Implementation Fidelity in Early Intervention for Eating Disorders—A Multisite Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

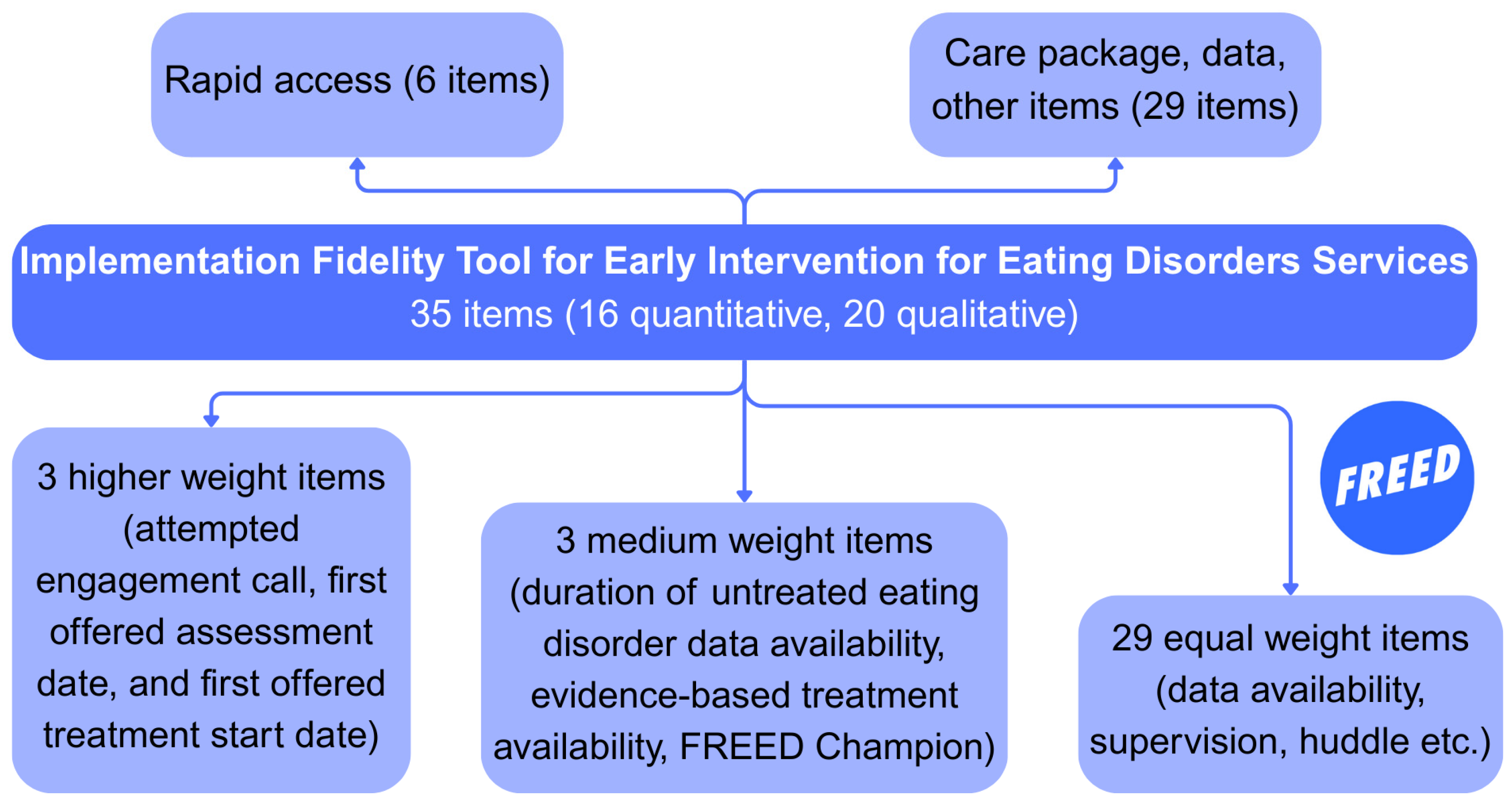

2.2. Fidelity Tool

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Approval

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility

“I really like the fidelity tool and how it has been developed and piloted. Having received our report, I can see how it is going to influence improvement in our FREED service, even within resource limitations, by helping us know where to focus that resource and increase motivation as well.”

