Associations Between Social Media Use and Mental Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objective

2. Methodology

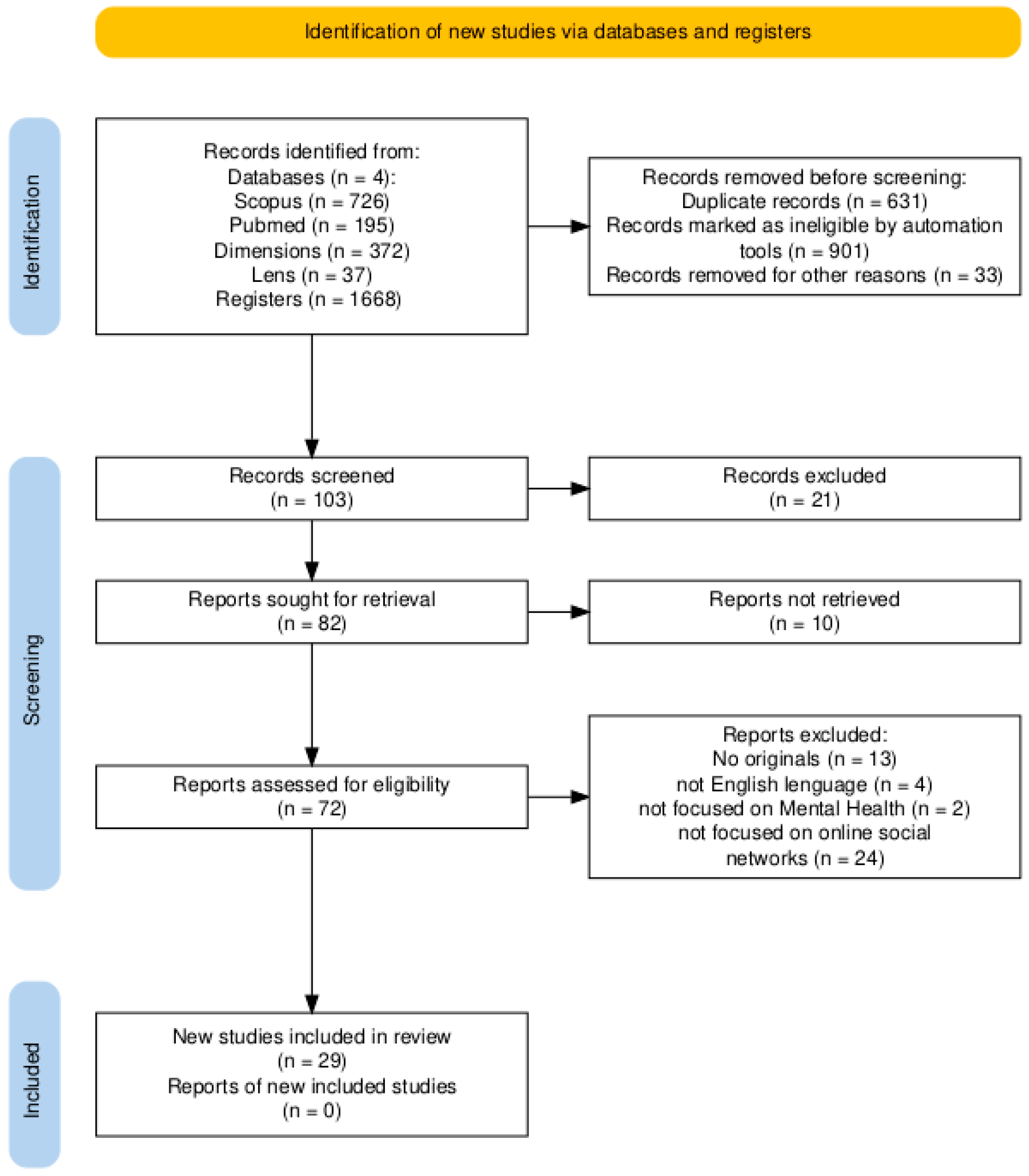

Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Synthesis

3.2. Internalizing Disorders

3.3. Externalizing Disorders

3.4. Emerging Patterns and Underlying Mechanisms

- Normalization of maladaptive behaviors via repeated exposure to violent or suicide-related content (Abrutyn et al., 2020; Rossi & DeSilva, 2020).

