Efficacy of Coping with Negative Affect via Alcohol Use Pre- and Post Acute Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Substance Use Coping

2.3.2. Negative Mood

2.3.3. Alcohol Use

2.3.4. Covariates

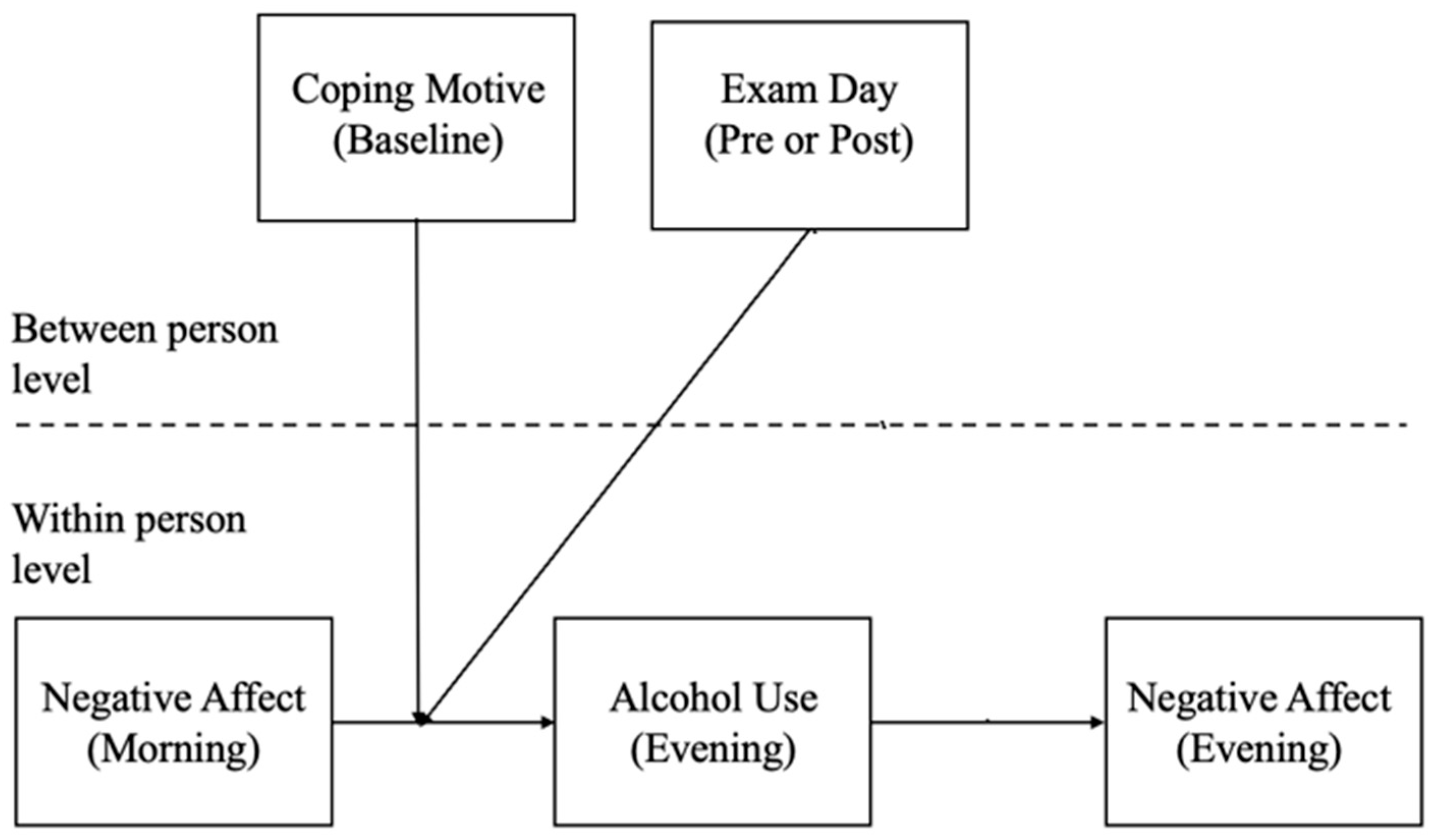

2.4. Analytic Plan

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge-Gerry, A. A., Roesch, S. C., Villodas, F., McCabe, C., Leung, Q. K., & Da Costa, M. (2011). Daily stress and alcohol consumption: Modeling between-person and within-person ethnic variation in coping behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(1), 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalil, K., Vakamudi, K., Witkiewitz, K., & Claus, E. D. (2021). Neural correlates of alcohol use disorder severity among nontreatment-seeking heavy drinkers: An examination of the incentive salience and negative emotionality domains of the alcohol and addiction research domain criteria. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(6), 1200–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. G., Garcia, T. A., & Dash, G. F. (2017). Drinking motives and willingness to drink alcohol in peer drinking contexts. Emerging Adulthood, 5(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, E. B., Rando, K., Tuit, K., Guarnaccia, J., & Sinha, R. (2012). Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biological Psychiatry, 72(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthenelli, R. M. (2012). Overview: Stress and alcohol use disorders revisited. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 34(4), 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeli, S., Carney, M. A., Tennen, H., Affleck, G., & O’Neil, T. P. (2000). Stress and alcohol use: A daily process examination of the stressor–vulnerability model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armeli, S., Tennen, H., Todd, M., Carney, M. A., Mohr, C., Affleck, G., & Hromi, A. (2003). A daily process examination of the stress-response dampening effects of alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(4), 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpin, S. N., Mohr, C. D., Bodner, T. E., Hammer, L. B., & Lee, J. D. (2025). Prospective associations among loneliness and health for servicemembers: Perceived helplessness and negative coping appraisal as explanatory mechanisms. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T. B., Piper, M. E., McCarthy, D. E., Majeskie, M. R., & Fiore, M. C. (2004). Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111(1), 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehler, K. M., Jenzer, T., & Read, J. P. (2024). Daily-level self-compassion and coping-motivated drinking. Mindfulness, 15, 1846–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsoih, J., Patock-Peckham, J. A., Canning, J. R., Ong, A., Becerra, A., & Broussard, M. (2023). Do coping motives and perceived impaired control mediate the indirect links from childhood trauma facets to alcohol-related problems? Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, S. K., Nautiyal, N., Hart, R., Guarnaccia, J. B., & Sinha, R. (2019). Craving, cortisol and behavioral alcohol motivation responses to stress and alcohol cue contexts and discrete cues in binge and non-binge drinkers. Addiction Biology, 24(5), 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N. (1990). Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(3), 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, N., & Schilling, E. A. (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59(3), 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N., & Zuckerman, A. (1995). A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, D. E., Shapiro, B. L., & Curtin, J. J. (2013). How bad could it be? Alcohol dampens stress responses to threat of uncertain intensity. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresin, K. (2019). A meta-analytic review of laboratory studies testing the alcohol stress response dampening hypothesis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(7), 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslin, C. F., O’Keeffe, M. K., Burrell, L., Ratliff-Crain, J., & Baum, A. (1995). The effects of stress and coping on daily alcohol use in women. Addictive Behaviors, 20(2), 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R. W., & Merrill, J. E. (2021). How much and how fast: Alcohol consumption patterns, drinking-episode affect, and next-day consequences in the daily life of underage heavy drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofresí, R. U., Bartholow, B. D., & Piasecki, T. M. (2019). Evidence for incentive salience sensitization as a pathway to alcohol use disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 897–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Mudar, P. (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M. L., Kuntsche, E., Levitt, A., Barber, L. L., & Wolf, S. (2016). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In K. J. Sher (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders (pp. 375–421). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. L., Russell, M., & George, W. H. (1988). Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. L., Russell, M., Skinner, J. B., Frone, M. R., & Mudar, P. (1992). Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(1), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croissant, B., & Olbrich, R. (2004). Stress response dampening indexed by cortisol in subjects at risk for alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(6), 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 583–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C. E. (1990). Stress and social support—In search of optimal matching. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, J., Piccirillo, M., Foster, K. T., Arbeau, K., Armeli, S., Auriacombe, M., Bartholow, B., Beltz, A. M., Blumenstock, S. M., Bold, K., Bonar, E. E., Braitman, A., Carpenter, R. W., Creswell, K. G., De Hart, T., Dvorak, R. D., Emery, N., Enkema, M., Fairbairn, C., … King, K. M. (2023). The daily association between affect and alcohol use: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. Psychological Bulletin, 149(1–2), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, K. K., Mun, C. J., Connell, A., & Ha, T. (2023). Coping strategies as mediating mechanisms between adolescent polysubstance use classes and adult alcohol and substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 139, 107586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, B. J., & Revenson, T. A. (1984). Coping with chronic illness: A study of illness controllability and the influence of coping strategies on psychological adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52(3), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, M., Stock, M. L., Roberts, M. E., Gibbons, F. X., O’Hara, R. E., Weng, C. Y., & Wills, T. A. (2012). Coping with racial discrimination: The role of substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, M. D., Bharat, C., Degenhardt, L., Sampson, N. A., Scott, K. M., Lim, C. C., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Andrade, L. H., Cardoso, G., De Girolamo, G., Gureje, O., He, Y., Hinkov, H., Karam, E. G., Karam, G., Kovess-Masfety, V., Lasebikan, V., Lee, S., … WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. (2020). The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: Findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Addictive Behaviors, 102, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinle, M. I. B., & Sinha, R. (2020). The role of stress, trauma, and negative affect in alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorder in women. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(2), 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A. M., & Chassin, L. (1994). The stress-negative affect model of adolescent alcohol use: Disaggregating negative affect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55(6), 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussong, A. M., Ennett, S. T., McNeish, D., Rothenberg, W. A., Cole, V., Gottfredson, N. C., & Faris, R. W. (2018). Teen social networks and depressive symptoms-substance use associations: Developmental and demographic variation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(5), 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, M., Gleason, M., Green-Rapaport, A. S., Bolger, N., & Shrout, P. E. (2017). The influence of daily coping on anxiety under examination stress: A model of interindividual differences in intraindividual change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(7), 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y. (2001). Testing an optimal matching hypothesis of stress, coping and health: Leisure and general coping. Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure, 24(1), 163–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juth, V., Dickerson, S. S., Zoccola, P. M., & Lam, S. (2015). Understanding the utility of emotional approach coping: Evidence from a laboratory stressor and daily life. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 28(1), 50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, R. J., Roth, K. A., & Carroll, B. J. (1981). Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: Implications for a model of depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 5(2), 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, K. M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. S. (2012). Stress and alcohol: Epidemiologic evidence. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 34(4), 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klenk, M. M., Strauman, T. J., & Higgins, E. T. (2011). Regulatory focus and anxiety: A self-regulatory model of GAD-depression comorbidity. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2010). Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, E., Knibbe, R., Gmel, G., & Engels, R. (2005). Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(7), 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, E., Knibbe, R., Gmel, G., & Engels, R. (2006). Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors, 31(10), 1844–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R. I. (1994). The effect of moderate alcohol use on the relationship between stress and depression. American Journal of Public Health, 84(12), 1913–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, P. M., Canham, S. L., Martins, S. S., & Spira, A. P. (2015). Substance-use coping and self-rated health among US middle-aged and older adults. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, K. A., & Kessler, R. C. (1990). Chronic stress, acute stress, and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(5), 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1971). Manual for the profile of mood states (POMS). Educational and Industrial Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi, T. V., Philip, E. J., Yang, M., & Heitzmann, C. A. (2016). Matching of received social support with need for support in adjusting to cancer and cancer survivorship. Psycho-Oncology, 25(6), 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 110(3), 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T. J., Mathias, C. W., Mullen, J., Karns-Wright, T. E., Hill-Kapturczak, N., Roache, J. D., & Dougherty, D. M. (2019). The role of social support in motivating reductions in alcohol use: A test of three models of social support in alcohol-impaired drivers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(1), 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, N. E., & Cohen, D. J. (1997). Changes in substance use during times of stress: College students the week before exams. Journal of Drug Education, 27(4), 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D. B., Thayer, J. F., & Vedhara, K. (2021). Stress and health: A review of psychobiological processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patock-Peckham, J. A., Corbin, W. R., Smyth, H., Canning, J. R., Ruof, A., & Williams, J. (2022). Effects of stress, alcohol prime dose, and sex on ad libitum drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Révész, D., Bours, M. J., Weijenberg, M. P., & Mols, F. (2022). Longitudinal associations of former and current alcohol consumption with psychosocial outcomes among colorectal cancer survivors 1–15 years after diagnosis. Nutrition and Cancer, 74(9), 3109–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, N. (2012). Acute and chronic stress induced changes in sensitivity of peripheral inflammatory pathways to the signals of multiple stress systems–2011 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(3), 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, N. (2019). Stress and inflammation–The need to address the gap in the transition between acute and chronic stress effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 105, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, K. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1982). Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response-dampening effect of alcohol. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 91(5), 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Lane, S. P. (2012). Psychometrics. In M. R. Mehl, & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 302–320). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E., Stadler, G., Lane, S. P., McClure, M. J., Jackson, G. L., Clavél, F. D., Iida, M., Gleason, M. E., Xu, J. H., & Bolger, N. (2018). Initial elevation bias in subjective reports. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(1), E15–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, J., Bolger, N., & Ochsner, K. N. (2021). Social emotion regulation strategies are differentially helpful for anxiety and sadness. Emotion, 21(6), 1144–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R. (2024). Stress and substance use disorders: Risk, relapse, and treatment outcomes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 134(16), e172883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanesby, O., Labhart, F., Dietze, P., Wright, C. J., & Kuntsche, E. (2019). The contexts of heavy drinking: A systematic review of the combinations of context-related factors associated with heavy drinking occasions. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0218465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M., & Josephs, R. A. (1990). Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist, 45(8), 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltzfus, K. M., & Farkas, K. J. (2012). Alcohol use, daily hassles, and religious coping among students at a religiously affiliated college. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(10), 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, H., & Miranda, R., Jr. (2017). Craving and acute effects of alcohol in youths’ daily lives: Associations with alcohol use disorder severity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(4), 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, P. F., Graham, K., Wells, S., Harris, R., Pulford, R., & Roberts, S. E. (2010). When do first-year college students drink most during the academic year? An internet-based study of daily and weekly drinking. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, M. Y., Lemmens, P. H., Friesema, I. H., Tan, F. E., Garretsen, H. F., Knottnerus, J. A., & Zwietering, P. J. (2007). Coping style mediates impact of stress on alcohol use: A prospective population-based study. Addiction, 102(12), 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. E., Dvorak, R. D., Ebbinghaus, A., Gius, B. K., Levine, J. A., Cortina, W., & Schlauch, R. C. (2023). Disaggregating within-and between-person effects of affect on drinking behavior in a clinical sample with alcohol use disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 132(8), 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N. (2019). Emerging adults’ received and desired support from parents: Evidence for optimal received–desired support matching and optimal support surpluses. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(11–12), 3448–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanous, J. P., & Reichers, A. E. (1996). Estimating the reliability of a single-item measure. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wemm, S. E., Tennen, H., Sinha, R., & Seo, D. (2022). Daily stress predicts later drinking initiation via craving in heavier social drinkers: A prospective in-field daily diary study. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 131(7), 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T. A. (1986). Stress and coping in early adolescence: Relationships to substance use in urban school samples. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 5(6), 503–529. [Google Scholar]

