Exploring How a Therapy Dog Intervention in a Tier 3 Classroom Influences Mental Health Components of Well-Being: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. AAIs in Education

1.2. Mental Health Components of Well-Being

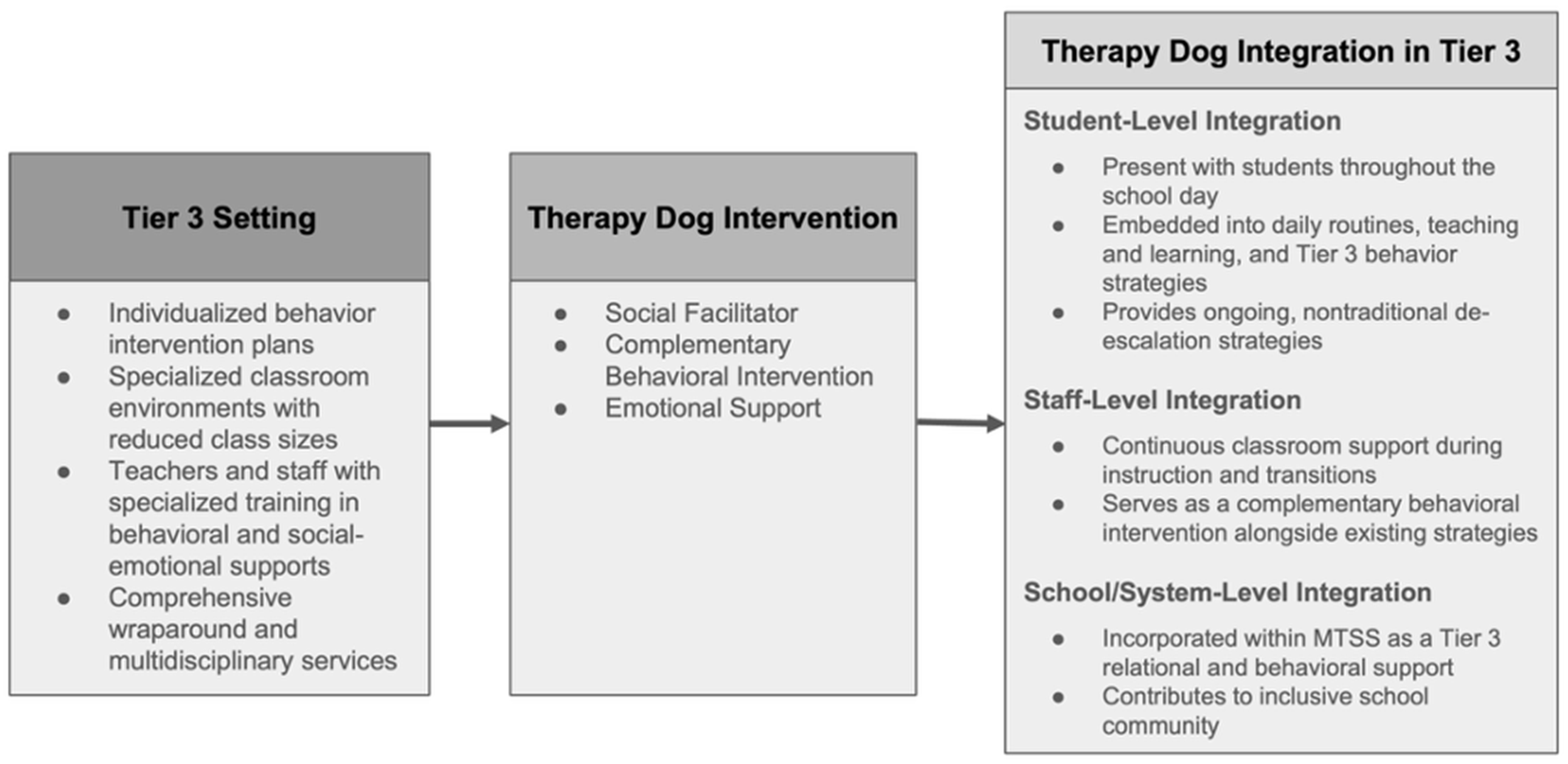

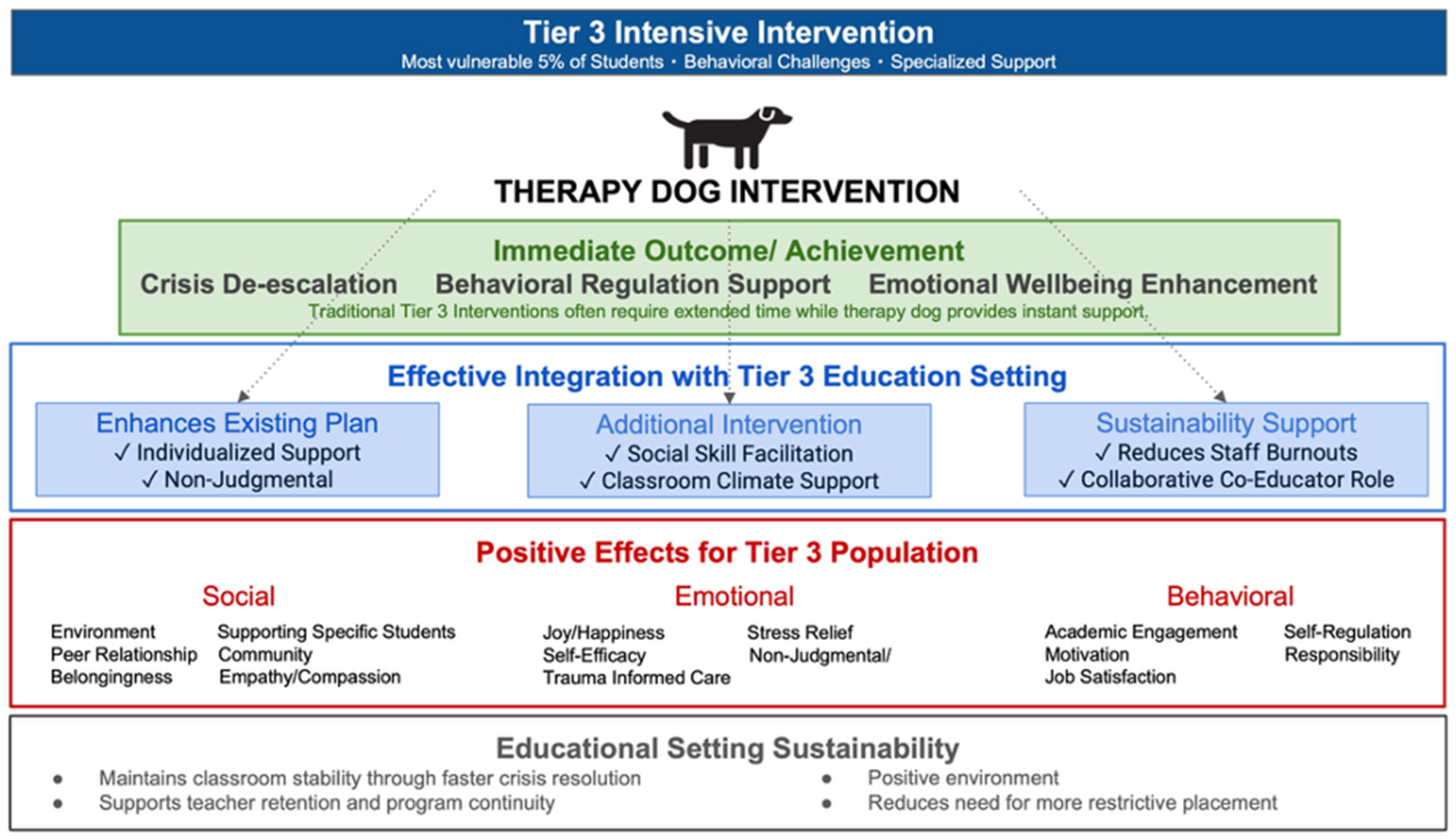

1.3. Tiered Support Models and Intensive Intervention Contexts

1.4. The Present Case Study

- How do therapy dog interventions influence mental health components of well-being, social, emotional, and behavioral functioning, in a Tier 3 intervention classroom?

- How can therapy dog interventions be effectively integrated within existing Tier 3 behavioral management systems to optimize student outcomes?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Therapy Dog Program

