Intergroup Meta-Respect Perceptions in a Context of Conflict

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Respect

1.2. Intergroup Respect

1.3. Intergroup Meta-Perceptions

1.4. The Accuracy or Inaccuracy of Meta-Perceptions

1.5. The Present Research

- Jewish and Arab participants will inaccurately perceive their respective outgroups as significantly less respectful toward them than the outgroups actually report, reflecting an outgroup-negativity bias in meta-perceptions.

- Higher levels of respect toward the outgroup, as well as higher levels of perceived outgroup respect (meta-respect), will be positively associated with perceiving the outgroup as human.

- Presenting participants with information that directly challenges misperceptions—specifically, evidence that the outgroup expresses higher levels of respect than assumed—will foster more positive intergroup attitudes. These improvements are expected to manifest in heightened positive feelings and perceptions toward the outgroup, greater acknowledgment of its worthiness of respect, and stronger willingness for intergroup contact.

- Presenting evidence of outgroup respect without explicitly correcting misperceptions will also promote positive attitudes, although the magnitude of its effect relative to the corrective intervention remains an open empirical question.

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Outgroup Deservedness of Respect

2.2.2. Meta-Respect Toward the Outgroup

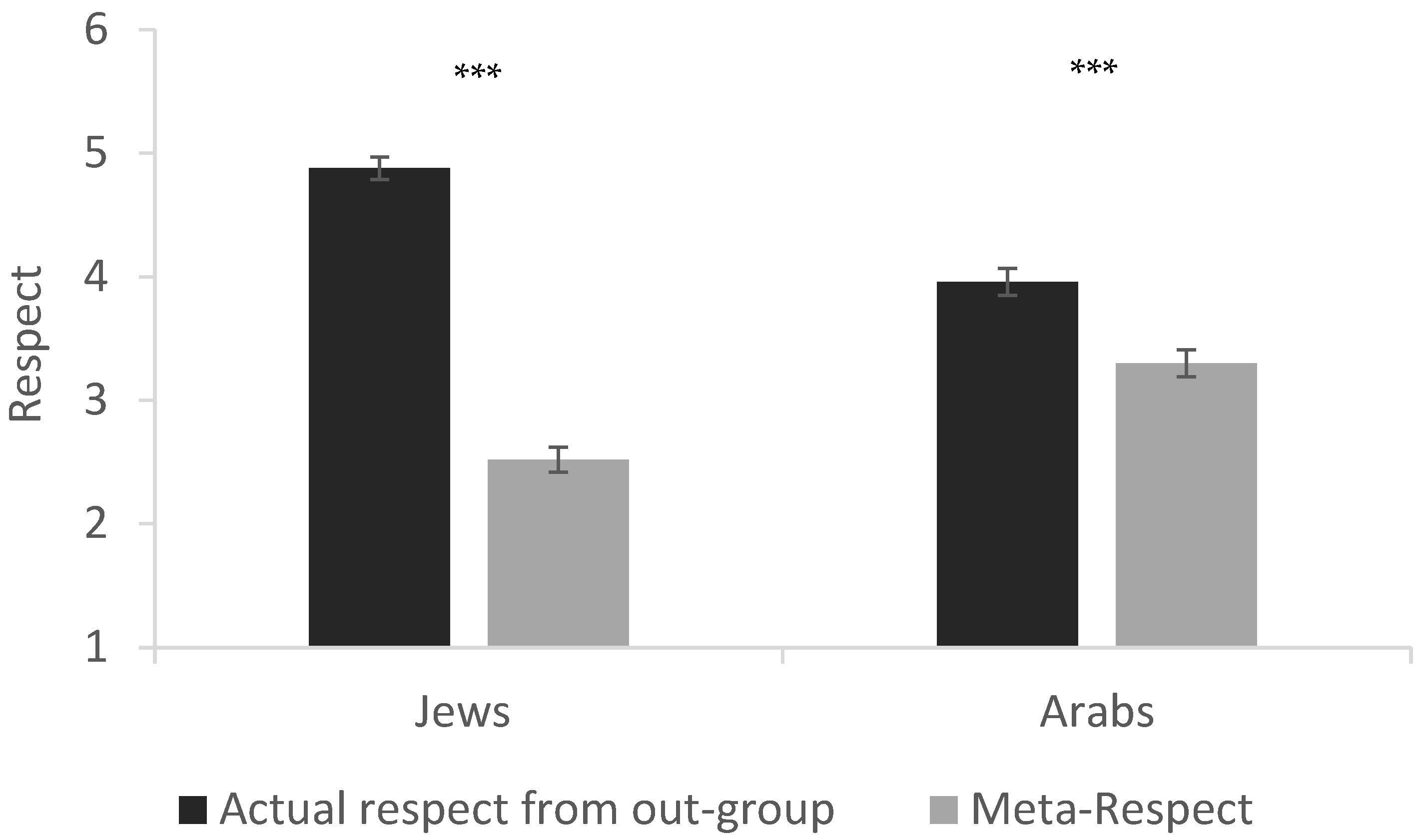

2.2.3. Accuracy/Inaccuracy of Meta-Respect

2.2.4. Correlations Among Outgroup Deservedness of Respect, Meta-Respect, and Outgroup Humanization

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Procedure

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Meta-Respect Toward the Outgroup

