3.1. Interviews and Ecological Maps by Professionals

The first section of the results presents the conclusions drawn from the interviews conducted and the ecological maps developed with internal staff. The preliminary analytical insights, initially identified by the research team, were subsequently shared with participants and further refined through collective discussion.To guide the reader, we first describe the four thematic areas that emerged from the analysis of the interviews, which illustrate the role of food practices in promoting internal relationships, acting as operational and strategic tools, opening channels of interaction with the community and the territory, and contributing to the transformation of broader social representations, generating processes of recognition and empowerment. A summary of the main themes is presented in

Table 4.

We then present the ecological maps, created with staff members, which complement and expand on these themes by visually representing the organizational, relational, and territorial dynamics that shape the functioning of the social restaurant. A summary of the main themes is presented in

Table 5.

3.1.1. Food as a Central Feature of the Project: From Personal Experience to Social Interaction

The interviews reveal that food constitutes the symbolic and material center around which the entire identity of the project takes shape. The staff describe food as a vital aspect of community life, a space that fosters cohesion, shares narratives, and reinforces shared values. Food and food-related practices are described primarily as a language that connects different people and facilitates communication even in the absence of a common verbal code. As one of the workers observes: “Food is a relationship, a form of communication. We have found a way to communicate. Because there are so many different countries, and we don’t know each other’s languages. Instead, we talk without speaking the same language, but with food. Each woman has her own dish and talks about herself, about her identity (Int3)”. Or food is described as a language with customers who come from outside, as the dining room assistant explains: “When I talk about the Moroccan dish, I’m not just talking about myself, I’m talking about the Moroccan people and their culture. At the restaurant, I make sure that customers remember that it is not just about eating good, enjoyable food, but that it’s also something else entirely: food gives soul, it heals the soul. (Int4)”.

Food is deeply intertwined with the daily life of the project, strengthening the sense of belonging, as the coordinator points out: “Food is really what unites us all, at all times. Even I, who work in the office, arrive, taste something, and there is always the smell of something coming from the kitchen, because we work in the dining room right next to the kitchen. (Int1)” In addition to its informal dimension, food assumes a ritualized and formalized role in the training program. It is interesting to note that self-presentation through the creation of a meaningful dish constitutes one of the most intense moments of the entire program, as it explicitly links who participants are with what they produce, making food a concrete vehicle of identity expression, as the chef trainer explains: “Food is a bit like history. When we ask new trainees to introduce themselves, they come to this day called ‘Who am I?’ and introduce themselves by preparing a dish: this is a way of getting to know people, not the dish itself or the technique, but what it represents for that person. (Int8)” Furthermore, sharing food experiences can open spaces for dialogue on intimate or complex issues, as one interviewee explains: “Food is also a way to get to know each other better, to chat through food, and that has led us to talk about topics we wouldn’t have touched on if it hadn’t been for what we were cooking (…) During the pasta lesson, an intern was telling me about her husband, then we talked about my husband too; the other intern heard and joined in the conversation. So, yes, we got to know each other better starting from the pasta we were making, which led us to talk about cooking at home; something perhaps very simple, which may seem trivial, but which we might not have had the opportunity to talk about otherwise. (Int3)” The initial section underscores the way food assumes the roles of both an identity and a relational instrument within the project, thereby facilitating the establishment of interpersonal connections and fostering openness towards others.

3.1.2. Food as an Operational and Regulative Tool Within the Internal Community of the Project

In this second dimension, food and related practices are described as having an operational function within the project, through which group dynamics are regulated, critical issues are addressed, and strategies for coexistence are built, shaping the daily life of community work. In this sense, food acts as a third device: a material and symbolic tool that invites individuals to engage with each other, make decisions, manage differences, and define common ways of coexisting and collaborating. In the context of community work, a “third device” refers to an artefact, practice, or shared reference point that enables participants to engage with one another, regulate group dynamics, and co-construct common frameworks for collaboration. The first area in which this function manifests itself is the organization of work in the kitchen. Around daily food practices, shared rules are constructed, team-building strategies are tested, intercultural conflicts are addressed, and educational spaces are generated. The shared goal is to build a team: “Three people here and two people on the other side is not a team, it’s not what we want in the kitchen. You have to build a group. We work a lot with team building, with shared rules in the kitchen, with technical classes, with the chef, always together. (Int6)”.

