The Strength of Vulnerability: How Does Supervisors’ Emotional Support-Seeking Promote Leadership Influence?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Emotional Support-Seeking and Leadership Influence

2.2. Supervisors’ LMX Efficiency as a Mediator

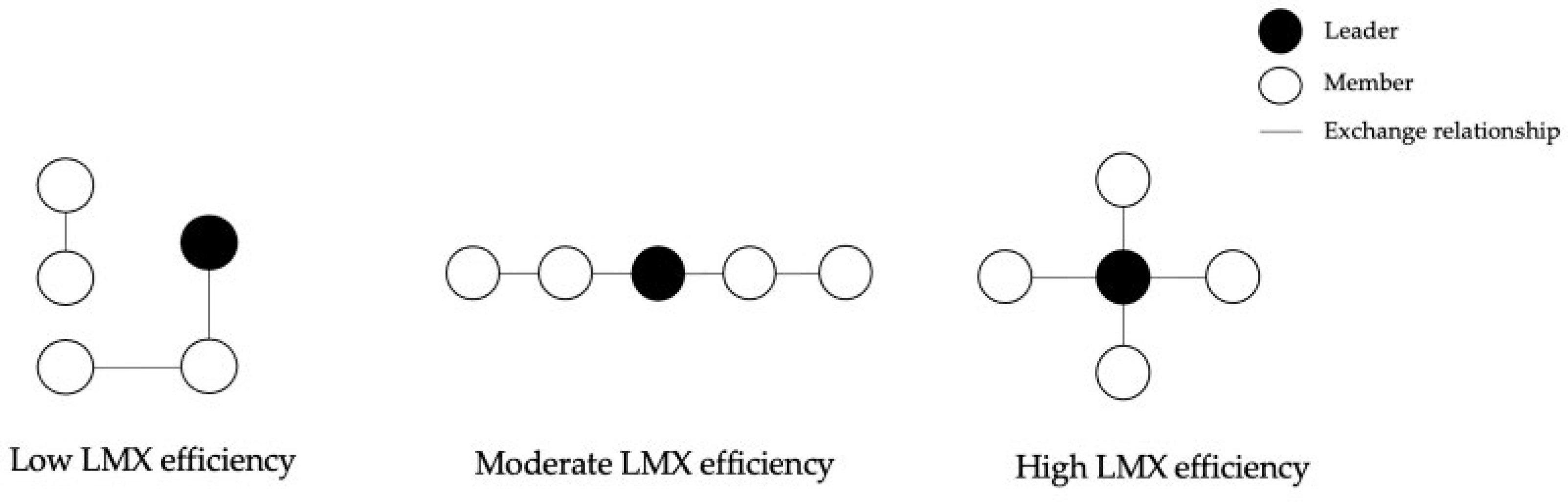

2.2.1. LMX Efficiency

2.2.2. LMX Efficiency as a Mediator

2.3. Managerial Competence as a Moderator

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Social Network Measures

3.2.2. Organizational Behavior Measures

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Contribution

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMX | Leader–Member Exchange |

