1. Introduction

Emojis are small graphical symbols that serve as a visual language in online communication. They have been designed to enhance text communication in online environments, but, as human connection and communication progressively shifts from physical to digital spaces, emojis have gained prevalence because they express emotions and carry complex meanings in a simple way (

Erle et al., 2022). Since 1988, when the first emoji-like set was released (

Emojitimeline, n.d.), the evolution of emojis and their prevalence in online communication (and beyond) are undeniable. Approximately 4000 emojis have been approved by Unicode, the international standard for text encoding (

Emojipedia, 2025a). While data about emoji usage across all platforms is not available, more than 166 million emojis have been copied from Emojipedia, the encyclopedia of emojis, and GetEmoji.com across all platforms, with 20 emojis copied each second (

Emojitracker, n.d.). The prevalence is such that users have been asking platforms to include new emojis. In addition, platforms and software are publishing press releases about emoji inclusion in their updates, and artificial intelligence emoji generators are created to cover excessive demand (

Feng et al., 2020;

Nerdbot, 2025). Admittedly, as a paralanguage, emojis have been used in different ways by different generations, with Generation Z, people born from 1997 to 2012, excessively using emojis at work or to create secret codes and meanings with emojis (

Emojipedia, 2025b;

India Today, 2025;

Abbasi et al., 2025;

Zahra & Ahmed, 2025;

Zhukova & Brehm, 2024).

Emojis are now embraced by marketers and advertisers in brand-to-consumer communication because of their unparalleled use to enhance it by conveying emotions and making it more vivid by describing objects, concepts, and situations with a simple icon.

In consumer behavior research, it is shown that people relate to brands as if they were people, and, at the same time, they expect brands to also satisfy emotional needs (

K.-J. Chen & Lin, 2021;

Delgado-Ballester et al., 2020). In this sense, emojis are also used in marketing strategy as tools to make the brand appear more human-like, what is called “anthropomorphism” (

Agrawal et al., 2020).

Beyond emotional expression, other significant benefits are that emojis seem to assist in grabbing the attention of users in an era where the attention span is diminishing (

Mark, 2023;

Bai et al., 2019;

Li et al., 2024;

Stoianova et al., 2024) and seem to improve readability, the comprehension of messages, and decrease their ambiguity (

J. Chen, 2023;

Daniel & Camp, 2020;

Boutet et al., 2021) because they serve as visual cues that make communication richer and easier to process when they are semantically and emotionally congruent with the text (

Barach et al., 2021;

Beyersmann et al., 2023).

Despite their increasing integration into digital marketing strategy and the fact that they have been studied extensively in linguistics and psychology (

Setyawan & Musthafa, 2024;

Bai et al., 2019), research on emojis in marketing and advertising is scattered across studies, and multiple contexts, diverse methods and theoretical frameworks are observed.

This fragmentation limits our ability to fully understand how, why, and with what results emojis are used in brand communication and creates obstacles for researchers and marketers. Because of the methodological and theoretical diversity of the field, without a systematic approach, researchers are prevented from establishing and using standard methods to assess emoji effects. Moreover, a systematic review would mitigate the scattered findings in the field and would shed light on the potentially more productive theoretical lenses to be used. On the other hand, despite the large volume of studies, practitioners now cannot make informed decisions about the use of emojis in their marketing strategies unless they study all available studies. Furthermore, since lower emphasis has been given to advertising contexts, marketers do not have evidence on how emojis work in persuasive speech. To sum up, the field needs a systematic study that unites existing knowledge so that both academics and practitioners can have a solid base for their future work.

To date and to our knowledge, no systematic literature review has synthesized the findings for brand communication in marketing and advertising.

Following

Palmatier et al. (

2018), this is a domain-based systematic review that maps the landscape of emoji research in marketing. We conduct a bibliometric and systematic literature review to provide a consolidated understanding of the field, following the TCCM (Theory-Context-Characteristics-Methodology) framework with the PRISMA-SLR process to maximize clarity and transparency. This study’s main contribution lies in the mapping, organization, and categorization of the existing literature that helped us draw an overview of the current state of knowledge. The synthesis of key findings and the identification of critical research gaps in the theoretical development, methodological approaches, contextual coverage, and emoji characteristics examined are two other major contributions. Taking all of the above into account, we create a future research agenda that would advance the work of academics and practitioners.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review Protocol

This systematic literature review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (

Page et al., 2021) and adhered to the principles of the Theory-Context-Characteristics-Methodology (TCCM) framework (

Palmatier et al., 2018). The review protocol was registered on 30 May 2025 on the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (

Vardikou et al., 2025b) under registration number INPLASY202405850 and is publicly available. Upon registration of the protocol, we ensured that no other similar research was reported in INPLASY.

2.2. Search Strategy

We developed a search strategy to identify relevant studies examining the use of emojis broadly in digital marketing and with a specific interest in advertising or e-commerce settings. The search was conducted in Scopus in May 2025, covering publications from 2002 to 2025. The choice of Scopus was justified to ensure that we had access to a larger pool of data and because it is a major database of publications’ metadata (

Pranckutė, 2021;

Khan et al., 2024). While Google Scholar has a larger pool of publications,

Martín-Martín et al. (

2018) have found that it also has a significant number of articles that are not published in journals.

First, we conducted a search of article titles, abstracts, and keywords to uncover if there was any other systematic literature review on emojis in marketing that we were not aware of, and the search returned none. Then search terms were combined using Boolean operators to capture all of the relevant literature. The Boolean search string used for titles, abstracts, and keywords was the following:

emoji OR emoticon OR emojis OR emoticons AND

“advertising” OR “ads” OR “advertisements” OR “marketing” OR “digital marketing” OR “ecommerce” OR “e-commerce” OR “e commerce”.

A total of 246 documents were initially found. When we applied the first criterion, English language, the search returned 233 documents, and when we filtered for articles published only in journals, the search returned 140 articles. To further justify our choice to include only journal articles despite the growing nature of our topic, we turned to other systematic literature reviews in marketing and consumer behavior that excluded articles published in proceedings or books, because the peer-review process in journals is rigorous (

Alalwan et al., 2017;

Khan et al., 2024). For the 140 remaining articles, we then performed the screening process, which is described in the next section.

2.3. Screening

All references retrieved were uploaded to Mendeley, a citation management tool, to manage duplicates. The screening of the deduplicated articles was performed using Rayyan, a web-based systematic review management platform that facilitates collaborative screening processes (

Z. Yu et al., 2018;

Ouzzani et al., 2016). Rayyan was selected for its several key advantages, including the following: (1) blind reviewing functionality that prevents reviewer bias during the screening process, (2) real-time collaboration features, (3) conflict resolution tools that highlight disagreements between reviewers, (4) tracking of screening decisions and rationales, (5) tagging of articles, and (6) desktop and mobile app availability to enable reviewers to collaborate seamlessly any time.

The screening was conducted by two independent reviewers who evaluated all identified articles against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The eligibility criteria comprised specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the highest academic level of information. Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) The article is published in English; (2) the article is a peer-reviewed journal article; (3) the study is framed in a digital marketing context; and (4) the use of emojis is between the brand and consumer. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The focus of research was on user-generated content; (2) the study has a purely linguistic analysis without a marketing or consumer focus.

Initially, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. When the topic was not clear from the article’s title and abstract, a full-text screening followed. The two reviewers screened independently and, throughout this process, Rayyan’s blind review feature ensured that neither reviewer was influenced by the other’s decisions. When disagreements arose between the two primary reviewers, a third independent reviewer was consulted. All screening decisions, conflicts, and resolutions were systematically documented within the Rayyan platform to maintain transparency and reproducibility of the review process. Inter-rater agreement was “almost perfect” for title and abstract screening (κ = 0.851, 95% CI: 0.78–0.92), with reviewers agreeing on 130 of 140 articles (92.9% agreement). The 10 disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Regarding articles for which only the abstract was available, we contacted the authors to provide us with the full text and included them in the analysis. For the remaining articles with abstract-only, we included them in the descriptive bibliometric analysis but not in the TCCM analysis, as the required data about theories, methodologies, and characteristics were not sufficient.