Building a collaborative environment also involves addressing the challenges posed by cultural diversity, which can lead to misunderstandings in the kitchen: “Those who don’t know the language very well find it difficult to express themselves, and this makes things very difficult. (Int5).” In addition to interpersonal tensions, the challenges of shared work for the staff become visible and therefore addressable: “It helps us to be clear about our goal with respect to the program: we don’t have to make this space harmonious at all costs. We don’t have to become friends, but I have to point out that when you go to work, if you act this way, it comes back to you. The kitchen is a laboratory. (Int8)” This reflection represents a particularly powerful insight, as it emphasizes the importance of maintaining the collective goal of the project as a third general reference point, which goes beyond personal affinities or individual tensions. Thanks to reflections on food practices, it is thus possible to shift the focus from interpersonal dynamics to the shared goal of supporting the restaurant as a socially oriented space. Staff can thus articulate a process of constant accountability that helps regulate daily interactions and align different contributions toward a common mission.

The second theme that emerged relates to how food and food practices become operational strategies, formalized and continuously practiced by the team. A first strategy consists of creating informal moments of food sharing—such as lunches or free access to drinks and food—which reinforce the sense of welcome and community and open relational spaces even outside structured activities: “There is a benefit: free coffee, free water. (…) Lunch time, for example, after class, opens a moment of sharing that is also very important for those who did not participate in the class, where people from outside can also come. (Int2)” A second approach is the strategic use of the playful aspect of food. As the trainer chef explains, the humor and lightheartedness associated with cooking become tools for maintaining motivation: “My sous-chef and I create a playful atmosphere in the kitchen, because it’s better than silence… I mean, joking around helps a lot! You have to keep the mood up, because (the intern) is someone who woke up at 6 a.m., took four children to different schools, picked them up and then came here. (Int8)” A third strategic use of culinary practices is to use them as a means of dialogue and building shared knowledge: “(…) in the kitchen, while we’re doing the activity together, there’s a lot of dialogue, and even those who didn’t know how to cook churros, for example, now know how to make them, so the strength of the project is precisely the sharing, the exchange of knowledge and enriching each other and producing something new through collaboration: this is what you notice most in the kitchen. (Int4)” Finally, another strategic use is culinary storytelling as an intentional and collective practice. At the restaurant, every dish is an opportunity to give voice to individual and collective stories, to value the cultures of the participants’ origins and to make the training process visible, thereby turning food into a medium through which identities are expressed, negotiated, and shared. As one participant explains: “We have several meetings with the trainees and the head chef, where she gets inspiration to create this menu based on the trainees’ backgrounds; and this storytelling of cultures (through the dishes) is so central to the daily work that the whole team is involved in researching and creating these narratives. (Int1)” Every three months, the narratives of the dishes are constructed and refined during service: “there is this task: this is the menu, now build the narrative around it.’ (All this) reinforces these processes and each person becomes a bit of an ambassador for the narrative itself. (Int7)” Narratives also contributes to developing a decolonial approach, shifting the focus from technical performance to human experience and the valorization of the subjectivity of those who live in that community. In a context such as Italy, where food takes on a strong identity and normative value, the project works to deconstruct stereotypes and cultural hierarchies and “manages to create this dialogue starting from the story of the person; I don’t come to this restaurant because I want to taste the best Pakistani dish, but to support this woman who is committed to integrating herself and finding work. This is what the restaurant manages to do (Int4)”. The incorporation of food as a narrative strategy thus becomes a pivotal element, facilitating the convergence of values, educational, and community dimensions of the work experience through continuous operational reflection.

3.1.3. From Kitchen to City: Exploring and Transforming the Larger Community Through Food

A further level of analysis emerged from the interviews concerning the connection between the restaurant and the local area, both in terms of its integration into the urban fabric and its transformative function regarding the relationship between migration, citizenship, and community.

In this case, food functions as a catalyst for openness, exploration, and change. From an individual standpoint, employment at the restaurant has furnished the operators with novel insights into the urban milieu: “Here, we talk about lots of places; I discovered a restaurant, for example, which serves Chinese food, which is a bit unusual. Now I have a new map in my head of places that are interesting to try and discover. Much more than I had in my previous jobs. (Int2)” Working at the restaurant becomes an opportunity to rethink urban geography and forge new connections. One volunteer refers: “I was asked to go and buy something, I went to buy bread at the bakery, I’ve passed by a thousand times, I’d never noticed it. This has helped me a lot to be able to place things that I couldn’t place before. (Int3)” The relationships built up through the restaurant’s routine and physical proximity to other people in the area are also important: “We have this relationship with the bar opposite, or with the woman who cleans the library, who came in to ask for information for her sister who was arriving from the Ivory Coast. (Int2)” Finally, food facilitates conversation with outside customers. As the waitress observes: “Maybe… someone tastes something and then they’re curious (and ask), ‘Can you repeat the name, I want to make it at home, what was in it?’ It’s a kind of test, which becomes central to the conversation. (Int4)”.

