The Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment and Path Analysis—Evidence from the China Education Panel Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Physical Exercise and School Adjustment

1.2. The Mediating Role of Negative Emotions

1.3. The Mediating Role of Pro-Social Behavior

1.4. Current Study Aims

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Variable Selection

2.2.1. School Adjustment

2.2.2. Physical Exercise

2.2.3. Negative Emotions

2.2.4. Prosocial Behavior

2.2.5. Control Variable

2.3. Empirical Strategy

2.3.1. OLS Regression

2.3.2. Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

2.3.3. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

2.3.4. KHB Mediation Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Regression Modeling of Physical Exercise as It Affects Adolescents’ School Adjustment

3.2. Robustness Tests

3.2.1. Instrumental Variable Method

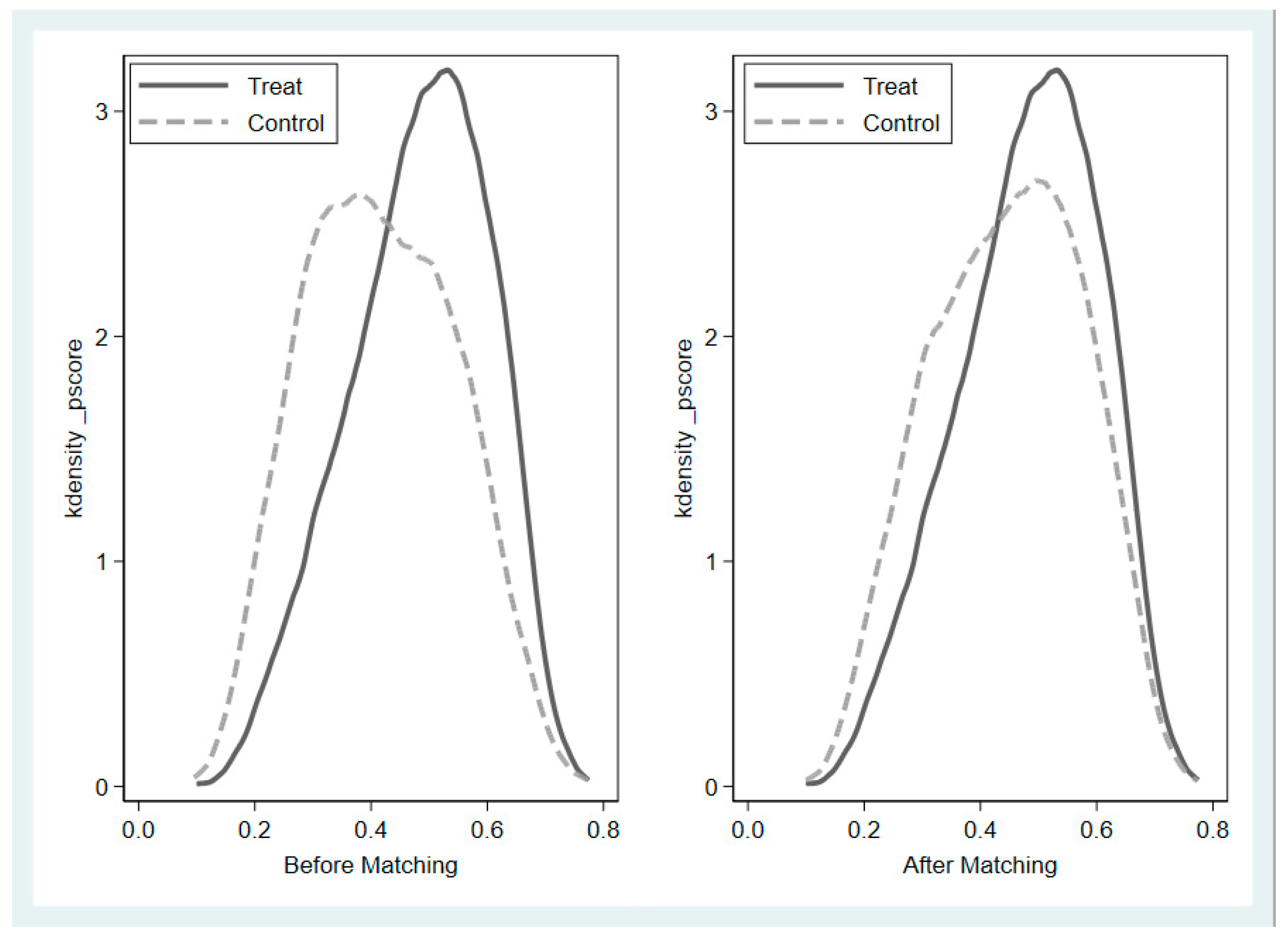

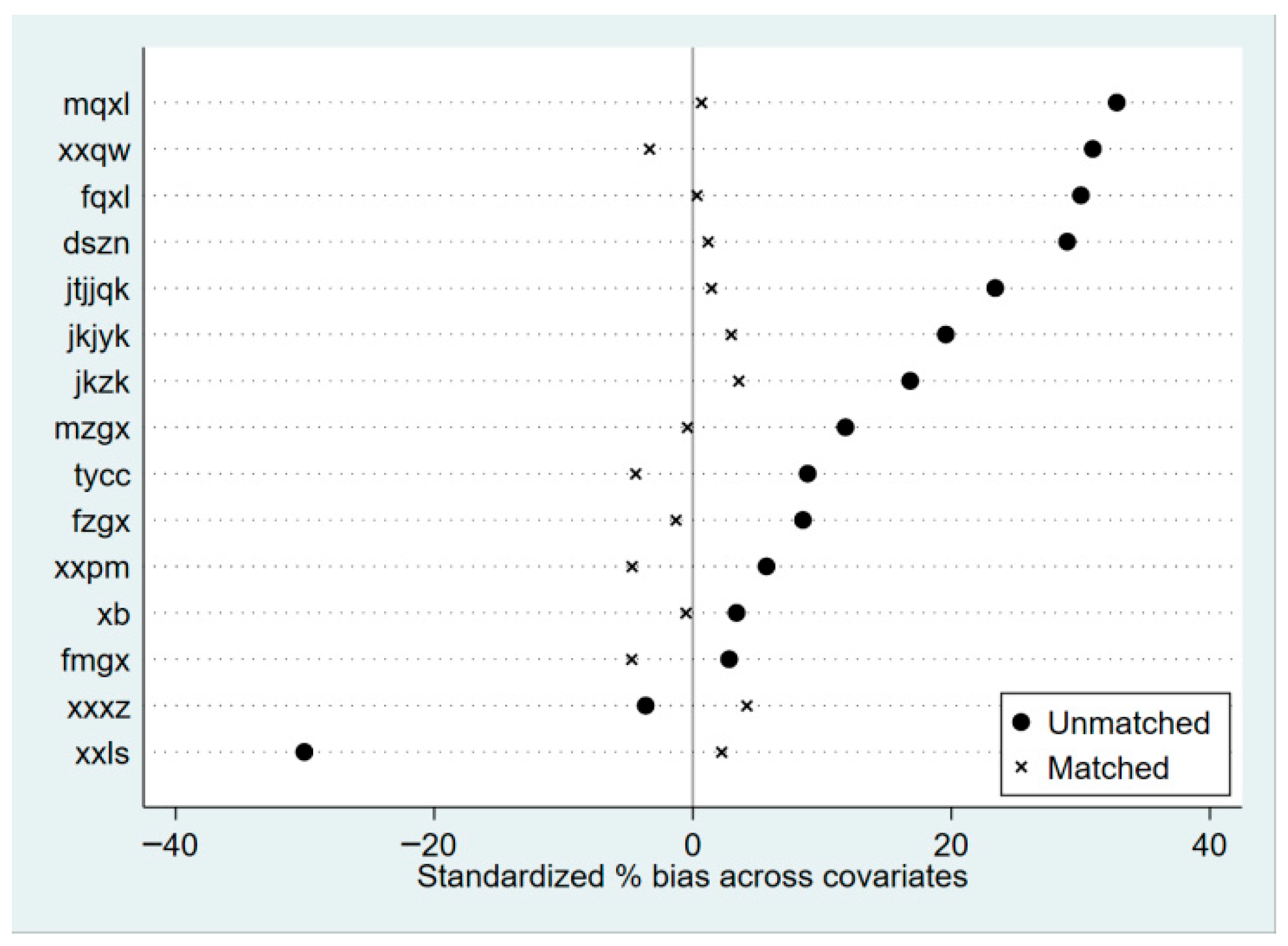

3.2.2. Propensity Score Matching

3.2.3. Mediation Effect Test Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Direct Impact of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment

4.2. The Indirect Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment

4.3. Recommendation

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azpiazu, L., Antonio-Aguirre, I., Izar-de-la-Funte, I., & Fernández-Lasarte, O. (2024). School adjustment in adolescence explained by social support, resilience and positive affect. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(4), 3709–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M., Yao, S., Ma, Q., Wang, X., Liu, C., & Guo, K. (2022). The relationship between physical exercise and school adaptation of junior students: A chain mediating model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 977663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M., Yang, H., & Chen, D. (2023). Relationship between anxiety and problematic smartphone use in first-year junior high school students: Moderated mediation effects of physical activity and school adjustment. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M., Zhang, G., Sun, Z., & Zhang, H. (2018). Mediating effects of elementary school students’ self-perceptions between physical activity and school adjustment. Chinese Journal of School Health, 39(01), 122–123+129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Lu, T., Sui, H., Liu, C., Gao, Y., Tao, B., & Yan, J. (2024). The relationship between physical activity and school adjustment in high school students: The chain mediating role of psychological resilience and self-control. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Yu, P. (2015). The influence of physical exercise on subjective well-being of college students: An intermediary effect of peer relationship. Journal of Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, 27(2), 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., Roberts, C. L., & Nassar, N. (2018). The roles of anxious and prosocial behavior in early academic performance: A population-based study examining unique and moderated effects. Learning and Individual Differences, 62, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, M., & Ünal, G. (2024). Promoting prosocial behavior in school setting. In G. Arslan, & M. Yıldırım (Eds.), Handbook of positive school psychology. Advances in mental health and addiction. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtaş, Z. S., & Ergene, T. (2019). School adjustment of first-grade primary school students: Effects of family involvement, externalizing behavior, teacher and peer relations. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X., Wang, X., Li, X., Li, S., Zhong, Y., & Bu, T. (2022). Effect of mass sports activity on prosocial behavior: A sequential mediation model of flow trait and subjective wellbeing. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 960870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eather, N., Wade, L., Pankowiak, A., & Eime, R. (2023). The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: A systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2015). Prosocial development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., & Rao, S. (2021). Worldwide development of physical activity guidelines for children and adolescents. China Sport Science and Technology, 57(8), 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havighurst, R. J. (1975). Objectives for youth development. Teachers College Record, 76(5), 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M. M., Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., Spinrad, T. L., Berger, R. H., VanSchyndel, S. K., Silva, K. M., Diaz, A., Thompson, M. S., Gal, D. E., & Southworth, J. (2018). Bidirectional associations between emotions and school adjustment. Journal of Personality, 86, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillekens, J., Baysu, G., & Phalet, K. (2023). How school and home contexts impact the school adjustment of adolescents from different ethnic and SES backgrounds during COVID-19 school closures. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(8), 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q., Guo, M., Wang, L., Lv, H., & Chang, S. (2022). The relationship between school assets and early adolescents’ psychosocial adaptation: A latent transition analysis. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 54(8), 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P., & Yu, F. (2019). A study about the restrictive factors on physical exercise of the middle school students—An HLM model based on CEPS (2014–2015). China Sport Science, 39(1), 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z., Guo, K., Liu, C., Ma, Q., Tian, W., & Yao, S. (2022). The relationship between physical exercise and prosocial behavior of junior middle school students in post-epidemic period: The chain mediating effect of emotional intelligence and sports learning motivation and gender differences. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Gallego, D., Leon-del-Barco, B., Mendo-Lazaro, S., Leyton-Roman, M., & Gonzalez-Bernal, J. J. (2020). Modeling physical activity, mental health, and prosocial behavior in school-aged children: A gender perspective. Sustainability, 12(11), 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, U., Karlson, K., & Holm, A. (2011). Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 11(3), 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Moreno, C., Musitu Ochoa, G., Cañas Pardo, E., Estevez Lopez, E., & Callejas Jerónimo, J. E. (2021). Relationship between school integration, psychosocial adjustment and cyber-aggression among adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J., & Shao, W. (2022). Influence of sports activities on prosocial behavior of children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. (2023). Peer’s participation in cram school, teenager’s emotional wellbeing and academic performance: How has the “double threat” occurred? Education & Economy, 39(4), 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., & Lu, J. (2023). Influences of junior high school students participating in school physical exercise on negative emotions: Empirical analysis based on CEPS data. Journal of Shenyang Sport University, 42(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., He, X., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Physical activity, parent-child relationships, and adolescent mental health--evidence from the China education panel survey. China Youth Study, 5, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Bu, F., Wang, F., Liu, L., Zhang, S., Wang, G., & Hu, X. (2023). Recent advances on the molecular mechanisms of exercise-induced improvements of cognitive dysfunction. Translational Neurodegeneration, 12(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, M. L. (2002). Havighurst’s developmental tasks, young adolescents, and diversity. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 76(2), 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, N., Pansu, P., Batruch, A., Bressan, M., Bressoux, P., Brown, G., Butera, F., Cherbonnier, A., Darnon, C., Demolliens, M., De Place, A. L., Huguet, P., Jamet, E., Martinez, R., Mazenod, V., Michinov, E., Michinov, N., Poletti, C., Régner, I., … Desrichard, O. (2021). Socio-emotional competencies and school performance in adolescence: What role for school adjustment? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 640661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoi, A. A., Beckmann, J., Mirifar, A., Martinent, G., & Balint, L. (2020). Influence of organized vs non organized physical activity on school adaptation behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 550952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1985). Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. The American Statistician, 39(1), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S., Zahra, S. T., Subhan, S., & Mahmood, Z. (2021). Family communication, prosocial behavior and emotional/behavioral problems in a sample of Pakistani adolescents. The Family Journal, 21(2), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., Silva, E. S., Hallgren, M., Leon, A. P. D., Dunn, A. L., Deslandes, A. C., Fleck, M. P., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2018). Physical activity and incident depression: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(7), 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Gelhaar, T. (2008). Does successful attainment of developmental tasks lead to happiness and success in later developmental tasks? A test of Havighurst’s (1948) theses. Journal of Adolescence, 31(1), 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B., Olds, T., Curtis, R., Dumuid, D., Virgara, R., Watson, A., Szeto, K., O’Connor, E., Ferguson, T., Eglitis, E., Miatke, A., Simpson, C. E. M., & Maher, C. (2023). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(18), 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, J. H., Wright, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2002). A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 20(4), 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhlmann, M., Sassenberg, K., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Belonging mediates effects of student-university fit on well-being, motivation, and dropout intention. Social Psychology, 49(1), 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Pastor, A. M., & Sancho, P. (2020). Perceived social support, school adaptation and adolescents’ subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1597–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G. A., & Lelieveld, G. J. (2022). Moving the self and others to do good: The emotional underpinnings of prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y., Zhao, Y., & Song, H. (2021). Effects of physical exercise on prosocial behavior of junior high school students. Children, 8(12), 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Cheng, F., Guo, B., Wang, Q., & Cheng, X. (2025). The power of confiding: Negative emotional self-disclosurefacilitates peer prosocial behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 57(10), 1762–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Liu, T., Jin, X., & Zhou, C. (2024). Aerobic exercise promotes emotion regulation: A narrative review. Experimental Brain Research, 242(4), 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Liang, J., Chen, J., Dong, W., & Lu, C. (2024). Physical activity and school adaptation among Chinese junior high school students: Chain mediation of resilience and coping styles. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1376233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B., Lei, S., Wu, Y., Chang, I., Zhao, M., & Ju, F. (2025). Cultivating physical literacy and prosocial behavior through basketball: A quasi-experimental study on the teaching personal and social responsibility (TPSR) model. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., Tao, B., Shi, L., Lou, H., Li, H., & Liu, M. (2020). The relationship between extracurricular physical exercise and school adaptation of adolescents: A chain mediating model and gender difference. China Sport Science and Technology, 56(10), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Wu, B., & Wang, F. (2023). Influence of physical exercise on depression of Chinese elderly. China Sport Science and Technology, 59(01), 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., & Gai, X. (2011). Primary and secondary school adjustment theoretical models and reflection. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 3, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. (2023). Can physical exercise reduce Adolescents’Deviant behaviors? Evidence from China education panel survey. Journal of Educational Studies, 19(4), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Sample Size | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Adjustment | 8707 | 26.60 | 4.519 | 9 | 36 |