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Semi-Structured Interview

2.5.2. Classroom Observations and Feedback

2.5.3. Field Notes

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Social Well-Being

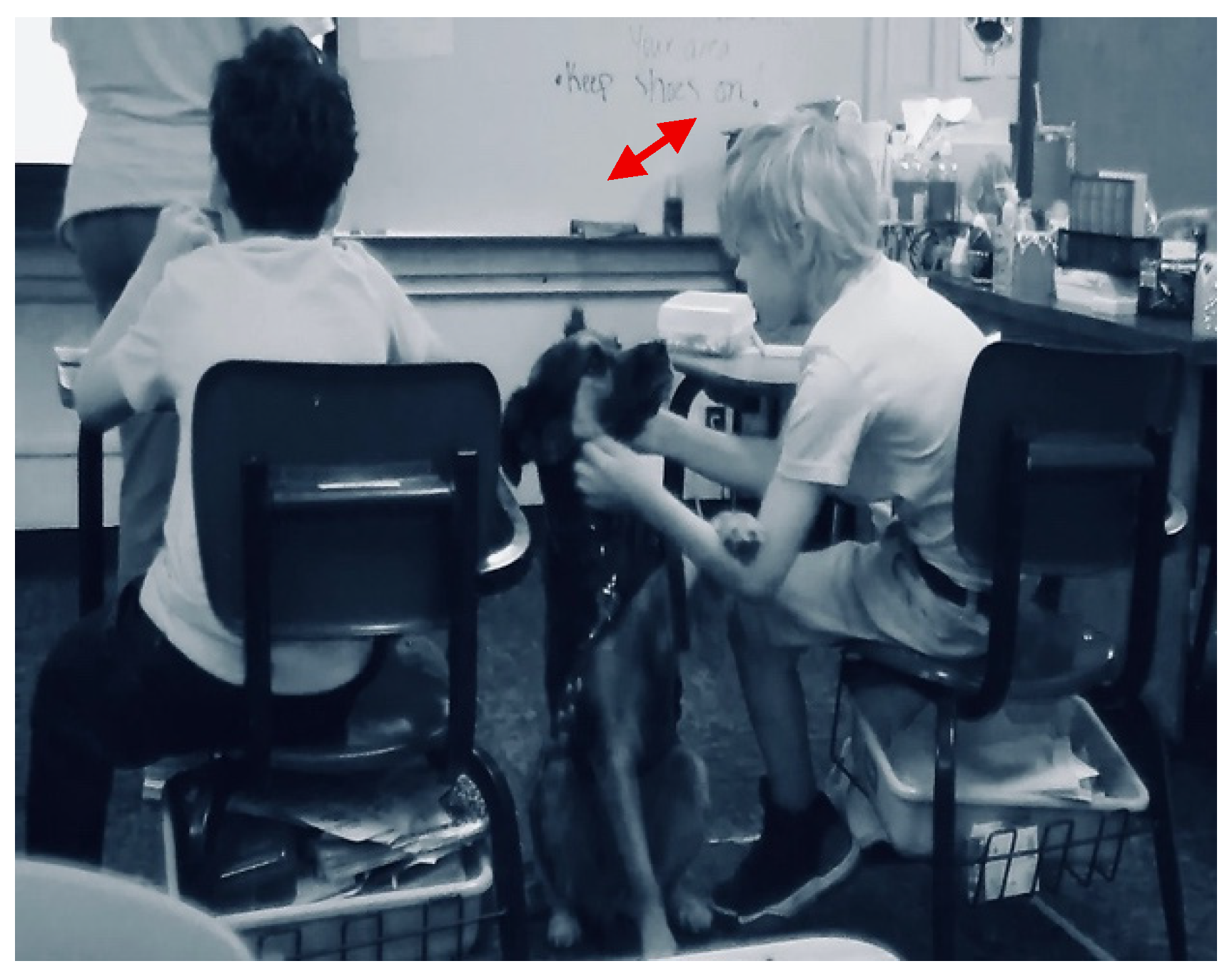

3.1.1. Environment

3.1.2. Peer Relationships

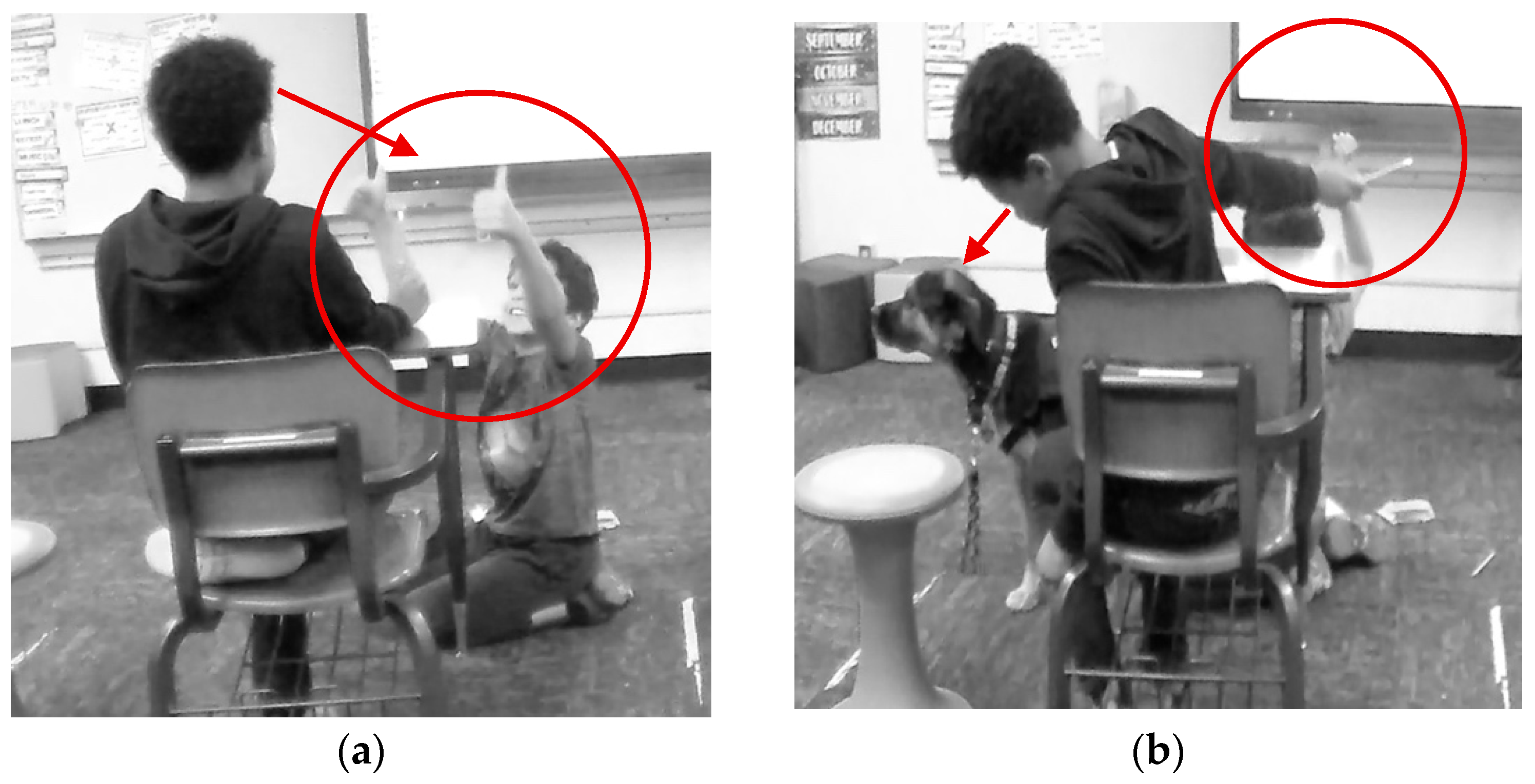

When you realize that these kids don’t always necessarily build each other up…it’s really awesome when they do that. And lately…they are starting to help each other and, hey, I got this. This is why. And I kind of let that go because that’s the relationships they need to learn how to build. And honestly, the Danielson model that we’re evaluated with encourages that as well, is building the kids up to a point where they can take it and run and help each other and not always get input from us.

3.1.3. Supporting Specific Students

Sometimes when I get sad and go off to the corner….She [Muffin] kind of knows when you are sad. She’ll come up to you and lay right next to you. And then you pet her and it’s kind of nice because she kind of knows.