Secondly, the words of the staff highlight the transformative potential that the project has for the wider community. The customer experience at the restaurant is not limited to the purely gastronomic dimension, but triggers deeper transformative processes, as one waitress explains: “When [a customer] comes to eat at the restaurant, they don’t just come for the food, but to try something they’ve never tried before. It has happened many times (that a dish was not liked), but then customers come back because they understand that they didn’t just come to eat. (Int8)” The culinary experience it offers become concrete references that can influence the representation of migrants, giving them humanity and dignity. The program director says: “Before, there was nothing about migrants in the press, they were almost invisible. Now there is, because at the restaurant this voice is strong, very present, very solid. So now I think people have a physical reference point. It’s a very psychological thing, this restaurant gives a lot of humanity, dignity, curiosity, beauty, it’s celebratory, it’s not sad, it’s a very positive voice. And this was absolutely not there before. (Int7)” Dialogue with the community on important issues is kept alive thanks to daily activities, as the director reports: “There is also co-working, which allows for continuous dialogue between the restaurant and the entire community. I see that people are talking more, and this is an important change because addressing this issue at the table [the phenomenon of migration] cannot be avoided, it is real, we are here, there is a huge community that needs to integrate. Integration is precisely communication between the two sides, it’s not, ‘I don’t eat pasta,’ you have to try it first. So, it’s important because it is the beginning of something. (Int7)” The restaurant therefore takes on value as a social device, promoting encounters and the construction of new shared frames of meaning.

3.1.4. Food as a Space for Agency: Practices of Self-Determination and Identity Transformation

The final theme emphasizes the transformative influence that culinary endeavors at the restaurant exert on a broader scale, functioning as a symbolic domain of agency and self-expression for the trainees.

The initial thematic cluster at this level pertains to the potential for individuals to reaffirm their sense of identity through the medium of food, thereby rediscovering the value of their own culture. The restaurant is a space that facilitates authentic expression: “We have a batter on the menu that in my culture is only made by high-class families. So, I’m proud because I celebrate birthdays with huge batters at the restaurant. I am proud of the food and tradition because before we just ate, we didn’t think about these things. Now with this restaurant, I think there is an origin and a story to tell. (Int4)” Finding oneself allows for a deeper change in one’s relationship with the social context: “I think that before I felt I had to become Italian in every way. I discovered while working here that this is completely a lie. I am very proud of the differences I bring to my work and to society. So yes, I have changed a lot… I have gone back to how I was before. I feel very much like myself, which is very nice. (Int7)”.

The second core principle emphasizes the empowerment of migrant women trainees participating in the project. The work undertaken at the restaurant has resulted in a shift in the perception of the kitchen as a space for invisible, privatized and unrecognized gender roles. Instead, it has become a setting for profound social recognition, even for those daily and ‘minor’ tasks that are reinterpreted as professional and cultural skills. This transformation in perception is indicative of a broader process of social change, whereby the social position of those involved is being redefined. The dining room manager employs an efficacious food metaphor to elucidate: “Before, when women told me about the food they cooked, it was worth nothing. But then they realized that the dishes they used to make back home, including everyday street foods, are actually great [valuable]! (Int5)” In addition, a former intern, now a restaurant manager, recounts how restaurant represented a space in which to give shape and direction to the practical knowledge she already possessed: “It gave me the right ideas. Because it came at a time when I was asking myself, ‘What am I doing here?’ and then I said to myself with this restaurant, ‘I can’t stop now.’ Here, I found a place to put the experience I had. (Int4)”.

Finally, the third thematic core highlights the power of cooking to enable the recognition of others as experts, subverting the hierarchies of knowledge typical of Western professionalization. The chef explains: “I follow the recipes, but if I am not sure, I ask how it’s done in your country: ‘Come and taste it, I want to know why you know better than me if the taste is the same!’. (Int6)” The intercultural cooking practices that are promoted and practiced at restaurant become deeply social and political symbolic devices. These devices have the power to promote new narratives about the value of differences and the transformative role of migrant culture in local society.