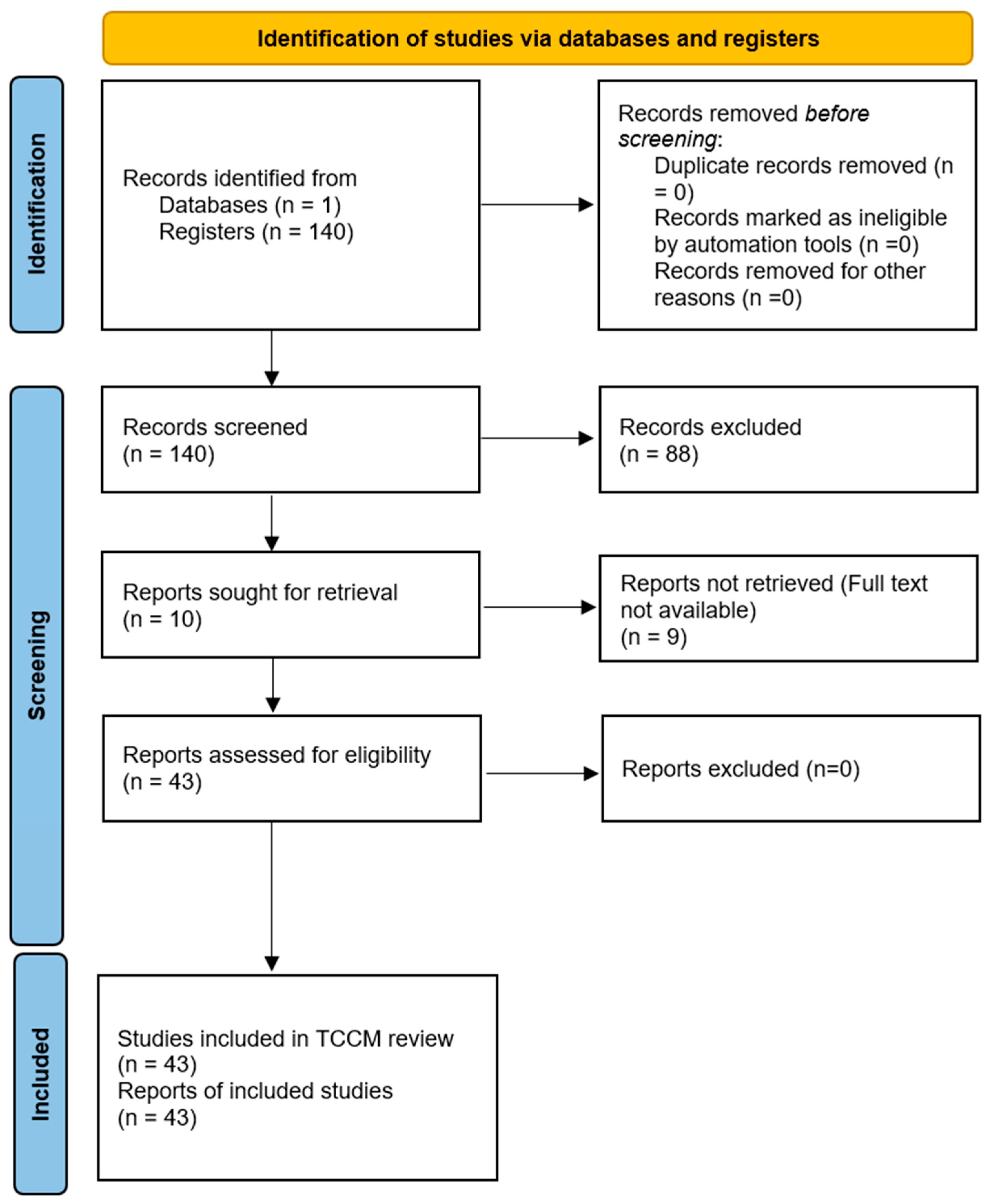

The entire selection process was carefully tracked and presented in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram presented in

Scheme 1 (

Page et al., 2021) and indicated the number of records identified, screened, included, and excluded at each stage. The full list of the selected articles that were used in the T-C-C-M analysis is presented in

Appendix A,

Table A1.

2.4. Coding and Review Process

During the full-text review phase, eligible articles were tracked and organized using a standardized form in Google Sheets, which included listing details (number of listing, Rayaan number assigned), publication details (title, year, authors, and country of author affiliations), and the features necessary for the TCCM framework described below. TCCM permits research teams to “establish connections between various complex relationships” (

Yeasmin, 2024, p. 3). We chose this particular framework because, as it has been shown, it makes reviews more impactful, and its effectiveness is demonstrated across marketing and consumer behavior domains (

Paul & Rialp Criado, 2020).

The coding process for the “Theory” component was systematically implemented through a two-step approach to ensure comprehensive analysis of both explicit and implicit theories involved and implied in the studies. This choice was grounded in recent research (

Schreiber & Cramer, 2024;

Newman & Gough, 2019) that highlighted the hidden theoretical assumptions that are not explicitly stated but exist in some studies, which need to be documented and interpreted. However, this choice comes with limitations that will be discussed in the respective section.

For the first step, we coded all explicitly mentioned theories that were directly referenced, named, or formally cited by the authors within the included studies. The second step involved a more interpretive analysis to identify implicit theoretical concepts and underlying theoretical orientations that were not explicitly named. This phase was initially subdivided into two components: (1) primary theoretical focus identification—we tried to identify the broader domain or orientation (e.g., psychological, social, commercial, etc.); (2) implicit theoretical concepts extraction—we documented the theoretical concepts that emerged from the studies’ research questions, frameworks, literature reviews, and variable relationships. This theoretical coding process helped us ensure that we recorded the formally used theories together with the implied theoretical foundations.

Responding to the reviewer’s comment, we took additional action for triangulation of the results with other studies to minimize bias. More specifically, first, we triangulated with articles published by the same authors to understand if, in other papers, they explicitly use a relevant theory. Second, we triangulated with other articles that cite the initial studies. In this step, we found all the articles of our study in Google Scholar, and then we studied all the cited articles that were published in English and were relevant to the initial study by including filters for words like “emoji” or “emoticon”.

As this step involved manual coding and interpretation, we incorporated the principles of

Thompson et al. (

1989) to minimize bias and make our subjectivity as transparent as possible. In this direction, we used a Gioia codebook (presented in

Appendix A,

Table A2) where we systematically put the second-order implicit concepts together with the first-order text parts from which we implied them, and then we tried to aggregate them to a theoretical concept or theory. Each article could have multiple codes. Interpretations were triangulated with the explicit theories extracted from the main body of articles.

If an excerpt was ambiguous for coders and we could not assign an implicit concept, we did not use it in the final analysis. If we were not able to extract any implicit concepts, we conservatively categorized the articles as “Atheoretical”. This happened in one out of the ten articles, included in

Appendix A,

Table A2.

However, even with these measures, we expect that bias inherently exists; thus, the results presented in the respective

Section 4.1.2 are subjective and may be treated as only one reading out of the multiple possible readings of the theoretical landscape in emoji research.

For the “Methodology” component of TCCM, we recorded the broader category of each research study and a sub-category that was developed with relevance to the primary category. For mixed methods studies, beyond the sub-categories, we also separately coded them if they included a field or lab experiment. In addition, for the experimental studies category only, we kept track of sample characteristics, such as gender, age/generation, and sample size.

For the “Context” component of TCCM, we recorded information about the marketing channel, platform, industry, and country of experiment/analysis. For the “Characteristics” component, and where applicable, we introduced the following fields to uncover emoji dimensions that are potentially important: (1) emoji type (face, object, gestures, symbols, and animals); (2) emoji function (emotional expression, emphasis, word replacement, and decoration); (3) emoji sentiment; (4) emoji placement; (5) emoji frequency; (6) emoji combinations; (7) independent variables; (8) dependent variables; (9) moderating variables; and (10) mediating variables.

In sum, we employed a carefully designed and executed screening and coding process to create a robust foundation for our analysis and future directions. The meticulous methodological rigor employed in this review, with the combined use of the TCCM framework, Prisma reporting, Rayaan screening, and coding in Rayaan and Google Sheets, hopefully ensures academic integrity, clarity, and transparency and is reproducible by other researchers.

3. Results of Bibliometric Review

3.1. Overview

For our bibliometric analysis and the publication trends, we performed the analysis in Google Sheets (Google LLC; Mountain View, CA, USA) and VOSviewer–Version 1.6.20 (Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands), a bibliometric software package that shows the relationships of the publication data. Because the scope of the bibliometric review is broader and we are trying to map the full field and the relationships of data, we included all 140 articles that Scopus returned before the manual screening process.

3.1.1. Publication Trends

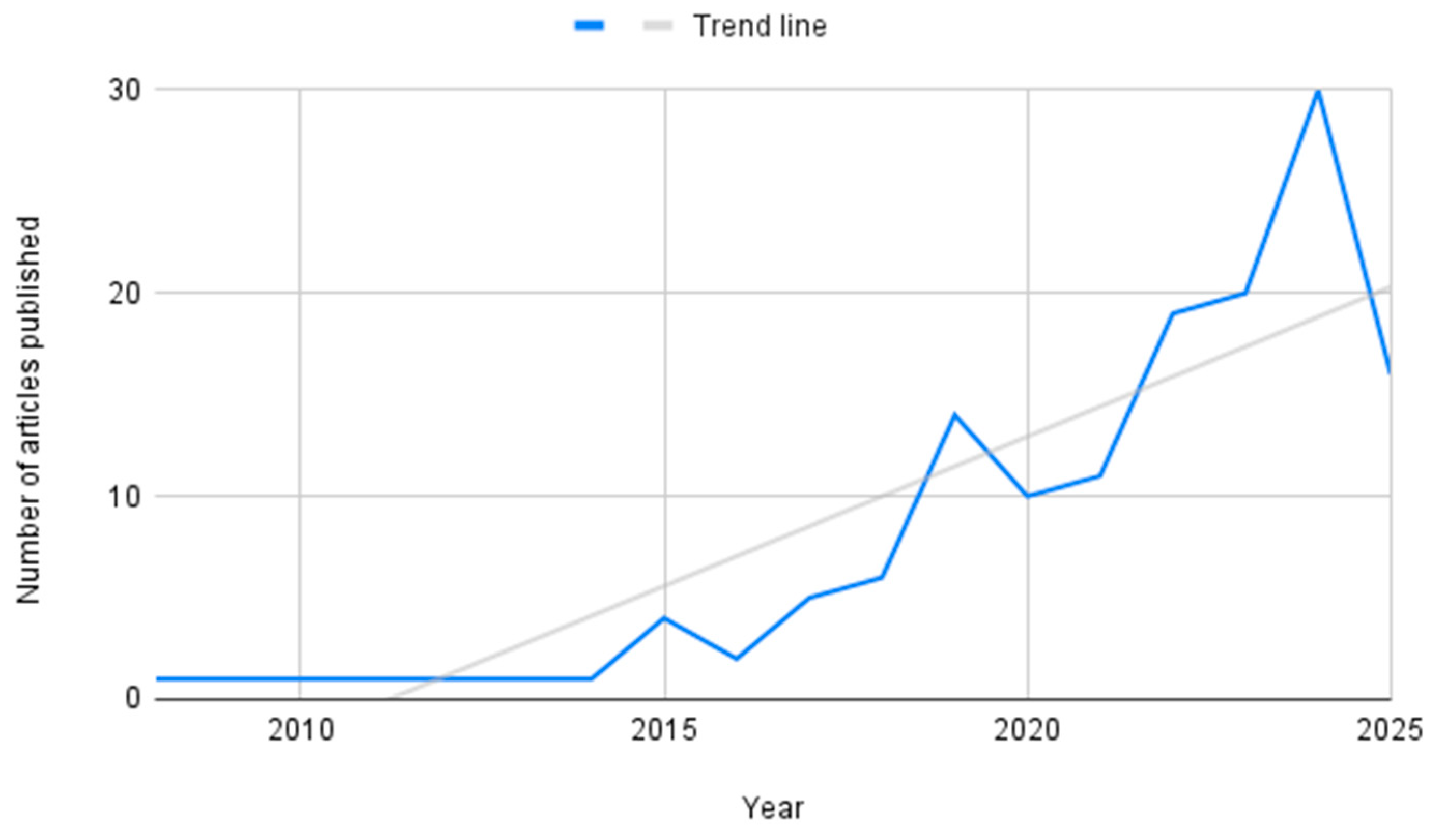

In

Figure 1, the annual publication trends are presented. First, it is clear that there was no emoji research in marketing before 2008. There is a clear separation between the early stages (2009–2014) with one study per year, a growth phase from 2015 to 2018, and an acceleration phase from 2019-today. The year 2024 was a peak year, and 2025 shows a decline because of incomplete data. In sum, emoji research in marketing and advertising is steadily growing, as the trend line shows.

