The Effects of Behavioral Relaxation Training on Academic Task Completion Among Students with Autism in Inclusive Classrooms: A Single-Subject Design Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Academic Performance and Academic Anxiety

1.2. Behavioral Relaxation Treatment (BRT)

Head-supported by the chair cushion and straight with respect to body midline; eyes-lids closed smoothly and no motion of eyes beneath them; mouth-lips and teeth slightly parted; throat-motionless (i.e., no swallowing); shoulders-rounded, transecting the same horizontal plane, motionless; body-torso, hips, and legs symmetrical around midline, motionless; hands-resting on chair armrest or on thighs, palms down with fingers slightly curled; feet-heels on chair footrest with toes pointing in a V; quiet1-no vocalizations or loud respiratory sounds; breathing-slow and regular.

1.3. The Present Study

- Do students with autism demonstrate increased relaxation following BRT?

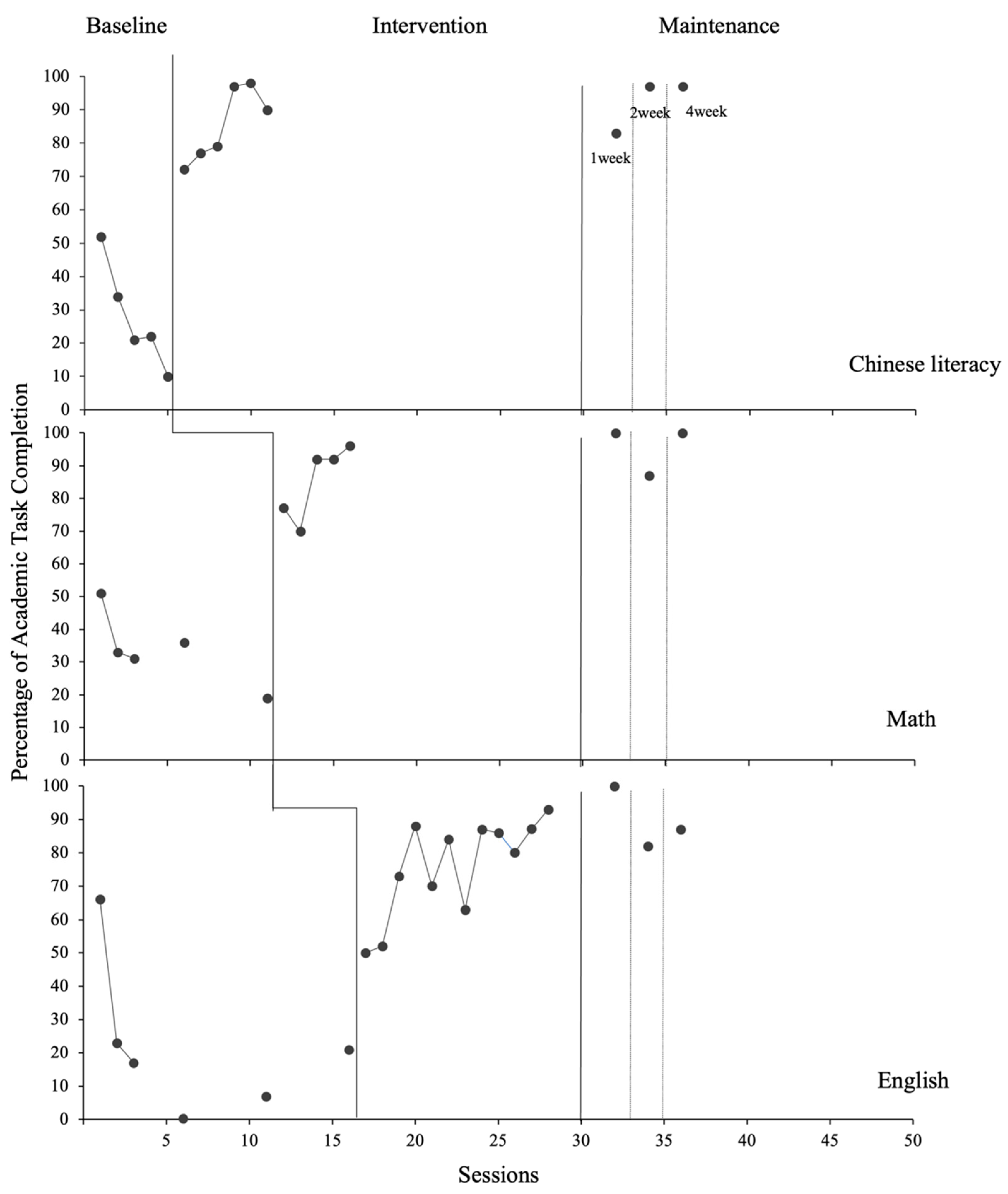

- Does task completion in the three core subjects (Chinese literacy, mathematics, and English) improve after students with autism receive BRT?