- Behavioral disinhibition facilitated by anonymity in interactions with strangers ((Craig et al., 2020): RR = 1.40 for cyberbullying in 28% of countries).

- Maladaptive stress management through substance use (Pravosud et al., 2024) or compulsive SNS use (Victor et al., 2024).

- Diffusion of aggressive or unrealistic models in digital communities, exacerbating negative social comparison and body dissatisfaction (de Felice et al., 2022; Farias et al., 2024).

- Disruption of sleep–wake cycles due to nocturnal use and hyperconnectivity, impacting mood and emotion regulation (Tajjamul & Aleem, 2022; Hamilton & Lee, 2021).

- AXIS (20 items; quantitative): Each item rated yes/no/partially; “yes” responses were tallied to determine compliance (Downes et al., 2016).

- CASPe (10 items; qualitative) (CASPe, 2020): Items scored 0–2; studies scoring ≥18 points (90%) were considered high quality.

- Tools were applied jointly alongside STROBE and ROBINS-I for exposure/transversal designs (von Elm et al., 2007; Vandenbroucke et al., 2014; Sterne et al., 2016).

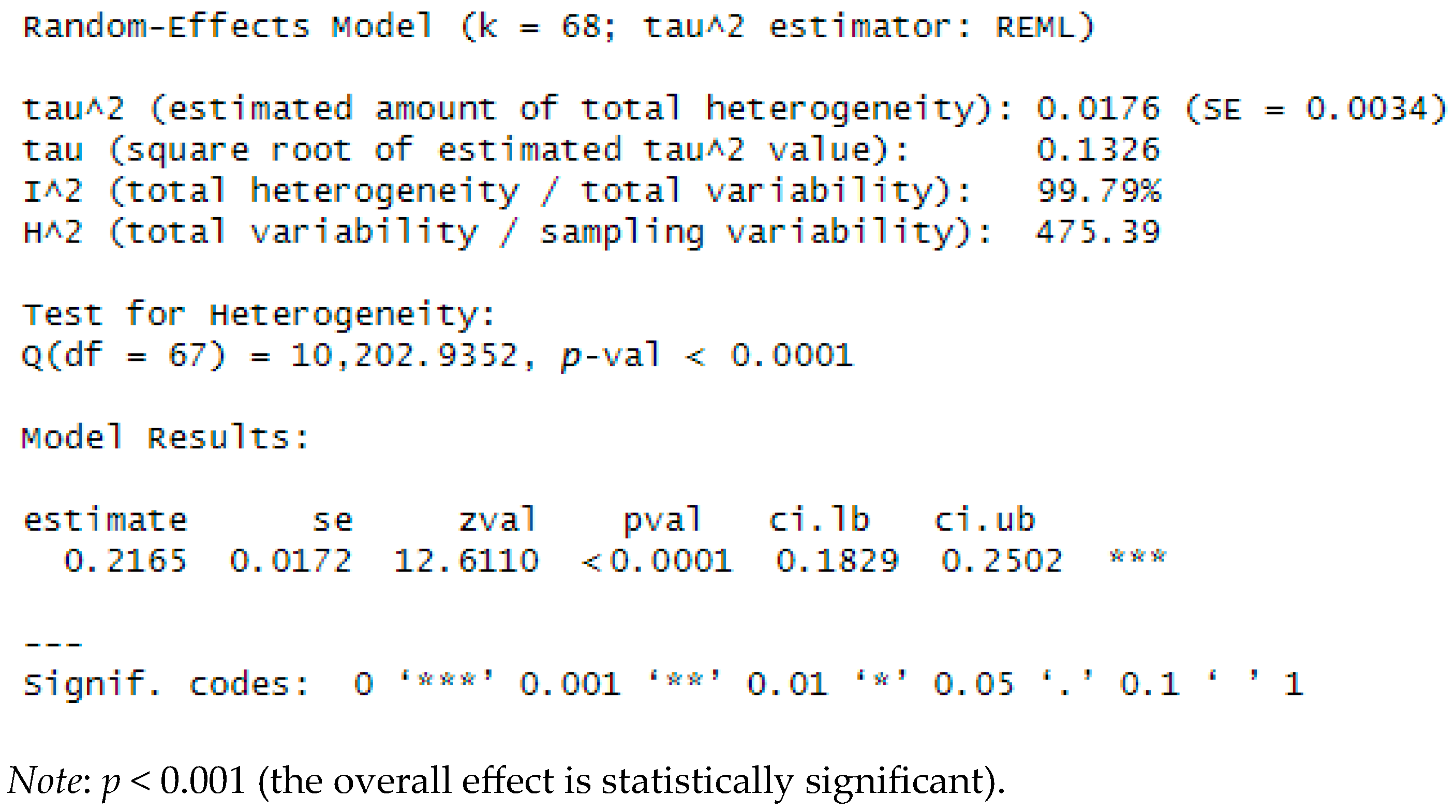

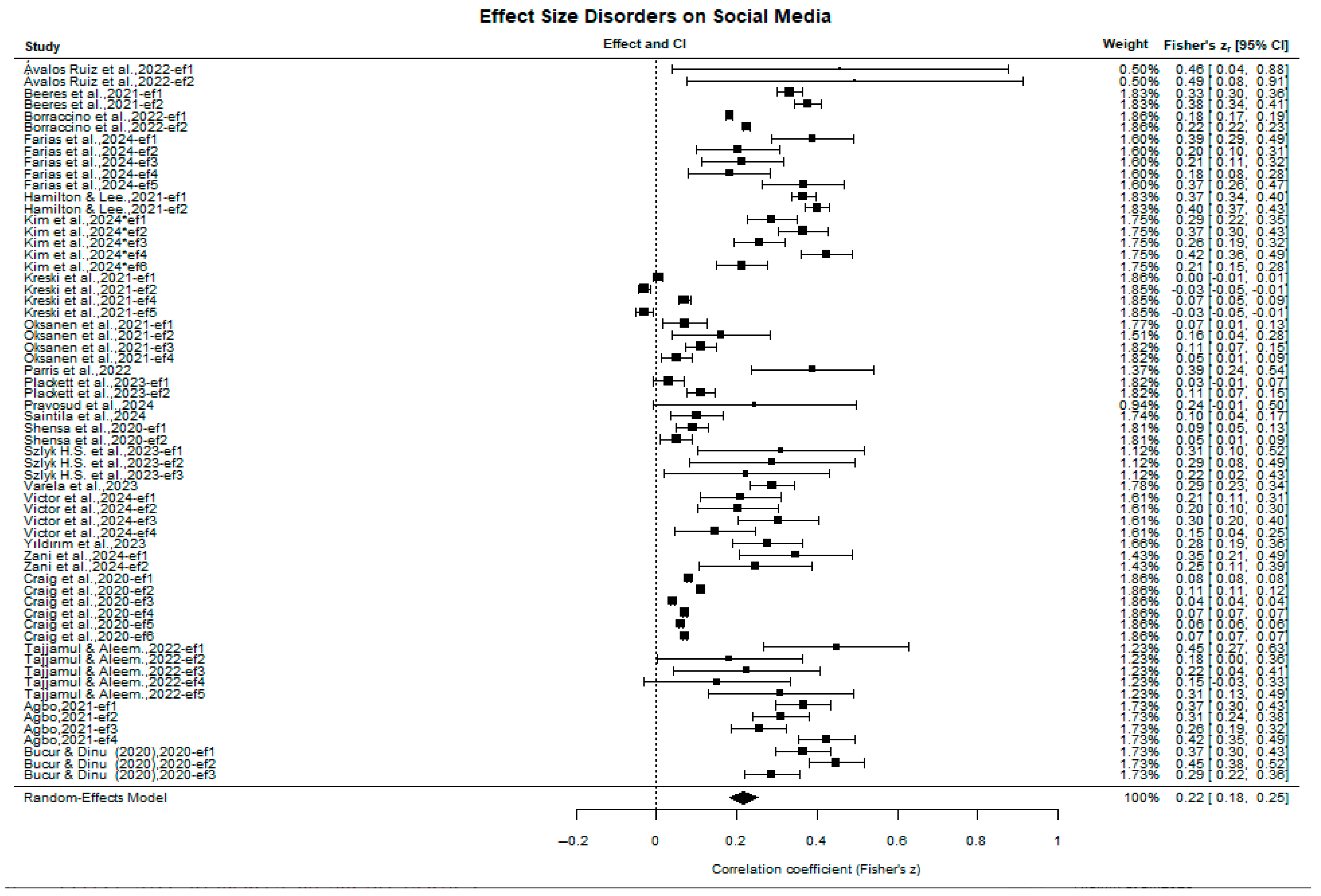

3.5. Meta-Analysis

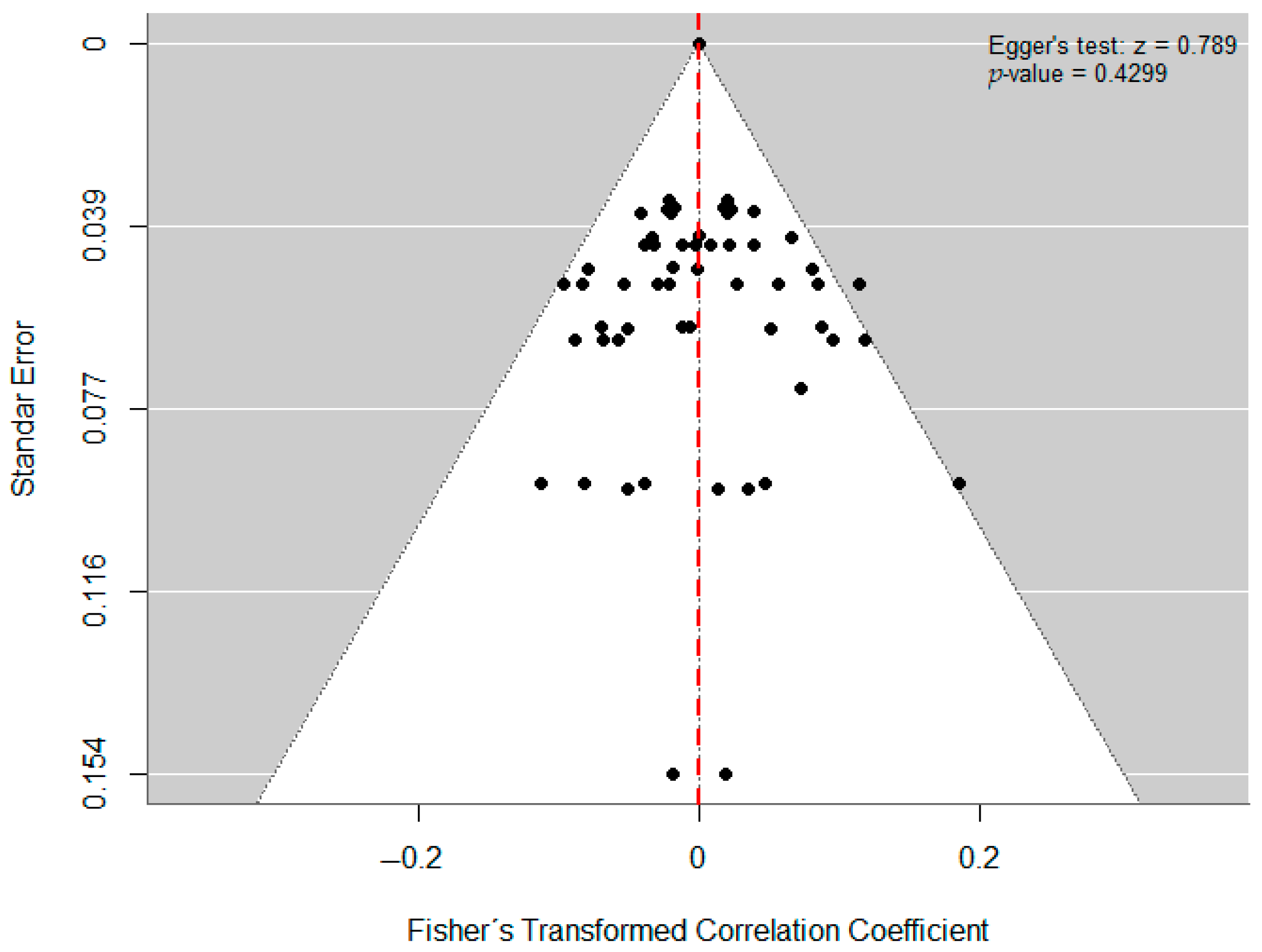

3.6. Publication Bias Risk Assessment

- H0: no publication bias (intercept = 0);

- H1: possible publication bias (intercept ≠ 0); reject H0 if p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

- Conduct longitudinal and intervention studies to establish causality and evaluate preventive strategies.

- Investigate the platform- and algorithm-specific roles in risk amplification.

