The Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution Among College Students: Serial Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

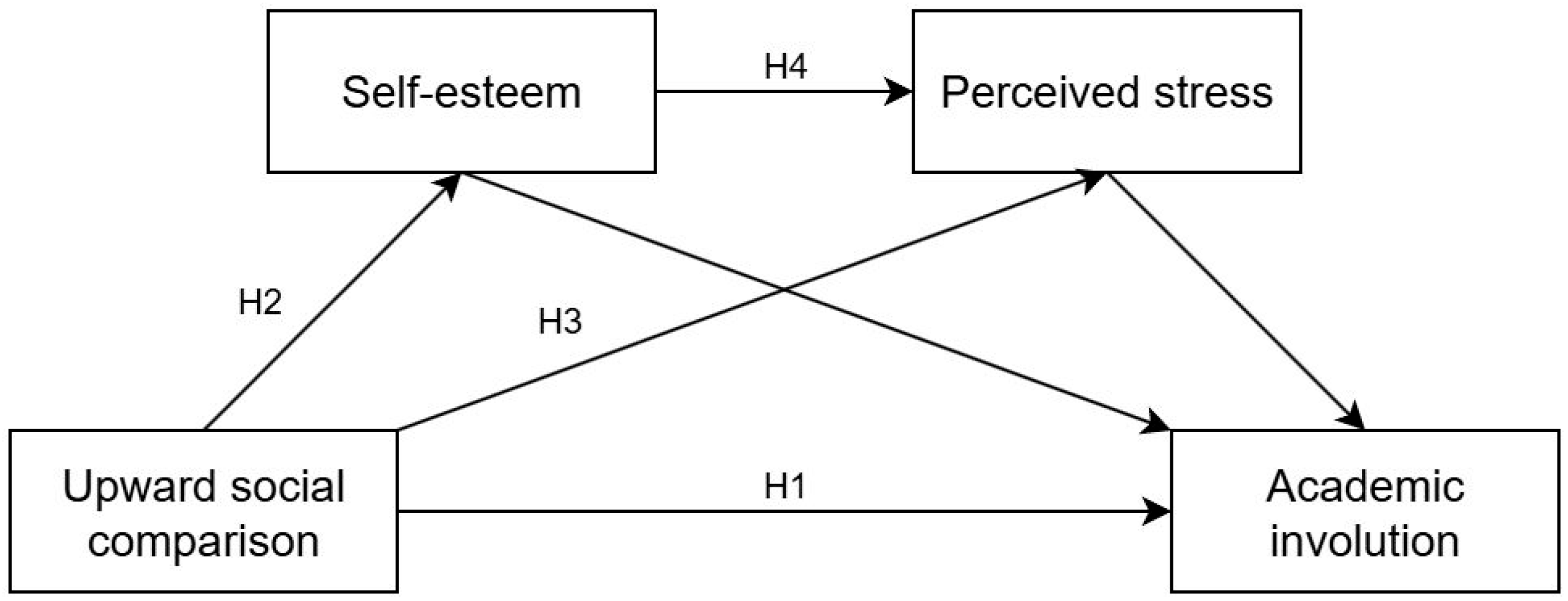

1.1. Upward Social Comparison and Academic Involution

1.2. Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem

1.3. Mediating Effect of Perceived Stress

1.4. Serial Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Upward Social Comparison Scale

2.2.2. Self-Esteem Scale

2.2.3. Chinese Perceived Stress Scale