| Negative Emotions | 8707 | 19.63 | 7.602 | 9 | 45 |

| Prosocial Behavior | 8707 | 11.41 | 2.275 | 3 | 15 |

| Physical Exercise | 8707 | 2.526 | 1.522 | −4.605 | 5.886 |

| Gender | 8558 | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Only child | 8597 | 0.448 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| Own health status | 8647 | 3.869 | 0.933 | 1 | 5 |

| Health education status | 8591 | 0.629 | 0.483 | 0 | 1 |

| Obesity perception | 8650 | 0.376 | 0.484 | 0 | 1 |

| Live in school | 8546 | 0.299 | 0.458 | 0 | 1 |

| Household Economic Status | 8377 | 2.820 | 0.606 | 1 | 5 |

| Father’s education | 8385 | 10.44 | 3.154 | 0 | 19 |

| Mother’s education | 8354 | 9.858 | 3.473 | 0 | 19 |

| Father–child relationship | 8675 | 2.506 | 0.579 | 1 | 3 |

| Mother–child relationship | 8670 | 2.705 | 0.501 | 1 | 3 |

| Parental relationships | 8622 | 0.899 | 0.302 | 0 | 1 |

| Type of school | 8707 | 0.938 | 0.242 | 0 | 1 |

| Ranking of the school | 8707 | 3.984 | 0.839 | 1 | 5 |

| Location of the school | 8520 | 2.340 | 0.790 | 1 | 3 |

| School physical facilities | 8707 | 0.876 | 0.330 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Exercise | 0.616 *** | 0.462 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.357 *** |

| (0.031) | (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.034) | |

| Gender | −1.428 *** | −1.196 *** | −1.160 *** | |

| (0.092) | (0.091) | (0.092) | ||

| Only child | 1.196 *** | 0.500 *** | 0.436 *** | |

| (0.097) | (0.104) | (0.107) | ||

| Own health status | 1.207 *** | 0.898 *** | 0.897 *** | |

| (0.052) | (0.053) | (0.054) | ||

| Health education status | 0.944 *** | 0.819 *** | 0.768 *** | |

| (0.096) | (0.094) | (0.095) | ||

| Obesity perception | −0.430 *** | −0.435 *** | −0.471 *** | |

| (0.096) | (0.093) | (0.095) | ||

| Live in school | −0.839 *** | −0.661 *** | −0.491 *** | |

| (0.106) | (0.109) | (0.120) | ||

| Household Economic Status | 0.501 *** | 0.474 *** | ||

| (0.083) | (0.084) | |||

| Father’s education | 0.093 *** | 0.088 *** | ||

| (0.020) | (0.020) | |||

| Mother’s education | 0.106 *** | 0.099 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.018) | |||

