Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Analysis of Employment Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

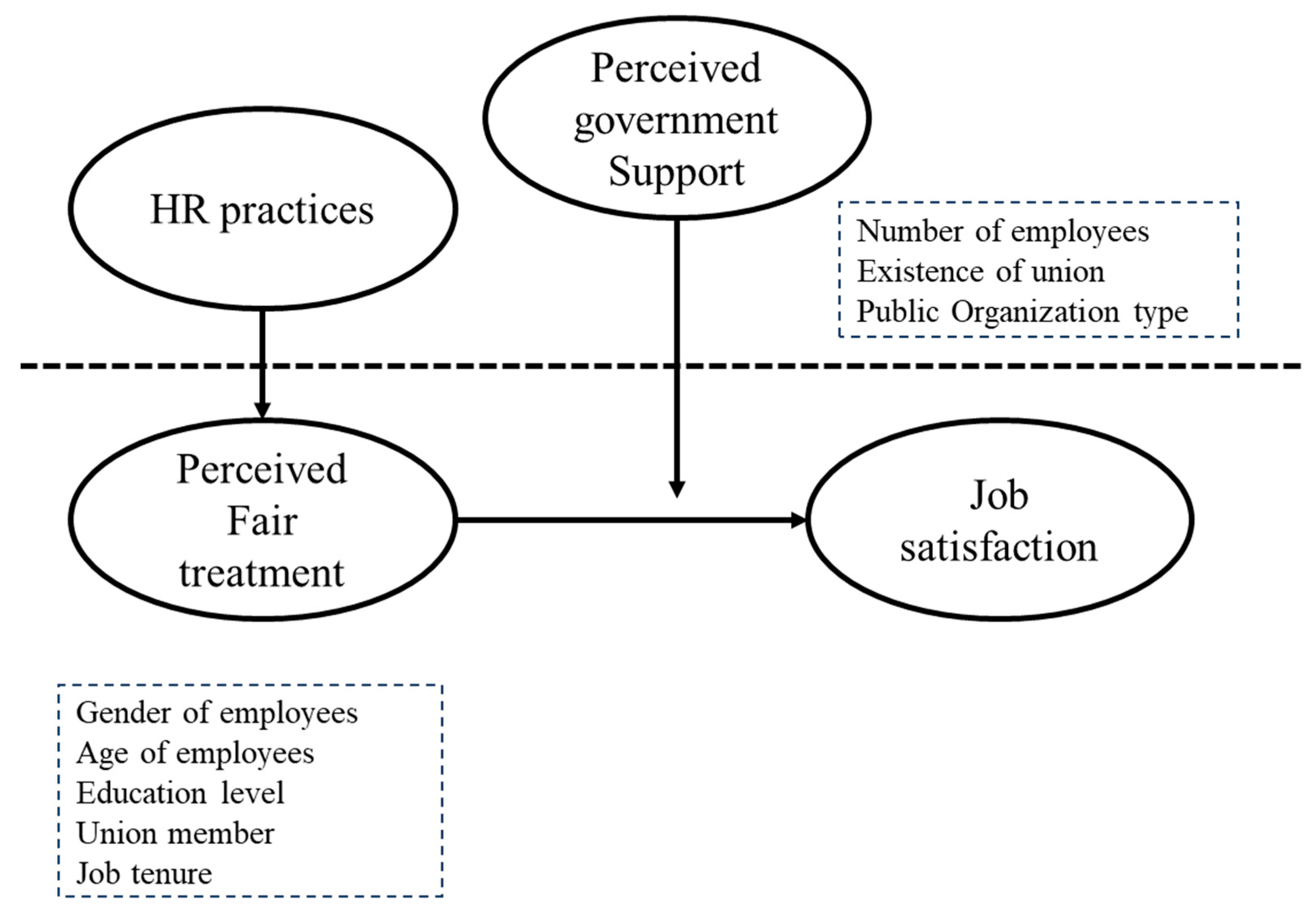

2. Korean Context

3. Theory Development and Hypotheses

3.1. Organizational Justice Theory and Employment Transition

3.2. Perceived Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction

3.3. HR Practices and Perceived Fair Treatment

3.4. Moderation Effects of Perceived Government Support

4. Methods

4.1. Research Setting, Sample, and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Perceived Fair Treatment

4.2.2. Job Satisfaction

4.2.3. HR Practice

4.2.4. Perceived Government Support

4.2.5. Control Variables

4.3. Data Analyses

Data Analytical Strategy

5. Results

5.1. Respondent Characteristics

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amar, H., Talreja, K., Shaikh, S., Bhutto, S. A., & Mangi, Q. A. (2021). Organizational justice intervention between employee silence and work engagement: Study from employee perspective. Ilkogretim Online, 20(4), 460–468. [Google Scholar]