3.2.2. The Effect of Outgroup Respect and Meta-Respect Correction on Intergroup Attitudes

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acar, B., Van Assche, J., Velarde, S. A., Gonzalez, R., Lay, S., Rao, S., & McKeown, S. (2024). RESPECT, find out what it means to mixing: Testing novel emotional mediators of intergroup contact effects. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 103, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Haim, E., & Semyonov, M. (2015). Ethnic stratification in Israel. In R. Sáenz, D. G. Embrick, & N. P. Rodríguez (Eds.), The international handbook of the demography of race and ethnicity (pp. 323–337). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D. (1998). Societal beliefs in times of intractable conflict: The Israeli case. International Journal of Conflict Management, 9(1), 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D. (2007). Sociopsychological foundations of intractable conflicts. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(11), 1430–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D. (2013). Intractable conflicts: Socio-psychological foundations and dynamics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, D., & Hameiri, B. (2020). Interventions to change well-anchored attitudes in the context of intergroup conflict. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(7), e12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D., & Hammack, P. L. (2012). Conflict, delegitimization, and violence. In L. R. Tropp (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict (pp. 29–52). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, B., Charlton, K., Dorr, N., & Hume, D. L. (2001). Status differences and in-group bias: A meta-analytic examination of the effects of status stability, status legitimacy, and group permeability. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borinca, I., Tropp, L. R., & Ofosu, N. (2021). Meta-humanization enhances positive reactions to prosocial cross-group interaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(3), 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borinca, I., Van Assche, J., & Koc, Y. (2024). How meta-humanization leads to conciliatory attitudes but not intergroup negotiation: The mediating roles of attribution of secondary emotions and blatant dehumanization. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 7, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Chen, S., Crisp, R. J., & Halperin, E. (2015). Perceptions of a changing world induce hope and promote peace in intractable conflicts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(4), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J., & Fazio, R. H. (1984). A new look at dissonance theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 17, 229–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, M., Elran, M., Wattad, M. S., Lavie, E., & Shafran Gittleman, I. (2023, December). Findings of a survey on Jewish-Arab relations—November 2023. The Institute for National Security Studies (INNS). Available online: https://www.inss.org.il/publication/spotlight-arab-jews/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., John, M. S., Halabi, S., Saguy, T., Pearson, A. R., & Riek, B. M. (2008). Majority and minority perspectives in intergroup relations: The role of contact, group representations, threat, and trust in intergroup conflict and reconciliation. In A. Nadler, T. E. Malloy, & J. D. Fisher (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup reconciliation (pp. 227–254). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N., Doosje, B., & Spears, R. (2004). Sources of respect: The effects of being liked by ingroups and outgroups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34(2), 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschert, S., & Simon, B. (2019). Respect and political disagreement: Can intergroup respect reduce the biased evaluation of outgroup arguments? PLoS ONE, 14(3), e0211556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finchilescu, G. (2010). Intergroup anxiety in interracial interaction: The role of prejudice and metastereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 66(2), 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S. T., & Dépret, E. (1996). Control, interdependence and power: Understanding social cognition in its social context. European Review of Social Psychology, 7(1), 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, F. E., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). Being seen as individuals versus as group members: Extending research on metaperception to intergroup contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, E. (2008). Group-based hatred in intractable conflict in Israel. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(5), 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kteily, N., Hodson, G., & Bruneau, E. (2016). They see us as less than human: Metadehumanization predicts intergroup conflict via reciprocal dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(3), 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J., & Cikara, M. (2020). Inaccurate group meta-perceptions drive negative out-group attributions in competitive contexts. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(3), 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lount, R. B., Jr., & Pettit, N. C. (2012). The social context of trust: The role of status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M., Porat, R., Yarkoney, A., Reifen Tagar, M., Kimel, S., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. (2017). Intergroup emotional similarity reduces dehumanization and promotes conciliatory attitudes in prolonged conflict. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(1), 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A. (2017). Dealing with dissonance: A review of cognitive dissonance reduction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(12), e12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Berg, S. L. (2024). The power of correcting meta-perceptions for improving intergroup relationships. In E. Halperin, B. Hameiri, & R. Littman (Eds.), Psychological intergroup interventions (pp. 136–148). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore-Berg, S. L., Ankori-Karlinsky, L. O., Hameiri, B., & Bruneau, E. (2020). Exaggerated meta-perceptions predict intergroup hostility between American political partisans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(26), 14864–14872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Berg, S. L., & Hameiri, B. (2024). Improving intergroup relations with meta-perception correction interventions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 28(3), 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasie, M. (2016). The role of respect and disrespect in conflicts: The case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict [Doctoral thesis, Tel Aviv University]. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Nasie, M. (2023a). Perceived respect from the adversary group can improve intergroup attitudes in a context of intractable conflict. British Journal of Social Psychology, 62(2), 1114–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasie, M. (2023b). The respect pyramid: A model of respect based on lay knowledge in two cultures. Culture & Psychology, 29(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, Y., Awida, M., & Hasson, Y. (2023, November). Trends in Jewish and Arab relations in Israel following the iron swords war. Research report of achord. Available online: https://www.achord.org.il/_files/ugd/e9f8ab_cdfd146352f24e5bb2d02f3b8f771a64.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Navarro-Carrillo, G., Valor-Segura, I., & Moya, M. (2018). Do you trust strangers, close acquaintances, and members of your ingroup? Differences in trust based on social class in Spain. Social Indicators Research, 135(2), 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nir, N., Nassir, Y., Hasson, Y., & Halperin, E. (2023). Kill or be killed: Can correcting misperceptions of out-group hostility de-escalate a violent inter-group out-break? European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(5), 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, Y. (2023). Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. In P. R. Kumaraswamy (Ed.), The Palgrave international handbook of Israel (pp. 1–12). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Saguy, T., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2008). Beyond contact: Intergroup contact in the context of power relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(3), 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnabel, N., & Nadler, A. (2008). A needs-based model of reconciliation: Satisfying the differential emotional needs of victim and perpetrator as a key to promoting reconciliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B., & Grabow, H. (2014). To be respected and to respect: The challenge of mutual respect in intergroup relations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B., Mommert, A., & Renger, D. (2015). Reaching across group boundaries: Respect from outgroup members facilitates recategorization as a common group. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(4), 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B., & Schaefer, C. D. (2018). Muslims’ tolerance towards outgroups: Longitudinal evidence for the role of respect. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(1), 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, S., Di Bernardo, G. A., Vezzali, L., Pendleton, S., & Tropp, L. R. (2020). Do they want contact with us? The role of intergroup contact meta-perceptions on positive contact and attitudes. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 30(5), 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3), 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 23–45). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Stith, R. (2004). The priority of respect: How our common humanity can ground our individual dignity. International Philosophical Quarterly, 44(2), 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp, L. R., & Pettigrew, T. F. (2005). Relationships between intergroup contact and prejudice among minority and majority status groups. Psychological Science, 16(12), 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L. (2017). Valence matters: Positive meta-stereotypes and interethnic interactions. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157(2), 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voca, S., Graf, S., & Rupar, M. (2022). Victimhood beliefs are linked to willingness to engage in intergroup contact with a former adversary through empathy and trust. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 26(3), 696–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorauer, J. D., Hunter, A. J., Main, K. J., & Roy, S. A. (2000). Meta-stereotype activation: Evidence from indirect measures for specific evaluative concerns experienced by members of dominant groups in intergroup interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 690–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorauer, J. D., & Kumhyr, S. M. (2001). Is this about you or me? Self-versus other-directed judgments and feelings in response to intergroup interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(6), 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorauer, J. D., Main, K. J., & O’Connell, G. B. (1998). How do individuals expect to be viewed by members of lower status groups? Content and implications of meta-stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 917–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzerbyt, V. Y., Judd, C. M., & Muller, D. (2013). How do they see us? The vicissitudes of metaperception in intergroup relations. In S. Demoulin, J.-P. Leyens, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), Intergroup misunderstandings: Impact of divergent social realities (pp. 63–83). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