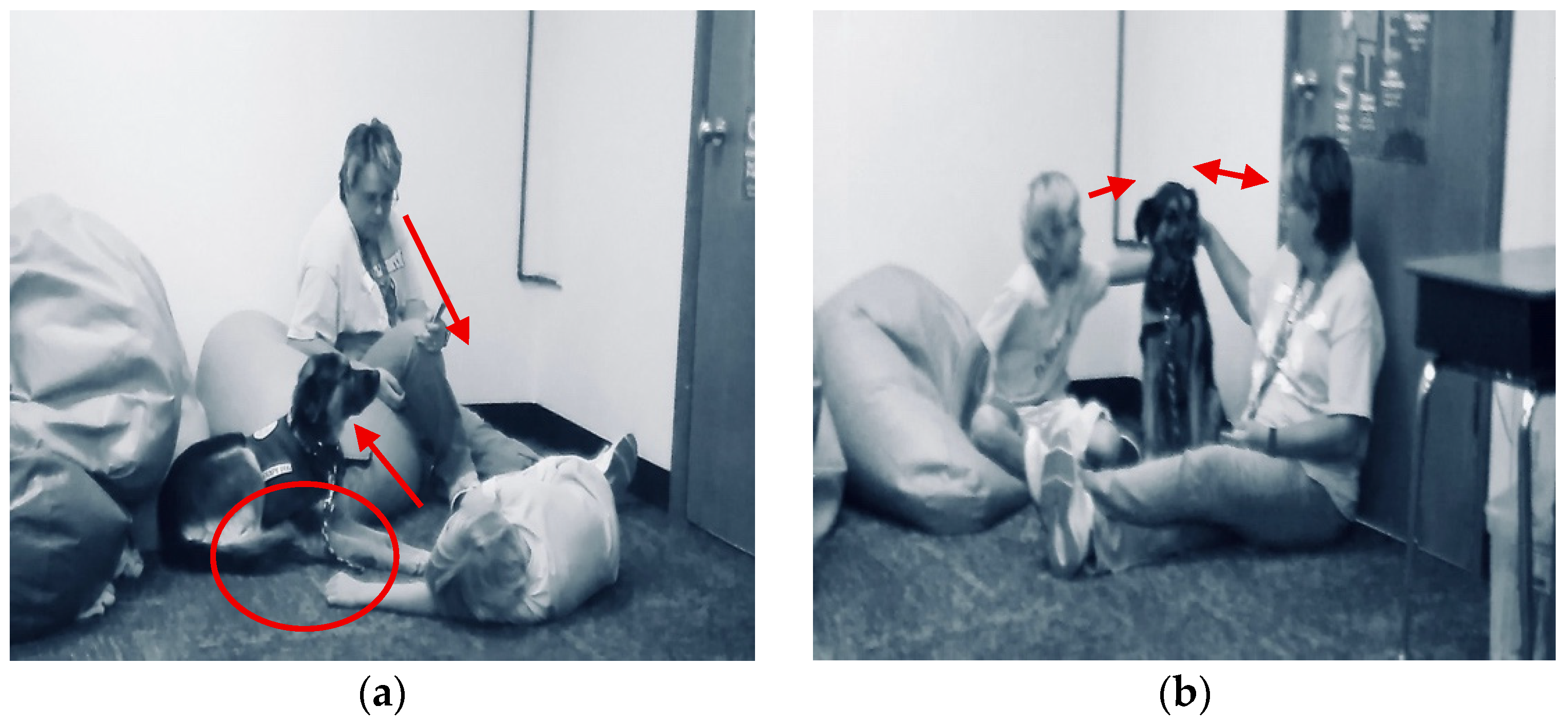

The above statement demonstrates that Muffin and Mrs. Gaddis provide personalized support based on their knowledge of the individual needs of each student.She [Muffin, therapy dog] helps calm him just by sitting there and she sits and waits. And then the second that he starts engaging, then she becomes more engaged in the situation. And I didn’t ever teach her that, but she seems to understand what the kids need and it’s really kind of cool to watch. And with Logan, that’s why I came back too, and I sat with him for a while. I was like, “Hey, I really need help with these answers. If you could give me the answer, then I can tell if you are getting it for sure or not?” And so, since he could sit back there with both of us and he could give answers, but it wasn’t disrupting the rest of the class, it works for him. So, with him, I have to approach him on several different levels to get him to come down, but she helps quite a bit just because of her calming, lying next to him. She’ll put her foot on him, “Hey, pet my tummy, or whatever.”

