The Relationship Between Emotion Malleability Beliefs and School Adaptation of Middle School Boarders: A Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Implicit Theories of Emotion Scale

2.2.2. The Scale of School Adjustment for Junior High School Students

2.2.3. Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale

2.2.4. Peer Relationship Assessment Scale

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Tests for Differences in Demographic Variables

3.3. Correlation Analysis

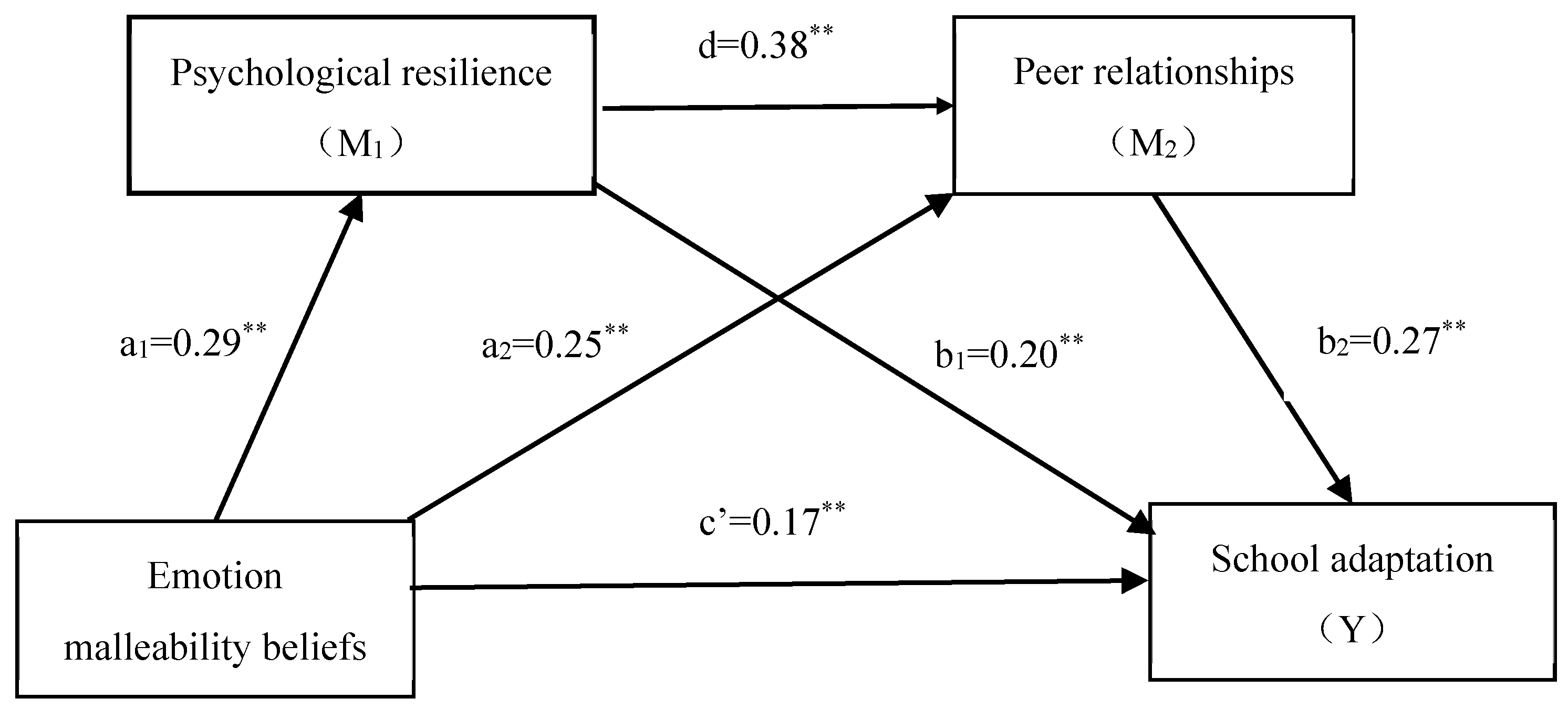

3.4. Chain Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Emotion Malleability Beliefs in School Adaptation

4.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships

4.3. Chain Mediating Effect of Resilience and Peer Relationships

4.4. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong, A. R., Galligan, R. F., & Critchley, C. R. (2011). Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience to negative life events. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S. R., Hymel, S., & Renshaw, P. D. (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55(4), 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailen, N. H., Green, L. M., & Thompson, R. J. (2018). Understanding emotion in adolescents: A review of emotional frequency, intensity, instability, and clarity. Emotion Review, 11(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, J. H. (2014). Andrew F. Hayes (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., & Finkel, E. J. (2012). Buffering against weight gain following dieting setbacks: An implicit theory intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(3), 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Xiao, S., Li, Y., Deng, Q., Gao, Y., & Gao, F. (2019). Relationship between shyness and middle school students’ adjustment: A mediated moderation model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 4, 790–794+799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congard, A., Le Vigouroux, S., Antoine, P., Andreotti, E., & Perret, P. (2022). Psychometric properties of a French version of the implicit theories of emotion scale. European Review of Applied Psychology, 72(1), 100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, S., Weinreb, K. S., Davila, G., & Cuellar, M. (2021). Relationships matter: The protective role of teacher and peer support in understanding school climate for victimized youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51(1), 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahò, M., & Monzani, D. (2025). The multifaceted nature of inner speech: Phenomenology, neural correlates, and implications for aphasia and psychopathology. Cognitive Neuropsychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castella, K., Goldin, P., Jazaieri, H., Ziv, M., Dweck, C. S., & Gross, J. J. (2013). Beliefs about emotion: Links to emotion regulation, well-being, and psychological distress. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(6), 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castella, K., Platow, M. J., Tamir, M., & Gross, J. J. (2018). Beliefs about emotion: Implications for avoidance-based emotion regulation and psychological health. Cogntion & Emotion, 32(4), 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eoh, Y., Lee, E., & Park, S. H. (2022). The relationship between children’s school adaptation, academic achievement, happiness, and problematic smartphone usage: A multiple informant moderated mediating model. Applied Research Quality Life, 17(6), 3579–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2018). Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., Lwi, S. J., Gentzler, A. L., Hankin, B., & Mauss, I. B. (2018). The cost of believing emotions are uncontrollable: Youths’ beliefs about emotion predict emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 147(8), 1170–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, A., Dahò, M., & Mancini, F. (2021). Emotional reasoning and psychopathology. Brain Sciences, 11(4), 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, M. (1998). Apprehension about communication and human resilience. Psychological Reports, 82(2), 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., & Imamoglu, A. (2021). Valuing emotional control in social anxiety disorder: A multimethod study of emotion beliefs and emotion regulation. Emotion, 21(4), 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, R., Turner, R., & Madill, A. (2016). Best friends and better coping: Facilitating psychological resilience through boys’ and girls’ closest friendships. British Journal of Psychology, 107(2), 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, S., Taylor, E. P., & Schwannauer, M. (2021). Positive peer relationships, coping and resilience in young people in alternative care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halilova, J. G., Ward Struthers, C., Guilfoyle, J. R., Shoikhedbrod, A., van Monsjou, E., & George, M. (2020). Does resilience help sustain relationships in the face of interpersonal transgressions? Personality and Individual Differences, 160, 109928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J. (2016). Development of the scale of school adjustment for junior high school student and its validity and reliability. China Journal of Health Psychology, 3, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., & Gan, Y. (2008). Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 8, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Cai, F., Liu, P., Zhang, W., & Gong, W. (2015). Parent-child relationship and school adjustment: The mediating of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1, 171–173+177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Ye, B., & Yang, Q. (2021). Effect of social and emotional competency on social adaptability of middle school students: The chain mediating role of self-esteem and peer relationship. China Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendziora, K., & Osher, D. (2016). Promoting children’s and adolescents’ social and emotional development: District adaptations of a theory of action. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Kim, S., & Yoon, S. (2024). Emotion malleability beliefs matter in emotion regulation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 38(6), 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klika, J. B., & Herrenkohl, T. I. (2013). A review of developmental research on resilience in maltreated children. Trauma Violence Abuse, 14(3), 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klizienė, I., Klizas, Š., Čižauskas, G., & Sipavičienė, S. (2018). Effects of a 7-month exercise intervention programme on the psychosocial adjustment and decrease of anxiety among adolescents. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 7(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E. T., & Dovidio, J. F. (2020). Emotion malleability beliefs and coping with the college transition. Emotion, 20(3), 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E. T., Dovidio, J. F., Joormann, J., & Clark, M. S. (2016a). Emotion malleability beliefs, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: Integrating affective and clinical science. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E. T., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Dovidio, J. F., & Gruber, J. (2016b). Beliefs about emotion’s malleability influence state emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 40(5), 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llistosella, M., Castellví, P., García-Ortiz, M., López-Hita, G., Torné, C., Ortiz, R., Guallart, E., Uña-Solbas, E., & Carlos Martín-Sánchez, J. (2024). Effectiveness of a resilience school-based intervention in adolescents at risk: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1478424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malagoli, C., Chiorri, C., Traverso, L., & Usai, M. C. (2022). Inhibition and individual differences in behavior and emotional regulation in adolescence. Psychological Research, 86(4), 1132–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E. C. A., Dekovic, M., van