- Wycoff, A. M., Carpenter, R. W., Hepp, J., Piasecki, T. M., & Trull, T. J. (2021). Real-time reports of drinking to cope: Associations with subjective relief from alcohol and changes in negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(6), 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M., & Gagne, M. (2003). The COPE revised: Proposing a 5-factor model of coping strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(3), 169–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 160 | 70.8 |

| Male | 66 | 29.2 |

| Other Identity | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Straight | 209 | 93.3 |

| Gay or Lesbian | 6 | 2.7 |

| Bisexual | 6 | 2.7 |

| Other | 3 | 1.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity/Identity | ||

| Asian | 99 | 43.8 |

| White | 97 | 42.9 |

| Black | 15 | 6.6 |

| Native American | 6 | 2.7 |

| Pacific Islander | 3 | 1.3 |

| Hispanic | 29 | 13.0 |

| International | 63 | 27.9 |

| Other | 28 | 12.4 |

| Year in College | ||

| Freshman | 72 | 31.9 |

| Sophomore | 76 | 33.6 |

| Junior | 45 | 19.9 |

| Senior | 13 | 5.8 |

| Other | 20 | 8.9 |

| Exam Course | ||

| Chemistry | 125 | 55.3 |

| Biology | 75 | 33.2 |

| Physics | 26 | 11.5 |

| N | % | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 226 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 2.1 | 18–29 |

| Drinking Days | 226 | 100.0 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0 (108), 1 (40), 2 (23), 3 (24), 4 + (31) |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 118 | 52.2 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 1–17 |

| Other Substance Use Days | 226 | 100.0 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 0 (175), 1 (16), 2 (12), 3 (4), 4 + (19) |

| Substance Use Coping | 226 | 100.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0 (179), 1 (33), 2 (12), 3 (2) |

| M | SDBtw | SDWth | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Coping | 0.28 | 0.60 | – | – | – | – | |

| 2. | # Drinks per Day | 0.39 | 0.61 | 1.25 | 0.33 *** | −0.05 * | −0.04 * | |

| 3. | Morning NA | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.27 *** | −0.02 | 0.34 *** | |

| 4. | Evening NA | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.26 *** | −0.04 | 0.95 *** |

| Pre-Exam | Post-Exam | Post-Pre Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p |

| ALCOHOL USE | |||||||||

| Intercept | 0.308 | 0.041 | <0.001 | 0.440 | 0.037 | <0.001 | 0.132 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

| Coping | 0.086 | 0.037 | 0.020 | 0.204 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 0.118 | 0.039 | 0.003 |

| Within | |||||||||

| Morning NA | −0.034 | 0.025 | 0.171 | −0.074 | 0.022 | 0.001 | −0.039 | 0.034 | 0.247 |

| Morning NA * Coping | −0.018 | 0.026 | 0.488 | −0.068 | 0.023 | 0.004 | −0.050 | 0.036 | 0.162 |

| Between | |||||||||

| Morning NA | 0.021 | 0.034 | 0.531 | −0.048 | 0.030 | 0.105 | −0.069 | 0.037 | 0.063 |

| Morning NA * Coping | −0.014 | 0.024 | 0.542 | −0.038 | 0.022 | 0.080 | −0.024 | 0.027 | 0.377 |

| EVENING NA | |||||||||

| Intercept | 1.009 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 1.009 | 0.030 | <0.001 | |||

| Within | |||||||||

| Morning NA | 0.230 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.230 | 0.016 | <0.001 | |||

| # Drinks | −0.043 | 0.012 | <0.001 | −0.043 | 0.012 | <0.001 | |||

| Between | |||||||||

| Morning NA | 0.728 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.728 | 0.016 | <0.001 | |||

| # Drinks | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.165 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.1645 | |||