| ILT | Implicit Leadership Theory |

References

- Berkovich, I., & Eyal, O. (2018). Help me if you can: Psychological distance and help-seeking intentions in employee–supervisor relations. Stress and Health, 34(3), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A. W., Huang, K., Abi-Esber, N., Buell, R. W., Huang, L., & Hall, B. (2019). Mitigating malicious envy: Why successful individuals should reveal their failures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buengeler, C., Piccolo, R. F., & Locklear, L. R. (2021). LMX differentiation and group outcomes: A framework and review drawing on group diversity insights. Journal of Management, 47(1), 260–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R. S. (2007). Secondhand brokerage: Evidence on the importance of local structure for managers, bankers, and analysts. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E., Leroy, H., Johnson, A., & Nguyen, H. (2022). Flaws and all: How mindfulness reduces error hiding by enhancing authentic functioning. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, S., Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., & Miners, C. T. H. (2010). Emotional intelligence and leadership emergence in small groups. Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, B., Thomas-Hunt, M. C., & Kesebir, S. (2019). To disclose or not to disclose: The ironic effects of the disclosure of personal information about ethnically distinct newcomers to a team. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. G., Brazeau, H., Xie, E. B., & McKee, K. (2021). Secrets, psychological health, and the fear of discovery. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D. R., Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1995). Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral complexity in managerial leadership. Organization Science, 6(5), 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., & Ashford, S. J. (2015). Interpersonal perceptions and the emergence of leadership structures in groups: A network perspective. Organization Science, 26(4), 1192–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddams, M., & Chang, G. C. (2012). Only human: Exploring the nature of weakness in authentic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership theory as a determinant of the factor structure underlying supervisory behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(6), 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2004). Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(2), 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farh, C. I. C., Bartol, K. M., Shapiro, D. L., & Shin, J. (2010). Networking abroad: A process model of how expatriates form support ties to facilitate adjustment. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 434–454. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, R. J., Hansbrough, T. K., Epitropaki, O., & Coyle, P. T. (2017). Dynamic viewpoints on implicit leadership and followership theories: Approaches, findings, and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 28(2), 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Liu, Y., Zhao, C., Fu, Y., & Schriesheim, C. A. (2024). Winter is coming: An investigation of vigilant leadership, antecedents, and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(6), 850–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F. H., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., Voelpel, S. C., & Van Vugt, M. (2019). It’s not just what is said, but when it’s said: A temporal account of verbal behaviors and emergent leadership in self-managed teams. Academy of Management Journal, 62(3), 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K. R. (2018). Can I tell you something? How disruptive self-disclosure changes who ‘we’ are. Academy of Management Review, 43(4), 570–589. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, K. R., Harari, D., & Marr, J. C. (2018). When sharing hurts: How and why self-disclosing weakness undermines the task-oriented relationships of higher status disclosers. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G. B., Hui, C., & Taylor, E. T. (2004). A new approach to team leadership: Upward, downward and horizontal differentiation. In G. B. Graen (Ed.), New frontiers of leadership, LMX leadership: The series (Vol. 2). Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, C. N. (2014). Emotional roulette? Symmetrical and asymmetrical emotion regulation outcomes from coworker interactions about positive and negative work events. Human Relations, 67(9), 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S., Mahsud, R., Yukl, G., & Prussia, G. E. (2013). Ethical and empowering leadership and leader effectiveness. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(2), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W., Fehr, R., Yam, K. C., Long, L. R., & Hao, P. (2017). Interactional justice, leader–member exchange, and employee performance: Examining the moderating role of justice differentiation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(4), 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, A. L., Ingold, P. V., & Kleinmann, M. (2020). Tell us about your leadership style: A structured interview approach for assessing leadership behavior constructs. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(4), 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W., Zhang, L., & Gajendran, R. S. (2024). Relative status and dyadic help seeking and giving: The roles of past helping history and power distance value. Human Relations, 77(5), 680–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Zhang, Z., Jiang, K., & Chen, W. (2019). Getting ahead, getting along, and getting prosocial: Examining extraversion facets, peer reactions, and leadership emergence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(11), 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Parker, M. R., Peterson, R. S., & Simon, G. (2024). Faking it with the boss’s jokes? Leader humor quantity, follower surface acting, and power distance. Academy of Management Journal, 67(5), 1175–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., John, L. K., Boghrati, R., & Kouchaki, M. (2022). Fostering perceptions of authenticity via sensitive self-disclosure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 28, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Yin, D., Liu, D., & Johnson, R. (2023). The more enthusiastic, the better? Unveiling a negative pathway from entrepreneurs’ displayed enthusiasm to funders’ funding intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(4), 1356–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. K., Huang, X., & Chan, S. C. (2015). The threshold effect of participative leadership and the role of leader information sharing. Academy of Management Journal, 58(3), 836–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Yu, G., Yang, J., Qi, Z., & Fu, K. (2014). Authentic leadership, traditionality, and interactional justice in the Chinese context. Management and Organization Review, 10(2), 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N., Zheng, X., Ni, D., Li, N., Zheng, X., Ni, D., Kirkman, B. L., Zhang, M., Xu, M., & Liu, C. (2025). Leadership in a crisis: A social network perspective on leader brokerage strategy, intra-organizational communication patterns, and business recovery. Journal of Management, 51(5), 2041–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W., Chia, R. C., & Fang, L. (2000). Chinese implicit leadership theory. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(6), 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L., Hinojosa, A., & Lynch, J. (2017). Make them feel: How the disclosure of pregnancy to a supervisor leads to changes in perceived supervisor support. Organization Science, 28(4), 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Perrewe, P. L. (2006). Are they for real? The interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes of perceived authenticity. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 1(3), 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R. G., Brown, D. J., Harvey, J. L., & Hall, R. J. (2001). Contextual constraints on prototype generation and their multilevel consequences for leadership perceptions. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(3), 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R. G., Foti, R. J., & Phillips, J. S. (1982). A theory of leadership categorization. In J. Hunt, U. Sekaran, & C. Schriesheim (Eds.), Leadership: Beyond establishment views (pp. 104–121). Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. D. (2005). Particularistic trust and general trust: A network analysis in Chinese organizations. Management and Organization Review, 1(3), 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R., Thomas, G., Legood, A., & Russo, S. D. (2018). Leader-member exchange (LMX) differentiation and work outcomes: Conceptual clarification and critical review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q., Wu, T. J., Duan, W., & Li, S. (2025). Effects of employee–Artificial Intelligence (AI) collaboration on counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs): Leader emotional support as a moderator. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, J. S., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Why seeking help from teammates is a blessing and a curse: A theory of help seeking and individual creativity in team contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offermann, L. R., Kennedy, K., & Wirtz, P. W. (1994). Implicit leadership theories: Content, structure, and generalizability. Leadership Quarterly, 5(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollier-Malaterre, A., Rothbard, N. P., & Berg, J. M. (2013). When worlds collide in cyberspace: How boundary work in online social networks impacts professional relationships. Academy of Management Review, 38(4), 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W., & Sun, L. Y. (2023). Do victims really help their abusive supervisors? Reevaluating the positive consequences of abusive supervision. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluut, H., Ilies, R., Curşeu, P. L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social support at work and at home: Dual-buffering effects in the work-family conflict process. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J., Kesebir, S., Günaydin, G., Selçuk, E., & Wasti, S. A. (2022). Gender differences in interpersonal trust: Disclosure behavior, benevolence sensitivity and workplace implications. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 169, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, B. S., & Porter, C. O. (2017). Are there advantages to seeing leadership the same? A test of the mediating effects of LMX on the relationship between ILT congruence and employees’ development. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(2), 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K., Lin, K. J., Lam, C. K., & Liu, W. (2023). Biting the hand that feeds: A status-based model of when and why receiving help motivates social undermining. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Stafford, K. (2020). Social support and turnover among entry-level service employees: Differentiating type, source, and basis of attachment. Human Resource Management, 59(3), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M., Carsten, M., & Huang, L. (2022). What do managers value in the leader-member exchange (LMX) relationship? Identification and measurement of the manager’s perspective of LMX (MLMX). Journal of Business Research, 148, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, B., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2005). Leader self-sacrifice and leadership effectiveness: The moderating role of leader prototypicality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Fan, X., Liu, J., Wu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Does a help giver seek the help from others? The consistency and licensing mechanisms and the role of leader respect. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(3), 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A., Michels, C., Burgmer, P., Mussweiler, T., Ockenfels, A., & Hofmann, W. (2021). Trust in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, L., Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2016). Pluralized leadership in complex organizations: Exploring the cross network effects between formal and informal leadership relations. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(2), 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., Zhao, B., & Yin, K. (2024). The double-edged sword of error sharing in organizations: From a self-disclosure perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 61(7), 3108–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theoretical Development | Representative Studies | Core Points |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction of ILT | Eden and Leviatan (1975) | Implicit leadership theory refers to subordinates’ beliefs about the qualities and abilities leaders should possess. |

