Hope into Achievement: A Longitudinal Examination of Hope, Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement in a Sample of High School Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hope

3. Hope and Academic Achievement

4. School-Related Psychosocial Perceptions

5. Psychosocial Perceptions and Academic Achievement

6. Hope, School-Related Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement

7. The Current Study

8. Method

8.1. Participants and Procedure

8.2. Measures

8.2.1. Hope

8.2.2. Academic Self-Concept

8.2.3. Self-Efficacy

8.2.4. Academic Motivation

8.2.5. Goal Valuation

8.2.6. Grade Point Average

9. Results

9.1. Preliminary Analyses

9.2. How Hope and School-Related Psychosocial Perceptions Relate to Academic Achievement Over Time

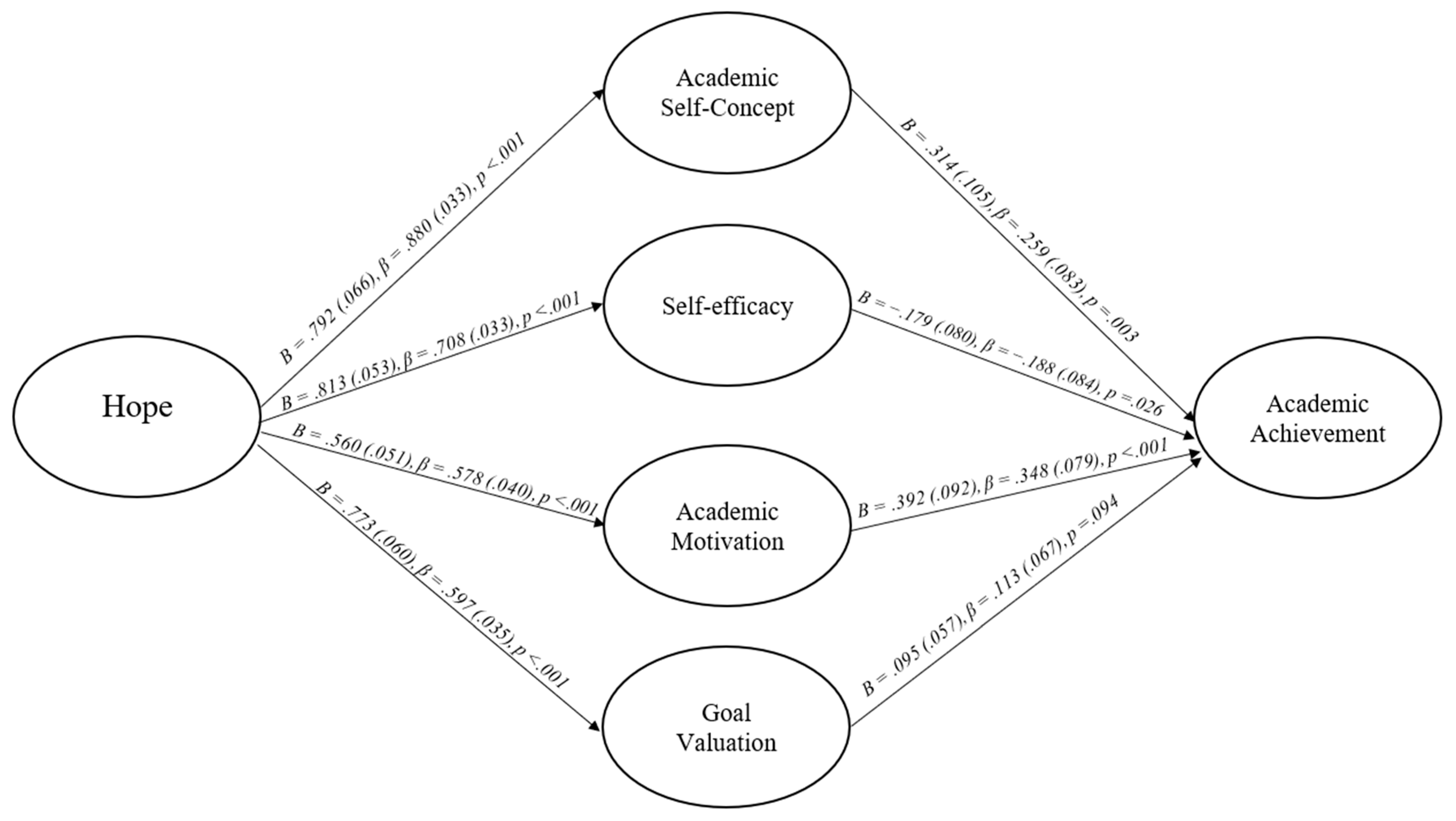

9.3. Hope into Achievement Theory Model

10. Discussion

10.1. Study Implications

10.2. Limitations

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd-El-Fattah, S., & Patrick, R. (2011). The relationship among achievement motivation orientations, achievement goals, and academic achievement and interest: A multiple mediation analysis. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 11, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M. A., & Dahling, J. J. (2016). Learning goal orientation and locus of control interact to predict academic self-concept and academic performance in college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. (2016). Relationship between sense of rejection, academic achievement, academic efficacy, and educational purpose in high school students. Education and Science, 41, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik, G., & Erkan Atik, Z. (2017). Predicting hope levels of high school students: The role of academic self-efficacy and problem solving. Education and Science, 42, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., & Giammarco, E. A. (2015). Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, A., Tokalic, R., Amílcar Silva Cunha, J., Novak, I., Suto, J., Vidak, M., Miosic, I., Vuka, I., Poklepovic Pericic, T., & Puljak, L. (2019). Assessments of attrition bias in Cochrane systematic reviews are highly inconsistent and thus hindering trial comparability. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkıs, M., Arslan, G., & Duru, E. (2016). The school absenteeism among high school students: Contributing factors. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(6), 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Taştan, S., Davoudi, S. M., Masalimova, A. R., Bersanov, A. S., Kurbanov, R. A., Boiarchuk, A. V., & Pavlushin, A. A. (2018). The impacts of teacher’s efficacy and motivation on student’s academic achievement in science education among secondary and high school students. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(6), 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendes, D., Keefe, F. J., Somers, T. J., Kothadia, S. M., Porter, L. S., & Cheavens, J. S. (2010). Hope in the context of lung cancer: Relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 40(2), 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoms, G., & Schmidt-Davis, J. (2010). The three essentials: Improving schools requires district vision, district and state support, and principal leadership. Southern Regional Education Board. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Wood, R., Unsworth, K., Hattie, J., Gordon, L., & Bower, J. (2009). Self-efficacy and academic achievement in Australian high school students: The mediating effects of academic aspirations and delinquency. Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheavens, J. S., Michael, S. T., & Snyder, C. R. (2005). The correlates of hopeful thought: Psychological and physiological benefits. In J. Elliott (Ed.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on hope (pp. 119–132). NovaScience. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Huebner, E. S., & Tian, L. (2020). Longitudinal relations between hope and academic achievement in elementary school students: Behavioral engagement as a mediator. Learning and Individual Differences, 78, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delas, Y., Lafreničre, M.