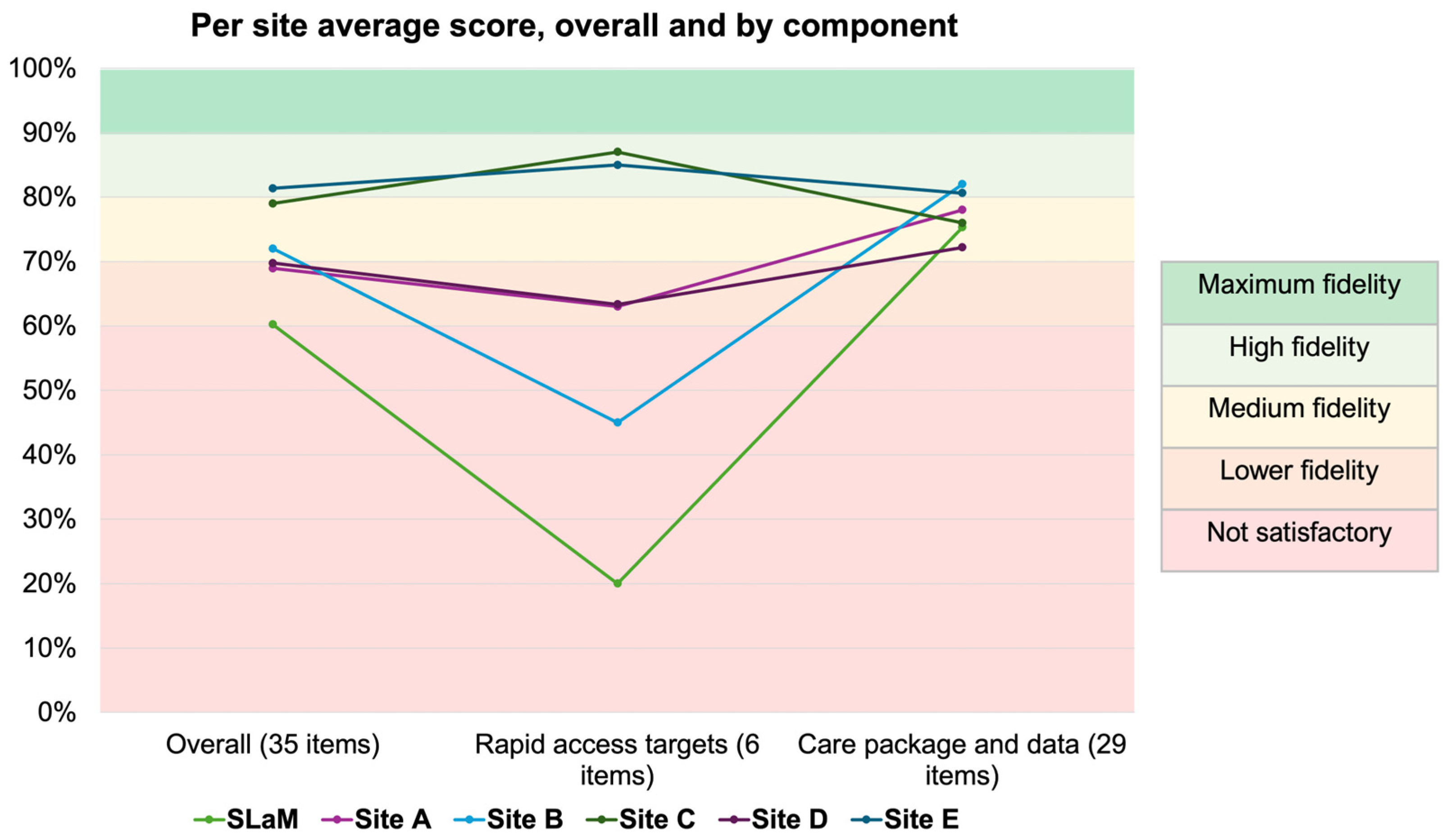

3.2. Fidelity Scores

3.3. IRR

4. Discussion

4.1. Fidelity Scores—The Importance of Context

4.2. Other Patterns of Fidelity

4.3. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NHS | National Health Service |