| Cognitive structure elaboration | Lord et al. (1982) | Individuals typically hold prototypes of leadership; leader effectiveness may depend on the extent to which leaders meet these expectations. |

| Offermann et al. (1994) | Identified eight common implicit leadership traits: sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength. | |

| Epitropaki and Martin (2004) | Differentiated between leader prototypes (e.g., sensitivity, intelligence, dedication, dynamism) and anti-prototypes (e.g., tyranny, masculinity). | |

| Ling et al. (2000) | Proposed Chinese-specific leadership prototypes: moral, capability, relational, and participative leadership. | |

| Bidirectional interaction and contextual exploration | Riggs and Porter (2017) | Emphasized cognitive interactions between leaders and followers, suggesting that leaders need to adjust behaviors to align with followers’ expectations. |

| Gerpott et al. (2019); Heimann et al. (2020) | Followers hold both task-oriented and relation-oriented expectations of leaders. |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ESS | 0.364 | 0.299 | |||||||||

| 2. LMX | 0.805 | 0.224 | 0.221 ** | ||||||||

| 3. LI | 0.635 | 0.301 | 0.217 ** | 0.446 ** | |||||||

| 4. MC | 5.824 | 0.672 | 0.058 | 0.013 | −0.047 | ||||||

| 5. Term | 4.273 | 1.236 | −0.162 * | −0.002 | −0.028 | 0.039 | |||||

| 6. Gen | 1.287 | 0.454 | 0.128 | −0.112 | −0.036 | −0.001 | −0.069 | ||||

| 7. Age | 3.027 | 0.835 | 0.074 | 0.048 | −0.079 | 0.291 ** | 0.207 * | −0.073 | |||

| 8. Edu | 2.987 | 0.768 | 0.054 | −0.047 | 0.149 | −0.109 | −0.024 | 0.011 | −0.156 | ||

| 9. ESG | 0.412 | 0.269 | 0.320 ** | 0.155 | 0.249 ** | −0.016 | 0.036 | 0.068 | 0.040 | 0.094 | |

| 10. avGen | 0.463 | 0.311 | 0.320 *** | 0.155 | 0.249 | −0.016 | 0.036 | 0.068 | 0.040 | 0.094 | −0.194 * |

| LI | LMX | LI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Cons | 0.506 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.847 *** | 0.896 *** | −0.004 | 0.000 | 0.517 | 0.447 ** |

| (0.174) | (0.173) | (0.132) | (0.132) | (0.178) | (0.178) | (0.168) | (0.154) | |

| Term | −0.005 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.006 |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.018) | |

| Gen | −0.065 | −0.078 | −0.070 | −0.071 + | −0.031 | −0.039 | −0.081 | −0.044 |

| (0.055) | (0.054) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.049) | (0.050) | (0.052) | (0.048) | |

| Age | −0.027 | −0.034 | 0.001 | 0.006 | −0.031 | −0.035 | −0.022 | −0.017 |

| (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.030) | (0.027) | |

| Edu | 0.039 | 0.036 | −0.019 | −0.020 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.033 | 0.050 |

| (0.032) | (0.031) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.028) | |

| ESG | 0.312 *** | 0.253 ** | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.233 ** | 0.206 * | 0.276 ** | 0.222 ** |

| (0.081) | (0.095) | (0.072) | (0.072) | (0.083) | (0.086) | (0.092) | (0.084) | |

| avGen | 0.146 + | 0.156 | −0.009 | 0.001 | 0.156 * | 0.161 * | 0.177 * | 0.184 * |

| (0.081) | (0.080) | (0.061) | (0.061) | (0.073) | (0.073) | (0.078) | (0.071) | |

| ESS | 0.178 * | 0.158 * | 0.047 * | 0.090 | 0.046 + | 0.018 | ||

| (0.086) | (0.066) | (0.019) | (0.079) | (0.025) | (0.023) | |||

| LMX | 0.583 *** | 0.561 *** | 0.111 *** | |||||

| (0.098) | (0.100) | (0.022) | ||||||

| MC | −0.004 | −0.013 | −0.017 | |||||

| (0.019) | (0.024) | (0.023) | ||||||

| ESS × MC | −0.036 * | −0.077 *** | −0.047 * | |||||

| (0.017) | (0.020) | (0.021) | ||||||

| LMX × MC | - | −0.037 + | ||||||

| (0.020) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.107 | 0.134 | 0.082 | 0.110 | 0.286 | 0.292 | 0.203 | 0.348 |

| △R2 | 0.107 | 0.027 | 0.082 | 0.028 | 0.179 | 0.006 | 0.069 | 0.145 |

| F | 2.863 * | 3.129 ** | 1.882 + | 1.931 + | 8.126 *** | 7.283 *** | 3.969 *** | 6.688 *** |

| Path | Estimate | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mediation effect (ESS-LMX-LI) | 0.089 | [0.005, 0.198] | |

| moderated mediation effect | +1 SD | −0.030 | [−0.080, 0.008] |

| −1 SD | 0.024 | [−0.021, 0.074] | |

| difference | −0.054 | [−0.127, −0.004] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Lv, H. The Strength of Vulnerability: How Does Supervisors’ Emotional Support-Seeking Promote Leadership Influence? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101326

Wu H, Lv H. The Strength of Vulnerability: How Does Supervisors’ Emotional Support-Seeking Promote Leadership Influence? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101326

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Haoyu, and Hongjiang Lv. 2025. "The Strength of Vulnerability: How Does Supervisors’ Emotional Support-Seeking Promote Leadership Influence?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101326

APA StyleWu, H., & Lv, H. (2025). The Strength of Vulnerability: How Does Supervisors’ Emotional Support-Seeking Promote Leadership Influence? Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101326