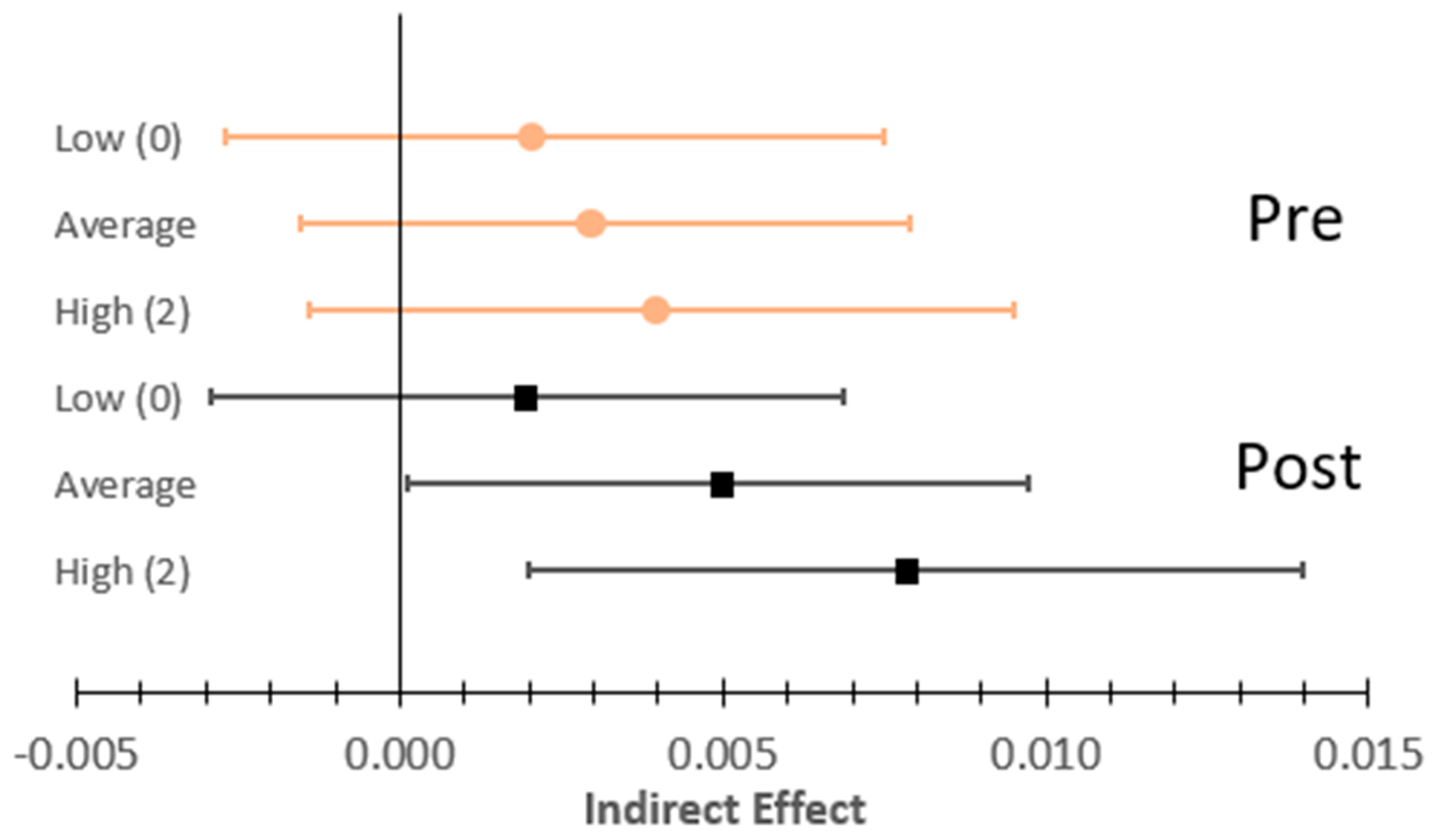

| Within Indirect Effect | β | 5% | 95% | β | 5% | 95% | |||

| Low (0) Coping | 0.0024 | −0.0027 | 0.0075 | 0.0019 | −0.0029 | 0.0068 | |||

| Average Coping | 0.0031 | −0.0015 | 0.0079 | 0.0048 | 0.0001 | 0.0097 | |||

| High (2) Coping | 0.0039 | −0.0014 | 0.0095 | 0.0077 | 0.0020 | 0.0140 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Willis, M.A.; Ran, T.; Lane, S.P. Efficacy of Coping with Negative Affect via Alcohol Use Pre- and Post Acute Stress. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121614

Willis MA, Ran T, Lane SP. Efficacy of Coping with Negative Affect via Alcohol Use Pre- and Post Acute Stress. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121614

Chicago/Turabian StyleWillis, Mairéad A., Tongyao Ran, and Sean P. Lane. 2025. "Efficacy of Coping with Negative Affect via Alcohol Use Pre- and Post Acute Stress" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121614

APA StyleWillis, M. A., Ran, T., & Lane, S. P. (2025). Efficacy of Coping with Negative Affect via Alcohol Use Pre- and Post Acute Stress. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121614