3.1.4. Community

She [Muffin, therapy dog] goes to every staff meeting with us. And I think one day I didn’t take her, and I had to come back to my room to get her because there were a lot of very disappointed people. So, I think she’s just as much a part of the staff and what’s going on here as she is with the students.

The students at Muffin’s school look forward to her consistent presence in their classroom and school.We have all 1, 2, 3, 4 classrooms all in a row, generally what we do is leave the two doors open and she’ll [Muffin, therapy dog] go between the two to four classrooms and greet the kids. And actually today, our fifth and sixth grade classroom, the kids came over at the end of the day, they were testing and they were like, “Muffin didn’t come in today.” And I was like, “Yeah, well the door was shut because you guys are testing.” And then, the rest of the kids, kindergarten and then first, second grades next to us as well. Sometimes she’s earned like, “Hey, I need a break. Can I please go out? Can I take Muffin?” And that motivates a couple of the kids.

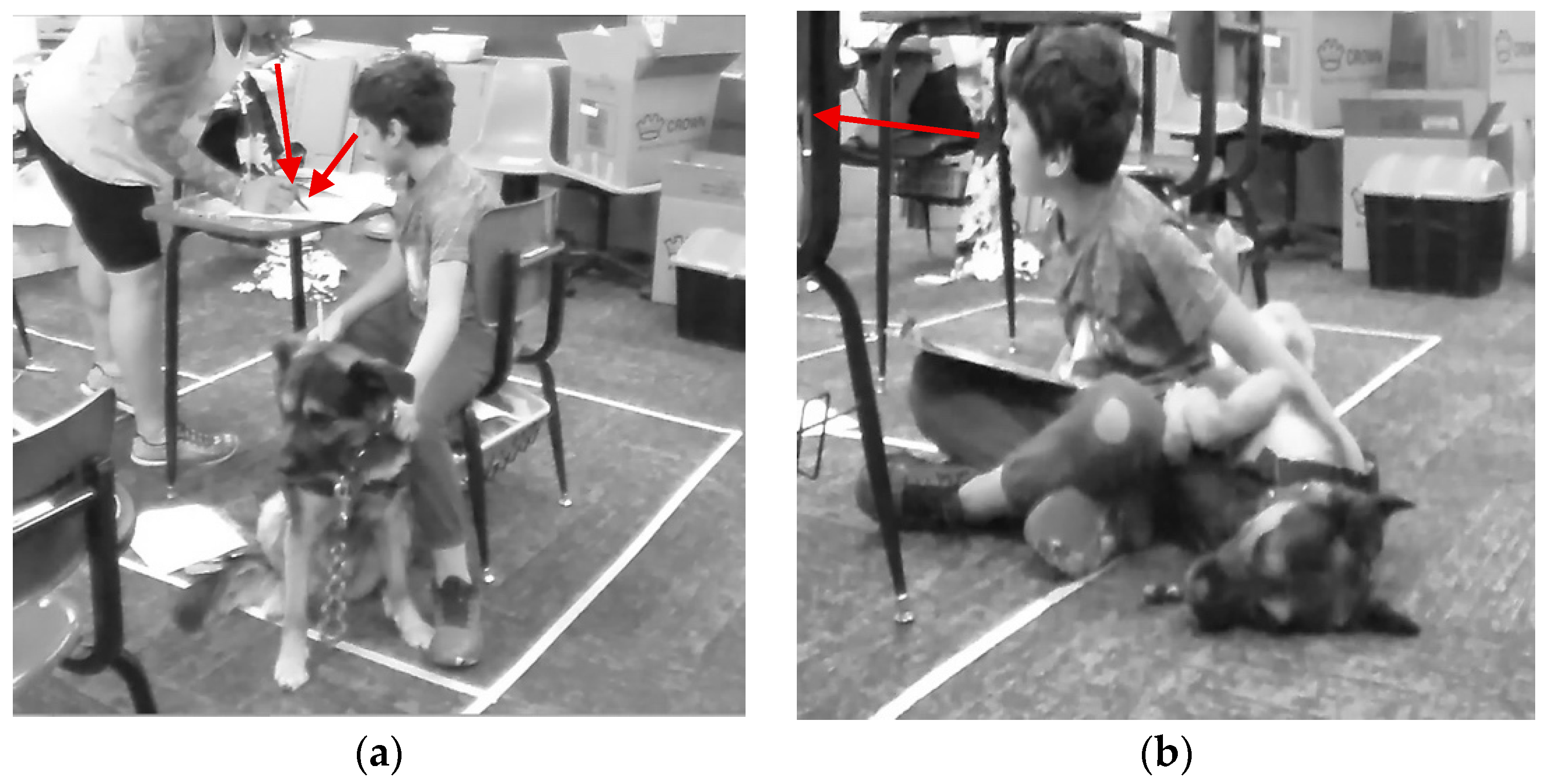

3.1.5. Belongingness

Muffin is a member of the class and serves like a co-educator in her ability to sense when a student needs support and provide that comfort to the student.Helps me immensely, because she [Muffin, therapy dog] knows our kids. She knows and has the ability to comfort our kids. If one of our kids is dysregulated, she knows before we do sometimes. And she picks up on it really easily. And it’s such a comfort that they can just calm down and hang out with her. And she helps regulate the kid back to what they are supposed to be doing. As staff, it is significantly helpful.

3.1.6. Empathy/Compassion

We incorporate that [social emotional learning] in our learning every single day because our kids, especially with having behavior disorders, they’re told all the time, “You are bad. You are this, you are that.” And so, they get a lot of that negative input. So, when they come into this program, we do social emotional learning five days a week, every morning we do it. And it’s funny because Muffin [therapy dog] now joins our circle and the kids will include her like, “Oh, well if we did this, she wouldn’t like that.” It’s been good because animals’ emotions are very much on their sleeve because they’re not going to hide it. They don’t know that they should or shouldn’t. So, I think that that does help the kids a little bit to learn forgiveness, how to react.

I think that seeing is believing, but also just to understand how much it affects the kids and how much they look forward to the interaction with the dog and how quickly it does deescalate situations that are going in a wrong direction. I think being an animal person to begin with, I just think that’s so important for kids to learn and to understand that it’s okay. It’s okay to have bad feelings, and it’s okay to calm down from those feelings.

