Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Predictors, and Relation to Infants’ Vocabulary Size

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sociolinguistic Context in Montreal

1.2. Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Motivations, and Predictors

1.3. How Parental Language Mixing Relates to Word Learning and Vocabulary Development

1.4. Our Studies

2. Study 1: Parental Language Mixing Amongst French-English Bilinguals

2.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Measures

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Language Mixing Scale Validity in Montreal

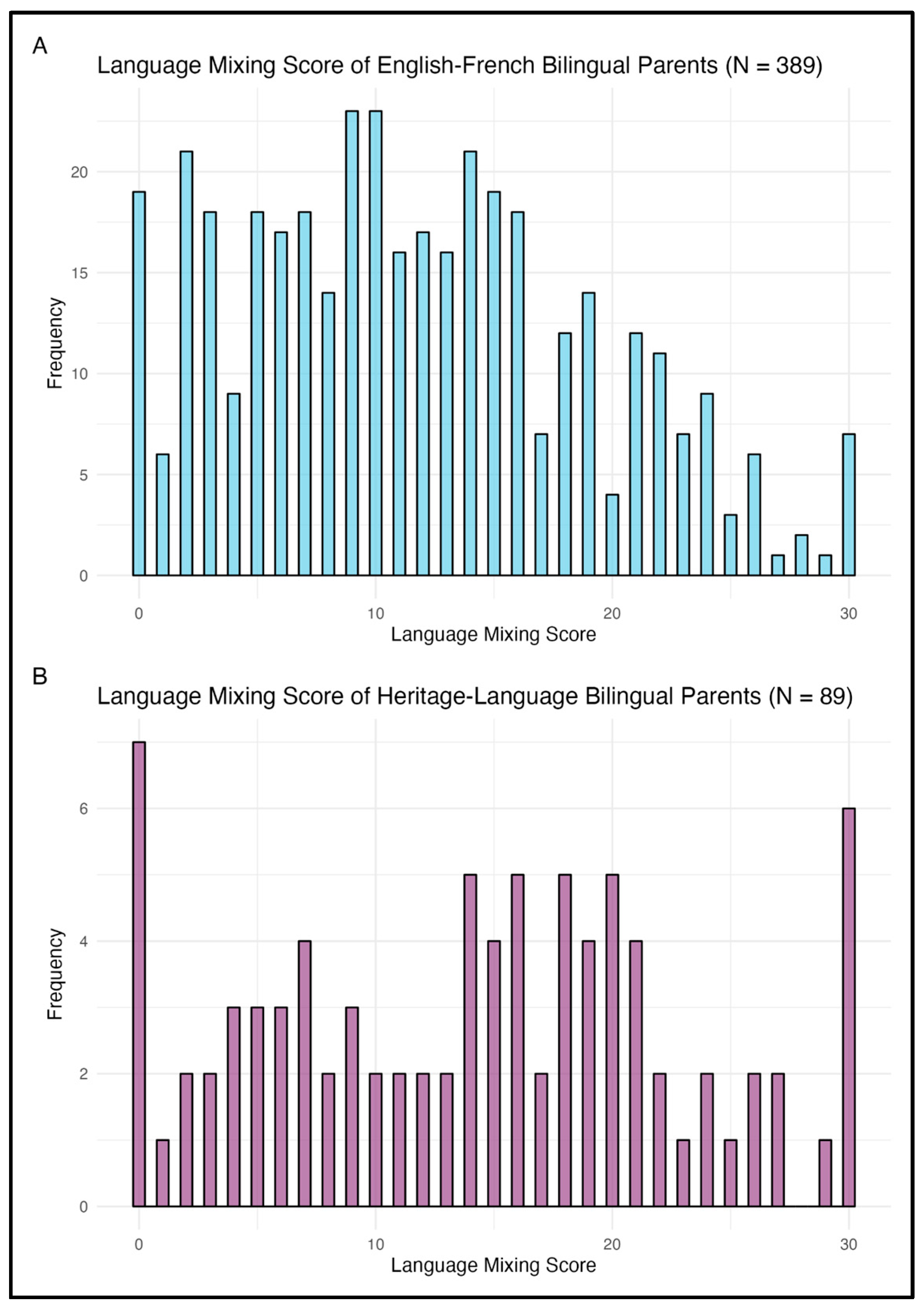

2.3.2. Prevalence of Language Mixing in Montreal and Comparisons to Other Communities

2.3.3. Parental Mixing Patterns

2.3.4. Motivations for Language Mixing and Relations to Child Age

2.3.5. Predictors of Language Mixing

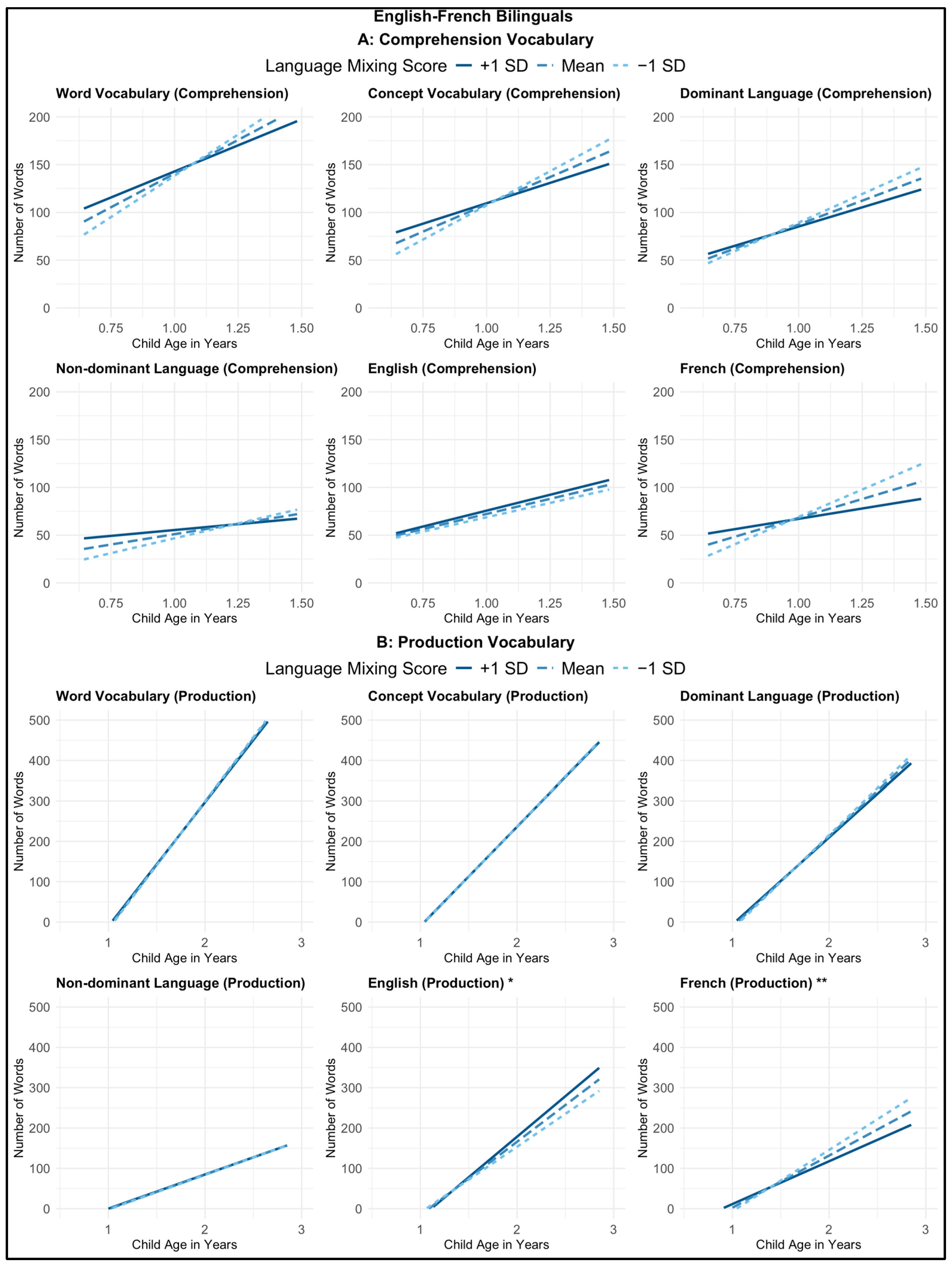

2.3.6. Parental Language Mixing’s Relationship to Children’s Vocabulary Size

2.4. Discussion

3. Study 2: Parental Language Mixing Amongst Heritage-Language Bilinguals

3.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

3.2. Methods

Participants

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Prevalence of Language Mixing

