The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence on Innovative Teaching Behaviors

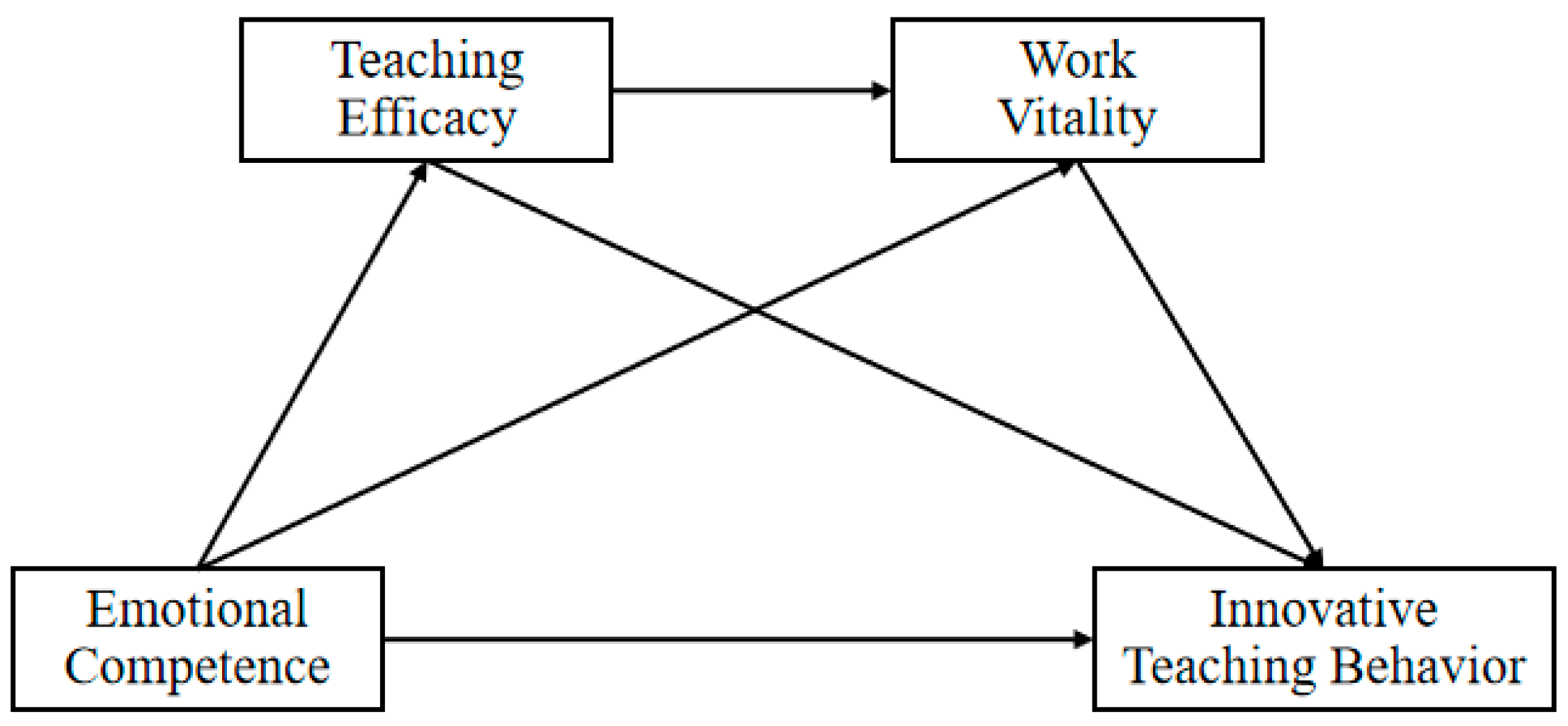

2.3. Independent Mediating Roles of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality

2.4. Chain-Mediated Effect of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality

2.5. Current Research

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Emotional Competence

3.2.2. Teaching Efficacy

3.2.3. Work Vitality

3.2.4. Innovative Teaching Behavior

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis Methods

3.4. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Testing the Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors

5.2. Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality

5.3. Contributions and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1.

- Sample Items from the Emotional Literacy Scale (7-point Likert scale):

- 2.

