Understanding How Social Media Use Relates to Turnover Intention Among Chinese Civil Servants: A Resource Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Conservation of Resources Theory (COR)

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. ESMU, SMUNW, and Turnover Intention

3.2. The Mediating Role of Social Media Exhaustion

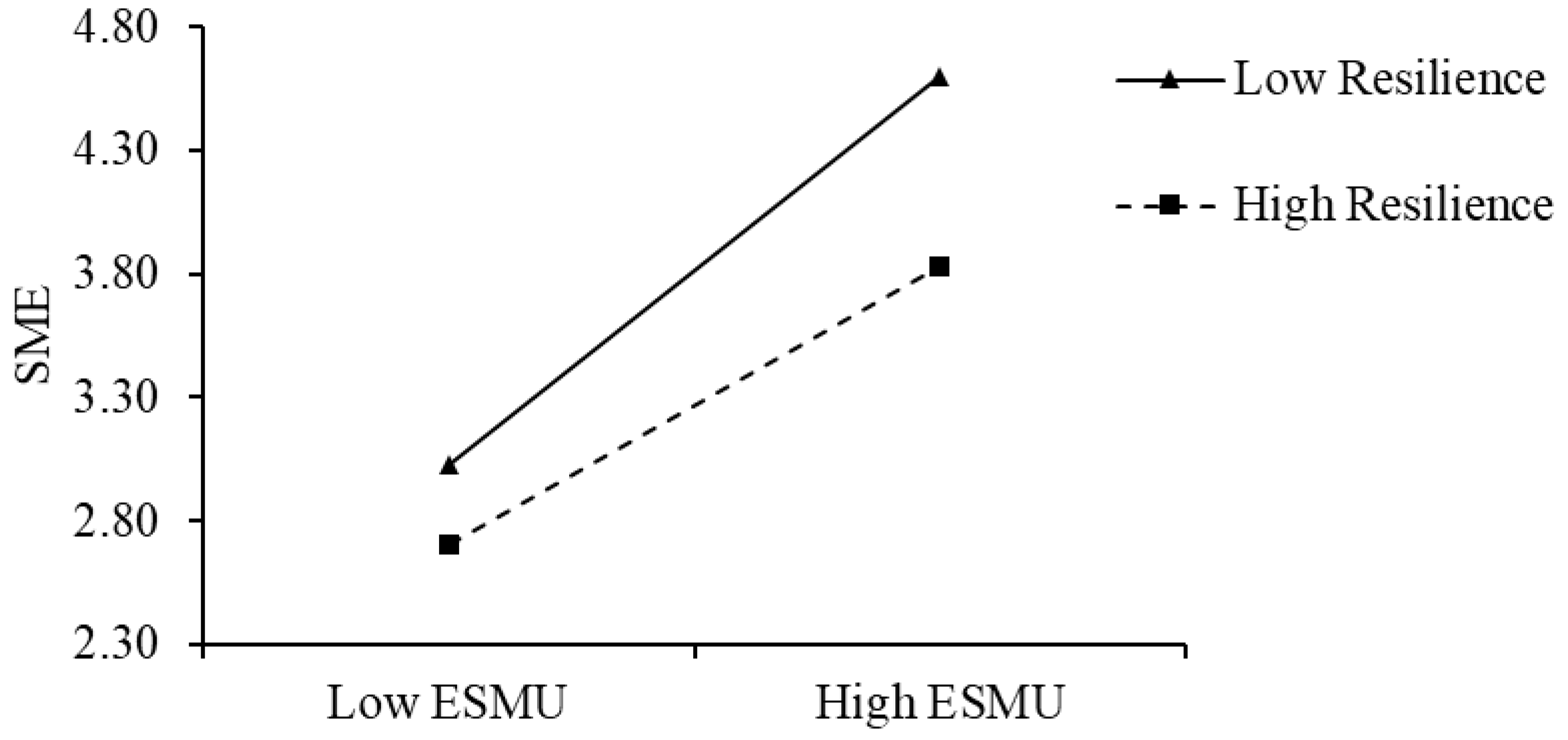

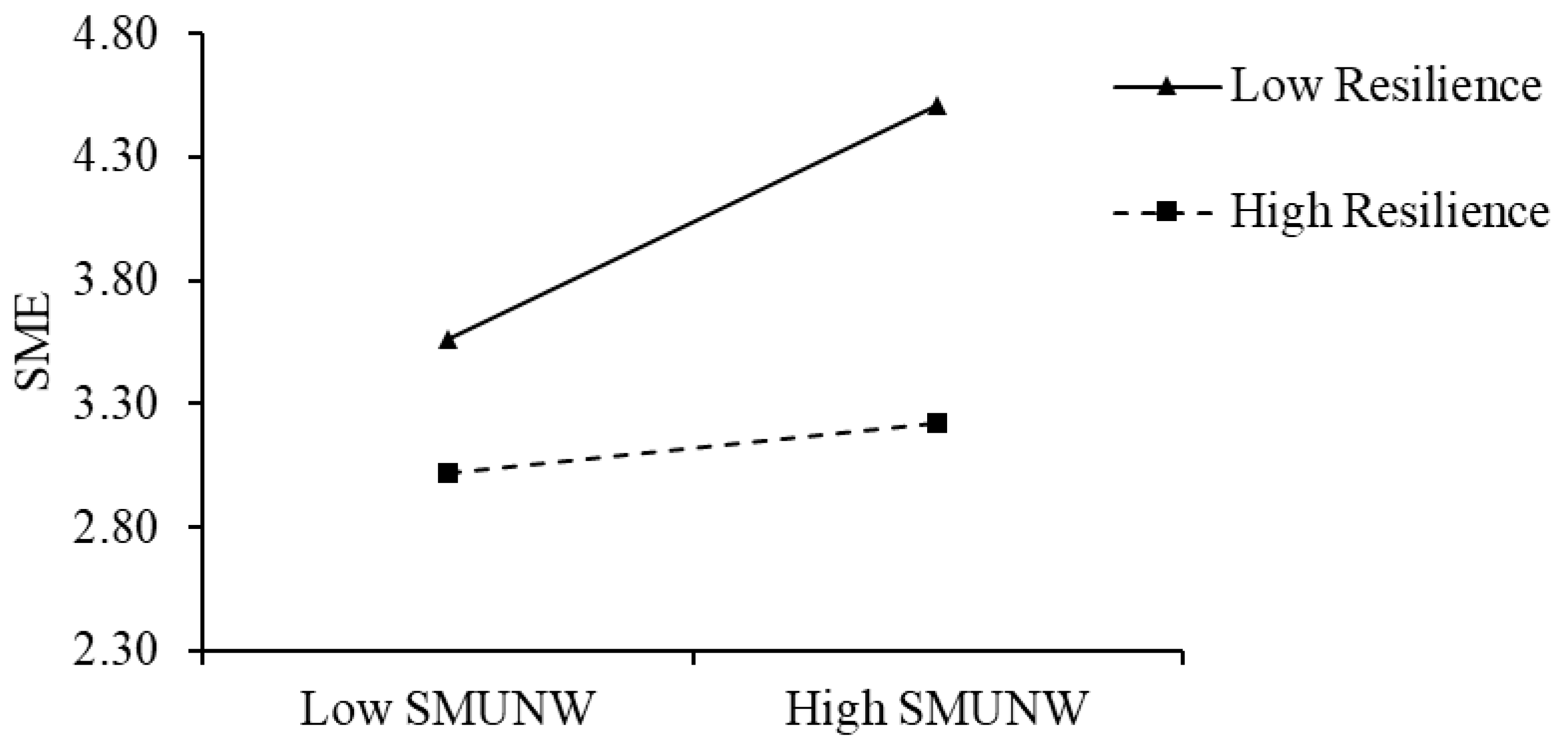

3.3. The Moderating Role of Resilience

4. Methods

4.1. Sample and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Excessive Social Media Use at Work

4.2.2. Social Media Use for Work During Non-Work Hours

4.2.3. Social Media Exhaustion

4.2.4. Resilience

4.2.5. Turnover Intention

4.2.6. Control Variables

4.3. Data Analysis Methods

4.4. Common Method Bias Test

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Excessive social media use at work |