| Father–child relationship | 0.932 *** | 0.953 *** | ||

| (0.093) | (0.094) | |||

| Mother–child relationship | 1.263 *** | 1.246 *** | ||

| (0.106) | (0.107) | |||

| Parental relationships | 0.778 *** | 0.776 *** | ||

| (0.173) | (0.174) | |||

| Type of school | 0.768 *** | |||

| (0.212) | ||||

| Ranking of the school | 0.095 | |||

| (0.061) | ||||

| Location of the school | 0.137 | |||

| (0.074) | ||||

| School physical facilities | −0.193 | |||

| (0.131) | ||||

| Constant | 25.044 *** | 20.820 *** | 12.681 *** | 11.597 *** |

| (0.092) | (0.236) | (0.391) | (0.498) | |

| Observations | 8707.000 | 8107.000 | 7539.000 | 7380.000 |

| R2 | 0.043 | 0.176 | 0.254 | 0.257 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel B | Results of phase II | |||

| Physical Exercise | 2.858 *** | 1.954 *** | 1.348 *** | 1.354 *** |

| (0.158) | (0.153) | (0.159) | (0.162) | |

| Panel A | Results of phase I | |||

| School-level sports participation rates (other than individual) | 0.854 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.750 *** | 0.752 *** |

| (0.036) | (0.119) | (0.041) | (0.042) | |

| Individual characteristics | Control | Control | Control | |

| Family characteristics | Control | Control | ||

| School characteristics | Control | |||

| Constant | 0.369 *** | −0.340 ** | −0.919 *** | −0.891 *** |

| (0.091) | (0.118) | (0.160) | (0.242) | |

| Observations | 8707 | 8107 | 7539 | 7380 |

| Minimum eigenstatistic value | 577.48 | 101.61 | 53.13 | 41.34 |

| Matching Method | T | C | ATT | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest neighbor matching | 27.634 | 26.596 | 1.037 | 0.120 |

| Radius matching | 27.634 | 26.590 | 1.044 | 0.109 |

| Kernel matching | 27.624 | 26.579 | 1.055 | 0.109 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | SA | PB | SA | SA | |

| Physical exercise | −0.169 ** | 0.331 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.233 *** | 0.216 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.030) | (0.017) | (0.030) | (0.030) | |

| Negative emotions | −0.152 *** | −0.143 *** | |||

| (0.006) | (0.006) | ||||

| Prosocial behavior | 0.509 *** | 0.480 *** | |||

| (0.021) | (0.020) | ||||

| Individual characteristics | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Family characteristics | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| School characteristics | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | 35.476 | 17.610 | 6.673 | 8.834 | 14.099 |

| (0.919) | (0.536) | (0.273) | (0.507) | (0.538) | |

| Observations | 7023 | 7023 | 7023 | 7023 | 7023 |

| R2 | 0.123 | 0.312 | 0.126 | 0.312 | 0.362 |

| Coefficient | SE | Percentage of Relative Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.357 | 0.029 | 100% |

| Direct effect | 0.216 | 0.030 | 60.50% |

| Total indirect effect | 0.141 | 0.013 | 39.50% |

| Indirect effect 1 (Negative emotions) | 0.024 | 0.008 | 6.73% |

| Indirect effect 2 (Prosocial behavior) | 0.117 | 0.010 | 32.77% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, S.; Chen, H.; Lu, T.; Tao, B.; Yan, J. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment and Path Analysis—Evidence from the China Education Panel Survey. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121602

Tang S, Chen H, Lu T, Tao B, Yan J. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment and Path Analysis—Evidence from the China Education Panel Survey. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121602

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Shaohua, Hanwen Chen, Tianci Lu, Baole Tao, and Jun Yan. 2025. "The Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment and Path Analysis—Evidence from the China Education Panel Survey" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121602

APA StyleTang, S., Chen, H., Lu, T., Tao, B., & Yan, J. (2025). The Effects of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ School Adjustment and Path Analysis—Evidence from the China Education Panel Survey. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121602