- Examine protective factors (resilience, critical digital literacy, family/school support) across cultural contexts.

- Employ mixed-methods approaches to capture the complexity of subjective experience.

- Develop and enforce legal frameworks that protect minors’ privacy and well-being online (e.g., laws similar to those in Florida and Colombia).

- Require greater algorithmic transparency from SNS companies and effective mechanisms for removing content promoting self-harm, suicide, cyberbullying, or unrealistic body ideals.

- Integrate digital and mental health education into school curricula.

- Implement early screening programs for problematic SNS use and comorbidities in primary care and school settings.

- Develop psychoeducational interventions for adolescents and families that encourage critical, healthy SNS use, promote emotion regulation skills, and strengthen face-to-face interactions.

- Create and promote accessible crisis-support resources via digital channels for at-risk youth.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrutyn, S., Mueller, A. S., & Osborne, M. (2020). Rekeying cultural scripts for youth suicide: How social networks facilitate suicide diffusion and suicide clusters following exposure to suicide. Society and Mental Health, 10(2), 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, M. C. (2021). Social media use: A risk factor for depression among school adolescents in Enugu State of Nigeria. Children and Teenagers, 4(2), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., & Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interaction between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 56, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos Ruiz, I., Cuevas López, M., Lizarte Simón, E. J., & López Rodríguez, S. (2022). Use of ICT and social networks in the neurodevelopment of minors. Implications for the prevention of the risk of social exclusion. Texto Livre: Linguagem e Tecnologia, 15, e40508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balt, E., Mérelle, S., Robinson, J., Popma, A., Creemers, D., van den Brand, I., van Bergen, D., Rasing, S., Mulder, W., & Gillissen, R. (2023). Social media use of adolescents who died by suicide: Lessons from a psychological autopsy study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News World. (2024, March 25). Florida prohíbe a los menores de 14 años tener cuentas en redes sociales. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/c98r5rgz8jlo (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Beeres, D. T., Andersson, F., Vossen, H. G. M., & Galanti, M. R. (2021). Social media and mental health among early adolescents in Sweden: A longitudinal study with 2-year follow-up (KUPOL study). Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(6), 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borraccino, A., Marengo, N., Dalmasso, P., Marino, C., Ciardullo, S., Nardone, P., Lemma, P., & The 2018 HBSC-Italia Group. (2022). Problematic social media use and cyber aggression in Italian adolescents: The remarkable role of social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, A.-M., & Dinu, L. P. (2020). Detecting Early Onset of Depression from Social Media Text using Learned Confidence Scores. In Accademia University Press EBooks (pp. 73–78). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASPe. (2020). Critical appraisal skills programme español. Disponible en. Available online: https://redcaspe.org/materiales/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Conway, C. C., Forbes, M. K., Forbush, K. T., Fried, E. I., Hallquist, M. N., Kotov, R., Mullins-Sweatt, S. N., Shackman, A. J., Skodol, A. E., South, S. C., Sunderland, M., Waszczuk, M. A., Zald, D. H., Afzali, M. H., Bornovalova, M. A., Carragher, N., Docherty, A. R., Jonas, K. G., Krueger, R. F., … Eaton, N. R. (2019). A hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology can transform mental health research. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 14(3), 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (Eds.). (2019). Manual de Síntesis y Metaanálisis de Investigación. Fundación Russell Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., Elgar, F. J., Inchley, J., Janssen, I., Költo, A., Looze, M. D., Matos, M. G., Pickett, W., Currie, D. B., Malinowska-Cieślik, M., Pavlova, D., Godeau, E., Nic Gabhainn, S., Molcho, M., & Vieno, A. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felice, G., Burrai, J., Mari, E., Paloni, F., Lausi, G., Giannini, A. M., & Quaglieri, A. (2022). How do adolescents use social networks and what are their potential dangers? A qualitative study of gender differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. (2019). Scopus: Content coverage guide. Elsevier B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, M., Manieu, D., Baeza, E., Monsalves, C., Vera, N., Vergara-Barra, P., & Leonario-Rodríguez, M. (2024). Social networks and risk of eating disorders in Chilean young adults. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 41(2), 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, D. (2021). Social media and health care, part I: Literature review of social media use by health care providers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e23205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, D., Martinez-Menchaca, H. R., Ahmed, M., & Farsi, N. (2022). Social media and health care (part II): Narrative review of social media use by patients. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e30379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieiro, P., González-Rodríguez, R., & Domínguez-Alonso, J. (2022). Self-esteem and socialisation in social networks as determinants in adolescents’ eating disorders. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e4416–e4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. (2024). Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet (London, England), 403(10440), 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Torres, M. A. (2024). Technology at the rescue? Online games, adolescent mental health and the COVID pandemic. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 84(2), 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, G. S., Pedersen, B. N., & Sneppen, K. (2021). Social contagion in a world with asymmetric influence. Physical Review E, 103(2–1), 022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J. L., & Lee, W. (2021). Associations between social media, bedtime technology use rules, and daytime sleepiness among adolescents: Cross-sectional findings from a nationally representative sample. JMIR Mental Health, 8(9), e26273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M. H., Lee, J. J., & Yen, H. Y. (2023). Associations between older adults’ social media use behaviors and psychosocial well-being. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(10), 2247–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, M., Vidya, R., Kothari, A., & Gulluoglu, B. M. (2023). New media platforms for teaching and networking: Emerging global opportunities for breast surgeons. Breast Care (Basel, Switzerland), 18(3), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C., Buchweitz, C., Caye, A., Silvani, J., Ameis, S. H., Brunoni, A. R., Cost, K. T., Courtney, D. B., Georgiades, K., Merikangas, K. R., Henderson, J. L., Polanczyk, G. V., Rohde, L. A., Salum, G. A., & Szatmari, P. (2024). Worldwide prevalence and disability from mental disorders across childhood and adolescence: Evidence from the global burden of disease study. JAMA Psychiatry, 81(4), 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Jiang, T., Baek, J. H., Jang, S. H., & Zhu, Y. (2024). Understanding and comparing risk factors and subtypes in South Korean adult and adolescent women’s suicidal ideation or suicide attempt using survey and social media data. Digital Health, 10, 20552076241255660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., Brown, T. A., Carpenter, W. T., Caspi, A., Clark, L. A., Eaton, N. R., Forbes, M. K., Forbush, K. T., Goldberg, D., Hasin, D., Hyman, S. E., Ivanova, M. Y., Lynam, D. R., Markon, K., … Zimmerman, M. (2017). The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreski, N., Platt, J., Rutherford, C., Olfson, M., Odgers, C., Schulenberg, J., & Keyes, K. M. (2021). Social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador, M., Sánchez-Iglesias, I., Bernaldo-de-Quirós, M., Estupiñá, F. J., Fernandez-Arias, I., Vallejo-Achón, M., & Labrador, F. J. (2023). Video game playing and internet gaming disorder: A profile of young adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(24), 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibenluft, E., & Barch, D. M. (2021). Adolescent brain development and psychopathology: Introduction to the special issue. Biological Psychiatry, 89(2), 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L., & Chu, H. (2018). Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 74(3), 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, J. A., Marín-Martínez, F., Sánchez-Meca, J., Van den Noortgate, W., & Viechtbauer, W. (2014). Estimación del poder predictivo del modelo en metarregresión de efectos mixtos: Un estudio de simulación. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(1), 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, M. C., García-Rodriguez, I., Arias-Ramos, N., García-Fernández, R., Trevissón-Redondo, B., & Liébana-Presa, C. (2021). Cannabis use and emotional intelligence in adolescents during COVID-19 confinement: A social network analysis approach. Sustainability, 13(23), 12954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones de Colombia. (2024). Ministerio TIC respalda Proyecto de Ley para regular el uso de redes sociales en menores de 14 años. Ministerio TIC. Available online: https://mintic.gov.co/portal/inicio/Sala-de-prensa/Noticias/398907:Ministerio-TIC-respalda-Proyecto-de-Ley-para-regular-el-uso-de-redes-sociales-en-menores-de-14-anos (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Moro, Á., Ruiz-Narezo, M., & Fonseca, J. (2022). Use of social networks, video games and violent behaviour in adolescence among secondary school students in the Basque Country. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application (pp. 3–22). Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, S. A., Stormark, K. M., Heradstveit, O., & Breivik, K. (2023). Trends in physical health complaints among adolescents from 2014–2019: Considering screen time, social media use, and physical activity. SSM—Population Health, 22, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, A., Miller, B. L., Savolainen, I., Sirola, A., Demant, J., Kaakinen, M., & Zych, I. (2021). Social media and access to drugs online: A nationwide study in the United States and Spain among adolescents and young adults. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 13(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, L., Lannin, D. G., Hynes, K., & Yazedjian, A. (2022). Exploring social media rumination: Associations with bullying, cyberbullying, and distress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), NP3041–NP3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Pacheco, E. (2023). Going PubMed, Writing Together! Journal of the ASEAN Federation of Endocrine Societies, 38(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, R. (2020). Using the Lens Database for Staff Publications. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 108(2), 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plackett, R., Sheringham, J., & Dykxhoorn, J. (2023). The longitudinal impact of social media use on UK adolescents’ mental health: Longitudinal observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e43213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L. M., Iorga, M., & Iurcov, R. (2022). Body-esteem, self-esteem and loneliness among social media young users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pravosud, V., Ling, P. M., Halpern-Felsher, B., & Gribben, V. (2024). Social media exposure and other correlates of increased e-cigarette use among adolescents during remote schooling: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 7(1), e49779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.5.0) [Computer software]. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Rossi, G., & DeSilva, R. (2020). Social media applications: A potential avenue for broadcasting suicide attempts and self-injurious behavior. Cureus, 12(10), e10759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintila, J., Oblitas-Guerrero, S. M., Larrain-Tavara, G., Lizarraga-De-Maguiria, I. G., Bernal-Corrales, F. C., López-López, E., Calizaya-Milla, Y. E., Serpa-Barrientos, A., & Ramos-Vera, C. (2024). Associations between social network addiction, anxiety symptoms, and risk of metabolic syndrome in Peruvian adolescents—A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1261133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Switzer, G. E., Primack, B. A., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2020). Emotional support from social media and face-to-face relationships: Associations with depression risk among young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shunmugam, M., Chakrapani, V., Kumar, P., Mukherjee, D., & Madhivanan, P. (2023). Use of smartphones for social and sexual networking among transgender women in South India: Implications for developing smartphone-based online hiv prevention interventions. Indian Journal of Public Health, 67(4), 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2020). The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. arXiv, arXiv:2011.00223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sserunkuuma, J., Kaggwa, M. M., Muwanguzi, M., Najjuka, S. M., Murungi, N., Kajjimu, J., Mulungi, J., Kihumuro, R. B., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., & Ashaba, S. (2023). Problematic use of the internet, smartphones, and social media among medical students and relationship with depression: An exploratory study. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e0286424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A.-W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., … Ramsay, C. R. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlyk, H. S., Li, X., Kasson, E., Peoples, J. E., Montayne, M., Kaiser, N., & Cavazos-Rehg, P. (2023). How do teens with a history of suicidal behavior and self-harm interact with social media? Journal of Adolescence, 95(4), 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajjamul, S., & Aleem, N. (2022). Impacts of social media on mental health of youth in Karachi, Pakistan: An exploratory study. Global Digital & Print Media Review V(II), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremolada, M., Silingardi, L., & Taverna, L. (2022). Social networking in adolescents: Time, type and motives of using, social desirability, and communication choices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P. M., Meier, A., & Beyens, I. (2022). Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., Poole, C., Schlesselman, J. J., Egger, M., & STROBE Initiative. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. International Journal of Surgery, 12(12), 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, A., Simpson, E. G., Gagnon, S., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2020). Social media use and risky behaviors among adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, J. J., Pérez, J. C., Rodríguez-Rivas, M. E., Chuecas, M. J., & Romo, J. (2023). Wellbeing, social media addiction and coping strategies among Chilean adolescents during the pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1211431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, S. A., Ibrahim, M. S., Yusuf, S., Mahmud, N., Bahari, K. A., Ling, L. Y., & Mubin, N. N. A. (2024). Social media addiction and depression among adolescents in two Malaysian states. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2292055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W., & López-López, J. A. (2022). Location-scale models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(6), 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & the STROBE Initiative. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet, 370(9596), 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Li, Q., Lu, J., Ran, H., Che, Y., Fang, D., Liang, X., Sun, H., Chen, L., Peng, J., Shi, Y., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Treatment rates for mental disorders among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 6(10), e2338174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., Hu, Y., & Qi, H. (2022). Digital health literacy: Bibliometric analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(7), e35816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M., Öztürk, A., & Solmaz, F. (2023). Fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems in Turkish young adults: Mediating roles of happiness and problematic social networking sites use. Psihologija, 56(4), 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, B. N., Said, F. M., Nambiar, N., & Sholihat, S. (2024). The relationship between social media dependency, mental health, and academic performance among adolescents in Indonesia. International Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedicine (IJBB), 1(2), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“risk factors” OR “prevention”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Social Media” OR “Social Network*” OR “online social network*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“adolescents” OR “young adult”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| ((“risk factor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “prevention”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Mental Health”[Title/Abstract] OR “mental disorder*”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“social network*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Social Media”[Title/Abstract] OR “online social network*”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“adolescent*”[Title/Abstract] OR “young adult*”[Title/Abstract])) OR ((“Risk Factors”[MeSH Terms] OR “prevention and control”[MeSH Subheading]) AND (“Mental Health”[MeSH Terms] OR “Mental Disorders”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“Social Networking”[MeSH Terms] OR “Social Media”[MeSH Terms] OR “Online Social Networking”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“Adolescent”[MeSH Terms] OR “Young Adult”[MeSH Terms])) |