| 1. I think the amount of time l spend using social media at work is excessive. |

| 2. I spend an unusually large amount of time using social media at work. |

| 3. I spend more time using social media at work than most other people. |

| Social media use for work during non-work hours |

| 1. I often use social media to connect with colleagues for work during non-work hours. |

| 2. I felt obliged to respond to work-related messages from social media during non-work hours. |

| 3. I often use social media to obtain work related information and knowledge during non-work hours. |

| 4. I’m used to checking work related information on social media during non-work hours. |

| Social media exhaustion |

| 1. I feel drained from activities that require me to use social media. |

| 2. I feel tired from my social media activities. |

| 3. Working all day with social media is a strain for me. |

| 4. I feel burned out from my social media activities. |

| Resilience |

| 1. When I have a setback at work, I have trouble recovering from it, moving on. (R) |

| 2. I usually manage difficulties one way or another at work. |

| 3. I can be “on my own,” so to speak, at work if I have to. |

| 4. I usually take stressful things at work in stride. |

| 5. I can get through difficult times at work because I’ve experienced difficulty before. |

| 6. I feel I can handle many things at a time at this job. |

| Turnover intention |

| 1. I often think of leaving this organization. |

| 2. It is very possible that I will look for a new job next year. |

| 3. Recently, I often think of changing the current job. |

References

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Al Balushi, A. K., Thumiki, V. R. R., Nawaz, N., Jurcic, A., & Gajenderan, V. (2022). Role of organizational commitment in career growth and turnover intention in public sector of Oman. PLoS ONE, 17(5), e0265535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Hassan, H., Nevo, D., & Wade, M. (2015). Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 24(2), 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M., Li, M., Hussain, A., Jameel, A., & Hu, W. (2023). Impact of perceived supervisor support and leader-member exchange on employees’ intention to leave in public sector museums: A parallel mediation approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1131896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardoel, E. A., & Drago, R. (2021). Acceptance and strategic resilience: An application of conservation of resources theory. Group & Organization Management, 46(4), 657–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzi, L. (2018). The hidden problem of Facebook and social media at work: What if employees start searching for other jobs? Business Horizons, 61(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J. G. (2016). Do transformational leaders affect turnover intentions and extra-role behaviors through mission valence? The American Review of Public Administration, 46(2), 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., & Yu, L. (2019). Exploring the influence of excessive social media use at work: A three-dimension usage perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J., Lee, H. E., & Kim, H. (2019). Effects of communication-oriented overload in mobile instant messaging on role stressors, burnout, and turnover intention in the workplace. International Journal of Communication, 13, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y. (2018). Abusive supervision and social network service addiction. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(2), 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, N. N., Nonterah, C. W., Utsey, S. O., Hook, J. N., Hubbard, R. R., Opare-Henaku, A., & Fischer, N. L. (2015). Predictor and moderator effects of ego resilience and mindfulness on the relationship between academic stress and psychological well-being in a sample of Ghanaian college students. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(4), 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, T., Hinsley, A. W., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2010). Who interacts on the web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., Peters, P., & van Wingerden, P. (2016). Work-related smartphone use, work–family conflict and family role performance: The role of segmentation preference. Human Relations, 69(5), 1045–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z., Bao, Y., & Hua, M. (2024). Social media use for work during non-work hours and turnover intention: The mediating role of burnout and the moderating role of resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1391554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S., Li, H., Liu, Y., Pirkkalainen, H., & Salo, M. (2020). Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Information Processing & Management, 57(6), 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Dia, M. J., DiNapoli, J. M., Garcia-Ona, L., Jakubowski, R., & O’FLaherty, D. (2013). Concept analysis: Resilience. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(6), 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Izquierdo, M., de Pedro, M. M., Ríos-Risquez, M. I., & Sánchez, M. I. S. (2018). Resilience as a moderator of psychological health in situations of chronic stress (burnout) in a sample of hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(2), 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, W., & Hecht, T. D. (2013). Work-family conflicts, threat-appraisal, self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(2), 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S. V., Sun, I. Y., Wu, Y., & Chen, Y. (2024). Gender differences in Chinese policing: Supervisor support, wellbeing, and turnover intention. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 18, paae028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Herttalampi, M., & Feldt, T. (2023). A new approach to stress of conscience’s dimensionality: Hindrance and violation stressors and their role in experiencing burnout and turnover intentions in healthcare. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(19–20), 7284–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Freedy, J. (2017). Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In Professional burnout (pp. 115–129). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L. W., Avey, J. B., & Nixon, D. R. (2010). Relationships between leadership and followers’ quitting intentions and job search behaviors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(4), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, W., Gulzar, A., & Aqeel, M. (2016). The mediating role of depression, anxiety and stress between job strain and turnover intentions among male and female teachers. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, S., Shand, F., Tighe, J., Laurent, S. J., A Bryant, R., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open, 8(6), e017858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, B., & Li, J. (2019). Exploring the impact of training, job tenure, and education-job and skills-job matches on employee turnover intention. European Journal of Training and Development, 43(3/4), 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A., Chaker, N. N., Singh, R., Itani, O. S., & Agnihotri, R. (2023). A desire for success: Exploring the roles of personal and job resources in determining the outcomes of salesperson social media use. Industrial Marketing Management, 113, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, N., Nizam Bin Isha, A. S., Salleh, R. B., Kanwal, N., & Al-Mekhlafi, A.-B. A. (2023). Paradoxical effects of social media use on workplace interpersonal conflicts. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2200892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimikia, H., Singh, H., & Joseph, D. (2020). Negative outcomes of ICT use at work: Meta-analytic evidence and the role of job autonomy. Internet Research, 31(1), 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2018). The contrary effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on burnout and turnover intention in the public sector. International Journal of Manpower, 39(3), 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftheriotis, I., & Giannakos, M. N. (2014). Using social media for work: Losing your time or improving your work? Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y., Hew, T.-S., Ooi, K.-B., Lee, V.-H., & Hew, J.-J. (2019). A hybrid SEM-neural network analysis of social media addiction. Expert Systems with Applications, 133, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.-G. (1999). Fairness in Chinese organizations. Old Dominion University. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. M., & Yuan, Q. (2015). The evolution of information and communication technology in public administration. Public Administration and Development, 35(2), 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C., Ranzini, G., & Meckel, M. (2014). Stress 2.0: Social media overload among Swiss teenagers. In Communication and information technologies annual (pp. 3–24). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Zhang, X., Tan, B. C., & Hao, F. (2023). Curvilinear relationship between social media use and job performance: A media synchronicity perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology, 43(8), 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C., Laumer, S., Weinert, C., & Weitzel, T. (2015). The effects of technostress and switching stress on discontinued use of social networking services: A study of Facebook use. Information Systems Journal, 25(3), 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M., Bartelt, V. L., Topuz, K., & Gehrt, K. L. (2020). Enterprise social media: Combating turnover in businesses. Internet Research, 30(2), 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm-Fischbacher, S., & Ehlert, U. (2014). Dispositional resilience as a moderator of the relationship between chronic stress and irregular menstrual cycle. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 35(2), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, J. M. G., Abd Manaf, N. H., Nor Filzatun, B., & Azahadi, M. O. (2014). Turnover intention among public sector health workforce: Is job satisfaction the issue? IIUM Medical Journal Malaysia, 13(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T. A., Sarwar, A., Khan, N., Tabash, M. I., & Hossain, M. I. (2023). Does emotional exhaustion influence turnover intention among early-career employees? A moderated-mediation study on Malaysian SMEs. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2242158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A., Memon, S. B., & Maitlo, A. A. (2021). Workplace incivility and turnover intention among nurses of public healthcare system in Pakistan. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 12(5), 1394–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saris, W. E., & Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14(3), 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2017). “Sore eyes and distracted” or “excited and confident”?—The role of perceived negative consequences of using ICT for perceived usefulness and self-efficacy. Computers & Education, 115, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M. H. M., Troshani, I., & Davidson, R. (2015). Public sector adoption of social media. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 55(4), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C., Yu, L., Wang, N., Cheng, B., & Cao, X. (2020). Effects of social media overload on academic performance: A stressor–strain–outcome perspective. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(2), 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L., Du, J., Cheng, G., Liu, X., Xiong, Z., & Luo, J. (2022). Cross-media search method based on complementary attention and generative adversarial network for social networks. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 37(8), 4393–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. (1989). Burnout in work organizations. In C. L. Cooper, & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology 1989 (pp. 25–48). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, S., Buvaneswari, G. M., & Arumugam, M. (2021). Resilience as a moderator of stress and burnout: A study of women social workers in India. International Social Work, 64(1), 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., & Wang, W. (2017). Transformational leadership, employee turnover intention, and actual voluntary turnover in public organizations. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Ren, S., Chadee, D., & Yuan, S. (2020). The dark side of social media connectivity: Influence on turnover intentions of supply chain professionals. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(5), 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, V., Brinkman, W.-P., Morina, N., & Neerincx, M. A. (2014). Characteristics of successful technological interventions in mental resilience training. Journal of Medical Systems, 38(9), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Liao, Y., Chen, M., Zhang, L., & Qian, J. (2023). Work and affective outcomes of social media use at work: A daily-survey study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(5), 941–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Li, Y. (2023). Social media use for work during non-work hours and work engagement: Effects of work-family conflict and public service motivation. Government Information Quarterly, 40(3), 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T., & Llave, O. V. (2021). Right to disconnect: Exploring company practices|VOCED plus, the international tertiary education and research database. Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A91561 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Whelan, E., Najmul Islam, A. K. M., & Brooks, S. (2020). Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Research, 30(3), 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. A., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2004). Commitment, psychological well-being and job performance: An examination of conservation of resources (COR) theory and job burnout. Journal of Business and Management, 9(4), 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Zhang, Y., Huang, S., & Yuan, Q. (2021). Does enterprise social media usage make the employee more productive? A meta-analysis. Telematics and Informatics, 60, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Cao, X., Liu, Z., & Wang, J. (2018). Excessive social media use at work: Exploring the effects of social media overload on job performance. Information Technology & People, 31(6), 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Khan, I., Dagar, V., Saeed, A., & Zafar, M. W. (2022). Environmental impact of information and communication technology: Unveiling the role of education in developing countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 178, 121570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Ma, L., Xu, B., & Xu, F. (2019). How social media usage affects employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intention: An empirical study in China. Information & Management, 56(6), 103136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 369 | 0.81 |

