Gratitude Heals: State Gratitude Weakens the Objectification-Social Pain Link

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectification and Its Impact

1.2. Objectification and Social Pain

1.3. The Buffering Effect of Gratitude

1.4. Overview of Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Procedure and Measures

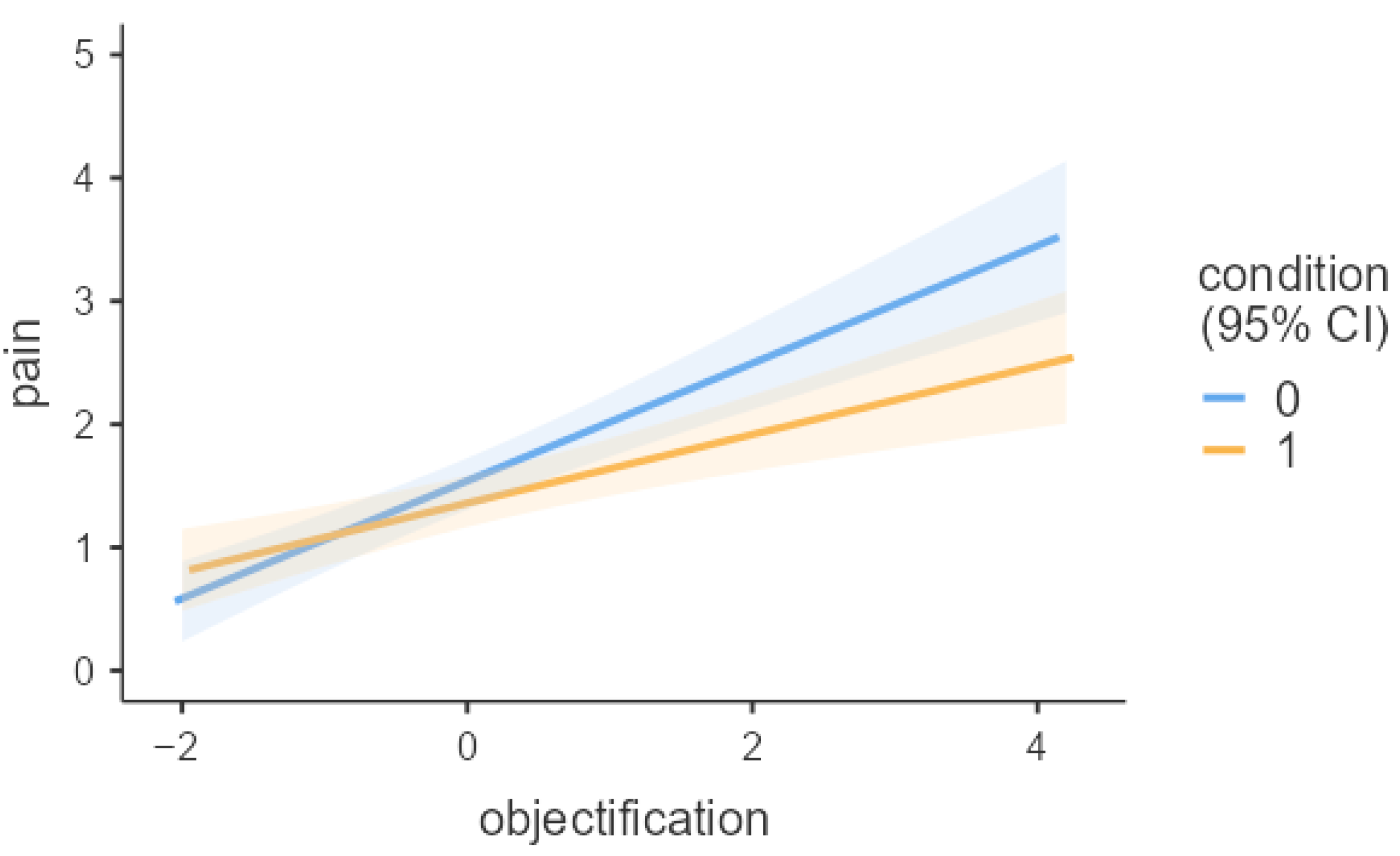

2.2. Results and Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Procedures and Measurements

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Materials and Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Procedures and Measurements

Suppose that you are currently working in a business. While interacting with your colleagues, they treat you like an object. They regard you as an instrument to fulfill a particular purpose.

