More than Just Aversive: A Network Analysis of the Dark Triad, Coping, and Psychopathology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Dark Triad, Psychopathology, and Coping

1.2. Network Analysis

1.3. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dark Triad Traits

2.2.2. Coping with Stress

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

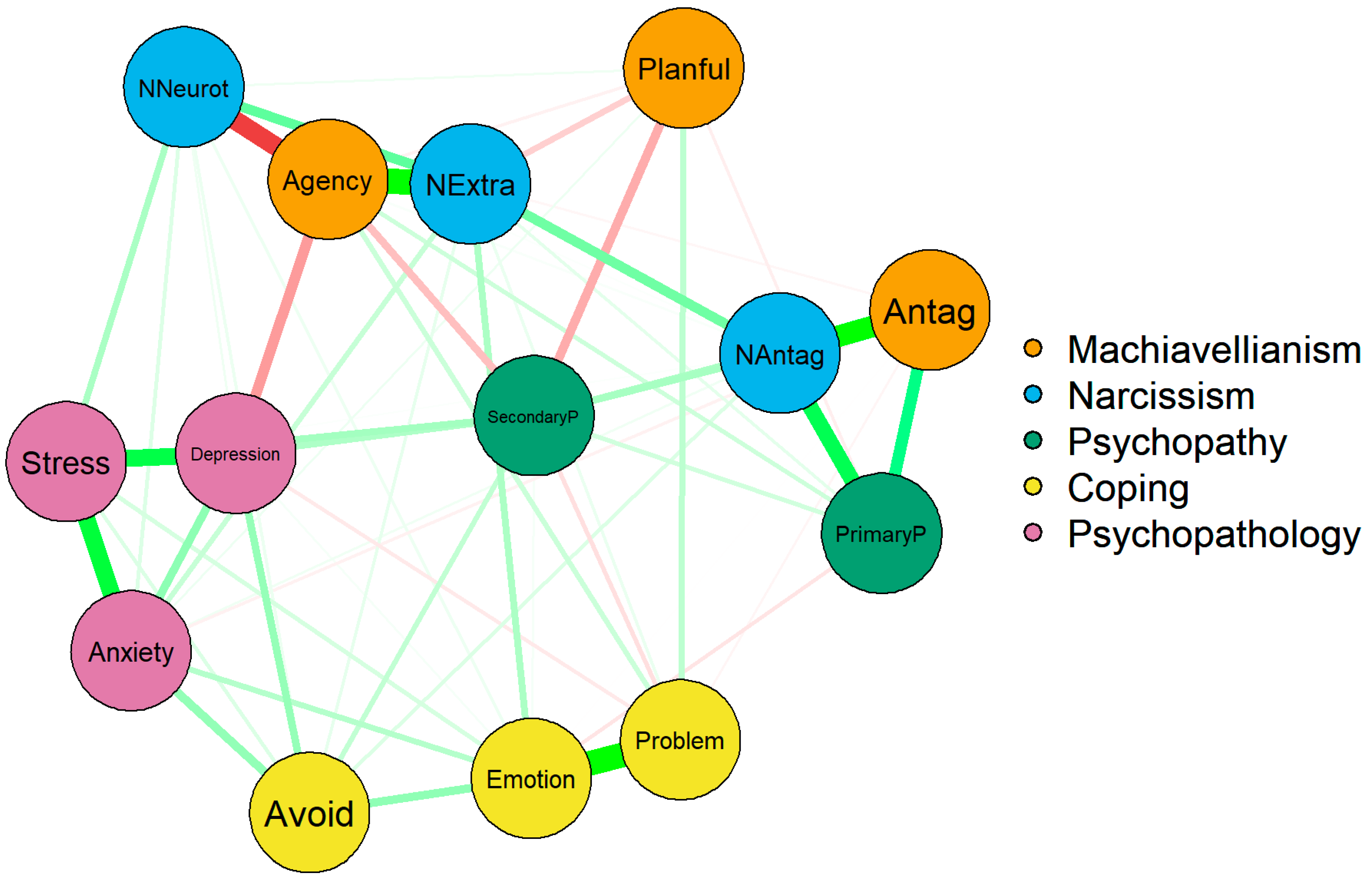

3.1. Network Analysis of Dark Triad Factors, Psychopathology, and Coping

3.1.1. Stability and Accuracy

3.1.2. Dark Triad Factors and Psychopathology

3.1.3. Dark Triad Factors, Coping, and Psychopathology

3.1.4. Dark Triad Factors—Centrality

3.1.5. Predictability

3.1.6. Expected Influence

4. Discussion

4.1. Coping

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Implications for Theory and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FFNI | Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory |

| FFMI | Five-Factor Machiavellianism Inventory |

| FFNI-SF | Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory – Short Form |