- Sample Items from the Teaching Efficacy Scale (7-point Likert scale):

- 3.

- Sample Items from the Work Vitality Scale (7-point Likert scale):

- 4.

- Sample Items from the Innovative Teaching Practices Scale (7-point Likert scale):

References

- Alemdar, M., & Anılan, H. (2020). The development and validation of the emotional literacy skills scale. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 7(2), 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., McKay, A. S., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Emotional intelligence and creativity: The mediating role of generosity and vigor. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 48(4), 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Lin, C., & Lin, F. (2024). The interplay among EFL teachers’ emotional intelligence and self-efficacy and burnout. Acta Psychologica, 248, 104364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, V. M. (2010). Tensions and dilemmas of teachers in creativity reform in a Chinese context. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 5(3), 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M., Altinay, L., & De Vita, G. (2018). Emotional intelligence and creative performance: Looking through the lens of environmental uncertainty and cultural intelligence. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 73, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R. W. (1997). The emotional contagion scale: A measure of individual differences. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 21(2), 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: A reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P. W. (2010). Emotional competence and its influences on teaching and learning. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorozidis, G. S., & Papaioannou, A. G. (2016). Teachers’ achievement goals and self-determination to engage in work tasks promoting educational innovations. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. (2001). Emotional geographies of teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1056–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussi, K. S., Knights, A. R., & Gupta, A. (2017). Feeling good, being intentional, and their relationship to two types of creativity at work. Creativity Research Journal, 29(4), 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., & Tong, Y. (2025). Emotional intelligence and innovative teaching behavior of pre-service music teachers: The chain mediating effects of psychological empowerment and career commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1557806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. K., & Le Fevre, D. M. (2021). Increasing teacher engagement in innovative learning environments: Understanding the effects of perceptions of risk. In Teacher transition into innovative learning environments (pp. 73–83). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Alive and creating: The mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(6), 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkkola, P., Kuittinen, M., & Hintsa, T. (2019). Role clarity, role conflict, and vitality at work: The role of the basic needs. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 60(5), 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliueva, E., & Tsagari, D. (2018). Emotional literacy in EFL classes: The relationship between teachers’ trait emotional intelligence level and the use of emotional literacy strategies. System, 78, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottmann, A., Schildkamp, K., & van der Meulen, B. (2024). Determinants of the innovation behaviour of teachers in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 49(2), 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazopoulou, M., Metsäpelto, R. L., Varis, S., Poikkeus, A. M., Tolvanen, A., Galanaki, E. P., & Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. (2025). Teacher education students’ emotional intelligence and teacher self-efficacy: A cross-cultural comparison. Current Psychology, 44(2), 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrusheva, O. (2020). The concept of vitality. Review of the vitality-related research domain. New Ideas in Psychology, 56, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Yin, H., Wang, Y., & Lu, J. (2024). Teacher innovation: Conceptualizations, methodologies, and theoretical framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 145, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maun, D., Chand, V. S., & Shukla, K. D. (2023). Influence of teacher innovative behaviour on students’ academic self-efficacy and intrinsic goal orientation. Educational Psychology, 43(6), 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review, 8(4), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S., & Extremera, N. (2017). Emotional intelligence and teacher burnout: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. V. T., Nguyen, H. T., Nong, T. X., & Nguyen, T. T. T. (2022). Inclusive leadership and creative teaching: The mediating role of knowledge sharing and innovative climate. Creativity Research Journal, 36(2), 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(3), 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2025). OECD Teaching Compass: Reimagining teachers as agents of curriculum changes. OECD Education Policy Papers, No. 123. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kamp, E. M., Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Demerouti, E. (2020). Proactive vitality management and creative work performance: The role of self-insight and social support. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(2), 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, M. R., Seo, M.-G., & Sherf, E. N. (2015). Regulating and facilitating: The role of emotional intelligence in maintaining and using positive affect for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazin, A. H., Maat, S. M., & Mahmud, M. S. (2022). Factors influencing teachers’ creative teaching: A systematic review. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 17(1), 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. S., & Garner, P. W. (2025). Teacher-student relationships: The roles of teachers’ emotional competence, social emotional learning beliefs, and burnout. Teachers and Teaching, 31(7), 1229–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). From ego depletion to vitality: Theory and findings concerning the facilitation of energy available to the self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, E., Fulton, C., & Beaton, C. (2025). Teacher emotional competence: A conceptual model. Educational Psychology Review, 37(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, N. N. (2019). Major factors of teachers’ resistance to innovations. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 27(104), 589–609. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, V. V., & Gutiérrez-Esteban, P. (2023). Challenges and enablers in the advancement of educational innovation. The forces at work in the transformation of education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 135, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, J., Thum, Y. M., & Zifkin, D. (2006). How much does creative teaching enhance elementary school students’ achievement? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 40(1), 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. (2011). Vigor as a positive affect at work: Conceptualizing vigor, its relations with related constructs, and its antecedents and consequences. Review of General Psychology, 15(1), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicki, C., Krishnakumar, S., & Robinson, M. D. (2023). Working with emotions: Emotional intelligence, performance and creativity in the knowledge-intensive workforce. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(2), 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S. Y., Rhee, Y. W., Lee, J. E., & Choi, J. N. (2020). Dual pathways of emotional competence towards incremental and radical creativity: Resource caravans through feedback-seeking frequency and breadth. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(3), 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyudi, M., Rahmatullah, A. S., Rachmawati, Y., & Hariyati, N. (2022). The effect of instructional leadership and creative teaching on student actualization: Student satisfaction as a mediator variable. International Journal of Instruction, 15(1), 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlings, M., Evers, A. T., & Vermeulen, M. (2015). Toward a model of explaining teachers’ innovative behavior: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 85(3), 430–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignjević Korotaj, B., & Mrnjaus, K. (2021). Emotional competence: A prerequisite for effective teaching. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiher, G. M., Varol, Y. Z., & Horz, H. (2022). Being tired or having much left undone: The relationship between fatigue and unfinished tasks with affective rumination and vitality in beginning teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 935775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Shen, J., Cropley, D. H., & Zheng, Y. (2025). A systematic review of factors influencing K-12 teachers’ creative teaching across different forms: An ecological perspective. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 57, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. L., Xin, T., & Shen, J. L. (1995). Teacher’s sense of teaching efficacy: Its structure and influencing factors. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 27(2), 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., & Zhang, L. (2012). Teacher’s innovative work behavior and innovation climate. Chinese Journal of Ergonomics, 18(3), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional competence | 6.15 | 0.68 | 1 | |||

| 2. Teaching efficacy | 5.38 | 0.79 | 0.63 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Work vitality | 5.41 | 0.83 | 0.63 *** | 0.68 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Innovative teaching behavior | 6.07 | 0.71 | 0.86 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.64 *** | 1 |

| Effect | β | SE | p | 95%CI | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | 0.14 | 0.02 | <0.001 | [0.14, 0.24] | |

| Indirect effect 1 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.001 | [0.01, 0.08] | 22.06% |

| Indirect effect 2 | 0.08 | 0.02 | <0.001 | [0.06, 0.11] | 58.82% |

| Indirect effect 3 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.002 | [0.04, 0.09] | 19.12% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Cheng, S.; Chen, N.; Wang, H. The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101357

Li X, Cheng S, Chen N, Wang H. The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101357

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xi, Si Cheng, Ning Chen, and Haibin Wang. 2025. "The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101357

APA StyleLi, X., Cheng, S., Chen, N., & Wang, H. (2025). The Promoting Role of Teachers’ Emotional Competence in Innovative Teaching Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Teaching Efficacy and Work Vitality. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101357