-A. K., Fenouillet, F., Paquet, Y., & Martin-Krumm, C. (2017). Hope, perceived ability, and achievement in physical education classes and sports. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 17(1), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickhäuser, O., Dinger, F. C., Janke, S., Spinath, B., & Steinmayr, R. (2016). A prospective correlational analysis of achievement goals as mediating constructs linking distal motivational dispositions to intrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2017). Hope across achievement: Examining psychometric properties of the Children’s Hope Scale across the range of achievement. SAGE Open, 2017(7), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2019a). Hope into action: How clusters of hope relate to success-oriented behavior in school. Psychology in the Schools, 56(9), 1493–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2019b). Incorporating hope and positivity into educational policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2019c). Is grit worth the investment? How grit compares to other psychosocial factors in predicting achievement. Current Psychology, 40(7), 3166–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2023). Promoting hope in minoritized and economically disadvantaged students. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., & Gentzis, E.-A. (2023). To hope and belong in adolescence: A potential pathway to increased academic engagement for African American Males. School Psychology Review, 52(3), 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., Jansen, L., Gentzis, E.-A., & Worrell, F. C. (2024). Gifted profiles of hope: Being hopeful is associated with a talent development psychosocial profile in gifted students. High Ability Studies, 35(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., Keltner, D., Worrell, F. C., & Mello, Z. (2017a). The magic of hope: Hope mediates the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., & Stevens, D. (2018). A potential avenue for academic success: Hope predicts an achievement-oriented psychosocial profile in African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(6), 532–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., Worrell, F. C., & Mello, Z. (2017b). Profiles of hope: How clusters of hope relate to school variables. Learning and Individual Differences, 59, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., Worrell, F. C., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Subotnik, R. F. (2016). Beyond perceived ability: The contribution of psychosocial factors to academic performance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1377(1), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkman, F., Caner, A., Sart, Z. H., Börkan, B., & Şahan, K. (2010). Influence of perceived teacher acceptance, self-concept, and school attitude on the academic achievement of school-age children in Turkey. Cross-Cultural Research, 44(3), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D. B., & Dreher, D. E. (2012). Can hope be changed in 90 minutes? Testing the efficacy of a single-session goal-pursuit intervention for college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(4), 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D. B., & Kubota, M. (2015). Hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and academic achievement: Distinguishing constructs and levels of specificity in predicting college grade-point average. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenzel, L. M., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2007, April 12). Educating at-risk urban African American children: The effects of school climate on motivation and academic achievement [Paper presentation]. American Educational Research Association Conference 2017, Chicago, IL, USA. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497443.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Fernández, A. R., Droguett, L., & Revuelta, L. R. (2012). School and personal adjustment in adolescence: The role of academic self-concept and perceived social support. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 17(2), 397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, C. J., Davis, C. W., Kim, Y., Kim, Y. W., Marriott, L., & Kim, S. (2017). Psychosocial factors and community college Student Success: A meta-analytic investigation. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 388–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2017). The Oxford handbook of hope. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M. W., Marques, S. C., & Lopez, S. J. (2017). Hope and the academic trajectory of college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzis, E.-A., & Dixson, D. D. (2024). How school climate relates to other psychosocial perceptions and academic achievement across the school year. School Psychology Review, 53(5), 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F., Ratelle, C. F., Roy, A., & Litalien, D. (2010). Academic self-concept, autonomous academic motivation, and academic achievement: Mediating and additive effects. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(6), 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2018, December). Hattie ranking: 252 influences and effect sizes related to student achievement. Available online: https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement/ (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Hornstra, L., van der Veen, I., Peetsma, T., & Volman, M. (2013). Developments in motivation and achievement during primary school: A longitudinal study on group-specific differences. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, L. M., Snyder, C. R., & Crowson, J. J., Jr. (1998). Hope and coping with cancer by college women. Journal of Personality, 66(2), 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A. (2024, October 6). Measuring model fit. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2014). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Ganotice, F. A. (2014). The social underpinnings of motivation and achievement: Investigating the role of parents, teachers, and peers on academic outcomes. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., Karau, S. J., & Schmeck, R. R. (2009). Role of the big five personality traits in predicting college students’ academic motivation and achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., & Nadler, D. (2013). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: Why do implicit beliefs, goals, and effort regulation matter? Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. S., & Jang, H. Y. (2018). The roles of growth mindset and grit in relation to hope and self-directed learning. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society, 9(1), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaletta, P. R., & Oliver, J. M. (1999). The hope construct, will, and ways: Their relations with self-efficacy, optimism, and general well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C., Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2017). Hope- and academic-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 9(3), 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C., Lopez, S. J., Fontaine, A. M., Coimbra, S., & Mitchell, J. (2015). How much hope is enough? Levels of hope and students’ psychological and school functioning. Psychology in the Schools, 52(4), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C., Lopez, S. J., & Mitchell, J. (2013). The role of hope, spirituality and religious practice in adolescents’ life satisfaction: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C., Lopez, S. J., & Pais-Ribeiro, J. L. (2011a). “Building hope for the future”: A program to foster strengths in middle-school students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C., Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2011b). The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(6), 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(3), 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & O’Mara, A. (2008). Reciprocal effects between academic self-concept, self-esteem, achievement, and attainment over seven adolescent years: Unidimensional and multidimensional perspectives of self-concept. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(4), 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Steinbeck, K. (2017). The role of puberty in students’ academic motivation and achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 53, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoach, D. B., & Siegle, D. (2003). The School Attitude Assessment Survey-Revised: A new instrument to identify academically able students who underachieve. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(3), 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Mplus user’s guide. Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Ommundsen, Y., Haugen, R., & Lund, T. (2005). Academic self-concept, implicit theories of ability, and self-regulation strategies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(5), 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F., & Graham, L. (1999). Self-efficacy, motivation constructs, and mathematics performance of entering middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24(2), 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Watson, B., López, B., Ojeda, L., & Rodriguez, K. M. (2015). Cultural and cognitive predictors of academic motivation among Mexican American adolescents: Caution against discounting the impact of cultural processes. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 43(2), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K. L., Martin, A. D., & Shea, A. M. (2011). Hope, but not optimism, predicts academic performance of law students beyond previous academic achievement. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(6), 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K. L., Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C., & Fortney, S. K. (2020). Hope and optimism as predictors of academic performance and subjective well-being in college students. Learning and Individual Differences, 81, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, T. L., & Chenier, J. S. (2016). Further validation of the student subjective wellbeing questionnaire: Comparing first-order and second-order factor effects on actual school outcomes. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36(4), 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W. M., Ramirez, M. P., Magriña, A., & Allen, J. E. (1980). Initial development and validation of the Academic Self-Concept scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 40(4), 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C., & Rand, K. L. (2020). Hope, optimism, and affect as predictors and consequences of expectancies: The potential moderating roles of perceived control and success. Journal of Research in Personality, 84, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Valås, H. (1999). Relations among achievement, self-concept, and motivation in mathematics and language arts: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 67(2), 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., Highberger, L., Ribinstein, H., & Stahl, K. J. (1997). The development and validation of the children’s hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams, V. H., III, & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S. M., Shaffer, E. J., & Shaunessy, E. (2007). An independent investigation of the validity of the school attitude assessment survey-revised. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 26(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M. F., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2004). Further evaluation of the children’s hope scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 22, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, M. J., Gravely, A. A., & Roseth, C. J. (2009). Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M. W. (2018). Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(3), 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, R., & Speridakos, E. C. (2011). A meta-analysis of hope enhancement strategies in clinical and community settings. Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice, 1(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | α (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hope_T1 | – | 3.74 | 0.67 | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) | |||||