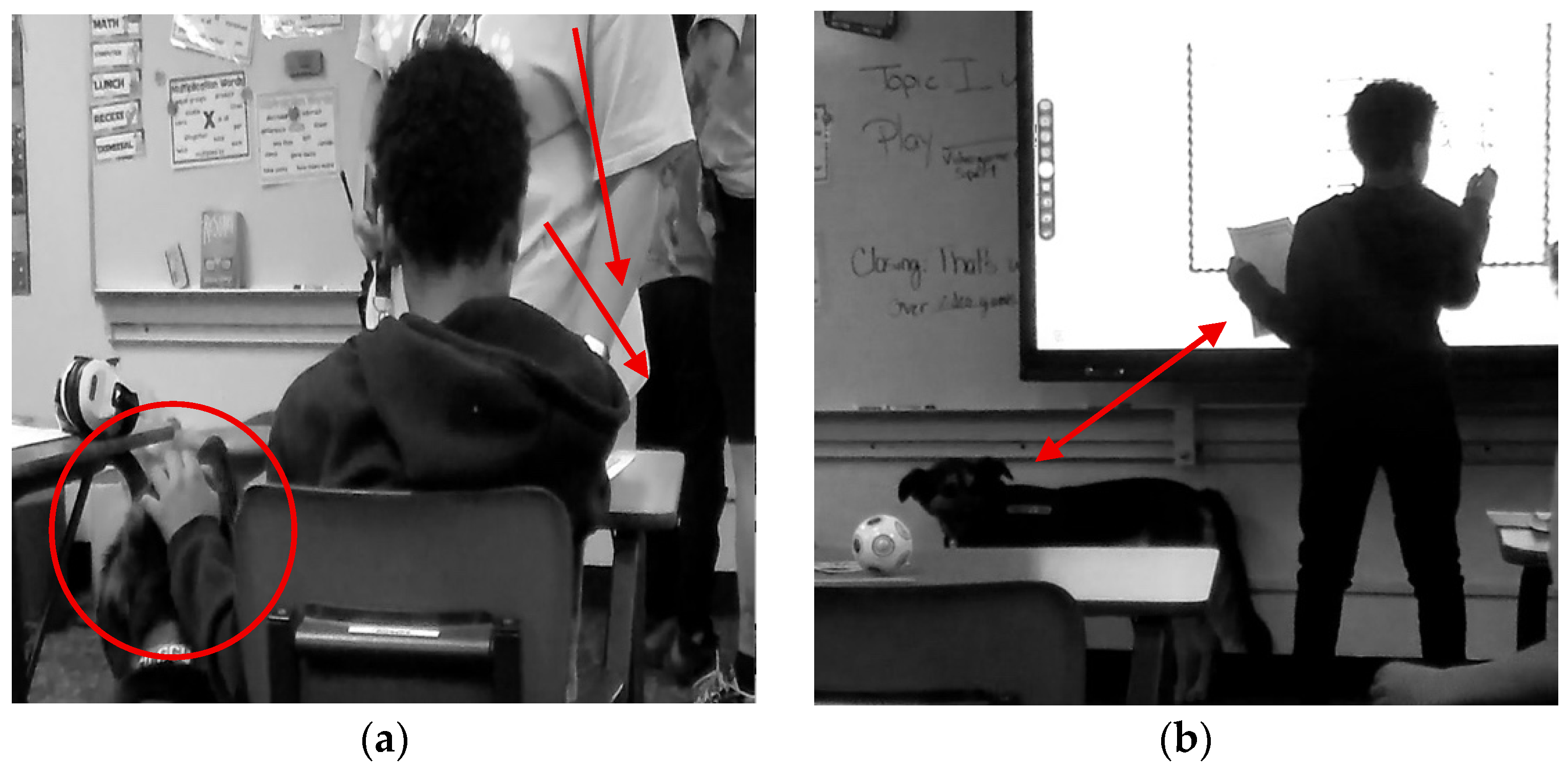

3.2. Behavioral Well-Being

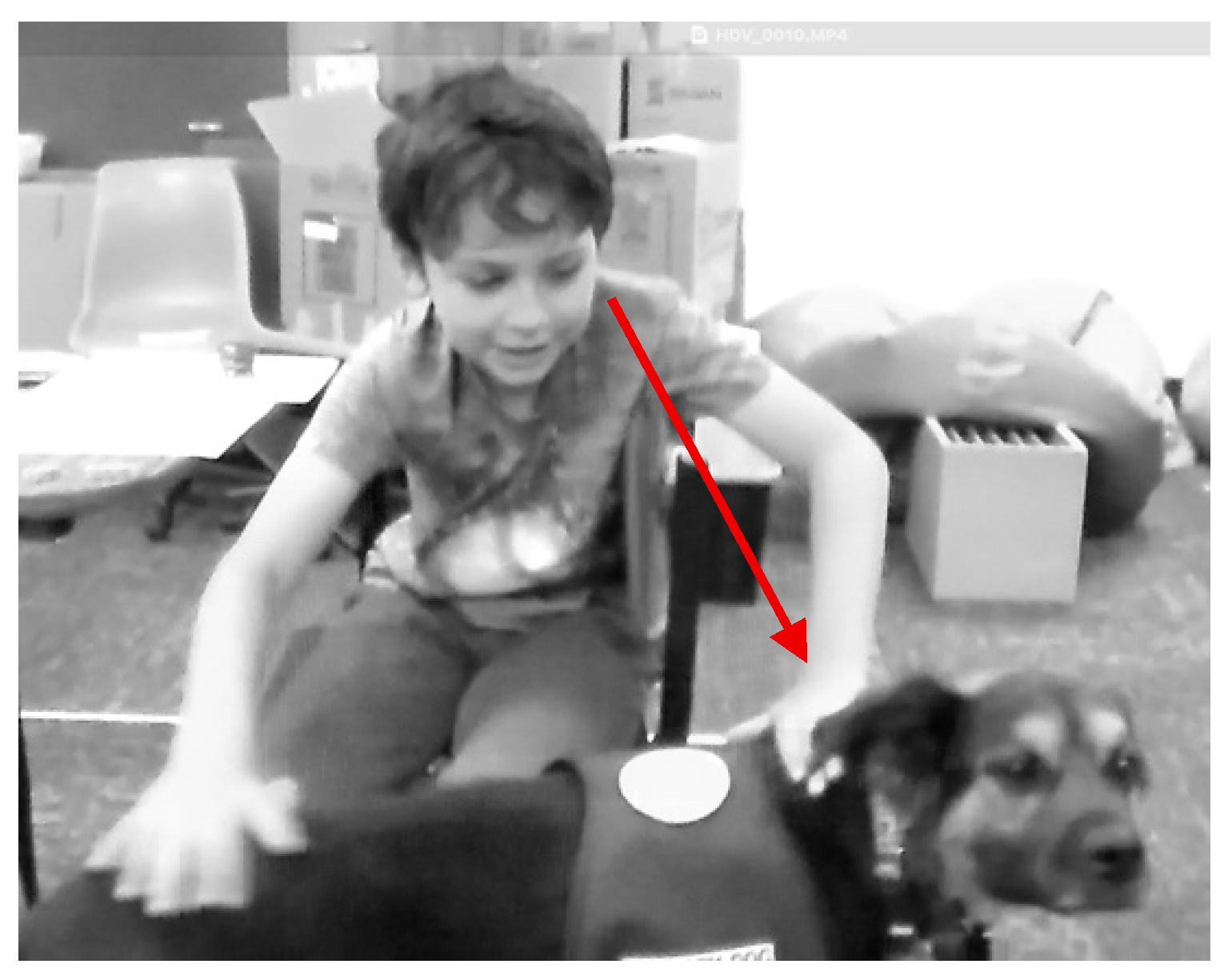

3.2.1. Academic Engagement

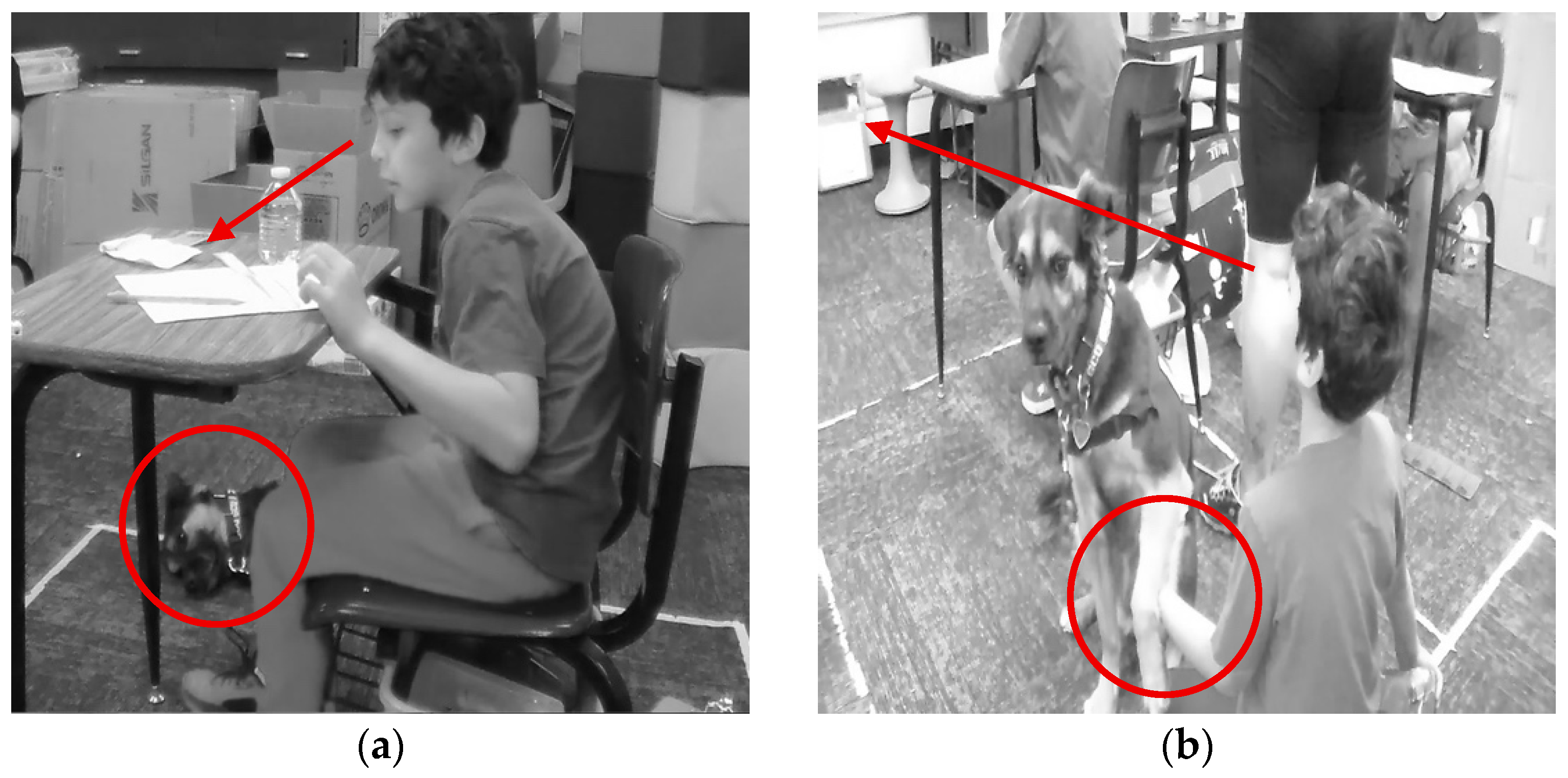

Figure 5 shows Logan taking a brief break during math instruction to pet Muffin before returning to the whole group math activity. Logan gently pets Muffin with both hands, and they gaze at each other for a bit and Logan refocuses on his math work.Like when we are working and we don’t really know the answer, she [therapy dog] will walk up to us and we can pet her. I pet her and it helps reset my mind and I can figure out the answers and stuff…It has been working for me, and it can help us.