3.1.5. Ecological Maps

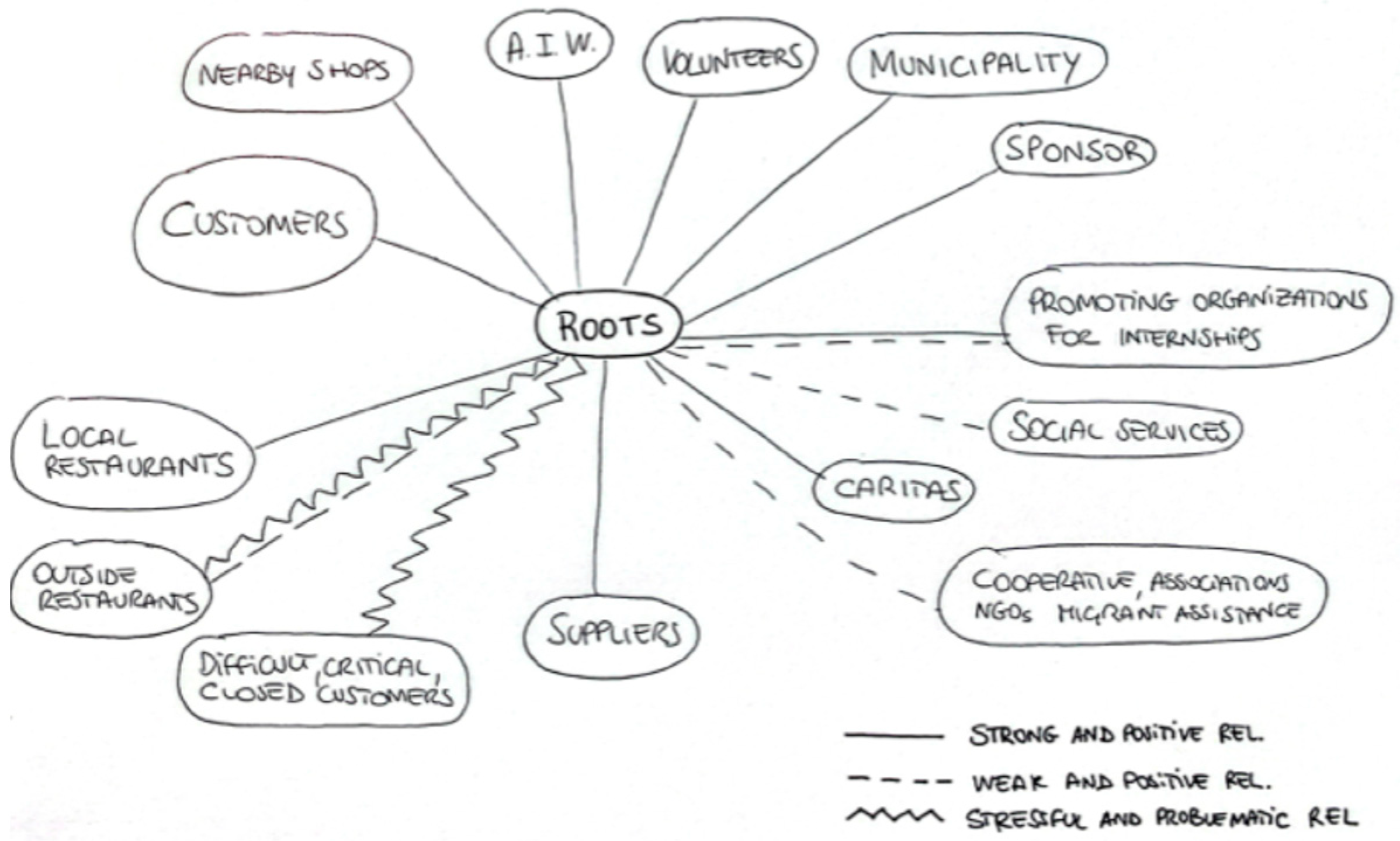

The ecological maps created after the interview by three key operators involved are presented together in

Figure 1. The maps highlight some significant convergences in how the social restaurant is perceived as positioned within the broader community fabric. What emerges is the image of a fluid and interconnected device, capable of operating as an interface between heterogeneous social subjects. Among the actors mentioned are organizations promoting internships and job placement, the regional government, the municipality, volunteers, sponsors, suppliers, local restaurants, customers, social services, and local associations. Concurrently, there have been reports of critical or problematic relationships with specific commercial entities, local associations, or customers who are perceived as rigid or unwelcoming.

3.2. Photo-Intervention Experience with Migrant Trainees

The second part of the results focuses on the photo-intervention process conducted with active trainees (t1) and former trainees (t2). To guide the reader through the analytical process, we present the thematic patterns that emerged separately within each group, and then highlight the points of continuity and change that allow us to understand how the meanings attributed to food evolved during the training experience. The main themes are summarized in

Table 6.