| Male | 84 | 0.19 | |

| Age | 21–29 | 160 | 0.35 |

| 30–39 | 169 | 0.37 | |

| 40–49 | 70 | 0.16 | |

| 50–60 | 54 | 0.12 | |

| Tenure | 1–5 | 136 | 0.30 |

| 6–10 | 118 | 0.26 | |

| 11–15 | 66 | 0.15 | |

| 16–20 | 39 | 0.09 | |

| 21–30 | 52 | 0.11 | |

| 31–45 | 42 | 0.09 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 116 | 0.26 |

| Married | 337 | 0.74 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hypothesized 5-factor model | ESMU, SMUNW, SME, Resilience, TI | 420.80 | 146 | 2.88 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| 2. Alternative 4-factor model | ESMU + SMUNW, SME, Resilience, TI | 809.82 | 150 | 5.40 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| 3. Alternative 3-factor model | ESMU + SMUNW, SME + Resilience, TI | 1336.40 | 153 | 8.73 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 4. Alternative 2-factor model | ESMU + SMUNW + SME + Resilience, TI | 2079.48 | 155 | 13.42 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| 5. Alternative 1-factor model | ESMU + SMUNW + SME + Resilience + TI | 3016.17 | 156 | 19.33 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.19 | 0.39 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 35.08 | 9.26 | 0.21 *** | - | |||||||

| 3. Tenure | 12.62 | 10.09 | 0.22 *** | 0.94 *** | - | ||||||

| 4. Marital status | 1.74 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 0.52 *** | 0.48 *** | - | |||||

| 5. ESMU | 3.72 | 1.13 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.04 | (0.89) | ||||