3.3.2. Parental Mixing Patterns

3.3.3. Reasons for Language Mixing and Relations to Child Age

3.3.4. Predictors of Language Mixing

3.3.5. Parental Language Mixing’s Relationship to Children’s Vocabulary Size

3.4. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Language Mixing Rates Vary by Sociolinguistic Context

4.2. Directional Patterns Reflect Language Dominance and Status

4.3. Pedagogical Motivations for Language Mixing

4.4. Limited Associations with Vocabulary Outcomes

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Percentages do not add up to 100 due to rounding. |

| 2 | Percentages do not add up to 53 due to rounding. |

| 3 | While we restricted the sample in Study 1 to parents of 18–30-month-olds to account for potential age differences with comparison groups, we were unable to do so in Study 2 due to the smaller sample size. |

References

- Abutalebi, J., Brambati, S. M., Annoni, J. M., Moro, A., Cappa, S. F., & Perani, D. (2007). The Neural Cost of the auditory perception of language switches: An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study in bilinguals. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(50), 13762–13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N. J., Graham, S. A., Prime, H., Jenkins, J. M., & Madigan, S. (2021). Linking quality and quantity of parental linguistic input to child language skills: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 92(2), 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bail, A., Morini, G., & Newman, R. S. (2015). Look at the gato! Code-switching in speech to toddlers. Journal of Child Language, 42(5), 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballinger, S., Brouillard, M., Ahooja, A., Kircher, R., Polka, L., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2020). Intersections of official and family language policy in Quebec. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43(7), 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergelson, E. (2020). The comprehension boost in early word learning: Older infants are better learners. Child Development Perspectives, 14(3), 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, L., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2001). Evidence of early language discrimination abilities in infants from bilingual environments. Infancy, 2(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, W. (2021). The functions of language mixing in the social networks of Singapore students. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2021(269), 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillard, M., Dubé, D., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2022). Reading to bilingual preschoolers: An experimental study of two book formats. Infant and Child Development, 31(3), e2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoy, T., & Nicoladis, E. (2018). The considerateness of codeswitching: A comparison of two groups of Canadian French-English bilinguals. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 47(4), 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers-Heinlein, K. (2013). Parental language mixing: Its measurement and the relation of mixed input to young bilingual children’s vocabulary size. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 16(1), 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers-Heinlein, K., Gonzalez-Barrero, A. M., Schott, E., & Killam, H. (2024). Sometimes larger, sometimes smaller: Measuring vocabulary in monolingual and bilingual infants and toddlers. First Language, 44(1), 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers-Heinlein, K., Jardak, A., Fourakis, E., & Lew-Williams, C. (2022). Effects of language mixing on bilingual children’s word learning. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 25(1), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers-Heinlein, K., Morin-Lessard, E., & Lew-Williams, C. (2017). Bilingual infants control their languages as they listen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(34), 9032–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers-Heinlein, K., Schott, E., Gonzalez-Barrero, A. M., Brouillard, M., Dubé, D., Jardak, A., Laoun-Rubenstein, A., Mastroberardino, M., Morin-Lessard, E., Iliaei, S. P., Salama-Siroishka, N., & Tamayo, M. P. (2019). MAPLE: A Multilingual Approach to Parent Language Estimates. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 23(5), 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2009). Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy, 8(4), 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, S., Byers-Heinlein, K., & Werker, J. F. (2011). Bilingual beginnings as a lens for theory development: PRIMIR in focus. Journal of Phonetics, 39(4), 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J., Kuiken, F., Jorna, R. J., & Klinkenberg, E. L. (2015). The role of majority and minority language input in the early development of a bilingual vocabulary. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 19(1), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenson, L. F., Marchman, M., Thal, D., Dale, P., Reznick, R., & Bates, B. (2007). MacArthur-bates communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual (2nd ed.). Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, V. C. M., & Thomas, E. M. (2009). Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 12(2), 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T. H., Schotter, E. R., Gomez, J., Murillo, M., & Rayner, K. (2014). Multiple levels of bilingual language control: Evidence from language intrusions in reading aloud. Psychological Science, 25(2), 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, F. (2021). Life as a bilingual: Knowing and using two or more languages (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. C., González, A. C. L., Girardin, M. G., & Almeida, A. M. (2022). Code-switching by Spanish–English bilingual children in a code-switching conversation sample: Roles of language proficiency, interlocutor behavior, and parent-reported code-switching experience. Languages, 7(4), 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerini, F. (2014). Language contact, language mixing and identity: The Akan spoken by Ghanaian immigrants in northern Italy. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(4), 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M., Crespo, K., & Neveu, A. (2022). Does code-switching influence novel word learning? Developmental Science, 26(2), e13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, A. (2010). What is a heritage language? Center for Applied Linguistics: Heritage Briefs. Available online: http://www.cal.org/heritage/pdfs/briefs/What-is-a-Heritage-Language.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kircher, R. (2009). Language attitudes in Quebec: A contemporary perspective. Available online: https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/497 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Kircher, R., Quirk, E., Brouillard, M., Ahooja, A., Ballinger, S., Polka, L., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2022). Quebec-based parents’ attitudes towards childhood multilingualism: Evaluative dimensions and potential predictors. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 41(5), 527–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremin, L. V., Alves, J., Orena, A. J., Polka, L., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2022). Code-switching in parents’ everyday speech to bilingual infants. Journal of Child Language, 49(4), 714–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2013). LMERTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects models. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Leimgruber, J. R., & Fernández-Mallat, V. (2021). Language attitudes and identity building in the linguistic landscape of Montreal. Open Linguistics, 7(1), 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C., & Chan, S. (2016). Direction matters: Event-related brain potentials reflect extra processing costs in switching from the dominant to the less dominant language. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 40, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libersky, E., Slawny, C., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2025). Learning in Dos Idiomas: The impact of codeswitching on children’s noun and verb learning. Infant and Child Development, 34(1), e2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchman, V. A., Martínez, L. Z., Hurtado, N., Grüter, T., & Fernald, A. (2017). Caregiver talk to young Spanish-English bilinguals: Comparing direct observation and parent-report measures of dual-language exposure. Developmental Science, 20(1), e12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, R. (2023). Bilingualism is good but codeswitching is bad: Attitudes about Spanish in contact with English in the Tijuana-San Diego border area. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 20(4), 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoladis, E., & Secco, G. (2000). The role of a child’s productive vocabulary in the language choice of a bilingual family. First Language, 20(58), 003-28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilep, C. (2006). “Code switching” in sociocultural linguistics. Colorado Research in Linguistics, 19(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, B. Z., Fernández, S. C., & Oller, D. K. (1993). Lexical development in bilingual infants and toddlers: Comparison to monolingual norms. Language Learning, 43(1), 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sabater, C., & Moffo, G. M. (2019). Managing identity in football communities on Facebook: Language preference and language mixing strategies. Lingua, 225, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J. S., Romero, I., Nava, M., & Huang, D. (2001). The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(2), 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S., & Hoff, E. (2016). Effects and noneffects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2 ½-year-olds. Bilingualism Language and Cognition, 19(5), 1023–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, C., & Stockemer, D. (2016). Anglicisms and students in Quebec: Oral, written, public, and private—Do personal opinions on language protection influence students’ use of English borrowings? International Journal of Canadian Studies, 54, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, C., & Stockemer, D. (2020). Anglicisms, French equivalents, and language attitudes among Quebec undergraduates. British Journal of Canadian Studies, 32(1–2), 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, S. (1985). Contrasting patterns of code-switching in two communities. Codeswitching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Available online: https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/6618 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Potter, C. E., Fourakis, E., Morin-Lessard, E., Byers-Heinlein, K., & Lew-Williams, C. (2019). Bilingual toddlers’ comprehension of mixed sentences is asymmetrical across their two languages. Developmental Science, 22(4), e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Read, K., Contreras, P. D., Rodriguez, B., & Jara, J. (2021). ¿Read conmigo?: The effect of code-switching storybooks on dual-language learners’ retention of new vocabulary. Early Education and Development, 32(4), 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. (2007). Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Rosseel, Y., Jorgensen, T. D., & De Wilde, L. (2012). Lavaan: Latent variable analysis. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lavaan/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Rowe, D. J. (2023). There are more English and allophone students in Quebec going to French school: OQLF study. CTVNews. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/montreal/article/there-are-more-english-and-allophone-students-in-quebec-going-to-french-school-oqlf-study/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Rowe, M. L., & Snow, C. E. (2019). Analyzing input quality along three dimensions: Interactive, linguistic, and conceptual. Journal of Child Language, 47(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salig, L. K., Kroff, J. R. V., Slevc, L. R., & Novick, J. M. (2025). Hearing a code-switch increases bilinguals’ attention to and memory for information. Journal of Memory and Language, 143, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, E., Kremin, L. V., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2022). The youngest bilingual Canadians: Insights from the 2016 census regarding children aged 0–9 years. Canadian Public Policy, 48(2), 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J. F., & Lew-Williams, C. (2016). Language learning, socioeconomic status, and child-directed speech. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Cognitive Science, 7(4), 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. (2023a). Census profile, 2021 census of population. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Statistics Canada. (2023b). English–French bilingualism in Canada: Recent trends after five decades of official bilingualism. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021013/98-200-x2021013-eng.cfm (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Tamargo, R. E. G., Kroff, J. R. V., & Dussias, P. E. (2016). Examining the relationship between comprehension and production processes in code-switched language. Journal of Memory and Language, 89, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trudeau, N., Frank, H., & Poulin-Dubois, D. (1999). Une adaptation en français Québécois du MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory. La Revue D’orthophonie et D’audiologie, 23(2), 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, R. K. Y., Kosie, J. E., Fibla, L., Lew-Williams, C., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2023). Patterns of language switching and bilingual children’s word learning: An experiment across two communities. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 9(4), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). Multilingual education: A key to quality and inclusive learning. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/multilingual-education-key-quality-and-inclusive-learning (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Unsworth, S. (2016). Quantity and quality of language input in bilingual language development. In De gruyter eBooks (pp. 103–122). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J., Kuiken, F., & Andringa, S. (2022). Family language patterns in bilingual families and relationships with children’s language outcomes. Applied Psycholinguistics, 43(5), 1109–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, E., van Witteloostuijn, M., Oudgenoeg-Paz, O., & Blom, E. (2025). To mix or not to mix? The relation between parental language mixing and bilingual children’s language outcomes. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Factor Loading | Inter-Item Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switch Dom → NonDom | Switch NonDom → Dom | Borrow Dom Word | Borrow NonDom Word | Mix Both Languages | ||||