| ‘((“risk factor*”OR “prevention”) AND (“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”) AND (“social network*” OR “social media” OR “online social network*”) AND (“adolescent*” OR “young adult*”))’ in title and abstract, Publication Year is 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 |

| (title:(“risk factor*” OR “prevention”) OR abstract:(“risk factor*” OR “prevention”) OR keyword:(“risk factor*” OR “prevention”) OR field_of_study:(“risk factor*” OR “prevention”)) AND (title:(“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”) OR abstract:(“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”) OR keyword:(“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”) OR field_of_study:(“mental health” OR “mental disorder*”)) AND (title:(“social network*” OR “social media*”) OR abstract:(“social network*” OR “social media*”) OR keyword:(“social network*” OR “social media*”) OR field_of_study:(“social network*” OR “social media*”)) AND (title:(“adolescent*” OR “young adult*”) OR abstract:(“adolescent*” OR “young adult*”) OR keyword:(“adolescent*” OR “young adult*”) OR field_of_study:(“adolescent*” OR “young adult*”)) |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Original article or case study on social media and mental health | Non-original article or not a case study on social media and mental health |

| Focused on social media | Not focused on social media |

| Documented mental health risks | Undocumented mental health risks |

| Proposals for prevention of mental health issues | No proposals for prevention of mental health issues |

| Applied to adolescents and young adults | Applied to another age group |

| Full access to the publication | No access to the full publication |

| Written in English | Written in another language |

| Impact Dimension | Main Associated Mechanism | Key Finding Example (Reference Study) |

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Problematic use, social comparison, rumination | Greater social media use associated with more mental health symptoms (Beeres et al., 2021). |

| Suicidal Behavior | Normalization, dissemination, imitation of graphic content | Reinterpretation of suicide as a result of social pressure, not just mental illness (Abrutyn et al., 2020). |

| Cyberbullying | Problematic use as a key predictor of victimization and perpetration | Problematic use is the strongest predictor of cyberbullying in 42 countries (Craig et al., 2020). |

| Sleep Disturbances | Nighttime use, frequency of checking, displacement of rest time | Higher frequency of posting and checking social media associated with greater daytime sleepiness (Hamilton & Lee, 2021). |

| Body Image | Exposure to ideal models, influencers, and food advertising | Being female, preferring Twitter, and following food influencers associated with risk of eating disorders (Farias et al., 2024). |

| Substance Use | Exposure to content and access to providers through platforms | 2% of youths purchased drugs online, primarily through Instagram/Facebook (Oksanen et al., 2021). |

| General Well-being | Addiction, substitution of face-to-face interactions, lower quality emotional support | Emotional support on social media was associated with higher risk of depression, face-to-face with lower risk (Shensa et al., 2020). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabezas-Klinger, H.; Fernandez-Daza, F.F.; Mina-Paz, Y. Associations Between Social Media Use and Mental Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111450

Cabezas-Klinger H, Fernandez-Daza FF, Mina-Paz Y. Associations Between Social Media Use and Mental Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111450

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabezas-Klinger, Hector, Fabian Felipe Fernandez-Daza, and Yecid Mina-Paz. 2025. "Associations Between Social Media Use and Mental Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111450

APA StyleCabezas-Klinger, H., Fernandez-Daza, F. F., & Mina-Paz, Y. (2025). Associations Between Social Media Use and Mental Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111450