., Hong, S., & Zou, H. (2025). Longitudinal relationships between childhood emotional maltreatment and depression in Chinese university students: The roles of attention bias and expressive suppression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. A., & Kibowski, F. (2016). Latent class analysis and latent profile analysis. In L. A. Jason, & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (pp. 143–151). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S. (2013). The effects of parental abuse and neglect, and children’s peer attachment, on mobile phone dependency. Human Ecology Research, 51(6), 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Q., Liu, F., Chan, K. Q., Wang, N.-X., Zhao, S., Sun, X., Shen, W., & Wang, Z.-J. (2022). Childhood psychological maltreatment and internet gaming addiction in Chinese adolescents: Mediation roles of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y., He, Q., & Yuan, R. (2023). Childhood maltreatment affects mobile phone addiction from the perspective of attachment theory. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(6), 3536–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Shen, Y., & Wu, J. (2024). Cumulative childhood trauma and mobile phone addiction among chinese college students: Role of self-esteem and self-concept clarity as serial mediators. Current Psychology, 43(6), 5355–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J. C., & Widom, C. S. (2014). Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R., Zhang, J.-J., Liu, Y.-D., Chen, H.-B., Wang, S.-B., Jia, F.-J., & Hou, C.-L. (2023). Internet addiction in adolescent psychiatric patient population: A hospital-based study from China. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(1), 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X., Xu, Q., Inglés, C. J., Hidalgo, M. D., & La Greca, A. M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the social anxiety scale for adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(2), 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H., Tang, D., Chen, Z., Wang, E. C., & Zhang, W. (2024). The effect of social anxiety, impulsiveness, self--esteem on non--suicidal self--injury among college students: A conditional process model. International Journal of Psychology, 59(6), 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J. B., & Abbott, M. J. (2012). Self-perception and rumination in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(4), 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood abuse | 17.82 ± 5.90 | — | ||||

| Childhood neglect | 23.08 ± 7.31 | 0.278 *** | — | |||

| Rumination | 34.94 ± 13.12 | 0.272 *** | 0.207 *** | — | ||

| Social anxiety | 6.30 ± 4.94 | 0.204 *** | 0.130 *** | 0.606 *** | — | |

| PSU | 24.67 ± 8.33 | 0.208 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.470 *** | — |

| Number of Profiles | AIC | BIC | aBIC | LMRT | BLRT | Entropy | Group Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 33,153.529 | 33,194.880 | 33,172.639 | 2622.170 *** | 2732.708 *** | 0.993 | 2586/121 |

| 3 | 32,155.823 | 32,214.896 | 32,183.123 | 963.106 * | 1003.706 *** | 0.983 | 2485/150/82 |

| 4 | 31,795.711 | 31,872.505 | 31,831.200 | 351.304 | 366.113 *** | 0.958 | 2358/201/79/79 |

| Total Sample (n = 2717) | M (SD) | Profile 1 (n = 2485) | Profile 2 (n = 150) | Profile 3 (n = 82) | F | Post hoc Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Abuse | 17.82 (5.90) | 16.33 (1.86) | 27.53 (3.69) | 45.23(5.65) | 8371.56 *** | P3 > P2, P1 *** |

| 15–75 | 15–24 | 23–36 | 37–75 | P2 > P1 *** | ||

| Childhood Neglect | 23.08 (7.31) | 22.45 (7.14) | 29.81 (6.32) | 29.88 (3.43) | 117.60 *** | P3, P2 > P1 *** |

| 10–50 | 10–43 | 13–42 | 20–50 | P2 = P3 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile1 | — | |||||

| Profile2 | −0.860 *** | — | ||||

| Profile3 | −0.491 *** | 0.011 | — | |||

| Rumination | −0.269 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.073 *** | — | ||

| Social anxiety | −0.209 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.616 *** | — | |

| PSU | −0.214 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.087 *** | 0.433 *** | 0.469 *** | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zou, H. Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use Among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121676

Deng C, Liu J, Wu X, Wang X, Zheng Z, Zhang W, Zou H. Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use Among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121676

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Caixia, Jingxing Liu, Xiaoqian Wu, Xiaoya Wang, Zhiying Zheng, Wei Zhang, and Hongyu Zou. 2025. "Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use Among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121676

APA StyleDeng, C., Liu, J., Wu, X., Wang, X., Zheng, Z., Zhang, W., & Zou, H. (2025). Childhood Trauma and Problematic Smartphone Use Among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Rumination and Social Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121676