Londen, M., & Reitz, E. (2022). Parallel changes in positive youth development and self-awareness: The role of emotional self-regulation, self-esteem, and self-reflection. Prevention Science, 23(4), 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C., Master, A., Paunesku, D., Dweck, C. S., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Academic and emotional functioning in middle school: The role of implicit theories. Emotion, 14(2), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, H. S., Kneeland, E. T., Silverman, A. L., Beard, C., & Björgvinsson, T. (2018). Beliefs about the malleability of anxiety and general emotions and their relation to treatment outcomes in acute psychiatric treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(2), 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A., Gao, W., Gu, J., Zhang, J., & Yu, A. (2021). Parent-child communication inconsistency and school adaptation of boarding adolescents: Different mediation of two coping styles and its gender difference. Psychology: Techniques and Applications, 3, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., Yao, J., & Li, L. (2021). The relationship between emotional intelligence and school adaptation of middle school students: The mediating role of psychological resilience. Mental Health Education in Primary and Secondary School, 18, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q., & Chen, Y. (2007). A research for class environments’ influence on junior high school students’ school adjustment. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1, 51–52+55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Lu, W., Yuan, J., & Tian, L. (2018). The effects of self-esteem on adolescents’ aggression behavior: The moderating effects of peer relationship. Journal of Shandong Normal University (Natural), 4, 481–486. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., & Qin, Y. (2017). Rural education development in China: An annual report. Beijing Normal University Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L., Zou, W., & Wang, H. (2022). School adaptation and adolescent immigrant mental health: Mediation of positive academic emotions and conduct problems. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 967691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Wan, X., Yitian, Z., Duan, J., Huang, S., Fu, Y., & Wang, J. (2017). Analysis on the correlation between injury of adolescents and school and peer factors. Chinese Journal of Disease Control and Prevention, 6, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., & Zhang, J. (2005). Resilience: The psychological mechanism for recovery and growth during stress. Advances in Psychological Science, 5, 658–665. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., Liang, Z., Deng, H., & Lu, Z. (2014). Relations between perceptions of school climate and school adjustment of adolescents: A longitudinal study. Psychological Development and Education, 4, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Guo, S., Lipp, O. V., & Wang, M. (2023). Emotion malleability beliefs predict daily positive and negative affect in adolescents. Cognition & Emotion, 37(5), 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Guo, H., & Lin, D. (2019). A Study on the relationship between parent-child, peer, teacher-student relations and subjective well-being of adolescents. Psychological Development and Education, 4, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S., Ni, S., & Hamilton, K. (2020). Cognition malleability belief, emotion regulation and adolescent well-being: Examining a mediation model among migrant youth. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 8(1), 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H., Qu, Z., & Ye, Y. (2007). The characteristics of teacher-student relationships and its relationship with school adjustment of students. Psychological Development and Education, 4, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Gender | t(479) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (N = 210) | Female (N = 271) | |||