| M | Machiavellianism |

| Antag | Antagonism |

| Plan | Planfullness |

| P | Psychopathy |

| N | Narcissism |

| Extra | Extraversion |

| Neurot | Neuroticism |

| Problem | Problem-focused coping |

| Emotion | Emotion-focused coping |

| Avoid | Avoidance-focused coping |

References

- Aghababaei, N., & Błachnio, A. (2015). Well-being and the dark triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkás, B., Gács, B., & Csathó, Á. (2016). Keep calm and don’t worry: Different dark triad traits predict distinct coping preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D., Deserno, M. K., Rhemtulla, M., Epskamp, S., Fried, E. I., McNally, R. J., Robinaugh, D. J., Perugini, M., Dalege, J., Costantini, G., Isvoranu, A. M., Wysocki, A. C., van Borkulo, C. D., van Bork, R., & Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. In Nature reviews methods primers (Vol. 1, Issue 1). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, G., Fried, E. I., & Linkowski, P. (2019). Network analysis of Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale in 680 university students. Psychiatry Research, 272, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collison, K. L., Vize, C. E., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2018). Development and preliminary validation of a five factor model measure of Machiavellianism. Psychological Assessment, 30(10), 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G., Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., Perugini, M., Mõttus, R., Waldorp, L. J., & Cramer, A. O. (2015). State of the aRt personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. Journal of Research in Personality, 54, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, V., Chan, S., & Shorter, G. W. (2014). The Dark triad, happiness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Generalized network psychometrics: Combining network and latent variable models. Psychometrika, 82(4), 904–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, B. A., Fung, A., & Nikčević, A. V. (2016). Different coping strategies amongst individuals with grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic traits. Journal of Affective Disorders, 205, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. (2007). Organization behavior research companion to the dysfunctional workplace, management challenges an. In J. Langan-Fox, C. L. Cooper, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Research companion to the dysfunctional workplace (pp. 22–29). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Gojković, V., Dostanić, J., & Durić, V. (2022). Structure of darkness: The dark triad, the “dark” empathy and the “dark” narcissism. Primenjena Psihologija, 15(2), 237–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H. F., & Epskamp, S. (2017). Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0174035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabovac, B., & Dinić, B. M. (2022). “The devil in disguise”: A test of Machiavellianism instruments (the Mach-IV, the machiavellian personality scale, and the five factor machiavellianism inventory). Primenjena Psihologija, 15(3), 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosack, L. L., Welton, G. L., & Homan, K. J. (2023). Differentiation of self and internal distress: The mediating roles of vulnerable narcissism and maladaptive perfectionism. Clinical Social Work Journal, 51, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Fei, X., Liu, H., Roeder, K., Lafferty, J., Wasserman, L., Li, X., & Zhao, T. (2020). Package ‘huge’. R Package Version, 1(4.1). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., Tong, L., Cao, W., & Wang, H. (2024). Dark triad and relational aggression: The mediating role of relative deprivation and hostile attribution bias. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1487970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., Jones, A., & Lyons, M. (2013). Creatures of the night: Chronotypes and the dark triad traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J., Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., Gebauer, J. E., Maltby, J., Adamovic, M., Adams, B. G., Kadiyono, A. L., Atitsogbe, K. A., Bundhoo, H. Y., Bălțătescu, S., Bilić, S., Brulin, J. G., Chobthamkit, P., Del Carmen Dominguez, A., Dragova-Koleva, S., El-Astal, S., … Yahiiaev, I. (2020). Country-level correlates of the dark triad traits in 49 countries. Journal of Personality, 88(6), 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdy, R., & Petot, J. M. (2017). Relationships between personality traits and depression in the light of the “big five” and their different facets. L’évolution Psychiatrique, 82(4), e27–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajonius, P. J., & Björkman, T. (2020). Dark malevolent traits and everyday perceived stress. Current Psychology, 39(6), 2351–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. (2015). The impact of coping flexibility on the risk of depressive symptoms. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0128307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeffler, L. A. K., Huebben, A. K., Radke, S., Habel, U., & Derntl, B. (2020). The association between vulnerable/grandiose narcissism and emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M., Evans, K., & Helle, S. (2019). Do “dark” personality features buffer against adversity? The associations between cumulative life stress, the dark triad, and mental distress. Sage Open, 9(1), 2158244018822383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M. D., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2016). Relations among personality characteristics, environmental events, coping behavior and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansueto, A. C., Wiers, R. W., van Weert, J. C. M., Schouten, B. C., & Epskamp, S. (2022). Investigating the feasibility of idiographic network models. Psychological Methods, 28(5), 1052–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Back, M. D., Lynam, D. R., & Wright, A. G. (2021). Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Gaughan, E. T., & Pryor, L. R. (2008). The levenson self-report psychopathy scale an examination of the personality traits and disorders associated with the LSRP Factors. Assessment, 15, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., McCain, J. L., Few, L. R., Crego, C., Widiger, T. A., & Campbell, W. K. (2016). Thinking structurally about narcissism: An examination of the five-factor narcissism inventory and its components. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, C., Bizumic, B., & Sellbom, M. (2018). Nomological network of two-dimensional Machiavellianism. Personality and Individual Differences, 130, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H. K., Cheung, R. Y. H., & Tam, K. P. (2014). Unraveling the link between narcissism and psychological health: New evidence from coping flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K. A., Benini, E., Bilello, D., Gianniou, F. M., Clough, P. J., & Costantini, G. (2019a). Bridging the gap: A network approach to dark triad, mental toughness, the big five, and perceived stress. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, K. A., Denovan, A., & Dagnall, N. (2019b). The positive effect of narcissism on depressive symptoms through mental toughness: Narcissism may be a dark trait but it does help with seeing the world less grey. European Psychiatry, 55, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, K. A., Gianniou, F. M., Wilson, P., Moneta, G. B., Bilello, D., & Clough, P. J. (2019c). The bright side of dark: Exploring the positive effect of narcissism on perceived stress through mental toughness. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. (2025). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Posit Software, PBC. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sherman, E. D., Miller, J. D., Few, L. R., Campbell, W. K., Widiger, T. A., Crego, C., & Lynam, D. R. (2015). Development of a short form of the five-factor narcissism inventory: The FFNI-SF. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truhan, T. E., Wilson, P., Mõttus, R., & Papageorgiou, K. A. (2021). The many faces of dark personalities: An examination of the dark triad structure using psychometric network analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, S., Skeem, J., & Camp, J. (2010). Emotional intelligence: Painting different paths for low-anxious and high-anxious psychopathic variants. Law and Human Behavior, 34(2), 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M., Li, J., Wang, X., Su, Z., & Luo, Y. L. (2025). Will the dark triad engender psychopathological symptoms or vice versa? A three-wave random intercept cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Personality, 93(3), 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Distinguishing between grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality disorder. In Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 3–13). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Mean (SD) | Variance | Skew | Kurtosis | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narcissism | |||||