- An, S. M., & Lee, J. W. (2021). Nonstandard employment and organizational effectiveness: The transition from nonstandard to standard employment in South Korea. Korea Observer, 52(2), 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadullah, M. A., Akram, A., Imran, H., & Arain, G. A. (2017). When and which employees feel obliged: A personality perspective of how organizational identification develops. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 33(2), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43–55). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. J. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, N., & Zelazny, L. (2022). Measuring general job satisfaction: Which is more construct valid—Global scales or facet-composite scales? Journal of Business & Psychology, 37(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., & Jin, Y. H. (2014). The effects of organizational justice on organizational citizenship behavior in the chinese context: The mediating effects of social exchange relationship. Public Personnel Management, 43(3), 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak-Hai, L., & Rabenu, E. (2018). The new era workplace relationships: Is social exchange theory still relevant? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 11(3), 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A., Hussain, I. A., Ahmad, N., & Singh, J. S. K. (2021). Organisation justice towards’ employees voluntary turnover: A perspective of SMEs in Malaysia. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 11(2), 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A., Greenberg, J., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2005). What is organizational justice? A historical overview. In J. A. Colquitt, J. Greenberg, & C. P. Zapata-Phelan (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., Noe, R. A., & Jackson, C. L. (2002). Justice in teams: Antecedents and consequences of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 55(1), 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D., & Stouten, J. (2005). When does giving voice or not matter? Procedural fairness effects as a function of closeness of reference points. Current Psychology, 24(3), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Delery, J. E., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). The strategic management of people in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and extension. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 165–197. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Diekmann, K. A., Barsness, Z. I., & Sondak, H. (2004). Uncertainty, fairness perceptions, and job satisfaction: A field study. Social Justice Research, 17(3), 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drache, D., LeMesurier, A., & Noiseux, Y. (2015, March 19). Non-standard employment, the jobs crisis and precarity: A report on the structural transformation of the world of work. The jobs crisis and precarity: A report on the structural transformation of the world of work. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2581041 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Duane, P. S., & Schultz, S. E. (2020). Psychology and work today (10th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Durazzi, N., Fleckenstein, T., & Lee, S. C. (2018). Social solidarity for all? Trade union strategies, labor market dualization, and the welfare state in Italy and South Korea. Politics & Society, 46(2), 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., & Enders, J. (2007). Support from the top: Supervisors’ perceived organizational support as a moderator of leader-member exchange to satisfaction and performance relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farndale, E., & Kelliher, C. (2013). Implementing performance appraisal: Exploring the employee experience. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. B., & Foa, U. G. (1980). Resource theory: Interpersonal behavior as exchange. In Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 77–94). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, R., & Konovsky, M. A. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 32(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S., Restubog, S. L. D., & Bednall, T. (2012). How employee perceptions of HR policy and practice influence discretionary work effort and co-worker assistance: Evidence from two organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(20), 4193–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahan, P. (2012). ‘Voice Within Voice’: Members’ voice responses to dissatisfaction with their Union. Industrial Relations, 51(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, G. C., & Desa, N. M. (2014). The impact of distributive justice, procedural justice, and affective commitment on turnover intention among public and private sector employees in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 4(6), 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J., & Davies, F. (2005). Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: An analysis of public sector workers. Public Management Review, 7(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D. E., Sanders, K., Rodrigues, R., & Oliveira, T. (2021). Signalling theory as a framework for analysing human resource management processes and integrating human resource attribution theories: A conceptual analysis and empirical exploration. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(3), 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D. E., & Woodrow, C. (2012). Exploring the boundaries of human resource managers’ responsibilities. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(1), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines Iii, V. Y., Patient, D., & Guerrero, S. (2024). The fairness of human resource management practices: An assessment by the justice sensitive. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1355378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research (Volume 8, Issue 1, pp. 102–117). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, C. M., Holtz, B. C., Griepentrog, B. K., Brewer, L. M., & Marsh, S. M. (2016). Investigating the effects of applicant justice perceptions on job offer acceptance. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. (2013). Does fair treatment in the workplace matter? An assessment of organizational fairness and employee outcomes in government. The American Review of Public Administration, 43(5), 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D. A., Griffin, M. A., & Gavin, M. B. (2000). The application of hierarchical linear modeling to organizational research. In K. J. Klein, & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 467–511). Jossey-Bass/Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulin, C. L. (1987). A psychometric theory of evaluations of item and scale translations: Fidelity across languages. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18(2), 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulin, C. L., & Smith, P. C. (1965). A linear model of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49(3), 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S., & Shahzad, K. (2022). Unpacking perceived organizational justice-organizational cynicism relationship: Moderating role of psychological capital. Asia Pacific Management Review, 27(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J. (2018). The role of social support in the relationship between job demands and employee attitudes in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 31(6), 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. J., Noh, S. C., & Kim, I. (2018). Relative deprivation of temporary agency workers in the public sector: The role of public service motivation and the possibility of standard employment. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilroy, J., Dundon, T., & Townsend, K. (2023). Embedding reciprocity in human resource management: A social exchange theory of the role of frontline managers. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(2), 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Choi, D., Guay, R. P., & Chen, A. (2024). How does fairness promote innovative behavior in organizational change?: The importance of social context. Applied Psychology, 73(3), 1233–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P. S., & Moon, M. J. (2002). Current public sector reform in Korea: New public management in practice. Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 1(1), 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klandermans, B., Hesselink, J. K., & Van Vuuren, T. (2010). Employment status and job insecurity: On the subjective appraisal of an objective status. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31(4), 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçük, B. A. (2022). Understanding the employee job satisfaction depending on manager’s fair treatment: The role of cynicism towards the organization and co-worker support. European Review of Applied Psychology, 72(6), 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E. G., Keena, L. D., Leone, M., May, D., & Haynes, S. H. (2020). The effects of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction and organizational commitment ofcorrectional staff. The Social Science Journal, 57(4), 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, Y. Y., Binti Azizan, N. A., & Sorooshian, S. (2015). How are the performance of small businesses influenced by HRM practices and governmental support? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, B. H., & Kwon, H. (2007). Non-regular work in Korea. In Globalisation and work in Asia (pp. 249–274). Chandos Publishing. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). Springer. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ling, B., Yao, Q., Liu, Y., & Chen, D. (2024). Fairness matters for change: A multilevel study on organizational change fairness, proactive motivation, and change-oriented OCB. PLoS ONE, 19(10), e0312886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B. J., & Scott, B. A. (2012). Integrating social exchange and affective explanations for the receipt of help and harm: A social network approach. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology, 1(3), 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marien, S., & Werner, H. (2019). Fair treatment, fair play? The relationship between fair treatment perceptions, political trust and compliant and cooperative attitudes cross-nationally. European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, A., & Fletcher, C. (2004). Employee development: An organizational justice perspective. Personnel Review, 33(1), 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, E. (2018). Impact of job satisfaction on public service quality: Evidence from Syria. Serbian Journal of Management, 13(2), 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Employment Labor. (2022). Public sector non-regular employment improvement system. Available online: http://public.moel.go.kr/pub_home/intro.do?curr_menu_id=66 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ministry of Employment Labor. (2023). The survey on labor conditions by employment type. Available online: http://laborstat.moel.go.kr/hmp/tblInfo/TblInfoList.do?menuId=0010001100101104&leftMenuId=0010001100101&bbsId (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(6), 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, R. H., Niehoff, B. P., & Organ, D. W. (1993). Treating employees fairly and organizational citizenship behavior: Sorting the effects of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and procedural justice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6(3), 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M., & Kang, J. (2017). Job satisfaction of non-standard workers in Korea: Focusing on non-standard workers’ internal and external heterogeneity. Work, Employment and Society, 31(4), 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, G. S. (2013). Impact of organizational justice on satisfaction, commitment and turnover intention: Can fair treatment by organizations make a difference in their workers’ attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Human Sciences, 10(2), 260–284. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, V. (2009). Trust incident account model: Preliminary indicators for trust rhetoric and trust or distrust in blogs. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1), 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, J., Alam, M. M., Mohamed, D. I. B., & Rafidi, M. (2017). Does job satisfaction, fair treatment, and cooperativeness influence the whistleblowing practice in Malaysian Government linked companies? Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 9(3), 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2007). Union density and determinants of union membership in 18 EU countries: Evidence from micro data, 2002/03. Industrial Relations Journal, 38(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J. Y., Nam, E. Y., & Hong, D. S. (2016). Work-related attitudes of non-regular and regular workers in Korea: Exploring distributive justice as a mediator. Development and Society, 45(1), 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (2003). HRMR special issue: Fairness and human resources management. Human Resource Management Review, 13(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudin, S. (2011). Fairness of and satisfaction with performance appraisal process. Journal of Global Management, 2(1), 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Y. K., & Hu, H. H. S. (2021). The impact of airline internal branding on work outcomes using job satisfaction as a mediator. Journal of Air Transport Management, 94, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R., & Bies, R. J. (1990). Beyond formal procedures: The interpersonal context of procedural justice. In J. S. Carroll (Ed.), Applied social psychology and organizational settings (1st ed., pp. 77–98). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Waeyenberg, T., Peccei, R., & Decramer, A. (2022). Performance management and teacher performance: The role of affective organizational commitment and exhaustion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(4), 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, R., & Steensma, H. (2003). Physiological relaxation: Stress reduction through fair treatment. Social Justice Research, 16(2), 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veseli, A., & Çetin, F. (2024). The impact of HRM practices on OCB-I and OCB-O, with mediating roles of organizational justice perceptions: Moderating roles of gender. Journal of Economics & Management, 46(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., & Maxwell, S. E. (2015). On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wears, K. H., & Fisher, S. L. (2012). Who is an employer in the triangular employment relationship? Sorting through the definitional confusion. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 24(3), 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 209–231). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., Payne, S. C., Horner, M. T., & Alexander, A. L. (2016). Individual difference predictors of perceived organizational change fairness. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T. W. (2021). The effects of organizational justice, trust and supervisor–subordinate guanxi on organizational citizenship behavior: A social-exchange perspective. Management Research Review, 45(8), 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2(df) | RMSEA | SRMR Within | SRMR Between | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: 4 factors | 206.55 (36) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Model 2: 2 factors | 469.03 (37) | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.69 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Level | ||||||||