| FREED | First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders |

| ED | Eating Disorder |

| DUED | Duration of Untreated Eating Disorder |

| RE-AIM | Reach, Effectiveness/Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance |

| KCL | King’s College London |

| IRR | Inter-rater Reliability |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| COVID | Coronavirus Disease |

| ARFID | Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder |

| EDCRN | Eating Disorders Clinical Research Network |

| SLaM | South London and Maudsley |

Appendix A. Inter-Rater Reliability for All Sites

| Site | Kappa Quadratic | Kappa Linear | ICC3k |

| SLaM | 0.991 | 0.980 | 0.998 |

| A | 0.983 | 0.949 | 0.992 |

| B | 0.941 | 0.871 | 0.970 |

| C | 0.933 | 0.859 | 0.966 |

| D | 0.934 | 0.880 | 0.968 |

| E | 0.967 | 0.915 | 0.984 |

| 1 | Missing data are partly due to a lag in data collection (e.g., referrals may not yet have an agreed diagnosis whilst waiting for assessment); patient data are updated over time as patients progress through assessment and treatment. |

References

- Aarons, G. A., Sommerfeld, D. H., Hecht, D. B., Silovsky, J. F., & Chaffin, M. J. (2009). The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addington, D. (2021). The first episode psychosis services fidelity scale 1.0: Review and update. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, 2(1), sgab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addington, D., Noel, V., Landers, M., & Bond, G. R. (2020). Reliability and feasibility of the first-episode psychosis services fidelity scale-revised for remote assessment. Psychiatric Services, 71(12), 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. L., Courtney, L., Croft, P., Hyam, L., Mills, R., Richards, K., Ahmed, M., & Schmidt, U. (2025). Programme-led and focused interventions for recent onset binge/purge eating disorders: Use and outcomes in the first episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders (FREED) network. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 58(2), 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. L., Mountford, V., Brown, A., Richards, K., Grant, N., Austin, A., Glennon, D., & Schmidt, U. (2020). First episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders (FREED): From research to routine clinical practice. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(5), 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. L., Mountford, V. A., Elwyn, R., Flynn, M., Fursland, A., Obeid, N., Partida, G., Richards, K., Schmidt, U., Serpell, L., Silverstein, S., & Wade, T. (2023). A framework for conceptualising early intervention for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 31(2), 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, T., & Bryant-Waugh, R. (2023). Current evidence for avoidant restrictive food intake disorder: Implications for clinical practice and future directions. JCPP Advances, 3(2), e12160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A., Flynn, M., Richards, K., Hodsoll, J., Duarte, T. A., Robinson, P., Kelly, J., & Schmidt, U. (2021). Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(3), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayton, A., & Ibrahim, A. (2018). Does UK medical education provide doctors with sufficient skills and knowledge to manage patients with eating disorders safely? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 94(1113), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D. R., Swanson, S. J., Reese, S. L., Bond, G. R., & McLeman, B. M. (2015). Supported employment fidelity review manual. A companion guide to the evidence-based IPS supported employment fidelity scale (3rd ed.). Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center. Available online: https://ipsworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ips-fidelity-manual-3rd-edition_2-4-16.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bond, G. R., & Drake, R. E. (2020). Assessing the fidelity of evidence-based practices: History and current status of a standardized measurement methodology. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(6), 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, G. R., Williams, J., Evans, L., Salyers, M., Kim, H.-W., Sharpe, H., & Leff, H. (2000). Psychiatric rehabilitation fidelity toolkit. Human Services Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., & Resnick, B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A., McClelland, J., Boysen, E., Mountford, V., Glennon, D., & Schmidt, U. (2018). The FREED project (first episode and rapid early intervention in eating disorders): Service model, feasibility and acceptability. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(2), 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, C., Wilkins, J., İnce, B., Hemmings, A., Kuehne, C., Douglas, D., Phillips, M., Sharpe, H., & Schmidt, U. (2025). Food insecurity in individuals with eating disorders: A UK-wide survey of impact, help seeking, and suggestions for guidance [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King’s College London. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, J., Kimber, M., Barwick, M., McVey, G., Findlay, S., Webb, C., Niccols, A., & Lock, J. (2021). Assessing fidelity to family-based treatment: An exploratory examination of expert, therapist, parent, and peer ratings. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromarty, P. (2024). The concept of service model fidelity in talking therapies. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 17, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csillag, C., Nordentoft, M., Mizuno, M., McDaid, D., Arango, C., Smith, J., Lora, A., Verma, S., Di Fiandra, T., & Jones, P. B. (2018). Early intervention in psychosis: From clinical intervention to health system implementation. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(4), 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EY, The University of Sydney & The George Institute. (2020). Evaluation of the early psychosis youth services program-final report. Federal Department of Health Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, M., Pawliuk, N., Pope, M., MacDonald, K., Boruff, J., Shah, J., Malla, A., & Iyer, S. N. (2023). A scoping review of measures used in early intervention services for psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 74(5), 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, A., Austin, A., McClelland, J., Brown, A., Glennon, D., Mountford, V., Grant, N., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2020). First episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders: A two-year follow-up. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(1), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L., Hyam, L., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2025). The continuing impact of COVID-19 on eating disorder early intervention services in England: An investigation of referral numbers and presentation characteristics. European Psychiatry, 68(1), e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Innovation Network. (2024). National programme: Early intervention eating disorders. Available online: https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/projects/national-programme-early-intervention-eating-disorders/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Hyam, L., Gallagher, L. M., Di Clemente, G., Killackey, E., Glennon, D., Griffiths, J., Mills, R., Wilkins, J., Ahmed, M., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2025). To fidelity and beyond: Development of an implementation fidelity tool for early intervention for eating disorders services [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King’s College London. [Google Scholar]