2.2.4. College Students’ Academic Involution Scale

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

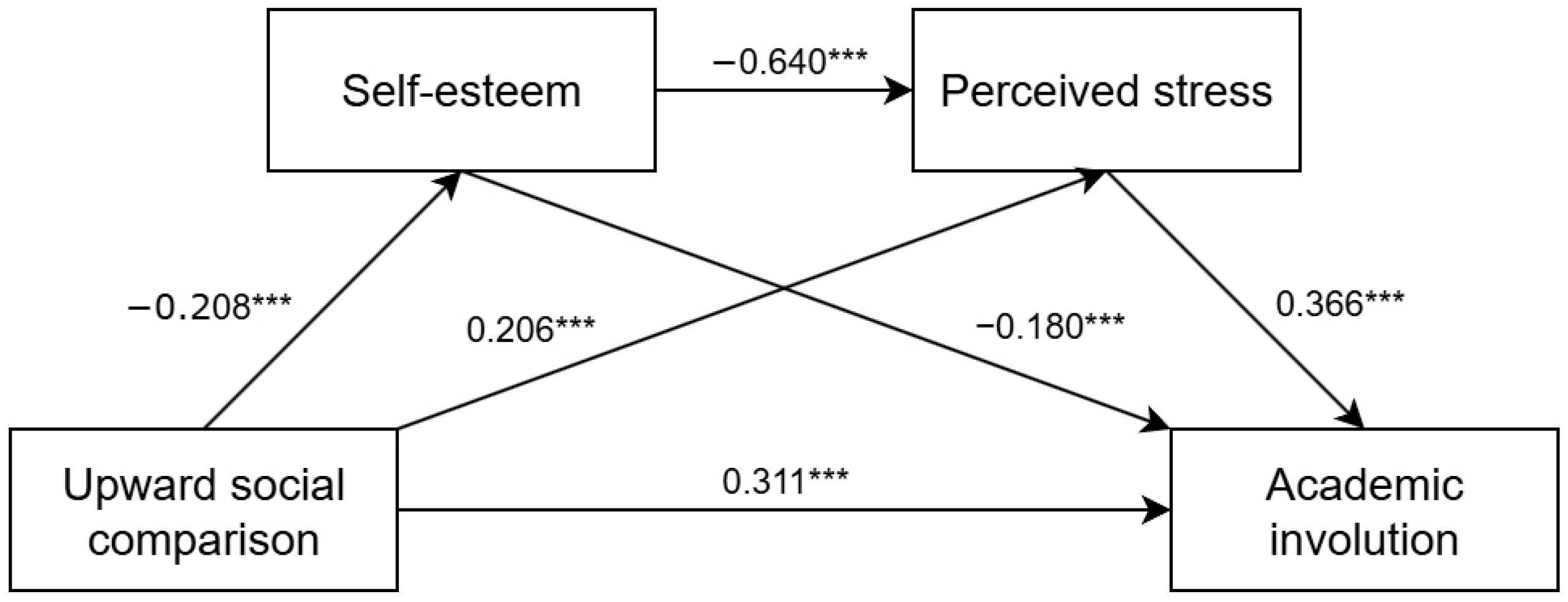

3.3. Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution

4.2. Role of Self-Esteem as a Mediator

4.3. Role of Perceived Stress as a Mediator

4.4. Serial Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress

4.5. Research Implications

4.6. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| USC | Upward social comparison |