3.1.2. Article Classification

Table 1 shows the 10 most cited articles with their authors, year of publication, and number of citations. The average number of citations of the 10 articles is 139 citations, while the average of all 140 articles is 20 citations, with a ratio of 7 to 1. These ten articles together account for 49.9% of the total citations, showing that they serve as the foundation in a field that is quickly evolving. Obviously, in the list we do not have articles published after 2020 despite their larger volume, which clearly shows a citation delay, probably because of long submission-to-publication periods.

3.1.3. Journal-Wise Classification

In

Table 2 we present the top 17 journals according to their number of articles in emoji research in the context of marketing and advertising. Approximately 44 articles are distributed between the top 17 sources, and the rest are dispersed among multiple sources. We notice that journals with a business, technology, and psychology focus appear in the list, depicting a landscape where emojis in marketing are viewed within diverse disciplines.

3.1.4. Conceptual Structure

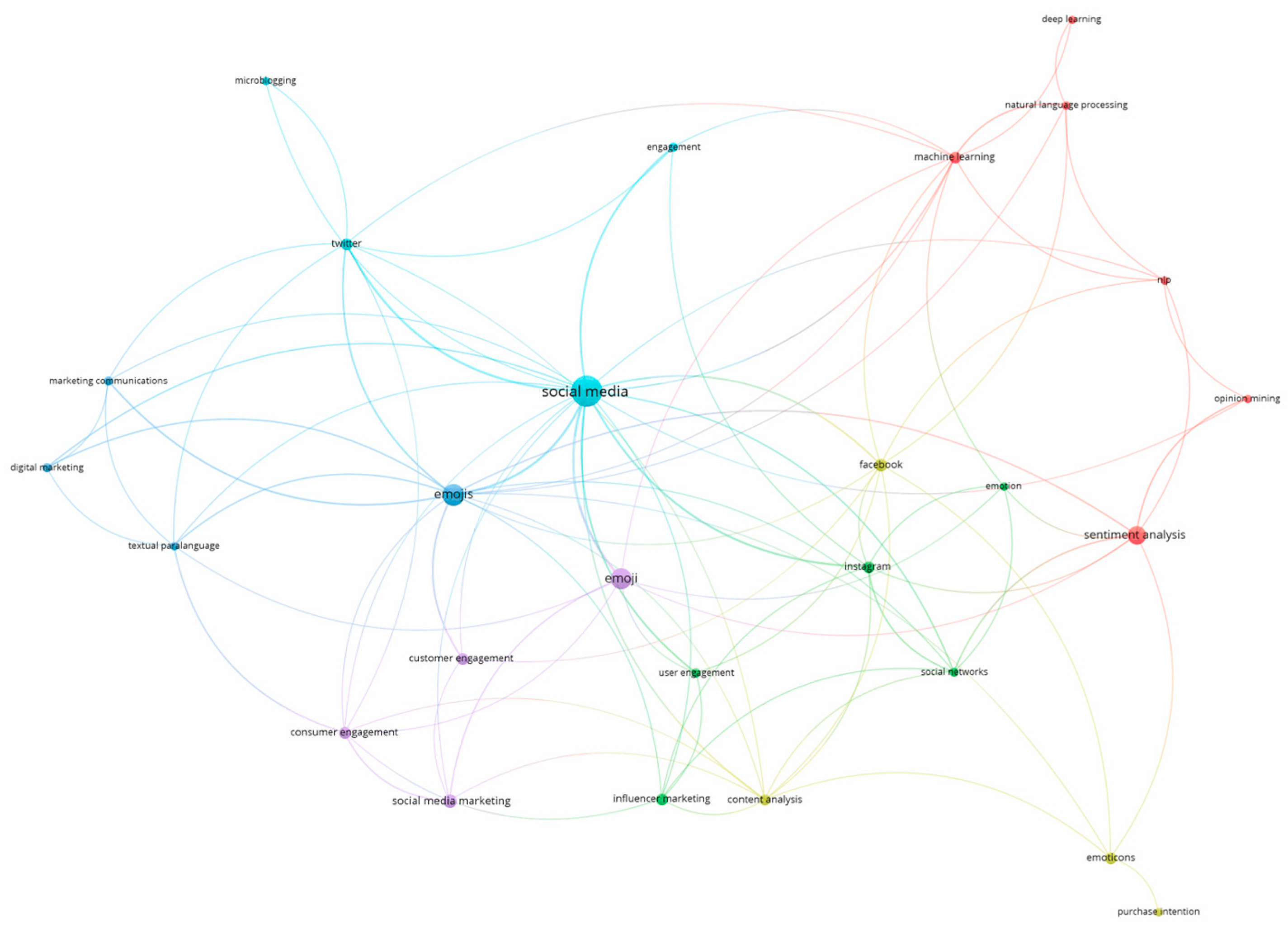

In

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, we see the keyword co-occurrence analysis of the field for all keywords (

Figure 2) and author keywords (

Figure 3). First, once more, we observe the

interdisciplinary nature of the field. In

Figure 2, the green cluster represents the business perspective (social media, digital marketing, and marketing communications), which seems to have a slightly central position, showing that the primary point of view in emoji research in marketing is commercial and with a focus on social media, the natural environment where emojis are used. The blue cluster has “human” at its core, representing the psychological aspects examined (e.g., perception, demographic variables), while the red group is more technology-focused, concentrated around terms such as “sentiment analysis”, “machine learning”, “data mining”, and “algorithms”.

In the same cluster, we see an interest in operationalizing emotional understanding with emojis in a social media context. Its proximity to the blue cluster shows that there is an effort to bridge the gap between traditional psychological research with technological advancements or that there are efforts in the classification of emojis based on their emotional aspects.

The yellow cluster in the middle of the graph summarizes the interdisciplinary nature of the field. Emojis are researched in marketing for their psychological and linguistic properties.

In

Figure 3, we present author keywords, and we notice the authors’ practical approach in keyword selection. There is now a higher emphasis on commercial aspects, as authors use keywords about specific platforms and commercial concepts, probably to make their research discoverable by marketers.

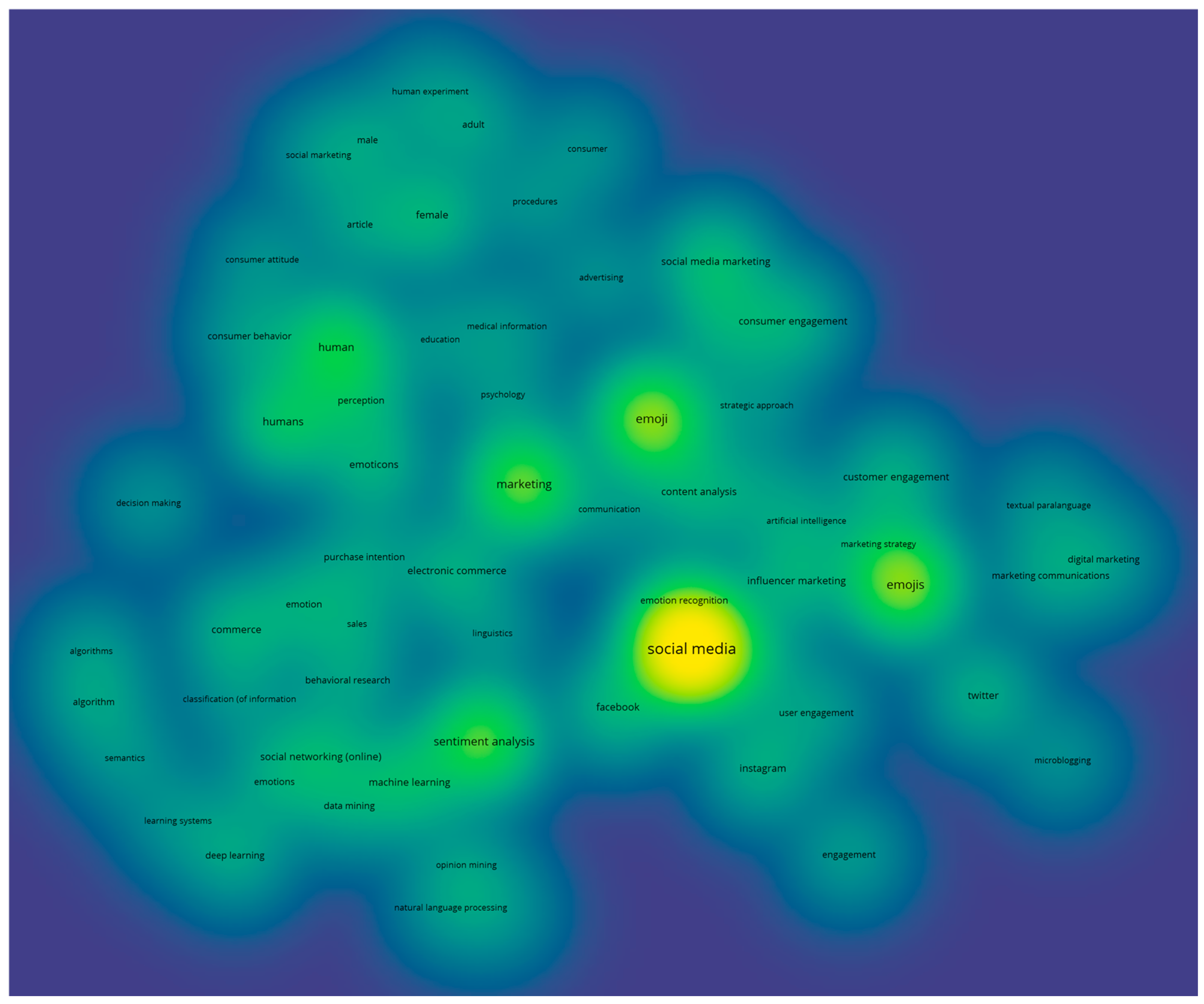

In the density heatmap presented in

Figure 4, differences between the keywords “sentiment analysis”, “emotions”, and “semantics”, in terms of the variety of keywords, their density, and distance, do not go unnoticed.