- Hyam, L., Richards, K. L., Allen, K. L., & Schmidt, U. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on referral numbers, diagnostic mix, and symptom severity in eating disorder early intervention services in England. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(1), 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, T., Smith, I., Downs, J., Carnegie, A., Kakar, S., Meldrum, L., Qi, L., Foye, U., Malouf, C., Baker, S., Virgo, H., Okoro, M., Griffiths, J., Munblit, D., Herle, M., Schmidt, U., Byford, S., Landau, S., Llewellyn, C., … Nicholls, D. (2025). Agreeing a set of biopsychosocial variables for collection across the UK Eating Disorders Clinical Research Network: A consensus study using adapted nominal group technique. BMJ Mental Health, 28(1), e301760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkaid, M., Fuhrer, R., McGowan, S., & Malla, A. (2025). Preliminary evaluation of a questionnaire for assessing fidelity of early intervention for psychosis services. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 60(1), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebow, J., Narr, C., Mattke, A., Gewirtz O’Brien, J. R., Billings, M., Hathaway, J., Vickers, K., Jacobson, R., & Sim, L. (2021). Engaging primary care providers in managing pediatric eating disorders: A mixed methods study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M., Gao, Q., & Yu, T. (2023). Kappa statistic considerations in evaluating inter-rater reliability between two raters: Which, when and context matters. BMC Cancer, 23(1), 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, C. (2003). Fidelity criteria: Development, measurement, and validation. The American Journal of Evaluation, 24(3), 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueser, K. T., Meyer-Kalos, P. S., Glynn, S. M., Lynde, D. W., Robinson, D. G., Gingerich, S., Penn, D. L., Cather, C., Gottlieb, J. D., Marcy, P., Wiseman, J. L., Potretzke, S., Brunette, M. F., Schooler, N. R., Addington, J., Rosenheck, R. A., Estroff, S. E., & Kane, J. M. (2019). Implementation and fidelity assessment of the NAVIGATE treatment program for first episode psychosis in a multi-site study. Schizophrenia Research, 204, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyser, D., Sysko, R., Webb, L., & Hildebrandt, T. (2021). Treatment fidelity in eating disorders and psychological research: Current status and future directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(12), 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Richards, K. L., Flynn, M., Austin, A., Lang, K., Allen, K. L., Bassi, R., Brady, G., Brown, A., Connan, F., Franklin-Smith, M., Glennon, D., Grant, N., Jones, W. R., Kali, K., Koskina, A., Mahony, K., Mountford, V. A., Nunes, N., Schelhase, M., … Schmidt, U. (2021). Assessing implementation fidelity in the First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders service model. BJPsych Open, 7(3), e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. L., Hyam, L., Allen, K. L., Glennon, D., Di Clemente, G., Semple, A., Jackson, A., Belli, S. R., Dodge, E., Kilonzo, C., Holland, L., & Schmidt, U. (2023). National roll-out of early intervention for eating disorders: Process and clinical outcomes from first episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 17(2), 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, U., Brown, A., McClelland, J., Glennon, D., & Mountford, V. A. (2016). Will a comprehensive, person-centered, team-based early intervention approach to first episode illness improve outcomes in eating disorders? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(4), 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippy, R., Efstathopoulou, L., Simes, E., Davis, M., Howell, S., Morris, B., Owrid, O., Stoll, N., Fonagy, P., & Moore, A. (2025). Effect of a needs-based model of care on the characteristics of healthcare services in England: The i-THRIVE national implementation programme. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 34, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, D., King, E., Harris, S., Hollyman, J., Costello, K., Galvin, E., Stock, M., Schmidt, U., Downs, J., Sekar, M., Newell, C., Clark-Stone, S., Wicksteed, A., Foster, C., Battisti, F., Williams, L., Jones, R., Beglin, S., Anderson, S., … Ayton, A. (2024). The alarms should no longer be ignored: Survey of the demand, capacity and provision of adult community eating disorder services in England and Scotland before COVID-19. BJPsych Bulletin, 48(4), 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, T. D. (2025). Program-led and focused psychological interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 58(5), 813–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G., & Turner, H. (2016). Therapist drift redux: Why well-meaning clinicians fail to deliver evidence-based therapy, and how to get back on track. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J., Ahmed, M., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2025). Intersectionality in help-seeking for eating disorders: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G., Farrelly, S., Thompson, A., Stavely, H., Albiston, D., van der El, K., McGorry, P., & Killackey, E. (2021). The utility of a fidelity measure to monitor implementation of new early psychosis services across Australia. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 15(5), 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall Score Label | % Score | Weighted Summed Score |