3.2.2. Self-Regulation

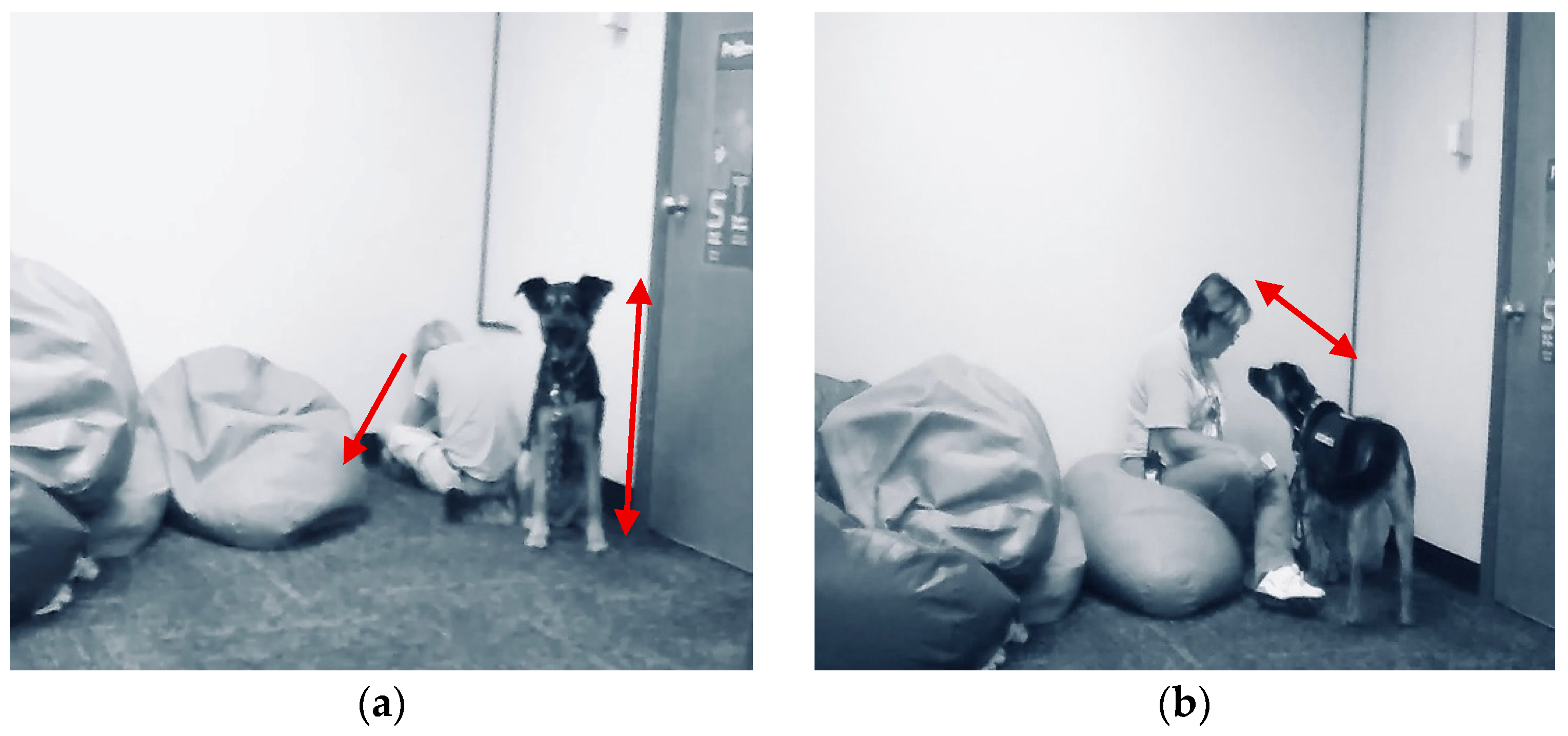

The presence of Muffin combined with the structure and strategies already in place in the classroom have led to students regulating their emotions quicker and having a non-judgmental confidant that they can talk to when working on regulating their emotions.Prior to having her [Muffin, therapy dog], I feel like there was a lot more negotiating with the kids on trying to get behaviors to come down. And sometimes it would take me 45 minute, an hour, all day depending on how far they escalated. But I feel the difference with having Muffin here is we can de-escalate it a lot quicker. It doesn’t go as high. It doesn’t mean that all behaviors are gone because we still have behaviors. But I think between the structure that I have in my classroom and then having her as a tool, it helps us de-escalate a lot quicker with the kids and give them options that they like and that they can calm down and not feel like anyone’s judging them.

When he [student] gets upset, he kicks things, and he’ll hit himself or scratch himself…Muffin will just walk over and sit next to him. And one day, he was kicking his leg on his chair, and I was sitting here watching it because I was in a little bit of disbelief. She walked over, sat next to him for a minute, he kept kicking the chair. She actually put her head down where he was kicking, and I thought, “Okay, this is not, I don’t know about this.” And he’s very animal oriented himself. He’s one of the ones that was really looking forward to the dog. He stopped kicking, all of a sudden, his hand came down, he started petting her. It calmed the situation in less than a minute.

3.2.3. Motivation

The above quote aligns with the presence of Muffin having a positive impact on the classroom environment and motivating students to want to learn and spend time with her.They’re [students] always like, “Can she [Muffin, therapy dog] sit next to me? Can she sit?” And I’m like, “Guys, first off, there’s only five of us, so she can sit next to all of us.” But it’s kind of, yeah, they want to make sure that they all have a little piece of her, of time with her, and that does motivate them to learn. As long as you’re weaving that piece into your classroom.

3.2.4. Responsibility

The above quote demonstrates that students are being more responsible in how they engage with describing their social and emotional behaviors and how they complete tasks in the classroom due to the presence of Muffin.What I’ve noticed is the kids, before when they would do those social emotional questionnaires, they would just click, click, click, click, click. Now, they actually read it. So, they actually, sometimes they’ll ask me, “What does this mean?” And then, I have to explain it to them, but I feel like they’re actually taking the time to think about it more than they did in the past, which is interesting to me because you wouldn’t think that a dog would make any bit of difference there.

3.2.5. Job Satisfaction

Mrs. Gaddis explained how Muffin has supported students with engagement, motivation, and regulating emotions. In addition, she described how good Muffin is at her job and how grateful she is that they are able to work together as a handler and therapy dog team.It benefits me in a lot more ways than I ever thought. For one, it helps me calm outbursts a little bit quicker because you can, “Hey, do you want to go for a walk? Do you want to take Muffin [therapy dog]?” You can’t kind of get that disengagement because you can bring them down…I mean, she helps all over the place. I can’t even think of everything that she does. But I noticed the kids, even the kids that don’t know her yet that are coming into our program next year from another site, they’re already like, “Hey, can we get a picture of Muffin?”

Yep. She’s [Muffin, therapy dog] really good at it. Like I said, she was meant to do this job and for some reason she came to me and thank God I’ve been able to do that with her because she’s really good at what she does.

3.3. Emotional Well-Being

3.3.1. Joy/Happiness

I should probably just do a video of the morning when she knows it’s her morning. She gets so excited about coming to school. It’s a high-pitched yappy yapperton and she runs around the yard like a maniac. I mean, it kind of takes us a few minutes to get to the car because she’s so overexcited about it. She also, once we’re in the classroom, I’ve never taught her how to read time, but apparently, she knows it because she knows when it’s time to go up to get the kids off the bus. She is on me like, “Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go.” So, she very much likes what she does, and she tries, like yesterday in the morning she tried everything to get to go to school with me and I was like, “It is not your day, ma’am…You just have that feeling that she knows what her job is.

3.3.2. Stress Relief

3.3.3. Self-Efficacy

He [student] just lacks confidence sometimes. And yesterday it was like, hey, I know you know this. So, then we were just kind of, I tell him, “This is our secret. It’s only between us.” And so then, he’ll tell me, “Okay, I think that’s this amount of money.” And I’m like, “Yeah, that’s great.” He was, because sometimes that’s just all they need. They don’t want to call out in front of everyone, but they do know the topic, they just worry that they don’t…She’ll [therapy dog] sit with him a lot as well during those kinds of things.

3.3.4. Non-Judgmental/Trauma Informed Care

He’s my go-for-a-walk kid. He’s always wanting, he usually likes to remove himself from the situation, calm down and then come back. So yeah, we look at all of them as individuals. And when Muffin [therapy dog] is not here, they all have different things that they like to do.