This section therefore complements the previous one by offering a visual and narrative overview of the personal and relational transformations associated with participation in the project. The thematic analysis revealed common themes between the two groups, both in terms of photo selection and final product. In addition, the analysis revealed variations in narrative style. These variations highlighted differences in terms of cohesion, experience, capacity for reflection, sense of community, and social responsibility.

One theme that emerged in both groups concerns the meaning of food as personal growth and future opportunities. Group t1 illustrated how shared food practices open new perspectives for the future. Personal growth, in the early stages of the training experience, takes on the meaning of humility, hard work, and patience “you have to know that we don’t know everything. We are discovering so many new things and humility is necessary and chef M. has a huge career, yet she comes here and talks to us as if we were friends. She teaches us with patience and humility (T1)” The narratives reveal that culinary learning requires a process of experimentation, error, and repetition, facilitated by teaching practices and a training environment based on respect and relationships in the kitchen. At the same time, personal growth is also articulated through happiness and a sense of self-efficacy derived from the awareness of having acquired new skills and achieved something independently. For group t2, the theme of personal growth also emerges clearly, albeit with a different nuance, linked to food practices such as transformation and rebirth.

Many of the women who have experienced migration, often characterized by feelings of loneliness, describe finding an opportunity for personal blossoming in their journey at the restaurant. In their narratives, food and food-related practices emerge as powerful agents of freedom to emerge from darkness, discover and rediscover oneself, as this former intern explains while showing her photos, visible in

Figure 2: “This is me alone, scared and with so many dreams of flying, of moving forward, but in our culture it is not possible for a woman to leave the house, work or have dreams. I am a moon that [used to] always be afraid of the sun. But not now, now I have [come out] during the day, I am the moon in the daytime (T2)”.

In this perspective, cooking represents for the participants (t2) not only technical support and satisfaction in creating a dish, as emphasized by the group of trainees (t1), but also an empowering experience and a stimulus for independence and social inclusion (e.g., obtaining a driver’s license, finding a job, or learning Italian). This interpretation enriches the value of patience with that of stability (not only economic), allowing personal and professional goals to be achieved. One of the women explains, “My dream was to become a chef, but now it is important for me to be independent, for my children. I want them to live in freedom—which I didn’t have before, but now I have a little bit. This is also this restaurant for me, this bicycle and the flowers: we are women, different, beautiful, independent, and here the restaurant has given us all beautiful things. (T2)”. In particular, the photographs of the former trainees (t2) provide a more comprehensive and retrospective view of their journey, accompanied by deep gratitude for the project and the opportunities offered by the shared practices.

The theme of food as a relational and cohesive space emerges in the group of trainees (t1), who describe how cooking together with other women has created a dynamic that goes beyond the common benefit of productivity, but which nourishes a feeling of connection, building a community made up of bonds between peers. This concept is expressed in a more complex way in group t2, which, in showing their photographs and commenting on those of others, demonstrates a level of emotional maturity and group cohesion, as well as a keen awareness of the theme of food-related relationships. The theme can be summarized as flourishing with and for each other: “flourishing with” because, through food and cooking, a dynamic of contact and knowledge is established with the other woman, like a “second family” that can nurture, grow, and become a source of support. One recognizes oneself in the other, receiving support and protection from woman to woman. The friendships formed during the journey are described and represented in the photographs as “a gift I received, the hand, the heart, the wonderful companions saved me. (T2)” And then “blooming for,” because once stability is achieved, women have the skills and maturity necessary to offer roots to other people, both to one’s own children and family, and to the next project interns and the women with they share the educational journey, as this former intern shows: “We are all here, dry [branches]. The water we take and give to the restaurant to grow… and [thus] we give roots to our children. We [also] work for the restaurant, we sacrifice ourselves by being ambassadors… (T2)”.

The metaphorical utilization of food as a medium for self-rediscovery can be linked to the metaphorical transformation of a tree, which is not only stable and anchored to the ground, but also serves as a source of nourishment for others to cultivate their own goals. The practice of sharing food is therefore outlined as a driving force of love, which, through the sharing of the culinary preparation, strengthens the sense of family, emotional, and community belonging. Activities in the kitchen, which frequently necessitate all participants to attend, are regarded as a drive for cohesion, enabling them to overcome feelings of isolation and offering a foundation for emancipation. This process fosters their uniqueness, encompassing both cultural and social dimensions, and facilitates the liberation from predefined social roles when needed.