| 6. SMUNW | 4.45 | 0.92 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.51 *** | (0.83) | |||

| 7. SME | 3.57 | 1.28 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.57 *** | 0.22 *** | (0.95) | ||

| 8. Resilience | 4.22 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.15 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.17 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.05 | −0.32 *** | (0.68) | |

| 9. TI | 3.13 | 1.39 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.44 *** | 0.15 ** | 0.49 *** | −0.42 *** | (0.92) |

| SME | TI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | ||

| Gender | 0.00 (0.13) | −0.01 (0.16) | −0.03 (0.16) | −0.03 (0.15) | −0.04 (0.17) | −0.04 (0.15) | |

| Age | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.02) | −0.12 (0.02) | −0.17 (0.02) | −0.073(0.02) | −0.16 (0.02) | |

| Tenure | −0.13 (0.02) | −0.17 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.02) | |

| Marital status | 0.06 (0.13) | 0.04 (0.16) | −0.09 (0.15) | −0.09 * (0.14) | −0.09 (0.17) | −0.10 (0.15) | |

| ESMU | 0.57 *** (0.04) | 0.42 *** (0.05) | 0.21 *** (0.06) | ||||

| SMUNW | 0.22 *** (0.07) | 0.14 ** (0.07) | 0.04 (0.06) | ||||

| SME | 0.38 *** (0.05) | 0.49 *** (0.05) | |||||

| R2 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.26 | |

| ∆R2 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.23 | |

| F | 44.48 *** | 4.90 *** | 21.19 *** | 30.52 *** | 3.02 *** | 26.38 *** | |

| SME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Gender | 0.01 (0.13) | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.17) | 0.03 (0.14) |

| Age | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.02) |

| Tenure | −0.13 (0.01) | −0.10 (0.01) | −0.17 (0.02) | −0.10 (0.02) |

| Marital status | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.08 (0.15) | 0.10 (0.15) |

| ESMU | 0.52 *** (0.05) | 0.53 *** (0.04) | ||

| SMUNW | 0.24 *** (0.06) | 0.23 *** (0.05) | ||

| Resilience | −0.20 *** (0.05) | −0.21 *** (0.07) | −0.36 *** (0.06) | −0.36 *** (0.06) |

| ESMU ∗ Resilience | −0.11 ** (0.04) | |||

| SMUNW ∗ Resilience | −0.21 *** (0.04) | |||

| R2 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.22 |

| ∆R2 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| F | 43.57 *** | 39.17 *** | 15.61 *** | 17.64 *** |

| ESMU——>SME——>Turnover Intention | ||||

| Resilience | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| 3.475 (M − SD) | 0.278 | 0.050 | 0.184 | 0.379 |

| 4.222 (M) | 0.238 | 0.044 | 0.159 | 0.330 |

| 4.970 (M + SD) | 0.199 | 0.044 | 0.123 | 0.294 |

| Moderated mediation | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| −0.053 | 0.023 | −0.095 | −0.006 | |

| SMUNW——>SME——>Turnover Intention | ||||

| Resilience | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| 3.475 (M − SD) | 0.274 | 0.047 | 0.182 | 0.365 |

| 4.222 (M) | 0.166 | 0.039 | 0.088 | 0.241 |

| 4.970 (M + SD) | 0.058 | 0.049 | −0.041 | 0.149 |

| Moderated mediation | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| −0.145 | 0.036 | −0.215 | −0.073 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hua, M.; Bao, Y. Understanding How Social Media Use Relates to Turnover Intention Among Chinese Civil Servants: A Resource Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101331

Hua M, Bao Y. Understanding How Social Media Use Relates to Turnover Intention Among Chinese Civil Servants: A Resource Perspective. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101331

Chicago/Turabian StyleHua, Min, and Yuanjie Bao. 2025. "Understanding How Social Media Use Relates to Turnover Intention Among Chinese Civil Servants: A Resource Perspective" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101331

APA StyleHua, M., & Bao, Y. (2025). Understanding How Social Media Use Relates to Turnover Intention Among Chinese Civil Servants: A Resource Perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101331