| Antagonism | 72.64 (19.19) | 369.23 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.91 |

| Extraversion | 47.50 (12.69) | 161.05 | −0.09 | −0.65 | 0.89 |

| Neuroticism | 38.16 (8.51) | 72.42 | −0.24 | −0.49 | 0.81 |

| Machiavellianism | |||||

| Agency | 76.03 (16.65) | 277.17 | −0.12 | −0.41 | 0.90 |

| Antagonism | 47.78 (11.64) | 135.55 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Planfulness | 29.14 (4.67) | 21.75 | −0.41 | 0.25 | 0.76 |

| Psychopathy | |||||

| Primary | 33.28 (7.96) | 63.41 | 0.62 | −0.03 | 0.88 |

| Secondary | 22.27 (4.91) | 24.15 | 0.32 | −0.16 | 0.74 |

| Coping | |||||

| Problem | 20.76 (5.37) | 28.89 | −0.16 | −0.38 | 0.85 |

| Avoidance | 14.60 (4.18) | 17.47 | 0.75 | 0.06 | 0.73 |

| Emotion | 26.81 (5.87) | 34.42 | 0.02 | −0.31 | 0.71 |

| Psychopathology | |||||

| Depression | 27.67 (10.50) | 110.15 | 0.67 | −0.3 | 0.92 |

| Anxiety | 23.81 (8.51) | 72.46 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 0.85 |

| Stress | 28.76 (8.58) | 73.54 | 0.30 | −0.2 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M agency | |||||||||||||

| 2. M antag | 0.10 | ||||||||||||

| 3. M plan | −0.11 * | −0.20 ** | |||||||||||

| 4. Primary P | 0.24 ** | 0.71 ** | −0.28 ** | ||||||||||

| 5. Secondary P | −0.32 ** | 0.47 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.42 ** | |||||||||

| 6. N antag | 0.22 ** | 0.78 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.75 ** | 0.48 ** | ||||||||

| 7. N extra | 0.63 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.09 | 0.50 ** | |||||||

| 8. N neurot | −0.59 ** | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.35 ** | 0.08 | −0.06 | ||||||

| 9. Problem | 0.28 ** | −0.08 | 0.15 ** | −0.07 | −0.17 ** | 0.05 | 0.29 ** | −0.07 | |||||

| 10. Emotion | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.14 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.60 ** | ||||

| 11. Avoid | −0.19 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.13 * | 0.22 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.06 | 0.37 ** | |||

| 12. Depression | −0.52 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.53 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.10 | 0.54 ** | −0.11 * | 0.24 ** | 0.55 ** | ||

| 13. Anxiety | −0.22 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.04 | 0.16 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.12 * | 0.40 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.66 ** | |

| 14. Stress | −0.36 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.07 | 0.15 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.07 | 0.53 ** | 0.05 | 0.33 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.76 ** |

| Variable | Predictability |

|---|---|

| Stress | 0.67 |

| Depression | 0.65 |

| Anxiety | 0.59 |

| Emotion-focused coping | 0.50 |

| Problem-focused coping | 0.42 |

| Avoidance-focused coping | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McIlvenna, M.; Truhan, T.; Papageorgiou, K. More than Just Aversive: A Network Analysis of the Dark Triad, Coping, and Psychopathology. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121617

McIlvenna M, Truhan T, Papageorgiou K. More than Just Aversive: A Network Analysis of the Dark Triad, Coping, and Psychopathology. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121617

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcIlvenna, Micheala, Tayler Truhan, and Kostas Papageorgiou. 2025. "More than Just Aversive: A Network Analysis of the Dark Triad, Coping, and Psychopathology" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121617

APA StyleMcIlvenna, M., Truhan, T., & Papageorgiou, K. (2025). More than Just Aversive: A Network Analysis of the Dark Triad, Coping, and Psychopathology. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121617