While emojis carry both emotion and meaning, it seems that there is a preference to study their emotional aspects (keywords: emotion, “emotion recognition”)

rather than their semantic ones (keywords: “semantics”, “opinion mining”), which further means that we have been focusing on an emotional rather than a cognitive point of view. Last, while we had a particular focus on advertising, we can notice its very low density and its distance from all other concepts, showing that it has received very little attention.

3.1.5. Country Analysis

The top--cited countries are presented in

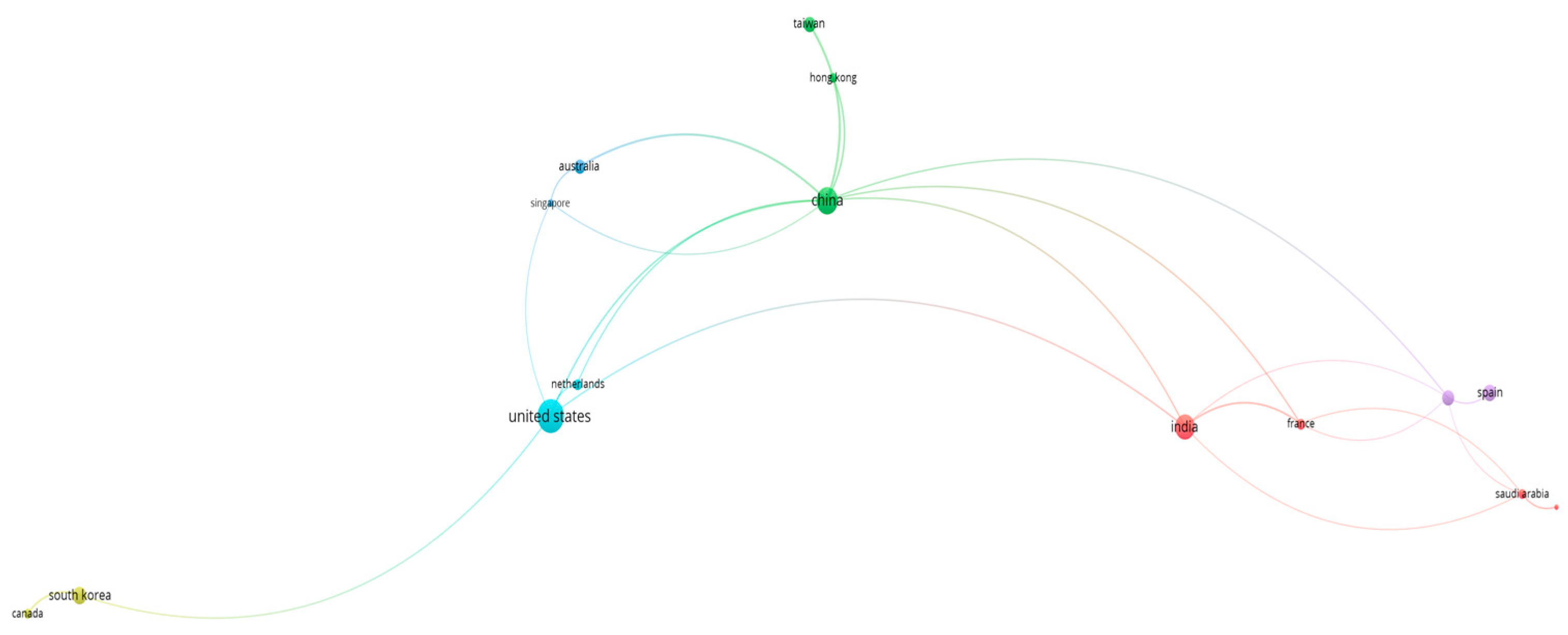

Table 3. The top three countries (United States, China, and India) appear to have the most impactful work, accounting for 52.86% of all countries in the dataset. We also notice equally distributed citations between European (United Kingdom, Netherlands, and France) and Asian countries (South Korea, India, Singapore, etc.), with smaller countries appearing to have opportunities for high citations.

Looking at the next graph of co-authorship (

Figure 5), we obtain a more comprehensive picture of country dynamics in the field. From the bigger nodes, we notice that authors from these countries have established collaborations, resulting in three clear clusters. From the above findings of the overview, the

United States was the most prominent in terms of citations, but India and China have a central bridging role with collaborations.

4. Results of T-C-C-M Analysis

4.1. Theoretical Perspectives (T)

4.1.1. Explicit Theories

Across the 43 studies, the analysis of the explicitly mentioned theories gave 52 different theoretical references, presented in

Table 4, indicating that some of the studies used multiple theoretical models and that researchers have been drawing results from diverse theories. A quarter of the studies (n = 10) were atheoretical, which is a pattern found before in consumer behavior systematic reviews (e.g.,

Bhardwaj & Kalro, 2024). There is prioritization of empirical findings over theoretical foundations, with 50% of the machine learning studies not using an explicit theory, while the more “traditional” content analysis studies prefer the standardized approach of grounding decisions in theoretical models.

The combination of atheoretical studies with a wide mix of theories used indicates that the field is still in its early stages of theoretical development and that there is not a single framework explaining the multitude of emoji characteristics in brand communication.

Our analysis of the most prominent theories used in the studies for our sample is presented below in

Table 4.

- (a)

Emotions as Social Information Theory (EASI)

The EASI theory (

Van Kleef, 2009) explains that the emotion conveyed and transferred by someone affects the behavior of the observer in dual pathways: inferential processes and affective reactions. The level to which the observer will be influenced by the two mechanisms depends on their information processing.

To our knowledge, there is only one study that has tested if the EASI theory is valid for emojis (

Erle et al., 2022), and it was partially confirmed, since the results showed that,

while the affective pathway had the same results as in face-to-face communication, the inferential pathway probably works in different ways. This second observation could be linked to the initial idea of

Van Kleef (

2009) that the inferential pathway works when the observant can accurately perceive the meaning.

One study (

Maiberger et al., 2024) confirmed the inferential pathway and found that using the facial emoji as a replacement increased ambiguity and thus hurt the inferential process. Another study (

Madadi et al., 2024) has found that emojis may make the meaning of the message more complex and hurt processing, and concluded that context moderates effectiveness.

- (b)

Media Richness Theory (MRT)

Media Richness Theory was originally developed by

Daft and Lengel (

1986) and categorizes media based on their capacity to process information, with richer media being more effective for complex tasks. MRT is used in a corporate context to give insights about platform characteristics that enhance or constrain corporate communication effectiveness. Under this theory, emojis promote richer communication and facilitate better processing. In the studies examined, MRT was mainly used in content analysis studies.

- (c)

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory (

Hofstede, 2011) was the only cross-cultural theoretical framework in our sample of studies. In our corpus, it was used in two studies employing content analysis but with contradictory results.

Neel et al. (

2023) found no interaction between nationality and emoji sentiment across three Western cultures (American, British, and Danish).

P. Wang and McCarthy (

2020), on the other hand, found cultural differences between Australians and Singaporeans for different message types. These contrasting findings imply that

different cultures perceive corporate messages in different ways, but sentiment is more “universal”.- (d)

Emotional contagion

The emotional contagion theory (

Hatfield et al., 1992) is based on the idea that people, from their infancy, “tend to mimic facial expressions… of those around them”, and through that automated copying of expressions, “they catch other people’s emotions” with “complex cognitive processes” (p. 154) but also with unconscious mechanisms. While it was applied for the positive effect of facial emojis (

Das et al., 2019), it cannot explain why emojis bring emotions to users.

- (e)

Other studies

The use of 29 theoretical frameworks indicates that to understand the multiple traits of emojis, we need to rely on psychology, cognitive theories, and relationship marketing. There is a notable absence of widely used theories in consumer behavior research, such as the Stimulus-Organism-Response model and the Theory of Planned Behavior. This choice is rationalized because of the focus on the immediate outcomes of emojis.

4.1.2. Implicit Theories

Among the 11 atheoretical studies, triangulation (

Appendix A,

Table A2 and

Table A3) has revealed that 5 studies were atheoretical and seven frameworks were used: Affective Science/Emotional Contagion (n = 2), Construal Level Theory (n = 1), Elaboration Likelihood Model (n = 1), Information Processing theories (n = 2, one linked to content complexity), and Anthropomorphism (n = 1, explaining effects via human face resemblance).

In the mix of explicit and implicit theories, we now see a more balanced approach to affective and cognitive frameworks, a finding that is in line with researchers’ choices about mediators, presented in 4.3. Results are discussed in

Section 5.1.

4.2. Context (C)

4.2.1. Geographic Distribution

The field is geographically spread across 21 countries, yet there are some dominant forces, namely the United States and China, reflecting their broader focus on consumer behavior research (

Scopus, 2025). South Korea shows a strong focus on the field of emojis, probably because of its technology-driven research culture and a clear direction towards collaboration between the industry and institutions (

Chung et al., 2022;

Cho, 2014). The presence of five multi-national studies reflects the need for cross-cultural comparison (

Appendix A,

Table A4).

Despite preliminary findings about universal emoji usage in three Western countries (

Neel et al., 2023), there is also contradictory evidence about significant differences across cultures and countries. For example, the study by

P. Wang and McCarthy (

2020) found that there are cultural differences in the perceived credibility of the source in Australian and Singaporean audiences.

4.2.2. Industries

From an industry perspective (

Appendix A,

Table A5) there is also remarkable diversity. The prevalence of the travel industry could be owed to the general growing interest in tourism marketing in the last years (

Scopus, 2025) or to the more emotional side of the industry, ideal for leveraging the emotional and anthropomorphic properties of emojis that enhance the message and influence consumer behavior (

Hosany & Prayag, 2013;

Ramos et al., 2013;

Walters et al., 2012;

Han et al., 2019;

Christou et al., 2020;

Ding et al., 2022). In this corpus of studies, emojis seem to have only favorable results in terms of user engagement, hotel selection, and eWom (

Hsu & Chen, 2020;

P. Wang & McCarthy, 2020;

Orazi et al., 2023;

X. Wang et al., 2023a;

J. Yu et al., 2024). However, effectiveness may be lower for premium/luxury hotels. Research in this sector has uncovered the need to select emojis that are congruent with the topic and type of content.