| Jewish Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Think That Arabs Deserve Respect | Perceived Respect from Arabs (Meta-Respect) | ||||

| Deserve/not deserve respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) | Deserve/not deserve respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) |

| Strongly deserve | 22.2 | 64.3 | Strongly deserve | 7.1 | 30.2 |

| Deserve | 28.2 | Deserve | 7.1 | ||

| Fairly deserve | 13.9 | Fairly deserve | 15.9 | ||

| Fairly not deserve | 9.9 | 35.7 | Fairly not deserve | 11.1 | 69.8 |

| Not deserve | 10.3 | Not deserve | 17.9 | ||

| Strongly not deserve | 15.5 | Strongly not deserve | 40.9 | ||

| Arab Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Think That Jews Deserve Respect | Perceived Respect from Jews (Meta-Respect) | ||||

| Deserve/not deserve respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) | Deserve/not deserve respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) |

| Strongly deserve | 41.2 | 83.9 | Strongly deserve | 11.6 | 46.2 |

| Deserve | 29.6 | Deserve | 13.1 | ||

| Fairly deserve | 13.1 | Fairly deserve | 21.6 | ||

| Fairly not deserve | 10.6 | 16.1 | Fairly not deserve | 16.6 | 53.8 |

| Not deserve | 3.0 | Not deserve | 21.6 | ||

| Strongly not deserve | 2.5 | Strongly not deserve | 15.6 | ||

| Measures | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Outgroup deserves respect | 3.96 | 1.75 | -- | |||

| 2. Meta-respect | 2.52 | 1.63 | 0.38 ** | -- | ||

| 3. Outgroup humanization | 4.80 | 3.22 | 0.79 ** | 0.51 ** | -- | |

| 4. Political orientation (+left) | 2.15 | 0.88 | 0.39 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.41 ** | -- |

| Measures | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Outgroup deserves respect | 4.88 | 1.27 | -- | ||

| 2. Meta-respect | 3.30 | 1.59 | 0.28 ** | -- | |

| 3. Outgroup humanization | 6.11 | 2.54 | 0.59 ** | 0.48 ** | -- |

| Jewish Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Respect from Arabs (Meta-Respect): % of Participants Who Believe Arabs View Jews as Deserving/Not Deserving of Respect | Perceived Respect from Arabs (Meta-Respect): % of Arabs Who Believe Jews Deserve Respect (Average) | ||

| Deserve/not deserved respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) | 29.52% |

| Strongly deserve | 1.8 | 20.6 | |

| Deserve | 5.5 | ||

| Fairly deserve | 13.3 | ||

| Fairly not deserve | 20.6 | 79.4 | |

| Not deserve | 23 | ||

| Strongly not deserve | 35.8 | ||

| Arab Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Respect from Jews (Meta-Respect): % of Participants Who Believe Arabs View Arabs as Deserving/Not Deserving of Respect | Perceived Respect from Jews (Meta-Respect): % of Jews Who Believe Arabs Deserve Respect (Average) | ||

| Deserve/not deserve respect | Frequency (percent) | Cumulative frequency (percent) | 46.14% |

| Strongly deserve | 9.3 | 47.8 | |

| Deserve | 12.4 | ||

| Fairly deserve | 26.1 | ||

| Fairly not deserve | 19.9 | 52.2 | |

| Not deserved | 19.9 | ||

| Strongly not deserve | 12.4 | ||

| DV | Control | Outgroup Respect | Meta-Respect Correction | F (2, 164) | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling respect | 1.67 (1.02) | 2.27 (1.36) | 2.38 (1.24) | 5.35 | <0.01 | 0.06 | * Exp1, ** Exp2 > Control |