| Switch Dom → NonDom | 1.93 | 1.81 | 0.77 | – | ||||

| Switch NonDom → Dom | 2.10 | 1.83 | 0.65 | 0.59 *** | – | |||

| Borrow Dom Word | 2.64 | 1.98 | 0.66 | 0.44 *** | 0.45 *** | – | ||

| Borrow NonDom Word | 2.32 | 1.84 | 0.74 | 0.62 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.54 *** | – | |

| Mix Both Languages | 2.60 | 1.93 | 0.75 | 0.61 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.53 *** | – |

| Borrowing Dominant Language Word When Speaking Non-Dominant Language | Borrowing Non-Dominant Language Word When Speaking Dominant Language | Borrowing English Word When Speaking French | Borrowing French Word When Speaking English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I’m not sure of the word | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.39 |

| No translation or only a poor translation exists for the word | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| The word is hard to pronounce | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| When I’m teaching new words | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| Other times/not sure | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Parameter | Unstandardized Estimate (B) | SE | Standardized Estimate (β) | t(385) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.58 | 1.69 | 0.66 | 2.12 | 0.035 |

| Parent balance score | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 8.95 | <0.001 |

| Number of contexts | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.319 |

| Child age in years | 1.46 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 2.62 | 0.009 |

| Borrowing Dominant Language Word When Speaking Non-Dominant Language | Borrowing Non-Dominant Language Word When Speaking Dominant Language | Borrowing Heritage Language Word When Speaking Societal Language | Borrowing Societal Language Word When Speaking Heritage Language | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I’m not sure of the word | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.45 |

| No translation or only a poor translation exists for the word | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.39 |

| The word is hard to pronounce | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.34 |

| When I’m teaching new words | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| Other times/not sure | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

| Unstandardized Estimate (B) | SE | Standardized Estimate (β) | t(85) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.30 | 3.36 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.929 |

| Parent balance score | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 3.50 | 0.001 |

| Number of contexts | 0.86 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 2.37 | 0.020 |

| Child age in years | 1.60 | 1.40 | 0.26 | 1.15 | 0.253 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paquette, A.; Byers-Heinlein, K. Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Predictors, and Relation to Infants’ Vocabulary Size. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101371

Paquette A, Byers-Heinlein K. Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Predictors, and Relation to Infants’ Vocabulary Size. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101371

Chicago/Turabian StylePaquette, Alexandra, and Krista Byers-Heinlein. 2025. "Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Predictors, and Relation to Infants’ Vocabulary Size" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101371

APA StylePaquette, A., & Byers-Heinlein, K. (2025). Parental Language Mixing in Montreal: Rates, Predictors, and Relation to Infants’ Vocabulary Size. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101371