| SE | Self-esteem |

| PS | Perceived stress |

| AI | Academic involution |

References

- Alfasi, Y. (2019). The grass is always greener on my Friends’ profiles: The effect of Facebook social comparison on state self-esteem and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, R., Quiamzade, A., & Meier, L. L. (2024). Depressive symptoms and upward social comparisons during Instagram use: A vicious circle. Personality and Individual Differences, 217, 112458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Liu, X., & Liu, Z. (2013). The mediating effects of social comparison on the relationship between achievement goal and academic self-efficacy: Evidence from the junior high school students. Journal of Psychological Science, 36(6), 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainter, T. E. G., & Ackerman, M. L. (2022). Conformity behaviors: A qualitative phenomenological exploration of binge drinking among female college students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, F., Koenig, J., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2024). Indicated stress prevention addressing adolescents with high stress levels based on principles of acceptance and commitment therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 93(3), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. G., Davenport, S. C., & Mazanov, J. (2007). Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). Journal of Adolescence, 30(3), 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K., Khazanchi, S., & Nazarian, D. (2010). The relationship between stressors and creativity: A meta-analysis examining competing theoretical models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, Y., & Zhen, X. (2004). A review of the research work of cognitive processing bias of self-esteem level. Psychology Science, (05), 1184–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Zhao, X., Zeng, M., Li, J., Ren, X., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., & Yang, J. (2021). Collective self-esteem and perceived stress among the non-infected general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic: A multiple mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J., Zeng, X., Li, G., Xu, L., Shi, G., & Peng, S. (2024). Effect of upward social comparison on college students’ academic involution: The mediating effects of anxiety and the moderating effects of self-affirmation. China Journal of Health Psychology, 32(06), 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Zhang, Z., & Xu, L. (2023). The compilation of the college students’ academic involution scale. Journal of Jianghan University (Social Sciences), 40(5), 117–124+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. (2021). Awakening and breakthrough: A semantic analysis of internet buzzwords “Workers” and “Involution”. New Media Research, 7(11), 6–13+34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-J., Chang, E.-C., Dai, Q., & Wong, V. (2013). Replacement between conformity and counter-conformity in consumption decisions. Psychological Reports, 112(1), 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. L. (2000). Among the better ones: Upward assimilation in social comparison. In J. Suls, & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of social comparison (pp. 159–171). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, G., Li, G., Yuan, Y., Liu, B., & Yang, L. (2022). Structural dimension exploration and measurement scale development of employee involution in China’s workplace field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjaian, B., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Vonk, J. (2017). The relationship between approval-based contingent self-esteem and conformity is influenced by sex and task difficulty. Personality and Individual Differences, 115, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Fried, E., De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2019). Negative influences of Facebook use through the lens of network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, N. H., Choukas-Bradley, S., Giletta, M., Telzer, E. H., Cohen, G. L., & Prinstein, M. J. (2024). Why adolescents conform to high-status peers: Associations among conformity, identity alignment, and self-esteem. Child Development, 95(3), 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Guo, Z., Yan, Y., Wang, J., Zhan, X., Li, X., Tian, Y., & Wang, P. (2023). Relationship between shyness and cyberbullying in different study stages: The mediating effects of upward social comparison and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 42(26), 22290–22300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S. M., Tor, A., & Schiff, T. M. (2013). The psychology of competition: A social comparison perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J. P., Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2018). A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychological Bulletin, 144(2), 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valero, G., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., & Puertas-Molero, P. (2019). Use of meditation and cognitive behavioral therapies for the treatment of stress, depression and anxiety in students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D., Shen, X., & Liu, Q.-Q. (2020). The relationship between upward social comparison on SNSs and excessive smartphone use: A moderated mediation analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C., Tai, K.-H., Hwang, M.-Y., & Lin, C.-Y. (2022). Social comparison effects on students’ cognitive anxiety, self-confidence, and performance in Chinese composition writing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1060421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.-T., Liu, Q.-Q., & Ma, Z.-F. (2023). Does upward social comparison on SNS inspire adolescent materialism? focusing on the role of self-esteem and mindfulness. The Journal of Psychology, 157(1), 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T., Chen, Y., & Zhang, K. (2024). Effects of social media use on employment anxiety among Chinese youth: The roles of upward social comparison, online social support and self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1398801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juth, V., Smyth, J. M., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2008). How do you feel? Self-esteem predicts affect, stress, social interaction, and symptom severity during daily life in patients with chronic illness. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(7), 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupcewicz, E., Cybulska, A. M., Schneider-Matyka, D., Jastrzębski, P., Bentkowska, A., & Grochans, E. (2024). Global self-esteem and coping with stress by Polish students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1419771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A., Shi, Y., Zhao, Y., & Ni, J. (2024). Influence of academic involution atmosphere on college students’ stress response: The chain mediating effect of relative deprivation and academic involution. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Kvintova, J., & Vachova, L. (2025). Parents’ social comparisons and adolescent self-esteem: The mediating effect of upward social comparison and the moderating influence of optimism. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1473318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Tu, Y., Yang, H., Gao, J., Xu, Y., & Yang, Q. (2022). Have you “involution” today—Competition psychology scale for college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 951931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.