This cultural aspect of food is best encapsulated by the theme of food as harmony and richness in differences, which emerged in the group of interns (t1). Around food, practices of sharing knowledge related to it are created, allowing everyone to express themselves in their diversity and, at the same time, to understand the richness of their differences. The cultural and knowledge exchange around food fosters a balance between the diverse backgrounds and experiences brought by the interns, as this woman explains while showing her photo (

Figure 3): “This represents the flavors we have on the menu: different, very tasty, many, but they go well together. Diversity, even if it sometimes seems strange, the different colors, create an unexpected perfection. I’ve tried flavors that I had no idea could go together, I found them here. (T1)”.

The opportunity to exchange ideas allows participants to understand that the priorities, meanings, and stories associated with food do not always match those of others. Food is the common thread running through all experiences, as is the identity of migrant women, which unites the participants not only in the present moment as a group, but also creates a continuity of identity over time, as new trainees join the program. The same theme is described in a similar way by group t2, which talks about food as a way of nourishing diversity and promoting dialogue. On the one hand, food emphasizes differences, promoting creativity and self-expression; on the other hand, it erases them, by placing everyone on the same level, overcoming cultural and personality barriers. As a former intern explains, showing a photo of a plate of couscous (see

Figure 4): “Food is not for the mouth, I realized that it is us, among ourselves… you from one place, me from another, even if we don’t know how to speak, here [food] brings you together, even if you don’t know how to speak their language or understand their character in the kitchen, you are in another world, you find many friends, we taste, we do things. For me, cooking is a way that unites everything (T2)”.

The last thematic block concerns the relationship with the community and cultures, both with respect to the country of origin and the local Italian territory. As far as the interns (t1) are concerned, the importance of food in feeling at home and meeting others emerges. The restaurant, in fact, on the one hand “makes you feel at home through hospitality and food, (T1)” but it is also “an opportunity to share your traditions. (T1)” The practices and narratives shared around food and the dishes on the menu play a fundamental role in shaping this meaning of food as a bridge between cultures, as this intern clearly illustrates: “it’s a responsibility on the one hand, we have to communicate to an audience that is not used to eating these things that it’s a beautiful and important thing. I always keep in mind… here they told us, ‘We don’t make traditional food, but food that allows us to talk between two cultures through food,’ which is different. Because traditionally they wouldn’t be like that… there’s the flexibility to say, ‘My dish has to speak to the other person, for a first encounter between two cultures.’ That’s what this restaurant means to me. (T1)” According to former interns (t2), this theme is expressed in different ways, in food as representation, integration, and responsibility. One former intern describes the sense of responsibility to pass on to customers and the local community what she has learned: “In food, we transform who we are, our character, taste, love… everything goes into this dish that we create and give to the customer. (T2)” In conclusion, it emerges that shared food practices generate a combination of new flavors thanks to the addition of Italian ingredients, in a metaphor for social inclusion: “In Tunisia, we don’t have Parmigiano Reggiano because it’s typical of Italy. When I added the Parmigiano, I mixed things up and created something new right here at the restaurant… it became a new dish because it has a special taste. (T2)”.