In electronics, interestingly, we have limited attempts to replicate the work of

Das et al. (

2019) with the same product (digital camera), while many studies from our sample have used the work of Das et al. as the foundation for their work. Results about the effect of emojis on purchase intention are contradictory.

Surprisingly,

the fashion industry is underrepresented despite the growing research interest in fashion marketing, especially in the past two years (

Scopus, 2025). Given its hedonic nature and the role of emotion in it, we expect to see more studies about emojis in fashion marketing (

Bishnoi & Singh, 2022;

Chan et al., 2015;

Zahari et al., 2022). A similar note must be made for the beauty industry, which is inherently emotional due to its hedonic nature (

Hashem et al., 2020;

Radhi et al., 2024;

Diwoux et al., 2024;

Courrèges et al., 2021).

Traditional sectors (e.g., furniture, real estate, automotive, and services such as telecommunications or insurance) and emerging ones (e.g., fitness/wellness, entertainment) are not explored, a finding probably owed to the small sample and the lower volume of research in these fields.

The significant portion of studies (seven cases) without specific industries suggests that emoji research transcends industry boundaries or focuses on general consumer behavior patterns.

4.2.3. Marketing Channels and Platforms

More than half of the studies are located in a social media context, and there is a substantial body of literature without a specific channel. Research seems to focus more on general emoji principles than on channel-specific applications (

Table 5).

There is also

notable underrepresentation of “Advertising” (not including social media advertising). It could be owed to technological or resource barriers such as restrictions on platforms not allowing advertisers to use symbols (

Google, n.d.), or financial resources and industry partnerships needed to run field experiments.

Email marketing is also underrepresented, a finding that is particularly puzzling because conducting field experiments would be easy and less expensive, as platforms like Mailchimp give marketers multivariate testing tools (

Vardikou et al., 2025a).

The finding that most of the studies did not focus on a specific platform reinforces the idea that emoji research in marketing communication is still in its infancy, trying to build basic knowledge. As the field progresses, we may see more refined approaches with specific platform focuses.

In

Table 6, we observe a focus on social media on the three platforms that represent the core of the social media ecosystem: Twitter/X (combined), Facebook, and Instagram. The first position of Twitter/X is surprising, given that it is not the biggest platform worldwide, and could be explained by accessibility to its academic-friendly API until 2023, which gave researchers free access to data (

Coalition for Independent Technology Research, 2025).

On the other hand, Facebook, the leading platform worldwide in user base (

Statista, 2025), has accessibility barriers, as it required researchers to apply to the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research ICPSR (

Meta, 2025b). Moreover, its dedicated platform Crowd Tangle was deactivated in 2024 (

Meta, 2025a), making data acquisition even more complex. A limited representation of emerging platforms like TikTok (one study) suggests a delay in capturing the trends and in publishing.

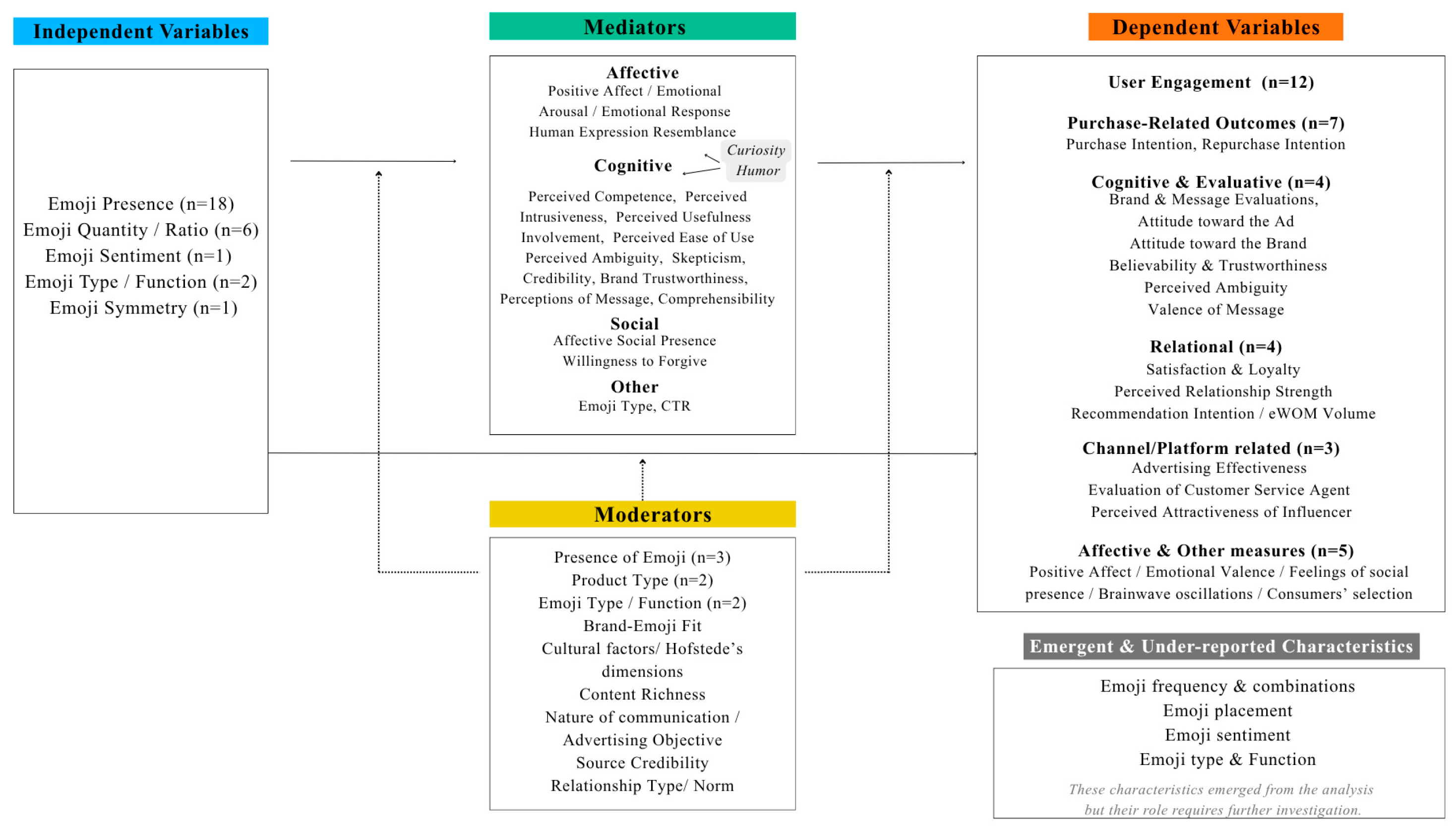

4.3. Characteristics (C)

A conceptual framework is developed to categorize the variables identified in the analysis. Alongside the traditional relationships (independent/dependent variables, moderators, and mediators), we present other emoji characteristics that emerged in our analysis and that could potentially serve as independent variables or moderators. The key variables are presented in

Scheme 2.

We consider the findings in

Section 4.3.8, the

“anthropomorphic bias” towards the selection of facial emojis and the

“positivity bias” towards the selection of happy emojis, to be two compelling findings in this section.

4.3.1. Independent Variables

Our analysis of independent variables, presented in the

Appendix A,

Table A6, revealed diverse characteristics and a striking pattern.

Emoji presence/absence was the dominant independent variable, and most studies agree that the presence of emojis brings the desired consumer responses and evaluations. Emoji presence has been linked with higher post engagement (

Taba et al., 2023), affect transfer (

Das et al., 2019;

Smith & Rose, 2020;

Neel et al., 2023), feelings of social presence, and positive evaluations (

Park & Sundar, 2015). They have also been linked to customer selection when they are presented as subliminal cues for 1 millisecond (

Hsu & Chen, 2020).

There is no consensus on whether the presence of emojis is linked with higher purchase intentions. Even for the same hedonic product and in the same context of sponsored ads, emoji presence can be linked with higher purchase intentions (

Das et al., 2019) or lower purchase intentions when the ad is perceived as more personalized (

Lee et al., 2021). It seems that the relationship is moderated by the valence of emotion (

Das et al., 2019;

Mladenović et al., 2022).

Given the limited focus on advertising and the methodological differences in the studies, the replication of such experiments for hedonic and utilitarian products would be beneficial to uncover the dynamic. However, when measuring valence, it seems that users’ self-reports of valence may differ from implicit biometric measures (

Rúa-Hidalgo et al., 2021).

There is contradicting evidence that emojis may bring negative responses, for example, by hurting seriousness and authenticity (

Madadi et al., 2024). Additional research would be necessary to understand if the self-reported measures match the real responses.

Next, we see a

clear quantitative focus on independent variables such as the number of emojis, number of facial emojis, and the emoji ratio. A higher number of emojis has been linked with higher review trustworthiness (

Huang et al., 2021), while on Twitter, there seems to be an optimal number from 0 to 3 emojis, as a higher number decreases engagement (

Guzmán Ordóñez et al., 2024), and in other studies, there was no effect of the emoji ratio on engagement (

Yang & Shin, 2021). So far, it seems that “more is not better”, and we need to study the optimal emoji ratio.

Some other studies explored the categorical aspects of emojis, indicating

interest in exploring how different categories of emojis function. Non-facial emojis seem to increase eWom volume (

Orazi et al., 2023), and asymmetrical facial emojis are linked to higher user engagement because the human expression resemblance is higher (

Hewage et al., 2021). In the context of customer service recovery, emojis with a negative sentiment may lead to higher satisfaction and repurchasing behavior (

Ma & Wang, 2021).

Also, we notice a small percentage of studies have an independent variable not related to emojis, probably showing initial efforts to understand antecedents of emoji usage or emoji reactions. More details will be presented in the respective sections of moderators and mediators.

The above findings reinforce what is also mentioned in other parts of our analysis, that the field remains in an exploratory phase where basic effects from emoji presence and emoji numbers are tested.

4.3.2. Dependent Variables

We employed a two-stage approach for the analysis of dependent variables. We first documented all dependent variables (

Appendix A,

Table A7), and we created a consolidated table (

Table 7) based on similarity and conceptual coherence so that the broad categories are clear, while maintaining granular information.