| Hope | 1.59 (1.03) | 2.36 (1.40) | 2.43 (1.26) | 7.59 | <0.001 | 0.08 | ** Exp1, ** Exp2 > Control |

| Positive light | 1.93 (1.05) | 2.38 (1.11) | 2.38 (1.00) | 3.25 | 0.041 | 0.04 | † Exp1, † Exp2 > Control |

| Outgroup humanization | 4.57 (3.14) | 5.40 (2.94) | 4.68 (2.62) | 1.31 | 0.272 | 0.01 | -- |

| Willingness to respect | 3.12 (1.30) | 3.62 (1.19) | 3.23 (1.11) | 2.57 | 0.079 | 0.03 | -- |

| Willingness to interact | 3.07 (1.81) | 3.30 (1.89) | 2.98 (1.50) | 0.51 | 0.597 | 0.006 | -- |

| DV | Control | Outgroup Respect | Meta-Respect Correction | F (2, 160) | p | η2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling respect | 2.32 (1.35) | 3.47 (1.26) | 3.15 (1.43) | 10.40 | <0.001 | 0.11 | *** Exp1, ** Exp2 > Control |

| Hope | 2.40 (1.30) | 3.67 (1.10) | 3.36 (1.27) | 15.68 | <0.001 | 0.16 | *** Exp1, *** Exp2 > Control |

| Positive light | 3.02 (1.12) | 3.68 (.94) | 3.52 (.93) | 6.19 | <0.01 | 0.07 | ** Exp1, * Exp2 > Control |

| Outgroup humanization | 6.23 (2.58) | 7.33 (2.19) | 6.42 (2.24) | 3.41 | 0.035 | 0.04 | * Exp1 > Control |

| Willingness to respect | 3.96 (1.04) | 4.24 (.82) | 4.08 (.87) | 1.27 | 0.284 | 0.01 | -- |

| Willingness to interact | 5.48 (1.52) | 5.92 (1.30) | 5.57 (1.41) | 1.44 | 0.240 | 0.02 | -- |

| Condition | Dependent Variable | b XM | b MY | Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outgroup respect vs. Control (n = 109) | Outgroup humanization | −0.30 ** | 0.68 ** | b = −0.21, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = −0.40 to −0.03 |

| TE: b = −0.47, SE = 0.26, 95% CI = −1.00 to 0.06 | ||||

| Willingness to respect the outgroup | −0.30 ** | 0.31 *** | b = −0.09, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = −0.17 to −0.02 | |

| TE: b = −0.27, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = −0.48 to −0.06 | ||||

| Willingness to interact with the outgroup | −0.30 ** | 0.47 *** | b = −0.14, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = −0.27 to −0.02 | |

| TE: b = −0.16, SE = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.46 to 0.13 | ||||

| Meta-respect correction vs. Control (n = 110) | Outgroup humanization | −0.71 ** | 0.63 ** | b = −0.44, SE = 0.19, 95% CI = −0.82 to −0.07 |

| TE: b = −0.20, SE = 0.51, 95% CI = −1.22 to 0.80 | ||||

| Willingness to respect the outgroup | −0.71 ** | 0.27 ** | b = −0.19, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = −0.35 to −0.03 | |

| TE: b = −0.15, SE = 0.20, 95% CI = −0.56 to 0.25 | ||||

| Willingness to interact with the outgroup | −0.71 ** | 0.29 * | b = −0.20, SE = 0.12, 95% CI = −0.43 to 0.03 | |

| TE: b = 0.01, SE = 0.27, 95% CI = −0.53 to 0.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nasie, M. Intergroup Meta-Respect Perceptions in a Context of Conflict. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111474

Nasie M. Intergroup Meta-Respect Perceptions in a Context of Conflict. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111474

Chicago/Turabian StyleNasie, Meytal. 2025. "Intergroup Meta-Respect Perceptions in a Context of Conflict" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111474

APA StyleNasie, M. (2025). Intergroup Meta-Respect Perceptions in a Context of Conflict. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111474