-Y., Li, Y., Guo, L., & Yang, G.-E. (2024). Achievement motivation and mental health among medical postgraduates: The chain mediating effect of self-esteem and perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1483090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, C. A., Vanman, E. J., & Tobin, S. J. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effects of social media exposure to upward comparison targets on self-evaluations and emotions. Media Psychology, 26(5), 612–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijen, C., Turner, M., Jones, M. V., Sheffield, D., & McCarthy, P. (2020). A theory of challenge and threat states in athletes: A revised conceptualization. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X., Jiang, Y., & Lian, R. (2024). The effect of social media upward comparison on Chinese adolescent learning engagement: A moderated multiple mediation model. BMC Psychology, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritvo, P., Ahmad, F., El Morr, C., Pirbaglou, M., Moineddin, R., & MVC Team. (2021). A mindfulness-based intervention for student depression, anxiety, and stress: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 8(1), e23491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlechter, P., Meyer, T., Hagen, M., Baranova, K., & Morina, N. (2025). Comparative thinking among university students: An ecological momentary assessment of upward comparisons, stress and learning behavior during exam preparation. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, D. A., & Koomen, W. (2005). Competition, cooperation, and the effects of others on me. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R. H., Perry, R. P., Renaud, R. D., & Hladkyj, S. (2013). Looking beyond grades: Comparing self-esteem and perceived academic control as predictors of first-year college students’ well-being. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J., Martin, R., & Wheeler, L. (2002). Social comparison: Why, with whom, and with what effect? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(5), 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Hu, W., Zhao, X., Liu, Y., Ren, Y., Tang, Z., & Yang, J. (2024). The role of personal, relational, and collective self-esteem in predicting acute salivary cortisol response and perceived stress. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 16(3), 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J., Li, B., & Zhang, R. (2025). The impact of upward social comparison on social media on appearance anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Yang, Y., & Cui, T. (2024). Development and validation of an Academic Involution Scale for College Students in China. Psychology in the Schools, 61(3), 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Li, J., Zhao, X., Zhou, M., Zhang, Y., Yu, L., Yang, Z., & Yang, J. (2023). Perceived stress mediates the association between perceived control and emotional distress: The moderating role of psychological resources and sex differences. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 168, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Wang, X., & Ma, H. (1999). Manual of the mental health assessment scale. China Mental Health Journal Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtyna, E., Hyla, M., & Hachuła, A. (2024). Pain of threatened self: Explicit and implicit self-esteem, cortisol responses to a social threat and pain perception. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(9), 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, L. J., Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J. J. C. S., & Williams, S. E. (2023). Examining the associations between physical activity, self-esteem, perceived stress, and internalizing symptoms among older adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 95(6), 1274–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., & Shakibaei, G. (2025). The role of social comparison in online learning motivation through the lens of social comparison theory. Acta Psychologica, 258, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L., & Li, L. (2024). Upward social comparison and social anxiety among Chinese college students: A chain-mediation model of relative deprivation and rumination. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1430539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D., Zhang, H., Guo, S., & Zeng, W. (2022). Influence of anxiety on university students’ academic involution behavior during COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating effect of cognitive closure needs. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1005708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Li, M., & Han, Y. (2023). Whether and how will using social media induce social anxiety? The correlational and causal evidence from Chinese society. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1217415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T., & Huang, H. (2003). An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 24(9), 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, D., Wu, J., Zhang, M., Zeng, Q., Wang, J., Liang, J., & Cai, Y. (2022). Does involution cause anxiety? An empirical study from Chinese universities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Gong, Z., Shen, Y., & Wei, J. (2024). A motivational perspective on the educational arms race in China: Self-determination in out-of-school educational training among Chinese students and their parents. Current Psychology, 43(10), 9116–9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Zheng, J., Xu, Z., & Zhang, T. (2022). The transformation of parents’ perception of education involution under the background of “double reduction” policy: The mediating role of education anxiety and perception of education equity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 800039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Wang, M., Ding, L., Liu, J., Yuan, Y., Zhang, J., Feng, S., & Liu, Y. (2025). The effect of self-esteem on mobile phone addiction among college students: Sequential mediating effects of online upward social comparison and social anxiety. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 18, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Sulong, R. M., & Hassan, N. C. (2025). The impact of parents’ perceptions of the double reduction policy on educational anxiety: Parental involvement as a mediator and gender as a moderator. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2444803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Pan, C., Yao, S., Zhu, J., Ling, D., Yang, H., Xu, J., & Mu, Y. (2024). ‘Neijuan’ in China: The psychological concept and its characteristic dimensions. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 56(1), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Xia, J., Wang, X., & Cai, Y. (2025). Development and validation of Academic Publishing Involution Scale for College Teachers in China. Current Psychology, 44(1), 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Yan, W., Tao, L., & Zhang, J. (2024). The association between relative deprivation, depression, and youth suicide: Evidence from a psychological autopsy study. Omega, 89(4), 1691–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X., Wei, J., & Chen, C. (2022). The association between freshmen’s academic involution and college adjustment: The moderating effect of academic involution atmosphere. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 43(5), 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Age | 20.370 | 1.939 | −0.086 * | 1 | |||||