| 1. Age | 42.1 | 10.44 | ||||||

| 2. Sex | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.07 * | |||||

| 3. Education level | 2.83 | 0.6 | −0.36 ** | −0.09 ** | ||||

| 4. Union member | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | |||

| 5. Job tenure | 7.09 | 4.35 | 0.27 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| 6. Perceived fair treatment | 3.56 | 0.82 | 0.11 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.07 * | |

| 7. Job satisfaction | 3.42 | 0.77 | 0.11 ** | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.05 * | 0.64 ** |

| Organizational Level | ||||||||

| 1. Number of employees | 1254.52 | 2645.85 | ||||||

| 2. Existence of union | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.25 ** | |||||

| 3. Public organization type | 1.15 | 0.36 | −0.09 | −0.04 | ||||

| 4. HR practices | 1.22 | 1.11 | 0.17 | 0.19 * | 0.05 | |||

| 5. Perceived government support | 3.58 | 0.81 | 0.17 | −0.42 * | −0.15 | −0.17 |

| Job Satisfaction | Perceived Fair Treatment | Job Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intercept | 0.01 | 0.11 * | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Level 1—Employee | ||||

| Age | 0.01 * | 0.01 | 0.01 * | 0.00 * |

| Sex | 0.00 | −0.15 * | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Education | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Union member | −0.11 * | 0 | −0.11 * | −0.12 * |

| Job tenure | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Perceived fair treatment | 0.60 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.60 ** | |

| Job satisfaction | - | |||

| Level 2—Manager | ||||

| Number of employees | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Existence of union | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Public organization type | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| HR practices | - | 0.06 * | - | - |

| Perceived Government support | - | - | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Cross-level moderation | ||||