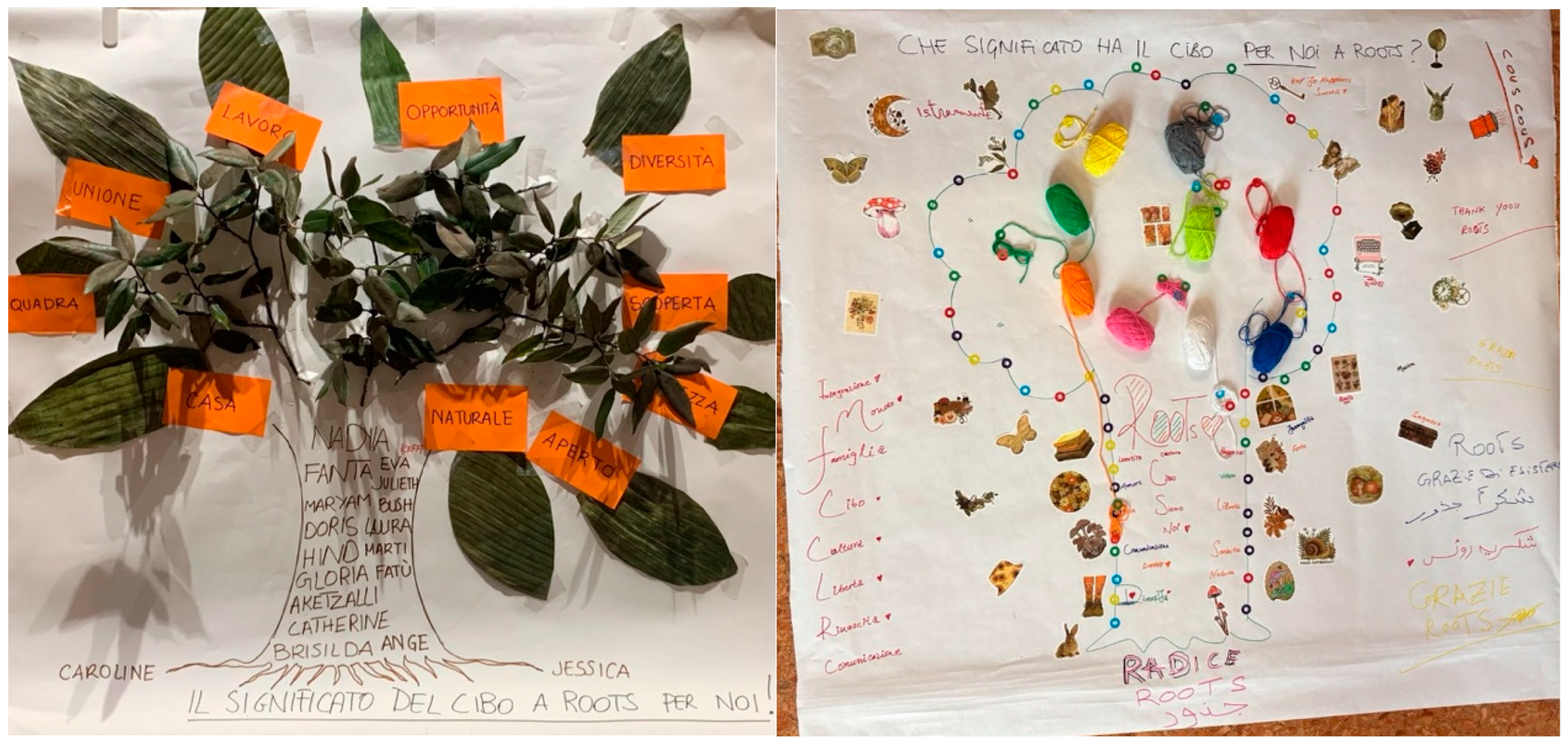

The final discussion within each group brought out visual narratives, which led to a very similar final material product between the two groups of participants, namely two representations of trees. The group of trainees (t1) describes their tree,

Figure 5, as unity and common roots in diversity: “We are all different, we have different dreams, we have different priorities, but there is always, for us women, there is always one thing that unites us. Like this tree, the leaves may be different, but the roots are always the same. (T1)” The tree of the former trainees (t2) shown in

Figure 5 echoes many of the keywords and suggestions of the previous group, but adds a nuance related to independence, a sense of family, and freedom: “Freedom and trust, the trust that this restaurant has given us through food; through food there are so many other things, integration, family. (T2)” The convergence on the tree metaphor in both groups suggests a deeper symbolic pattern beyond the similarity of the object. In psychosocial terms, the tree is a powerful metaphor for identity that is both grounded and evolving. It evokes a connection to one’s origins (roots), the nourishment and relational support that enable growth (trunk and branches), and an openness to future possibilities (new leaves and directions). The recurrence of this image in two independent groups suggests that participants collectively interpret their experience in the project as a simultaneous process of rooting, expansion, and transformation. The tree becomes a shared, representative materiality articulating the dual movement of migrant identities, which are anchored in personal and cultural histories yet dynamically reshaped by interactions, practices, and opportunities encountered.

3.3. World Café and Participatory Affective Cartography

The third and final section of the results focuses on the collective activities carried out during the World Café and the participatory affective mapping session, as illustrated in

Figure 6. To ensure continuity with the previous analytical phases, this section explores how the themes identified at the individual and group levels translate into broader reflections on urban spaces, dining venues, and community cohesion. We first present the thematic insights that emerged from the discussion tables, then illustrate how these contributions were visually synthesized through the map. The main discussion themes that emerged are presented in

Table 7.

The first discussion theme sought to define the characteristics of a place that nurtures in an urban context. A nurturing place was described as a space that supports, welcomes, and allows people to feel recognized, promoting self-construction and the formation of meaningful bonds. These reflections highlight that the concept of a welcoming place is associated with its relational, symbolic, and experiential potential. These are places where it is possible to “feel recognized” which refers to a deeper psychosocial process: the possibility of being seen as legitimate subjects within the urban fabric. However, obstacles were also identified that limit access to such spaces for the women participants: language barriers, relational insecurities, perceived mistrust on the part of local citizens, and a lack of knowledge of the urban area. These aspects underscore how access to urban spaces is also mediated by social representations and power relations. The restaurant was spontaneously cited as a concrete example of a public place that offers opportunities for exchange, thanks to its welcoming atmosphere and daily practices that value the culture of the participants.