| 2. Academic Self-Concept_T2 | 0.39 | – | 4.27 | 0.67 | 0.66 (0.61–0.71) | ||||

| 3. Self-Eficacy_T2 | 0.51 | 0.65 | – | 3.79 | 0.64 | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | |||

| 4. Academic Motivation_T2 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.62 | – | 3.69 | 0.67 | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) | ||

| 5. Goal Valuation_T2 | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.57 | – | 4.43 | 0.62 | 0.90 (0.88–0.91) | |

| 6. Grade Point Average_T3 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.40 | – | 3.45 | 0.72 | 0.90 (0.88–0.91) |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | (90% C.I.) | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Models | |||||||

| Hope_T1 | 32.53 * | 9 | 0.988 | 0.979 | 0.070 | (0.045, 0.097) | 0.56–0.83 |

| Academic Self-Concept_T2 | 16.84 * | 2 | 0.984 | 0.951 | 0.118 | (0.071, 0.173) | 0.50–0.80 |

| Self-Efficacy_T2 | 135.35 * | 20 | 0.976 | 0.967 | 0.104 | (0.088, 0.121) | 0.64–0.80 |

| Academic Motivation_T2 | 173.40 * | 27 | 0.970 | 0.960 | 0.101 | (0.087, 0.116) | 0.49–0.81 |

| Goal Valuation_T2 | 43.50 * | 9 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.085 | (0.061, 0.111) | 0.80–0.89 |

| Theorized Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Model 1) | |||||||

| Hope-Psychosocial Perceptions-Achievement | 1978.84 * | 515 | 0.915 | 0.907 | 0.073 | (0.070, 0.077) | |

| Hope_T1 | 0.52–0.67 | ||||||

| Academic Self-Concept_T2 | 0.60–0.79 | ||||||

| Self-Efficacy_T2 | 0.66–0.80 | ||||||

| Academic Motivation_T2 | 0.54–0.80 | ||||||

| Goal Valuation_T2 | 0.79–0.90 | ||||||

| Theorized Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Minus Goal Valuation; Model 2) | |||||||

| Hope-Psychosocial Perceptions-Achievement | 1065.79 * | 342 | 0.943 | 0.937 | 0.063 | (0.059, 0.067) | |

| Hope_T1 | 0.61–0.78 | ||||||

| Academic Self-Concept_T2 | 0.61–0.78 | ||||||

| Self-Efficacy_T2 | 0.66–0.80 | ||||||

| Academic Motivation_T2 | 0.56–0.81 | ||||||

| Theorized Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Minus Goal Valuation and Self-Efficacy, Model 3) | |||||||

| Hope-Psychosocial Perceptions-Achievement | 528.64 * | 166 | 0.952 | 0.945 | 0.064 | (0.058, 0.070) | |

| Hope_T1 | 0.59–0.79 | ||||||

| Academic Self-Concept_T2 | 0.59–0.79 | ||||||

| Academic Motivation_T2 | 0.52–0.79 | ||||||

| Path | b | S.E. | β | S.E. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Model 1) | |||||

| Total Indirect | 0.396 | 0.047 | 0.364 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Self-Concept_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.249 | 0.082 | 0.228 | 0.075 | 0.002 |

| Hope_T1—Self-efficacy_T2—GPA_T3 | −0.145 | 0.065 | −0.133 | 0.059 | 0.024 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Motivation_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.220 | 0.056 | 0.201 | 0.050 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1— Goal Valuation_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.073 | 0.045 | 0.067 | 0.041 | 0.098 |

| Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Without Goal Valuation, Model 2) | |||||

| Total Indirect | 0.222 | 0.034 | 0.236 | 0.033 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Self-Concept_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.222 | 0.060 | 0.237 | 0.062 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1—Self-efficacy_T2—GPA_T3 | −0.158 | 0.053 | −0.169 | 0.055 | 0.003 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Motivation_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.157 | 0.037 | 0.168 | 0.038 | <0.001 |

| Hope into Achievement Theory Model (Without Goal Valuation and Self-Efficacy, Model 3) | |||||

| Total Indirect | 0.254 | 0.031 | 0.276 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Self-Concept_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.136 | 0.039 | 0.148 | 0.041 | <0.001 |

| Hope_T1—Academic Motivation_T2—GPA_T3 | 0.118 | 0.034 | 0.128 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dixson, D.D.; Gentzis, E.-A.; Jansen, L.; Whitley, K. Hope into Achievement: A Longitudinal Examination of Hope, Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement in a Sample of High School Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121657

Dixson DD, Gentzis E-A, Jansen L, Whitley K. Hope into Achievement: A Longitudinal Examination of Hope, Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement in a Sample of High School Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121657

Chicago/Turabian StyleDixson, Dante D., Ersie-Anastasia Gentzis, Leah Jansen, and Kayla Whitley. 2025. "Hope into Achievement: A Longitudinal Examination of Hope, Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement in a Sample of High School Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121657

APA StyleDixson, D. D., Gentzis, E.-A., Jansen, L., & Whitley, K. (2025). Hope into Achievement: A Longitudinal Examination of Hope, Psychosocial Perceptions, and Academic Achievement in a Sample of High School Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121657