User Engagement/Consumer Engagement

The primary category of dependent variables is User Engagement/Consumer Engagement (34.29%), showing a focus of marketing researchers on the effects of emojis in user interactions with content. Based on the synthesized evidence, emoji usage produces mixed but generally positive effects on user engagement.

Posts with emojis receive more likes Taba et al. (

2023) and TikTok videos with emojis

are shared more (

Einsle et al., 2024).

However, findings indicate that

emoji effectiveness depends on strategic factors including emoji selection, content type, quantity, content placement, and source credibility. The selection of the right emoji or emoji category for the content type is important, as the same emoji brings different results when placed in different topics (

X. Wang et al., 2023a,

2023b;

J. Yu et al., 2024). For example, engagement is higher when emotional emojis are used with aesthetic content and when semantic emojis are used in promotional content (

X. Wang et al., 2023a)

In contrast, in some cases, emojis decrease engagement, for example, by

making diversity and inclusion posts less effective (

Bombaij & Mokarram-Dorri, 2024), by decreasing open rates in email marketing when they are artifact emojis (

C. H. Kim et al., 2024), or by affecting

how users perceive message sources (Balaji et al., 2023), and they make firm-generated content less effective compared to employee-generated content. Generally, authors grounded this result in the loss of expertise or the increase in skepticism.

Purchase-Related Outcomes

The second category (20%, n = 7) of dependent variables is Purchase-Related Outcomes. This finding is aligned with results from keyword analysis (

Section 3,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Given the underdevelopment of the field, it seems to be a theoretically premature emphasis.

The analysis showed that emojis mostly

bring higher purchase intention because, firstly, they increase trust and consumer engagement (

Duffett & Maraule, 2024) and

secondly, they increase positive affect, but this result is valid for hedonic and not utilitarian products (

Das et al., 2019;

Mladenović et al., 2022). Interestingly, most of these studies focused on Generation Z, indicating a research gap.

We also have totally contradicting evidence for the same product (camera), where emojis bring lower purchase intentions (

Lee et al., 2021), calling for the replication of these studies in field experiments. Another interesting study in a gift-giving setting (

Huang et al., 2021) had mixed results on purchase intention, in that facial emojis had stronger effects on purchase intentions only in communal (versus exchange) relationships, meaning only when the gift giver does not expect something in return. All the above findings indicate that additional research is necessary on the factors affecting the relationship between emojis and purchase intention, as

the context of the purchase matters, and relationship dynamics could also play a role.

Specialized Measures

Specialized measures (brainwave oscillations, construal level, difference between implicit and explicit measures of valence, feelings of social media presence, etc.) are dependent variables in 14.29% of the studies. This sophistication could also be explained by the presence of multiple studies exploring emojis in a psychological context without a marketing focus (

Bai et al., 2019;

Kaye et al., 2017;

Riordan, 2017a).

As the work of

Hsu and Chen (

2020) suggests, emojis used repeatedly as subliminal cues for 1 millisecond can bring positive consumer responses (hotel selection). Linked to the above, this work paves the way for

the use of neuroimaging tools to understand hidden responses that precede engagement and purchase intention.

Other variables

Consumer preferences and evaluations are mostly positively affected by the use of emojis, but results are fragmented. Review trustworthiness is positively affected by a higher number of emojis (

Huang et al., 2021), consumers’ selection of hotels is positively affected by the subliminal presence of a face emoji (

Hsu & Chen, 2020), and evaluation of communication with employees of the company and influencer attractiveness are also positively affected by the presence of emojis (

Park & Sundar, 2015;

Balaji et al., 2023;

Guo & Wang, 2024).

In an interesting study (

Boman et al., 2023), emojis with a dark skin tone have led to higher consumer preference of conservative brands through higher brand advocacy.

In sum, the distribution of dependent variables in emoji research shows, firstly, pluralism and secondly, a strong practical focus on short-term behavioral outcomes (user engagement and purchase intentions). As knowledge progresses over time, we expect to see more studies with a long-term focus on the relationship impact of emojis rather than direct user engagement.

Findings have revealed that emojis bring generally positive effects on user engagement, purchase intentions, and consumers’ evaluations and preferences, but this effectiveness is highly dependent on the context. Contradictory findings for the same product imply methodological differences that have to be addressed in the future.

4.3.3. Moderators

Nearly

half of the studies explored had no moderating variables at all, and most of the studies focused on basic factors, such as the presence/absence of emojis, emoji combinations, product type (utilitarian/hedonic), and presence of a profile picture (

Appendix A,

Table A8).

The

presence of emojis has been found to act as a moderator between the content and its effectiveness, for example, by moderating the relationship between the valence of content and the effectiveness of advertising through the reinforcement of positive thumbnail effects and of negative title effects (

Li et al., 2022) or between the message source (employee-generated vs. firm-generated content) and social media engagement and trust (

Balaji et al., 2023).

In cause-related marketing, emoticons attenuate the interaction between the donation size and construal level (

Yoo et al., 2018), and they also reduced the perceived monetary sacrifice and increased positive responses. This finding creates opportunities for emoji usage in cause marketing. However, the above results are valid for emojis that complement the text, as emojis that replace words have been linked to low effectiveness (

Maiberger et al., 2024).

As already discussed, context matters in emoji effectiveness. Regarding the product type, hedonic products present increased effectiveness with emojis (

Mladenović et al., 2022;

Das et al., 2019). The product type has been previously found to moderate consumer behavior variables’ relationships (see

Ren & Nickerson, 2019;

Kivetz & Zheng, 2017). Referring to

Section 4.2 and excluding the food industry (three cases), which is both utilitarian and hedonic (

Coimbra et al., 2023), we see a balanced distribution, aligning with recent neuroscientific data showing that, in both types, there are emotional responses from consumers (

Bettiga et al., 2020).

Variables related to relationships and the brand have also served as moderators. For communal (versus exchange) relationships, the effect of emojis in the positive affect, customer satisfaction, and repurchasing behavior is higher (

Smith & Rose, 2020;

Ma & Wang, 2021). Emojis provide less benefits to premium sellers (

Orazi et al., 2023), and there seems to be a brand–emoji fit, a campaign objective–emoji fit, and a content–emoji fit that moderate effectiveness (

Rúa-Hidalgo et al., 2021;

X. Wang et al., 2023a;

C. H. Kim et al., 2024), indicating that the congruence of the emoji is important.

However, congruence should be further explored, as it may have even more types, such as semantic, emotional, and cultural. Interestingly, the only study exploring nationality as a moderator found no differences between three Western countries (

Neel et al., 2023).

4.3.4. Mediators

Results from the analysis of the mediating factors are presented in the

Appendix A,

Table A9. Again, more than half of the studies (57.1%) explored no mediating variables, which reveals a

critical methodological gap.

In the rest of the studies employing a mediation relationship, we observe more affective and cognitive factors and less social and ideological factors. Affective factors, from the more generic positive affect to the more specific emotional arousal, show a primary recognition that emojis bring desired results through emotional pathways, consistent with the EASI theory and emotional contagion theory.

Suppressing

cognitive mediating factors include processing fluency, comprehensibility, skepticism, perceived competence of the brand, and childishness and trustworthiness of the brand (

C. H. Kim et al., 2024;

Orazi et al., 2023). It seems that cognitive responses may be considered better fits as mediators in cases of semantic emojis, but this finding has to be further explored because it relies on a dichotomy between emotional and semantic aspects that may not exist (

X. Wang et al., 2023a).

Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and involvement with emojis may also serve as enabling cognitive mechanisms that explain the positive relationship of emojis with purchase intentions but given the limited sample with only South African Generation Z people, additional research is necessary (

Duffett & Maraule, 2024). Perceived intrusiveness was not confirmed as a constraining mediator between emoji usage and purchase intentions (

Lee et al., 2021).

Up to here, we realize that the two pathways of the EASI model have been explored in a scattered and non-cumulative way, with a focus on the affective pathway as enabling and on the cognitive pathway as a suppressing mechanism. There is only one study that explores cognitive variables as facilitating mediators, and there are no studies about the suppressing role of affective variables.

There is also some evidence that emoji effects are treated as social phenomena (20%), for example, by employing mediators such as affective social presence, perceived sincerity, and willingness to forgive.

What is notable in the analysis of the mediators is the absence of variables central to the most prominent theories, indicating an isolation from theory. Also, there is very limited focus on attention, comprehension, and memory as variables that could mediate the effect of emojis on user engagement.

Taken together, the analysis of moderating and mediating variables reveals a field where more than half of the studies do not explore moderating or mediating relationships and the other half is scattered across many different variables without replication and mostly consistent with basic factors such as emoji presence or product type.

4.3.5. Emoji Frequency and Emoji Combinations

Our analysis of the emoji frequency (how many emojis are tested), where it was available (n = 13), uncovered that most studies either use a single emoji (53,85%) or multiple emojis at the same time (23.08%). While frequency has received extremely limited attention from researchers so far, it seems that more emojis could hurt the perceived competence of the brand but improve the trustworthiness of reviews (

Orazi et al., 2023;

Huang et al., 2021).

A contradictory finding is that users find emoji combinations, especially rare ones, very interesting (

Guo & Wang, 2024;

X. Wang et al., 2023b). These findings are puzzling, given that two of these studies are for the same product category (accommodation). A possible explanation for the discrepancy lies in the methodological choices, with the study of Orazi et al. employing large scale field data and experiments, while Guo and Wang had a qualitative approach.

4.3.6. Emoji Placement

Regarding placement, presented in

Table 8,

over half of the studies that report where the emoji was placed have put it at the end of the sentence. In fact, there was not a single case where the emoji was used at the beginning of the phrase, and the question remains whether findings about the effectiveness of emoji presence and emoji frequency would be valid if the emojis were placed at the beginning or even in the middle of the sentence.

Previous results reported in linguistics research show there is a semantic benefit when emojis are sentence-final (

Grosz et al., 2023), but at the beginning of the phrase, they could serve as emotional primers (

Dai et al., 2024).

Moreover, while previous studies generally agreed that emojis are better processed when they act as a supplement than a replacement of words, in our corpus of studies, there is a case (

C. H. Kim et al., 2024) with contradicting evidence showing that artifact emojis worked better when they replaced words; otherwise, they increased skepticism. Finally, while

almost all studies used the emoji alongside the text, there was one case with a different approach, where the emoji was used in a video and as a subliminal cue.