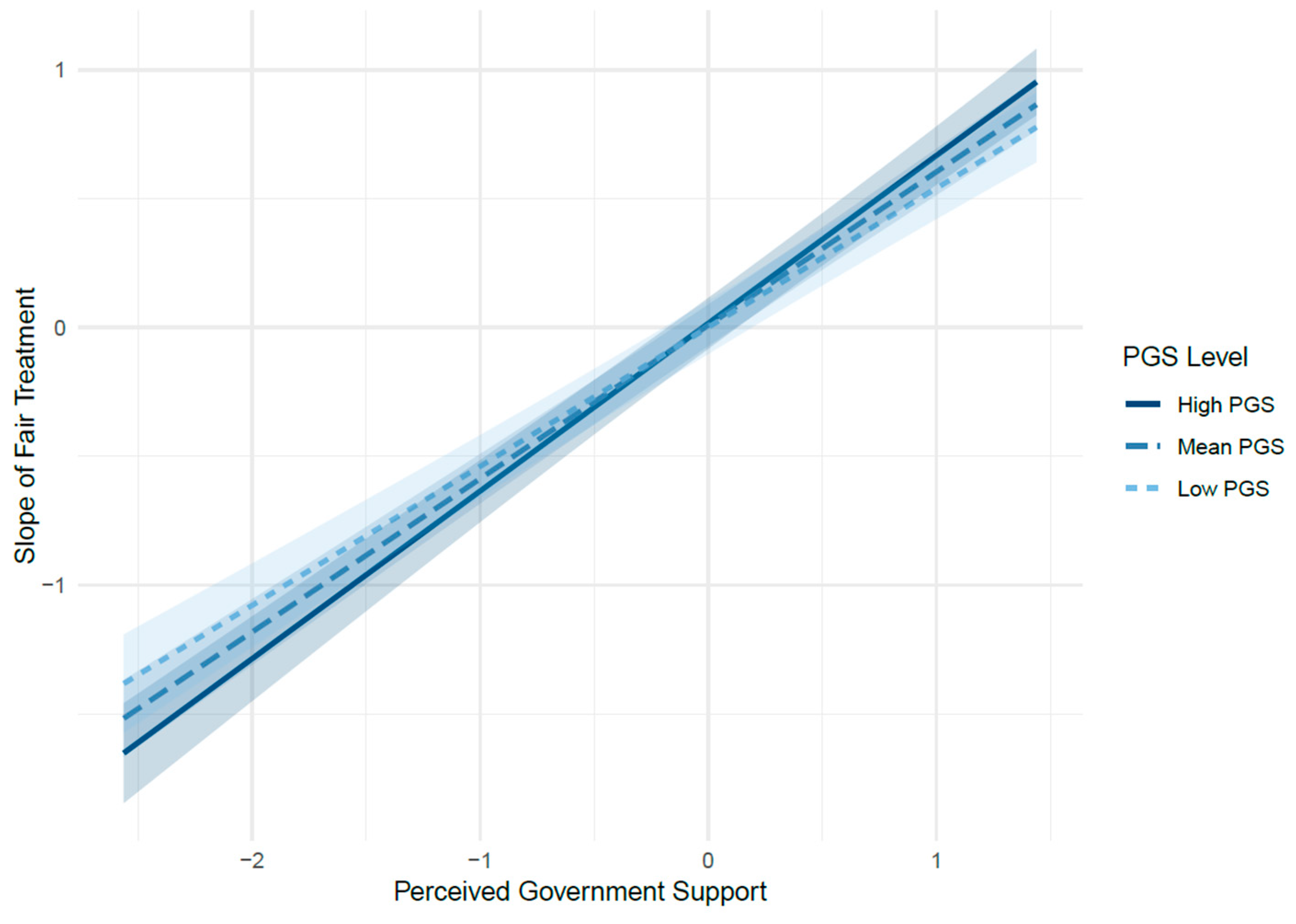

| Perceived fair treatment × Perceived government support | - | - | - | 0.06 * |

| Marginal R2 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Conditional R2 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | my job | colleagues | supervisor | promotion | income |

| Intercept | 2.63 ** | 3.02 ** | 3.57 ** | 3.65 ** | 3.07 ** |

| Perceived Fair treatment | 0.54 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.68 ** |

| (Std. Error) | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| (t-value) | −16.59 | −17.75 | −16.8 | −17.21 | −17.63 |

| Dependent Variable: Job Satisfaction | Model 1 (Individual-Level Union) | Model 2 (Organizational-Level Union) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Perceived fair treatment | 0.59 ** | 0.59 ** |

| Individual-Level Union Membership | −0.12 ** | - |

| Organizational-Level Existence of union | - | 0.09 |

| Interaction Term | ||

| Perceived fair treatment × Individual-Level Union Membership | −0.11 * | - |

| Perceived fair treatment × Organizational-Level Existence of union | - | −0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, H.; Cho, K.; Jung, H. Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Analysis of Employment Transition. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111524

Cho H, Cho K, Jung H. Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Analysis of Employment Transition. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111524

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Hyunmin, Kyujun Cho, and Heungjun Jung. 2025. "Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Analysis of Employment Transition" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111524

APA StyleCho, H., Cho, K., & Jung, H. (2025). Fair Treatment and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Analysis of Employment Transition. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111524