| 3. Grade | 2.500 | 1.271 | −0.135 ** | 0.814 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. USC | 3.464 | 0.890 | −0.048 | 0.119 ** | 0.086 * | 1 | |||

| 5. SE | 3.588 | 0.660 | 0.050 | −0.013 | −0.027 | −0.207 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. PS | 2.908 | 0.577 | −0.038 | 0.020 | 0.060 | 0.335 ** | −0.684 ** | 1 | |

| 7. AI | 3.033 | 0.679 | −0.102 ** | 0.111 ** | 0.093 * | 0.481 ** | −0.497 ** | 0.594 ** | 1 |

| Variables | SE | PS | AI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Gender | 0.038 | 1.038 | 0.009 | 0.355 | −0.062 | −2.268 * |

| Age | 0.054 | 0.866 | −0.098 | −2.165 * | 0.098 | 2.090 * |

| Grade | −0.048 | −0.765 | 0.106 | 2.342 * | −0.049 | −1.031 |

| USC | −0.208 | −5.676 *** | 0.206 | 7.674 *** | 0.311 | 10.703 *** |

| SE | −0.640 | −24.046 *** | −0.180 | −4.841 *** | ||

| PS | 0.366 | 9.438 *** | ||||

| R | 0.213 | 0.715 | 0.695 | |||

| R2 | 0.046 | 0.511 | 0.469 | |||

| F | 8.640 *** | 150.989 *** | 106.435 *** | |||

| Path | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95% CI Lower Limit | Boot 95% CI Upper Limit | Relative Mediation Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USC→SE→AI | 0.037 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.062 | 7.84% |

| USC→PS→AI | 0.075 | 0.013 | 0.051 | 0.102 | 15.89% |

| USC→SE→PS→AI | 0.049 | 0.011 | 0.029 | 0.070 | 10.38% |

| Total indirect effect | 0.161 | 0.020 | 0.121 | 0.201 | 34.11% |

| Direct effect | 0.311 | 0.029 | 0.254 | 0.368 | 65.89% |

| Total effect | 0.472 | 0.033 | 0.408 | 0.536 | 100.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, R.; Jin, Q. The Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution Among College Students: Serial Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111515

Wen R, Jin Q. The Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution Among College Students: Serial Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111515

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Ru, and Qingying Jin. 2025. "The Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution Among College Students: Serial Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111515

APA StyleWen, R., & Jin, Q. (2025). The Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Academic Involution Among College Students: Serial Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Perceived Stress. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111515