4.3.7. Emoji Sentiment

Despite the primary focus of emojis as emotional cues, few studies (n = 11) reported the selected emoji’s sentiment (

Table 9). There is

a clear positivity bias explained by the focus on user engagement and purchase intentions and by a culture bias or a publication bias. The underlying reasons could be rooted in an industry practice that promotes positive content (

Pınarbaşı & Kırçova, 2021;

Casado-Molina et al., 2022).

The only study experimenting with positive and negative sentiments, in the context of service recovery, has found that negative emojis bring higher satisfaction and repurchasing behavior (

Ma & Wang, 2021), giving preliminary insights against the positivity bias and

opening the door to research in negative circumstances.

4.3.8. Emoji Type and Function

The emoji type (face, objects, etc.) was recorded whenever it was available and is presented below in

Table 10.

The most frequent emoji type used in research is by far the facial emojis, with an impressive 62% testing only facial emojis. It seems that

emoji research has still not recognized the diversity of emojis.

Facial emojis, due to their resemblance to human faces, have human properties and could also be used as priming cues, as we are wired to detect faces (

Weiß et al., 2020). Similarly, they are perceived differently in the text compared to non-facial emojis (

Cao et al., 2024), and while they can both carry emotions, we have not yet uncovered the dynamics (

Riordan, 2017b). A question remains as to whether we can extend the findings on non-facial emojis, especially the ones about affect. Would the EASI theory be valid for non-facial emojis? Implications are discussed in the future directions section.

Dominance of the emotional expression function is observed. Two shortcomings are that, first, there were no studies exploring only the semantic aspects of emojis (i.e., their role in enhancing the meaning of the text) or the navigational/emphasis/decoration aspects, and second, the limited sample of comparative studies constrains the picture we have so far. Results are presented in

Table 11. This finding reveals a

potential anthropomorphic bias.

Data about worldwide emoji usage shows a significant gap between research and practice, with popular non-facial emojis being underrepresented in marketing research. (

Unicode Consortium, n.d.;

Emojipedia, n.d.).

How is this gap explained? Since data about emoji usage do not discern between brand or consumer use, a possible explanation is that brands do not necessarily follow the same patterns in emoji usage as users, and this is then represented in emoji research. Additional data about emoji usage patterns from brands—and a comparison with user data—is needed, but there is some initial evidence that the above assumption is true (

Pınarbaşı & Kırçova, 2021;

Casado-Molina et al., 2022).

Additional research would uncover if brands use facial emojis more (in line with researchers’ choices) and if emotional expression is the primary reason why emojis are used in brand communications.

The key findings of the above analysis of characteristics are presented in the

Appendix A,

Table A14, alongside implications for future studies.

4.4. Methodology (M)

4.4.1. Category of Methodological Designs

The analysis of the methodological choices in

Table 12 shows that

the field has favored an experimental approach to test the effects of emojis on specific consumer behavior dimensions. The use of mixed methods shows a more refined approach combining multiple studies to better understand emojis with triangulation. The above findings indicate, first, that research on emoji usage in a digital marketing and advertising context is still in its infancy, and second, effort has been put into understanding if results from psychological and linguistic studies about emojis can be linked to their marketing effectiveness. Lastly, the presence of only one longitudinal study potentially means that emojis are perceived by researchers as having only short-term implications. These observations, together with the limited use of survey and questionnaire studies, suggest that we mostly try to understand how consumers respond to them but not “why” they respond in a particular way.

4.4.2. Sub-Categories of Methodological Designs

The sub-categories for the three dominant categories are presented in the

Appendix A,

Table A10,

Table A11 and

Table A12. The emphasis on online experiments (30,8%) and lab experiments (23,1%) and the limited use of complex approaches suggests that

emoji research in marketing is still in its formative years and suggests opportunities for more refined designs, where qualitative studies explore emoji perceptions and then quantitative studies test the findings.

For content analysis, researchers seem to prefer human over automated analysis, probably because of the subtle nuances and the multiple roles of emojis (semantic, symbolic, and emotional), or because there are not enough classification systems or theoretical frameworks for categorizing emoji usage.

The notable underrepresentation of field experiments and their combination with other experiments in mixed studies show that they are mostly used as confirmatory methods.

In sum, the analysis of the methodological choices suggests fragmentation. On the positive side, the field promotes controlled experimental designs to uncover causal relationships and mixed methods to triangulate and build robust results.

Some concerning patterns also emerge. The limited focus on survey studies, together with a minimal presence of qualitative studies, shows a low interest in understanding the “why” behind the effectiveness of emojis, and the minimal presence of longitudinal studies shows an emphasis on the immediate returns rather than on the sustained effects.

4.4.3. Sample Characteristics

Analyzing the sample of experimental studies, we found several limitations that constrain the generalizability of the findings. While the most common cluster is around 100–400 participants, sample sizes varied drastically (

Appendix A,

Table A13) because of the different experimental procedures, resulting in inconsistent findings.

We notice a

bias toward younger participants (18–39), with several studies only working with Generation Z. The reason may be that they are heavy users of emojis, or the emphasis is a result of convenience samples, as researchers are working with university students who are easier to be recruited (

Ashraf & Merunka, 2016;

Vinson & Lundstrom, 1978;

Jones & Sonner, 2001;

Fuchs & Sarstedt, 2010). The need for multiple samples has been recorded on many occasions (

Espinosa & Ortinau, 2016), and it is crucial to focus on other generations, as emojis can be interpreted in different ways by different generations.

The vast majority of designs relied on binary gender categories and had mostly female samples. Only one study (

Neel et al., 2023) explicitly included LGBTQ+ participants, showing that there is space for more inclusive sampling.

All the above patterns collectively indicate a field that needs theory development, methodological sophistication, and a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationships of emojis with consumer behavior variables.

5. Discussion and Future Research Agenda

In an effort to create a more comprehensive view of the TCCM findings, we created a framework depicting the current state of the field and the direction of future studies. It is presented in

Scheme 3.

5.1. Theory Development

Our analysis revealed some theoretical gaps that are acknowledged in this section. With nearly 25% of studies lacking theoretical grounding and with 52 explicit theories identified in 46 articles, the need for theoretical integration is evident. Our most compelling finding here is the Implicit Theory revealing the hidden theories of atheoretical studies. Based on the analysis, we then propose a theoretical integration.

While the EASI theory and emotional contagion theory have received the most attention from researchers, taking into account both explicit and implicit theories, our suggestion is to test the EASI theory in more design settings and with the intention to discover how the two mechanisms (inferential or affective) work for emojis. The reason is that the emotional contagion theory works more in automated, primitive ways and cannot explain why emojis bring the desired effects.

Given the focus of studies on how the presence of emojis is linked to consumer behavior, the choice of the emotional contagion was justified, but in the future, where more complicated research hypotheses must be tested, we posit that the emotional contagion theory is not enough to explain the mechanisms under which emojis work.

Given that in some cases we found contradictory findings, the EASI theory would be beneficial to address gaps. We would like to explain two indicative cases. First, from our analysis of dependent variables (see

Section 4.3.2), we noticed the contradicting results of emojis when it comes to Purchase-Related Outcomes for the same product in different contexts (lab experiment and field experiment in Facebook ads) (

Das et al., 2019;

Lee et al., 2021). Under the EASI theory, the discrepancy would be explained by the perceived appropriateness, a core variable that has been found to serve as moderator in EASI (

Van Kleef, 2009). Second, in the study of

Huang et al. (

2021), emojis had mixed results on purchase intention of gifts for different relationships. Relationships would be the moderator of the perceived appropriateness and of the relative strength of the pathways.

Upon reflection of the examined studies and more, the questions remaining are as follows: Is the EASI theory valid for non-face emojis that convey emotions (e.g., hearts)? Can the EASI theory be used to explain actual outcomes such as user engagement and purchases? How does the product type or the product message interplay with the affective and inferential pathways? What other model can explain the use of emojis in marketing and advertising, especially when there is no emotion conveyed (e.g., in pure symbols)? Regarding the emotional contagion theory, the largely automatic process implied leaves the mechanisms vague and, thus, are not easily tested.

Media Richness Theory could be used in other settings beyond content analysis. While the start may be to compare no-emoji versus emoji conditions, since emojis can enhance the text in various ways (symbolic, emphasis, semantic, and emotional),

more complex designs are necessary to define richness for emojis, measure it, and explain which properties of the emoji usage add richness. Under MRT, emojis make communication rich and facilitate processing. However, other research (

Barach et al., 2021) has found contradicting evidence that emojis do not always bring faster processing, and semantic congruence has to be carefully examined.

The role of culture has received minimal attention so far. This is a clear research gap that could be addressed by future studies, especially because Western, individualistic countries are commonly used for emoji research. While there is evidence that emojis, similarly to basic emotional expressions, may be interpreted universally across cultures, there are also cases where cultural dimensions influence consumers in complex ways (

Neel et al., 2023;

P. Wang & McCarthy, 2020).

Upon reflection on the above-mentioned theories, we found it fascinating that the notion of ambiguity, central to MRT and EASI, was also found in the implicit theories analysis. Ambiguity could also be linked conceptually to Hofstede’s dimension of “uncertainty avoidance”. Taken together, we have a beautiful theoretical convergence around ambiguity that could drive more integrated research on questions such as the following: (1) How do brands in high versus low uncertainty avoidance cultures differing in their emoji use? (2) When using emojis in marketing, how do we define ambiguity? Are there different types, such as emotional/semantic ambiguity, that reflect the multiple roles of emojis? (3) Which emojis are the least ambiguous across cultures? (4) How and when do emojis reduce (or increase) the ambiguity of the marketing message? (5) How can the emotional contagion theory, which relies more on an automated process, be used to explain the role of emojis in ambiguity?

As some of the aforementioned theories complement each other and some are completely different in their approach, we created

Table 13 to map theories involved in our corpus of studies, how they contribute to emoji research, and their limitations.

We propose EASI as the main framework in emoji research. Because of its dual pathways that match the two main functions of emojis, emotional and semantic, it has the potential to explain emojis, and, thus, we explore the possibilities of its integration with other theories in the same table below. Future research could test these possibilities.