|---|---|---|

| Not satisfactory | <60% | <299 |

| Lower fidelity | 60–69% | 300–344 |

| Medium fidelity | 70–79% | 345–394 |

| High fidelity | 80–89% | 395–444 |

| Maximum fidelity | >90% | 445–500 |

| Service 1 | Service Description | Referrals (n) | Overall Fidelity Score (%) | Component 1: Rapid Access Targets (%) | Component 2: Care Package and Data (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole network | - | 242 | 72 | 57 | 77 |

| SLaM | Adult service Urban | 36 | 60 | 20 | 75 |

| A | Adult service Urban/rural | 52 | 69 | 63 | 78 |

| B | All-age Urban/rural | 68 | 72 | 45 | 82 |

| C | Adult service Urban/rural | 17 | 79 | 87 | 76 |

| D | Adult service Urban/rural | 31 | 70 | 63 | 72 |

| E | Adult service Urban/rural | 38 | 81 | 85 | 81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyam, L.; Gallagher, L.; Tsivos, Z.; Macnab, S.; Kirton, B.; Palmer, E.; Killackey, E.; Allen, K.L.; Schmidt, U. Implementation Fidelity in Early Intervention for Eating Disorders—A Multisite Pilot Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111521

Hyam L, Gallagher L, Tsivos Z, Macnab S, Kirton B, Palmer E, Killackey E, Allen KL, Schmidt U. Implementation Fidelity in Early Intervention for Eating Disorders—A Multisite Pilot Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111521

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyam, Lucy, Lucy Gallagher, Zoe Tsivos, Sarah Macnab, Ben Kirton, Emily Palmer, Eóin Killackey, Karina L. Allen, and Ulrike Schmidt. 2025. "Implementation Fidelity in Early Intervention for Eating Disorders—A Multisite Pilot Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111521

APA StyleHyam, L., Gallagher, L., Tsivos, Z., Macnab, S., Kirton, B., Palmer, E., Killackey, E., Allen, K. L., & Schmidt, U. (2025). Implementation Fidelity in Early Intervention for Eating Disorders—A Multisite Pilot Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111521