The second theme focused on which spaces promote the reception and inclusion of migrants, with particular reference to the analyzed context. The discussion revealed a connection between urban accessibility, language barriers, and the actual possibility of feeling welcome. Large supermarkets are perceived as less demanding in terms of interaction and more linguistically safe: “I go to the supermarket because I don’t know the city. I don’t go out if I’m a migrant woman. And at the supermarket, I don’t have to talk to anyone.” These reflections highlight how the experience of inclusion in the city is mediated more by the social conditions that make these spaces navigable. The preference for supermarkets as linguistically safe contexts highlights how the fear of miscommunication shapes daily mobility, also producing subtle forms of self-isolation. The city market was then cited as one of the few places capable of fostering informal intercultural exchange. This also suggests that inclusion emerges where interaction is possible in everyday exchanges. Experiences of socialization linked to events promoted by associations or convivial moments within specific projects also emerged, including the restaurant, defined as “an exception.” However, these experiences are still fragmented, little known, and difficult to access except through informal networks. This fact points to the need for intentional, community-oriented infrastructure that actively reduces barriers to participation.

The third table worked on the theme of how food places can help build bonds in the community. The discussion highlighted differences between long-term residents and more recent migrant arrivals. Two types of places emerged: on the one hand, spaces evocative of family memories (such as pasta shops frequented by grandmothers or mothers); on the other, places run by women as examples of female representation in the food industry. For long-time residents, places linked to food and family memories evoke continuity and intergenerational belonging, reinforcing a stable sense of belonging to the place. For more recent migrants, however, food-related places run by women become reference points through which to imagine new possibilities. Institutional spaces, such as schools and parishes, were also mentioned, which promote socialization and intercultural openness through food.

Overall, the discussion provided a critical and proactive vision of the city, highlighting the need to rethink food places as meeting places, as social arenas where relationships are established, identities are negotiated, and forms of everyday citizenship take shape. Food venues emerge as micro-infrastructures of urban life capable of challenging isolation, redistributing opportunities for participation, and enabling encounters that might not otherwise take place. Rethinking these spaces as meeting points therefore means recognizing their potential to reshape the affective and relational geography of the city, transforming them into accessible, inclusive, and culturally significant environments where differences can coexist, be recognized, and create new possibilities for community building.

Based on the content that emerged from the three round tables, the group co-constructed an affective map of food places in the city, shown in

Figure 7.

The map facilitated a visual summary of the experience and an exchange of localized knowledge, also allowing participants to discover previously unknown spaces. Significantly, the restaurant was represented with the word “rebirth,” signaling the transformative value attributed to the place and the experiences lived within it. Beyond its descriptive function, the map served as a psychosocial instrument that materialized the collective meaning attributed to the city by the group. Participants reconfigured the geography of the city by placing emotions, memories, and relational experiences in the urban landscape. They identified the places they frequent and those where they feel they belong. The affective map is a conceptual framework that captures and reinterprets the dynamics of urban space, emphasizing the active role of migrant women in reshaping the urban environment. By ascribing significance, sense of security, and a sense of possibility to specific locations, these women contribute to the creation of a new urban topography. It functions also as a cartography of possibilities, illuminating the conditions under which relationships can flourish, identities can be cultivated, and experiences that have been marginalized can be recognized and made visible.

Taken together, the methods used in this study offer a comprehensive picture of how food practices operate as relational, symbolic, and transformative tools. The interviews highlight the daily organizational and interpersonal dynamics through which food promotes internal cohesion, operational efficiency, and community involvement. The ecological maps visually reinforce these findings by placing the restaurant within a broad network of actors, highlighting its role in the urban fabric. The photointervention adds an experiential dimension of the trainees to the analysis, revealing how participation in the project contributes, through food, to building the women’s identity, strengthening their capacity to act, and generating new forms of mutual support. Finally, the World Café and the participatory affective map extend this analysis to citizenship, showing how other food venues can also contribute to generating a sense of belonging, facilitating encounters between different people, and reconfiguring perceptions of accessibility and inclusion. A consistent pattern emerges across all methods: food simultaneously serves as a language, a resource, and a catalyst for individual and collective transformation.