5.2. Context

Regarding the context of future studies, our analysis suggests that there are opportunities for a deeper look in more industries, marketing channels, platforms, and cultural settings.

5.2.1. Industries and Product Type

As research about emojis progresses, the underrepresented industries (fashion, beauty, e-commerce, etc.) and the industries not appearing in our sample (automotive, services like insurance/telecommunications/energy, fitness/wellness, healthcare, and pharma) could be further explored to understand if emoji effects are universal. The product type (hedonic or utilitarian) may be a moderator, as found in the work of

Das et al. (

2019) and

Mladenović et al. (

2022).

5.2.2. Marketing Channels and Underrepresentation of Advertising

The observed effects of emojis can be studied in more marketing channels and platforms with a more holistic approach. Results from studies located in an organic social media context should be examined in other settings, such as social media advertisements, email marketing, and display ads. By systematically comparing emojis across channels and platforms, we will be able to uncover moderators and mediators of the relationships. At a practical level, marketers will be able to tailor their strategies and make a more efficient use of emojis.

The absence of advertising research is also a critical gap that must be addressed. Exploring whether results from organic social media content are reproduced in advertising will be practically beneficial, and it will also shed light on our previous theoretical suggestion that EASI is the right theoretical basis to explain emojis in marketing. The main reason is that, in advertising, message types can be drastically different than in organic content, in that the content is more persuasive and potentially assertive. Emojis in advertising could potentially trigger psychological reactance of the users because they see the message with more skepticism than organic posts, which may be perceived as more authentic and informal.

Linking this point with the theoretical discussion and the emergence of EASI as an appropriate framework, the concept of perceived appropriateness under the EASI theory (

Van Kleef et al., 2011) and the concept of persuasion knowledge (

Friestad & Wright, 1994) could be relevant here. If reactance happens because of the awareness of the ad, it could affect both the inferential and the affective pathways: the first because the emotion would seem fake and the second because of the negative reaction (

Evans & Park, 2015). This may be tested with designs exploring the same emoji characteristics in two settings: organic posts and social media advertising.

On the other hand, could emojis reduce psychological reactance in advertising? Taken together, our previous findings about the informal nature of emojis, their connection to brand Anthropomorphism, and the fact that they carry emotions and are more conversational because of their everyday use in messaging apps, show that they could actually reduce resistance to advertising by minimizing the sense that the message is corporate or assertive.

Customers are becoming more aware of covert advertising practices, and perceived covertness, intrusiveness, and manipulation have been linked with negative attitudes to the ad (

H. Kim et al., 2025). In this direction,

emojis could signal friendliness and authenticity, and they could mitigate the negative effect. Linking back to the EASI theory and perceived appropriateness, if emojis are perceived as a genuine attempt by the brand to communicate in a warm and friendly way, then they are beneficial. While there are no studies exploring this question, humor in advertising has been shown to reduce resistance under many conditions (

H. Kim et al., 2025).

Given the initial emphasis on Purchase-Related Outcomes, advertising would be the ideal channel to explore these dependent variables with ecological validity, as it relies on conversion metrics. We acknowledge the multitude of obstacles faced by researchers (budget, access to advertising accounts, and lack of consent to use business data) and we propose another route to overcome them. Researchers could create partnerships with advertisers or agencies to conduct A/B tests in real campaigns and to reveal if findings about emoji effectiveness translate to actual advertising performance.

5.2.3. Cross-Cultural Examination

Cross-cultural studies about emojis remain underexplored and can be addressed in the future. Given the analysis, at the moment,

we cannot assume universality or cultural specificity for emoji characteristics. Future research should systemize cross-cultural comparisons and address the significant geographic imbalances. A good start would be to address if and how cultural dimensions moderate the two pathways (inferential and affective) of the EASI theory. There is some evidence that East Asians and Western people are not influenced by faces in the same way (

Fang et al., 2021), and this could be validated for facial emojis, too.

Also, the individualism/collectivism of the culture could be of importance in emoji usage, so differences in emoji usage by brands and the perceptions of consumers may be noticed (

Togans et al., 2021).

Moreover, since ambiguity has emerged as a potential moderating factor, we posit that it may be tolerated differently in countries with high uncertainty avoidance; thus, it may be tested in countries with low versus high scores.

5.3. Characteristics

The analysis of the characteristics of the studies reveals several significant opportunities for future research schemes. We draw on the findings and the future directions in the

Appendix A,

Table A14.

First, there is a gap in understanding the antecedents of current emoji use by brands. Studies that will try to understand why some firms do not use emojis in their strategies could further advance the field, given that most experimental designs use emojis as an independent variable.

Second, future studies should move beyond the basic structures of Emoji-to-Engagement or Emoji-to-Purchase Intention and explore more complex approaches, firstly by including mediators that would give a deeper view on the observed results and secondly by measuring actual purchases instead of intentions. If the emojis have so much power to affect purchase intentions, then we need to go “back in the lab” and understand why by looking at variables across the funnel.

Third, more emoji attributes must be examined (as independent variables or as moderators) to understand under which circumstances the presence of emojis or number of emojis have specific effects. The semantic congruence of emojis with the text may be very important. In this direction, we may need to apply cross-cultural designs, as some emojis probably carry different meanings in different cultures.

Fourth, something equally important is to see if and how the surrounding text, platform features, and audience characteristics play a role in emoji effectiveness and how they interact with other elements (e.g., the photo of the post or the advertisement).

Fifth,

time-related variables, such as frequency over time (repeated exposure) or the time of day,

may also be incorporated in experimental designs to uncover whether the effects are sustained. We have mentioned that the focus is on short-term results, but actually, this is implied by the choice of dependent variables, as time has not been discussed at all as a variable. Our suggestion is based on previous research about differences in arousal and valence at various times of the day (

English & Carstensen, 2014), diminishing results of persuasion attempts over time (

Vardikou et al., 2025a), and the effects of repetition (

Schmidt & Eisend, 2015).

Sixth, we would expect to see more studies examining the congruence of the emoji with brand traits, as less emphasis has been given on the relationship of emojis with attitudes about the brand (as a dependent variable) and brand characteristics (as independent variables).

Seventh, emoji frequency in content (how many emojis are present/tested) and combinations should be reported better in the next studies, as it may affect results, and, ideally, it should be tested to understand more about the optimal use of emojis in the text.

Eighth, since “position might be an important factor in emoji processing” (

Tang et al., 2024, p. 8), the choice of

placement of emojis must be carefully established and reported, as so far it seems that processing fluency but not comprehension is hurt by the substitution of words with emojis (

Orazi et al., 2023;

Scheffler et al., 2022).

Ninth, it would be crucial

to test the effects of emojis in settings where negative sentiment is conveyed, for example, in urgency/scarcity messages, cause-related content, or sustainability messaging. Until now, we observe a positivity bias, while emojis with a negative sentiment are widely used (

Pınarbaşı & Kırçova, 2021;

Casado-Molina et al., 2022;

Unicode Consortium, n.d.), Before that, though, we need more robust evidence on the question of whether brands follow the same patterns of emoji usage as users.

Tenth,

a wider spectrum of research using object and symbol emojis or comparing facial emojis with the other types is necessary. The interplay between the emoji type (face, object, and symbol) and the semantic and emotional congruence of the emojis may also be of importance, since both face and non-face emojis carry meaning and emotions. Initial evidence suggests that the use of the same “common” emojis may not be beneficial to brands, as they are “uninteresting” (

Guo & Wang, 2024).

5.4. Methodology

According to our methodological analysis, future emoji marketing research needs to follow multiple essential directions, which will improve both theoretical knowledge and practical implementation.

There is a current focus on online and lab experiments, on manual content analysis and on mixed methods, which shows that the field is emerging. In addition, we only explore what is working in the short-term and how firms use emojis to increase engagement.

Therefore, the field could progress to a stage where (1) we study how emojis interact with different contexts and consumer characteristics; (2) longitudinal research is employed to study effects over time; (3) field experiments need to become the primary research method for evaluating emoji effectiveness with ecological validity; (4) qualitative emoji perception studies will guide subsequent quantitative assessments; (5) the development of automated content analysis tools together with standardized taxonomies could enhance manual coding methods; (6) neurophysiological tools in neuromarketing studies are used to test emoji effects that cannot be observed in other ways, variables that precede engagement, and the informational and emotional processing of emojis; and (7) sampling must have diverse demographics and cultures to represent the global and multigenerational nature of emoji communication.

The implementation of these methodological improvements will advance emoji marketing research from its present state of infancy into a strong theoretical framework with practical applications.

6. Theoretical Contribution

This domain-based systematic literature review makes several theoretical contributions towards understanding emojis in a marketing context. With a T-C-C-M approach, we analyzed the current state of the field and the research gaps that may be addressed by future studies.

The analysis of explicit and implicit theories shows that (1) emojis in marketing are mostly researched with grounding in psychological theories, (2) there is a large body of studies that are atheoretical, and (3) many diverse theories are used.

All the above show that we need more theory-driven research that will be based on the mentioned theories and a robust theoretical framework to explain what kind of relationship the emojis have with consumer behavior variables as outcomes and under which circumstances.

This is the first systematic review to uncover implicit theories in emoji research. We revealed seven theories that were subtly used as the foundation, and these included Anthropomorphism, Communication Accommodation Theory, and emotional contagion. With this implicit concept analysis, we also found that emotional contagion is the most commonly used theory, together with EASI, and this result further means that the analysis of implicit theoretical concepts should be included in systematic literature reviews, as it may completely alter the landscape.

Our Implicit Theory analysis identified ambiguity as an important concept in emoji research that should be incorporated in future designs. The definition and measurement of emoji ambiguity are critical steps in this direction.

Under the TCCM framework, we uniquely identified other characteristics of emojis, and we suggest that a more robust theoretical framework is created—one that unifies all the properties of emojis, such as semantic, emotional, symbolic, and decorative. The EASI theory could cover the semantic and emotional properties, but there was only one attempt to extend it to emojis (

Erle et al., 2022), which only confirmed that, for emojis, the affective pathway works in the same manner.

7. Managerial Implications

Emojis have been examined for their power to influence user engagement and purchase intentions, and marketers may find rich information on settings under which emojis are effective to drive immediate outcomes as well as repurchase intentions.