- Are improvements in task completion maintained after the intervention ends?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Setting

2.3. Research Team

2.4. Research Design

2.5. Intervention Materials

2.6. Dependent Variables and Measurement

2.6.1. Primary Dependent Variable

2.6.2. Secondary Dependent Variables

2.7. Experimental Arrangements and Procedures

2.7.1. Pre-Intervention Probes

2.7.2. Baseline

2.7.3. Prerequisite Skill Training

Body Part Tacting

Individual Relaxation Behavior Learning

Integrated Behavior Skills Training

2.7.4. Intervention

2.7.5. Post-Intervention Probes

2.7.6. Maintenance

2.8. Procedural Fidelity

2.9. Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

2.10. Social Validity

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral and Physiological Relaxation

3.1.1. Bob

3.1.2. Sam

3.2. Academic Task Completion

3.2.1. Bob

3.2.2. Sam

4. Discussion

4.1. Why BRT Works for Students with Autism

4.2. Why BRT Can Support Academic Performance in Students with Autism

4.3. Limitation

4.4. Implications for Future Research and Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the following content, we adopted the term “quiet” as used by Lundervold et al. (2020) to describe one of the target relaxed behaviors, although it appears to refer more to a state of action or behavior rather than a discrete behavior itself. |

References

- Ambler, P. G., Eidels, A., & Gregory, C. (2015). Anxiety and aggression in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders attending mainstream schools. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 18, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y. S., Chiang, H.-M., & Hickson, L. (2015). Mathematical word problem solving ability of children with autism spectrum disorder and their typically developing peers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2200–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baixauli, I., Rosello, B., Berenguer, C., Téllez De Meneses, M., & Miranda, A. (2021). Reading and writing skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 646849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. E. H., & Cleary, S. (2015). Review of evidence-based mathematics interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 50(2), 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtler, J. (2011). Reduction of anxiety in college students with Asperger’s disorder using behavioral relaxation training [Master’s thesis, Rowan University]. Available online: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/82 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Blanchard, E. B., & Andrasik, F. (1985). Management of chronic headaches: A psychological approach (pp. xi, 203). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, L. B., & Mueller, R. J. (1986). An instrument for the assessment of study behaviors of college students. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED268180 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bossenbroek, R., Wols, A., Weerdmeester, J., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Granic, I., & van Rooij, M. M. (2020). Efficacy of a virtual reality biofeedback game (DEEP) to reduce anxiety and disruptive classroom behavior: Single-case study. JMIR Mental Health, 7(3), e16066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L. E., Waslin, S. M., Gastelle, M., Kochendorfer, L. B., & Kerns, K. A. (2023). Anxiety, academic achievement, and academic self-concept: Meta-analytic syntheses of their relations across developmental periods. Development and Psychopathology, 35(4), 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullen, J. C., Swain Lerro, L., Zajic, M., McIntyre, N., & Mundy, P. (2020). A developmental study of mathematics in children with autism spectrum disorder, symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4463–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarotti, F., & Venerosi, A. (2020). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders: A review of worldwide prevalence estimates since 2014. Brain Sciences, 10(5), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. D., Brown, C. L., Smarinsky, E. C., Popejoy, E. K., & Boykin, A. A. (2024). Reducing student anxiety using neurofeedback-assisted mindfulness: A quasi-experimental single-case design. Journal of Counseling and Development, 102(3), 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, J. T., & Wood, J. J. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy for children with autism: Review and considerations for future research. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 34(9), 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lijster, J. M., Dieleman, G. C., Utens, E. M., van der Ende, J., Alexander, T. M., Boon, A., Hillegers, M. H., & Legerstee, J. S. (2019). Online attention bias modification in combination with cognitive-behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: A randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Change, 36(4), 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowker, A. (2020). Arithmetic in developmental cognitive disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 107, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eufemia, R. L., & Wesolowski, M. D. (1983). The use of a new relaxation method in a case of tension headache. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 14(4), 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, E., & Mazin, A. L. (2016). Strategies for increasing reading comprehension skills in students with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 39(2), 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevarter, C., Bryant, D. P., Bryant, B., Watkins, L., Zamora, C., & Sammarco, N. (2016). Mathematics interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(3), 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercio, J. M., Ferguson, K. E., & McMorrow, M. J. (2001). Increasing functional communication through relaxation training and neuromuscular feedback. Brain Injury, 15(12), 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvert, E., Davidson, D., & Scott, C. M. (2019). An in-depth analysis of expository writing in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(8), 3412–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, R. D., & Baer, D. M. (1978). Multiple-probe technique: A variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(1), 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, M. A., & Ollendick, T. H. (2012). Treatment of comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and anxiety in children: A multiple baseline design analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(2), 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman, V., Krishnan Vijayalakshmi, R. A., & Partheeban, P. (2024). Physiological impact of test anxiety on student’s academic performance using convolution neural network. Journal of Computational Analysis and Applications (JoCAAA), 33(7), 886–904. Available online: https://eudoxuspress.com/index.php/pub/article/view/1152 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Juncos, D. G., & Markman, E. J. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: A single subject design with a university student. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S. A., Lemons, C. J., & Davidson, K. A. (2016). Math interventions for students with autism spectrum disorder: A best-evidence synthesis. Exceptional Children, 82(4), 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, R. L., Openden, D., & Koegel, L. K. (2004). A systematic desensitization paradigm to treat hypersensitivity to auditory stimuli in children with autism in family contexts. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29(2), 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R., Regester, A., Lauderdale, S., Ashbaugh, K., & Haring, A. (2010). Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behaviour therapy: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Pentz, T. G. (2015). The teaching interaction procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, P. M., Woolfolk, R. L., & Sime, W. E. (2007). Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, W. R., & Baty, F. J. (1986). Behavioural relaxation training: Explorations with adults who are mentally handicapped. Journal of the British Institute of Mental Handicap (APEX), 14(4), 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Mao, Y., Lory, C., Lei, Q., & Zeng, Y. (2024). The effect of computation interventions for students with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 61(10), 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundervold, D. A., Poppen, R., & Guercio, J. M. (2020). Behavioral relaxation training: Clinical applications with diverse populations (3rd ed.). Sloan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy, S. M., Silva, G. E., Kaemingk, K. L., Goodwin, J. L., & Quan, S. F. (2010). Cognitive functioning and academic performance in elementary school children with anxious/depressed and withdrawn symptoms. The Open Pediatric Medicine Journal, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, C., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2017). The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: A multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism and Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 2396941516684834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S., Roisman, G. I., Long, J. D., Burt, K. B., Obradović, J., Riley, J. R., Boelcke-Stennes, K., & Tellegen, A. (2005). Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, S. L., & Pinkelman, S. E. (2020). Improving on-task behavior in middle school students with disabilities using activity schedules. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(1), 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, B. H., Scozzafava, M. D., Bradley, T., Matlow, R., Weems, C. F., & Carrion, V. G. (2023). Impact of anxiety and depression on academic achievement among underserved school children: Evidence of suppressor effects. Current Psychology, 42(30), 26793–26801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michultka, D. M., Poppen, R. L., & Blanchard, E. B. (1988). Relaxation training as a treatment for chronic headaches in an individual having severe developmental disabilities. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 13(3), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L. E., Burke, J. D., Troyb, E., Knoch, K., Herlihy, L. E., & Fein, D. A. (2017). Preschool predictors of school-age academic achievement in autism spectrum disorder. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 31(2), 382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moilanen, K. L., Shaw, D. S., & Maxwell, K. L. (2010). Developmental cascades: Externalizing, internalizing, and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbury, C., & Nation, K. (2011). Understanding variability in reading comprehension in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Interactions with language status and decoding skill. Scientific Studies of Reading, 15(3), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuske, H. J., McGhee Hassrick, E., Bronstein, B., Hauptman, L., Aponte, C., Levato, L., Stahmer, A., Mandell, D. S., Mundy, P., Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2019). Broken bridges-new school transitions for students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review on difficulties and strategies for success. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(2), 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, E. L., Ainsworth, B., Chadwick, P., & Atkinson, M. J. (2023). The role of emotion regulation in the relationship between mindfulness and risk factors for disordered eating: A longitudinal mediation analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(2), 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paclawskyj, T. R. (2011). Behavioral relaxation training (BRT) for persons who have intellectual disability. In Psychotherapy for individuals with intellectual disability (pp. 107–129). NADD Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perihan, C., Bicer, A., & Bocanegra, J. (2022). Assessment and treatment of anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder in school settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14(1), 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppen, R. (1998). Behavioral relaxation training and assessment (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Price, E., Lau, A. C., Goldberg, F., Turpen, C., Smith, P. S., Dancy, M., & Robinson, S. (2021). Analyzing a faculty online learning community as a mechanism for supporting faculty implementation of a guided-inquiry curriculum. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R., & Mahmood, N. (2010). The relationship between test anxiety and academic achievement (SSRN scholarly paper no. 2362291). Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2362291 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Raymer, R., & Poppen, R. (1985). Behavioral relaxation training with hyperactive children. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 16(4), 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romans, S. K., Wills, H. P., Huffman, J. M., & Garrison-Kane, L. (2020). The effect of web-based self-monitoring to increase on-task behavior and academic accuracy of high school students with autism. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 64(3), 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, B. V., Melgarejo, M., & Suhrheinrich, J. (2022). Proactive versus reactive: Strategies in the implementation of school-based services for students with ASD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 49(4), 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, P. J., Walerius, D. M., Fogleman, N. D., & Factor, P. I. (2015). The association of emotional lability and emotional and behavioral difficulties among children with and without ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 7(4), 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer Whitby, P. J., & Mancil, G. R. (2009). Academic achievement profiles of children with high functioning autism and asperger syndrome: A review of the literature. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44(4), 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, D. J., & Poppen, R. (1983). Behavioral relaxation training and assessment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 14(2), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. F., Mokros, A., & Banse, R. (2013). Is pedophilic sexual preference continuous? A taxometric analysis based on direct and indirect measures. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Contreras, B., Krieger, J., Grgic, J., Delcastillo, K., Belliard, R., & Alto, A. (2019). Resistance training volume enhances muscle hypertrophy but not strength in trained men. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(1), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, N. A., & Mathur, S. R. (2009). Effects of cognitive-behavioral intervention on the school performance of students with emotional or behavioral disorders and anxiety. Behavioral Disorders, 34(4), 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenouda, J., Barrett, E., Davidow, A. L., Sidwell, K., Lescott, C., Halperin, W., Silenzio, V. M. B., & Zahorodny, W. (2023). Prevalence and disparities in the detection of autism without intellectual disability. Pediatrics, 151(2), e2022056594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, N. C., Rosli, R., Maat, S. M., Alias, A., Toran, H., Mottan, K., & Nor, S. M. (2020). The impacts of mathematics instructional strategy on students with autism: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Educational Research, 9(2), 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B. F. (1965). Science and human behavior. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solari, E. J., Grimm, R., McIntyre, N. S., Lerro, L. S.-, Zajic, M., & Mundy, P. C. (2017). The relation between text reading fluency and reading comprehension for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 41–42, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatum, T., Lundervold, D. A., & Ament, P. (2006). Abbreviated upright behavioral relaxation training for test anxiety among college students: Initial results. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 2(4), 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton-Fisler, L. A., & Knight, E. (2024). A review of group design studies of reading comprehension interventions for students with ASD. Contemporary School Psychology, 28(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasa, R. A., & Mazurek, M. O. (2015). An update on anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(2), 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitasari, P., Wahab, M. N. A., Othman, A., & Awang, M. G. (2010). The use of study anxiety intervention in reducing anxiety to improve academic performance among university students. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 2, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Fredricks, J. A., Simpkins, S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2015). Development of achievement motivation and engagement. In Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 1–44). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C. J., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2014). The effect of emotion regulation strategies on physiological and self-report measures of anxiety during a stress-inducing academic task. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. J., & Symons, F. J. (2013). An evaluation of multi-component exposure treatment of needle phobia in an adult with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26(4), 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. (2006). Effect of anxiety reduction on children’s school performance and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. The Effects of Behavioral Relaxation Training on Academic Task Completion Among Students with Autism in Inclusive Classrooms: A Single-Subject Design Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121633

Jiang Y, Liu H, Wang Y, Hu X. The Effects of Behavioral Relaxation Training on Academic Task Completion Among Students with Autism in Inclusive Classrooms: A Single-Subject Design Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121633

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yitong, Hongmei Liu, Yin Wang, and Xiaoyi Hu. 2025. "The Effects of Behavioral Relaxation Training on Academic Task Completion Among Students with Autism in Inclusive Classrooms: A Single-Subject Design Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121633

APA StyleJiang, Y., Liu, H., Wang, Y., & Hu, X. (2025). The Effects of Behavioral Relaxation Training on Academic Task Completion Among Students with Autism in Inclusive Classrooms: A Single-Subject Design Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121633