Please imagine a scenario like this and describe it in writing.

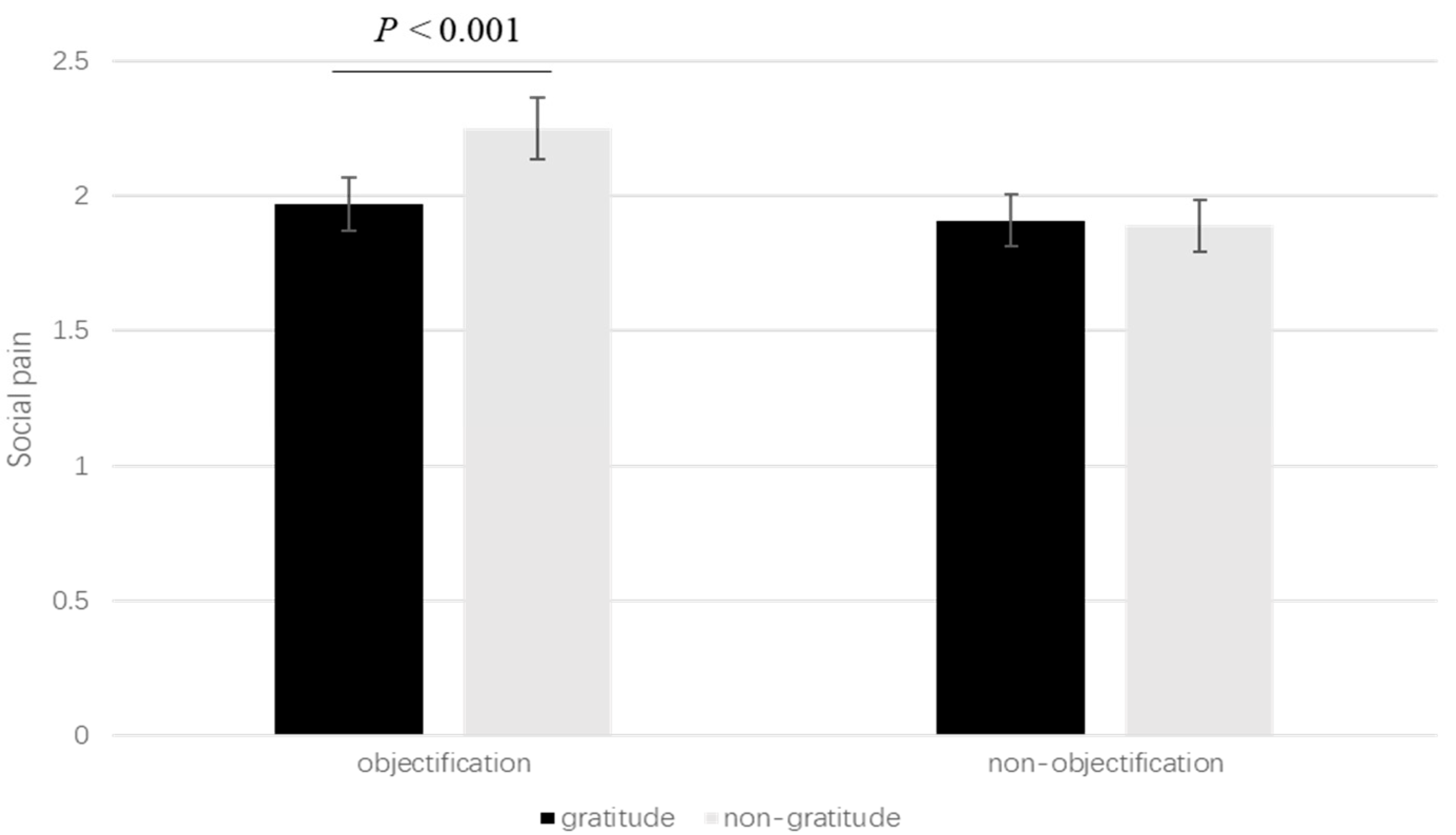

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. General Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkozei, A., Smith, R., & Killgore, W. D. S. (2018). Gratitude and subjective well-being: A proposal of two causal frameworks. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1519–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., & Volpato, C. (2017). (Still) Modern Times: Objectification at work. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., & Volpato, C. (2014). When work does not ennoble man: Psychological consequences of working objectification. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 21(3), 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., & Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: Anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmi, P., & Schroeder, J. (2020). Human “resources”? Objectification at work. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, D., Reeve, R. A., Champion, G. D., Addicoat, L., & Ziegler, J. B. (1990). The faces pain scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: Development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain, 41(2), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, E., Jacoby, N., Kteily, N., & Saxe, R. (2018). Denying humanity: The distinct neural correlates of blatant dehumanization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(7), 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, C., Eggleston, A., Brennan, R., & Over, H. (2025). To what extent is research on infrahumanization confounded by intergroup preference? Royal Society Open Science, 12(4), 241348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Williams, K. D. (2012). Imagined future social pain hurts more now than imagined future physical pain. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(3), 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Williams, K. D., Fitness, J., & Newton, N. C. (2008). When hurt will not heal: Exploring the capacity to relive social and physical pain. Psychological Science, 19(8), 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., Li, Z., Hao, M., Zhu, X., & Wang, F. (2022). Objectification limits authenticity: Exploring the relations between objectification, perceived authenticity, and subjective well-being. British Journal of Social Psychology, 61(2), 622–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converse, B. A., & Fishbach, A. (2012). Instrumentality boosts appreciation: Helpers are more appreciated while they are useful. Psychological Science, 23(6), 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudney, A., Whartman, L., O’Farrell, S., Tompkins, S., Cook, T., Graef, G., & Deichert, N. T. (2024). Perceived stress mediates the relationship between gratitude and pain-related outcomes. The Journal of Pain, 25(4), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Jiang, T., Gaer, W., & Poon, T. (2023). Workplace objectification leads to self-harm: The mediating effect of depressive moods. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(7), 1219–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichert, N. T., Fekete, E. M., & Craven, M. (2021). Gratitude enhances the beneficial effects of social support on psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(2), 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C. N., Lambert, N. M., Pond, R. S., Kashdan, T. B., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). A grateful heart is a nonviolent heart: Cross-sectional, experience sampling, longitudinal, and experimental evidence. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, M., Kelly, J. R., Tyler, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2021). I’m up here! Sexual objectification leads to feeling ostracized. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, A. (2000). Against the male flood: Censorship, pornography, and equality. In D. Cornell (Ed.), Oxford readings in feminism: Feminism and pornography (p. 30). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The pain of social disconnection: Examining the shared neural underpinnings of physical and social pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(6), 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R. A., McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J.-A. (2003). The assessment of gratitude. In S. J. Lopez, & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 327–341). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, R. B., Loeser, J. D., Baron, R., & Edwards, R. R. (2016). Assessment of chronic pain: Domains, methods, and mechanisms. The Journal of Pain, 17(9), T10–T20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., Finkel, E. J., & vanDellen, M. R. (2015). Transactive goal dynamics. Psychological Review, 122(4), 648–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimons, G. M., & Fishbach, A. (2010). Shifting closeness: Interpersonal effects of personal goal progress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, A. W., Wood, A. M., & Hyland, M. E. (2010). Attrition from self-directed interventions: Investigating the relationship between psychological predictors, intervention content and dropout from a body dissatisfaction intervention. Social Science & Medicine, 71(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenfeld, D. H., Inesi, M. E., Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Power and the objectification of social targets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P. L., Allemand, M., & Roberts, B. W. (2013). Examining the pathways between gratitude and self-rated physical health across adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, E., Koval, P., Stratemeyer, M., Thomson, F., & Haslam, N. (2017). Sexual objectification in women’s daily lives: A smartphone ecological momentary assessment study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. C., & Johnson, D. M. (2017). Applying objectification theory to the relationship between sexual victimization and disordered eating. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(8), 1091–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudd, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2021). Social pain and the role of imagined social consequences: Why personal adverse experiences elicit social pain, with or without explicit relational devaluation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 95, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K. S., Hettema, J. M., Butera, F., Gardner, C. O., & Prescott, C. A. (2003). Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 60(8), 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Ding, K., & Zhao, J. (2015). The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. C., & Yeh, Y. (2014). How gratitude influences well-being: A structural equation modeling approach. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S., Baldissarri, C., Spaccatini, F., & Elder, L. (2017). Internalizing objectification: Objectified individuals see themselves as less warm, competent, moral, and human. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., Murnane, T., Vaes, J., Reynolds, C., & Suitner, C. (2010). Objectification leads to depersonalization: The denial of mind and moral concern to objectified others. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(5), 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manela, T. (2022). Gratitude and meaning in life. In The Oxford handbook of meaning in life (pp. 401–415). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, D. M., & Slovic, P. (2020). Social, psychological, and demographic characteristics of dehumanization toward immigrants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(17), 9260–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J.-A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mee, S., Bunney, B. G., Bunney, W. E., Hetrick, W., Potkin, S. G., & Reist, C. (2011). Assessment of psychological pain in major depressive episodes. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(11), 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, K. L., Goldenberg, J., & Boyd, P. (2018). Women as animals, women as objects: Evidence for two forms of objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(9), 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., & Roch, S. (2007). Upstream reciprocity and the evolution of gratitude. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274(1610), 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermann, M. L. (2011). Moral disengagement in self-reported and peer-nominated school bullying. Aggressive behavior, 37(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, M. K., Igou, E. R., & van Tilburg, W. A. (2024). Preventing boredom with gratitude: The role of meaning in life. Motivation and Emotion, 48(1), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orehek, E., & Forest, A. L. (2016). When people serve as means to goals: Implications of a motivational account of close relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(2), 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orehek, E., & Weaverling, C. G. (2017). On the nature of objectification: Implications of considering people as means to goals. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Over, H. (2021). Seven challenges for the dehumanization hypothesis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.-T., Chen, Z., Teng, F., & Wong, W.-Y. (2020). The effect of objectification on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 87, 103940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., & Chen, Z. (2024). When humility heals: State humility weakens the relationship between objectification and aggression. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 20(2), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., Wang, X., Teng, F., & Chen, Z. (2023). A little appreciation goes a long way: Gratitude reduces objectification. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(4), 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statman, D. (2024). Rejecting the objectification hypothesis. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 15(1), 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review, 9(3), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J., Baumeister, R., Tice, D., & Stucke, T. (2001). If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaes, J., Paladino, M. P., & Haslam, N. (2021). Seven clarifications on the psychology of dehumanization. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelisti, A., Young, S., Carpenter-Theune, K., & Alexander, A. (2005). Why does it hurt?: The perceived causes of hurt feelings. Communication Research, 32(4), 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 31(5), 431–451. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D., & Naragon-Gainey, K. (2010). On the specificity of positive emotional dysfunction in psychopathology: Evidence from the mood and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/schizotypy. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 275–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(9), 1076–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009). Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the big five facets. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(4), 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Cai, Q., Shen, B., Gao, X., & Zhou, X. (2017). Neural substrates and social consequences of interpersonal gratitude: Intention matters. Emotion, 17(4), 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B., Wisse, B., & Lord, R. G. (2025). Workplace objectification: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 35(4), 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, Z. Gratitude Heals: State Gratitude Weakens the Objectification-Social Pain Link. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111452

Qiu J, Shi J, Chen Z. Gratitude Heals: State Gratitude Weakens the Objectification-Social Pain Link. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111452

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Junjie, Jiaxin Shi, and Zhansheng Chen. 2025. "Gratitude Heals: State Gratitude Weakens the Objectification-Social Pain Link" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111452

APA StyleQiu, J., Shi, J., & Chen, Z. (2025). Gratitude Heals: State Gratitude Weakens the Objectification-Social Pain Link. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111452