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAI | Animal-assisted interventions |

| MTSS | Multi-tiered systems of support |

| SEL | Social emotional learning |

References

- Anderson, K. L., & Olson, M. R. (2006). The value of a dog in a classroom of children with severe emotional disorders. Anthrozoös, 19(1), 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Beetz, A., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human–animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackett, M. A., Reyes, M. R., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., & Salovey, P. (2012). Assessing teachers’ beliefs about social and emotional learning. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(3), 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, C. E., Baetz, C. L., Horwitz, S. M., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2017). Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: A systematic review of definitions and core components. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(6), 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., & Resnick, B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelsford, V. L., Meints, K., Gee, N. R., & Pfeffer, K. (2017). Animal-assisted interventions in the classroom—A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design (1st ed.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B. G., Buysse, V., Klingner, J., Landrum, T. J., McWilliam, R. A., Tankersley, M., & Test, D. W. (2015). CEC’s standards for classifying the evidence base of practices in special education. Remedial and Special Education, 36(4), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2008). Evidence-based practices in special education: Some practical considerations. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreer, B., & Gouasé, N. (2021). Interventions fostering well-being of schoolteachers: A review of research. Oxford Review of Education, 48(5), 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrand, K. M., & Jung, J. Y. (2025a). The impact of therapy dogs on well-being and teaching and learning in PK-12 education: Stakeholder perspectives. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrand, K. M., & Jung, J. Y. (2025b). Therapy dogs district-wide: Mental health and well-being influences in PK-12 education. Education Sciences, 15(7), 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A. H. (2019). Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Foundations and guidelines for animal-assisted interventions (4th ed.). Academic Press. Available online: https://www.educate.elsevier.com/book/details/9780128153956 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Freeman, R., Eber, L., Anderson, C., Irvin, L., Horner, R., Bounds, M., & Dunlap, G. (2006). Building inclusive school cultures using school-wide positive behavior support: Designing effective individual support systems for students with significant disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31(1), 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, F. M. (2016). Social skills assessment and intervention for children and youth. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(3), 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueldner, B. A., Feuerborn, L. L., Merrell, K. W., & Weissberg, R. P. (2020). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Promoting mental health and academic success (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Available online: https://www.guilford.com/excerpts/gueldner_ch1.pdf?t=1 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hall, S. S., Gee, N. R., & Mills, D. S. (2016). Children reading to dogs: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE, 11(2), e0149759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, N. M., & Binfet, J. T. (2022). Exploring children’s perceptions of an after-school canine-assisted social and emotional learning program: A case study. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 36(1), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain and Education, 1(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalongo, M. R. (2015). An attachment perspective on the child–dog bond: Interdisciplinary and international research findings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(5), 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., Cantwell, E. D., Common, E. A., Royer, D. J., Leko, M. M., Schatschneider, C., Menzies, H. M., Buckman, M. M., & Allen, G. E. (2019). Predictive validity of Student Risk Screening Scale—Internalizing and Externalizing (SRSS-IE) scores in elementary schools. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 27(4), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggin, D. M., Pustejovsky, J. E., & Johnson, A. H. (2017). A meta-analysis of school-based group contingency interventions for students with challenging behavior: An update. Remedial and Special Education, 38(6), 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, C. K., & Elliott, S. N. (2002). Children’s social behaviors as predictors of academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitz, J., Brack, F., Hertel, S., Krull, J., Stephan, H., Hennemann, T., & Hanisch, C. (2023). Multi-tiered systems of support with focus on behavioral modification in elementary schools: A systematic review. Heliyon, 9(6), e17506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Haire, M. E. (2013). Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., & Hershfeldt, P. A. (2012). Teacher-and school-level predictors of teacher efficacy and burnout: Identifying potential areas for support. Journal of School Psychology, 50(1), 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T. M., Gage, N., Hirn, R., & Han, H. (2019). Teacher and student race as a predictor for negative feedback during instruction. School Psychology Quarterly, 34(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1954-05139-000 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: Integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality, 17(4), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2020). Sustaining and scaling positive behavioral interventions and supports: Implementation drivers, outcomes, and considerations. Exceptional Children, 86(2), 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., Abrams, L., & Vo, A. (2010). Improving interactions between teachers and young children with problem behavior: A strengths-based approach. Exceptionality, 18(2), 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, W. M. (1997). Application of a case study methodology. The Qualitative Report, 3(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. MIT Press. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-98256-000 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. (2021). Supporting child and student social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health needs. Washington, DC. Available online: https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5d3725188825e071f1670246/61705139ed33836fdb42749a_supporting_child_student_social_emotional_behavioral_mental_health.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Walker, H. M., Ramsey, E., & Gresham, F. M. (2004). Antisocial behavior in school: Evidence-based practices (2nd ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed389133 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wiedermann, C. J., Barbieri, V., Plagg, B., Marino, P., Piccoliori, G., & Engl, A. (2023). Fortifying the foundations: A comprehensive approach to enhancing mental health support in educational policies amidst crises. Healthcare, 11(10), 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zins, J. E., Bloodworth, M. R., Weissberg, R. P., & Walberg, H. J. (2007). The scientific base linking social and emotional learning to school success. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 17(2–3), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Theme | Sub-Theme | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Social Well-Being | Environment | Observations describing positive impacts on the physical and social learning environment. |

| Peer Relationships | Interactions or social connections between students or between students and staff. | |

| Supporting Specific Students | Individualized support strategies or interventions targeting particular student needs. | |

| Community | Behaviors or statements indicating membership and integration within classroom or school groups. | |

| Belongingness | Expressions demonstrating sense of acceptance, inclusion, or being valued as a member. | |

| Empathy/Compassion | Manifestations of understanding, care, or emotional support toward others. | |

| Behavioral Well-Being | Academic Engagement | Active participation, attention, or involvement in educational tasks and activities. |

| Self-Regulation | Management of emotions, behaviors, or responses to maintain appropriate functioning. | |

| Motivation | Drive, interest, or willingness to participate in activities or pursue goals. | |

| Responsibility | Demonstration of accountability, thoughtful decision-making, or ownership of actions | |

| Job Satisfaction | Professional fulfillment, effectiveness, or positive attitudes toward work responsibilities. | |

| Emotional Well-Being | Joy/Happiness | Observable expressions of positive emotions, contentment, or pleasure. |

| Stress Relief | Reduction in tension, anxiety, or distress; increased comfort or relaxation. | |

| Self-Efficacy | Confidence in personal abilities to perform tasks or achieve desired outcomes. | |

| Non-Judgmental/Trauma Informed Care | Provision of unconditional acceptance and individualized support sensitive to past experiences. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farrand, K.M.; Jung, J.Y. Exploring How a Therapy Dog Intervention in a Tier 3 Classroom Influences Mental Health Components of Well-Being: A Case Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111585

Farrand KM, Jung JY. Exploring How a Therapy Dog Intervention in a Tier 3 Classroom Influences Mental Health Components of Well-Being: A Case Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111585

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarrand, Kathleen M., and Jae Young Jung. 2025. "Exploring How a Therapy Dog Intervention in a Tier 3 Classroom Influences Mental Health Components of Well-Being: A Case Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111585

APA StyleFarrand, K. M., & Jung, J. Y. (2025). Exploring How a Therapy Dog Intervention in a Tier 3 Classroom Influences Mental Health Components of Well-Being: A Case Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111585