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 2.77 ± 0.90 | 2.99 ± 0.83 | −2.79 | 0.00 |

| Adaptation to school | 2.93 ± 0.74 | 2.96 ± 0.75 | −0.46 | 0.64 |

| Psychological resilience | 3.03 ± 0.74 | 3.15 ± 0.68 | −2.28 | 0.02 |

| Peer relationships | 2.98 ± 0.77 | 3.12 ± 0.75 | −1.95 | 0.05 |

| Variables | Grade | F(2.47) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seventh Grade (N = 152) | Eighth Grade (N = 143) | Ninth Grade (N = 186) | |||

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 2.87 ± 0.83 | 2.94 ± 0.88 | 2.87 ± 0.90 | 0.26 | 0.77 |

| Adaptation to school | 3.03 ± 0.69 | 3.01 ± 0.72 | 2.84 ± 0.79 | 3.44 | 0.03 |

| Psychological resilience | 3.14 ± 0.69 | 3.20 ± 0.66 | 2.99 ± 0.75 | 3.86 | 0.02 |

| Peer relationships | 3.04 ± 0.76 | 3.08 ± 0.78 | 3.05 ± 0.75 | 0.12 | 0.89 |

| Variables | M | SD | Emotion Malleability Beliefs | School Adaptation | Psychological Resilience | Peer Relationships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 2.89 | 0.87 | 1 | |||

| School adaptation | 2.95 | 0.74 | 0.38 ** | 1 | ||

| Psychological resilience | 3.10 | 0.71 | 0.36 ** | 0.39 ** | 1 | |

| Peer relationships | 3.06 | 0.76 | 0.42 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.46 ** | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Fitting Index | Significance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | R2 | F | β | SE | t | LL | UL | ||

| Psychological resilience | 0.38 | 0.14 | 26.57 ** | ||||||

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.01 | −0.06 | 0.18 | ||||

| Grade | −0.08 | 0.04 | −2.24 * | −0.15 | −0.01 | ||||

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 0.29 | 0.03 | 8.39 ** | 0.22 | 0.36 | ||||

| Peer relationship | 0.53 | 0.28 | 47.06 ** | ||||||

| Gender | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.53 * | 0.69 | 1.40 | ||||

| Grade | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.18 | 0.33 | ||||

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 0.25 | 0.04 | 6.91 ** | 0.24 | 0.41 | ||||

| Psychological resilience | 0.38 | 0.05 | 8.38 ** | 0.27 | 0.45 | ||||

| Adaptation to school | 0.53 | 0.28 | 36.44 ** | ||||||

| Gender | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.07 | −0.18 | 0.05 | ||||

| Grade | −0.08 | 0.03 | −2.32 * | −0.15 | −0.01 | ||||

| Emotion malleability beliefs | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.44 ** | 0.09 | 0.24 | ||||

| Psychological resilience | 0.20 | 0.05 | 4.15 ** | 0.10 | 0.29 | ||||

| Peer relationships | 0.27 | 0.04 | 6.00 ** | 0.18 | 0.36 | ||||

| Effect | Path | Effect Value | SE | LL | UL | Relative Mediation Effect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | Emotion malleability beliefs → Adaptation to school | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 51.84 |

| Indirect effect | Emotion malleability beliefs → Psychological resilience → Adaptation to school | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 17.75 |

| Emotion malleability beliefs → Peer relationships → Adaptation to school | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 21.19 | |

| Emotion malleability beliefs → Psychological resilience → Peer relationships → Adaptation to school | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 9.22 | |

| Total effect | Emotion malleability beliefs → Adaptation to school | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Y.; Zheng, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Meng, Y. The Relationship Between Emotion Malleability Beliefs and School Adaptation of Middle School Boarders: A Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111444

Han Y, Zheng S, Chen X, Zhang J, Meng Y. The Relationship Between Emotion Malleability Beliefs and School Adaptation of Middle School Boarders: A Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111444

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Yixuan, Shiyu Zheng, Xuehong Chen, Jing Zhang, and Yao Meng. 2025. "The Relationship Between Emotion Malleability Beliefs and School Adaptation of Middle School Boarders: A Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111444

APA StyleHan, Y., Zheng, S., Chen, X., Zhang, J., & Meng, Y. (2025). The Relationship Between Emotion Malleability Beliefs and School Adaptation of Middle School Boarders: A Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Peer Relationships. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111444