Financial Status of Model, Target, and Observer Modulates Mate Choice Copying and the Mediating Effect of Personality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Background

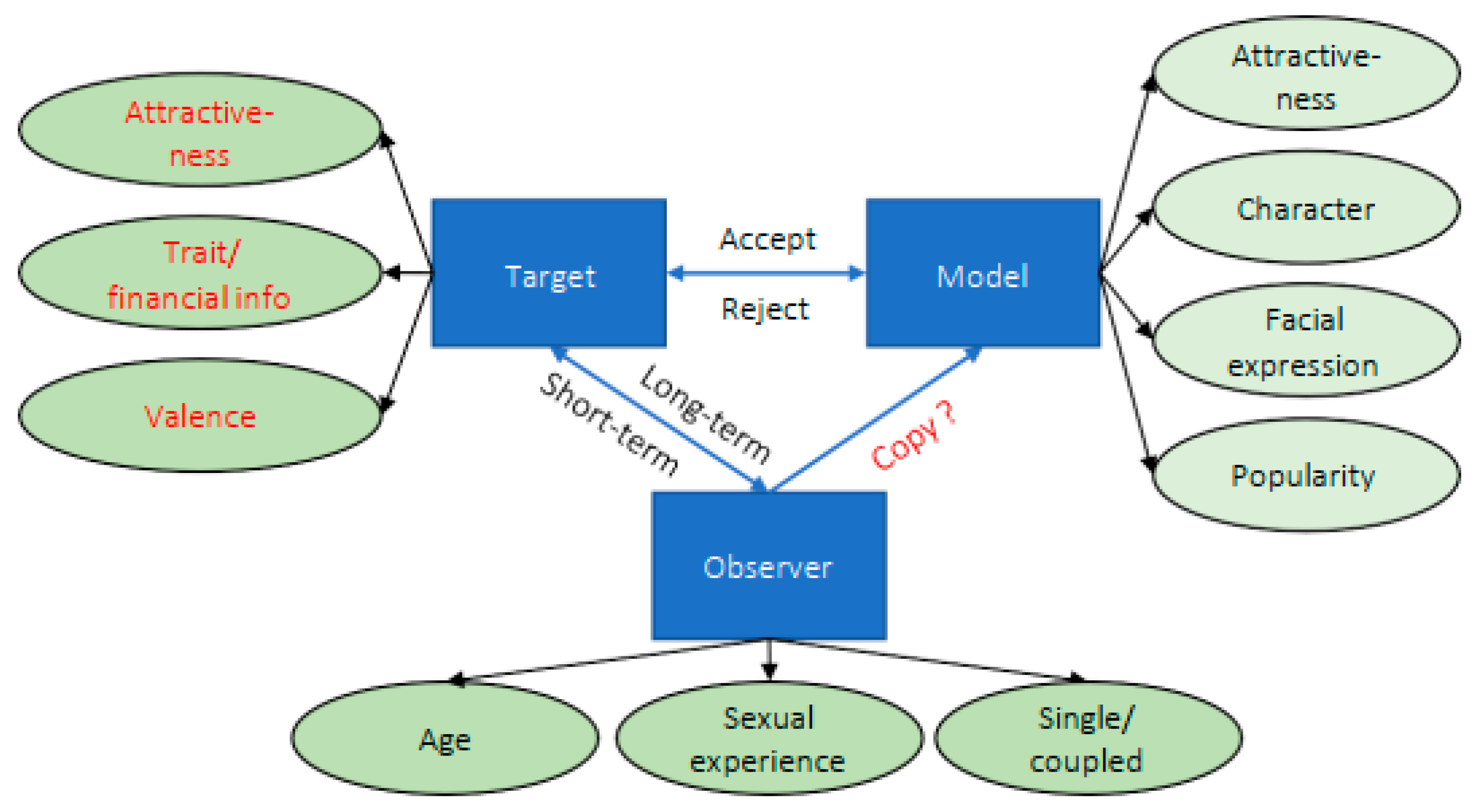

1.2. Mate Choice Copying

2. The Present Study

3. Experiment 1: Model’s Financial Status Affects Mate Choice Copying

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials

Headshots

College Students’ Subjective Social Status Scale

3.1.3. Design

3.1.4. Procedure

3.2. Results and Discussion

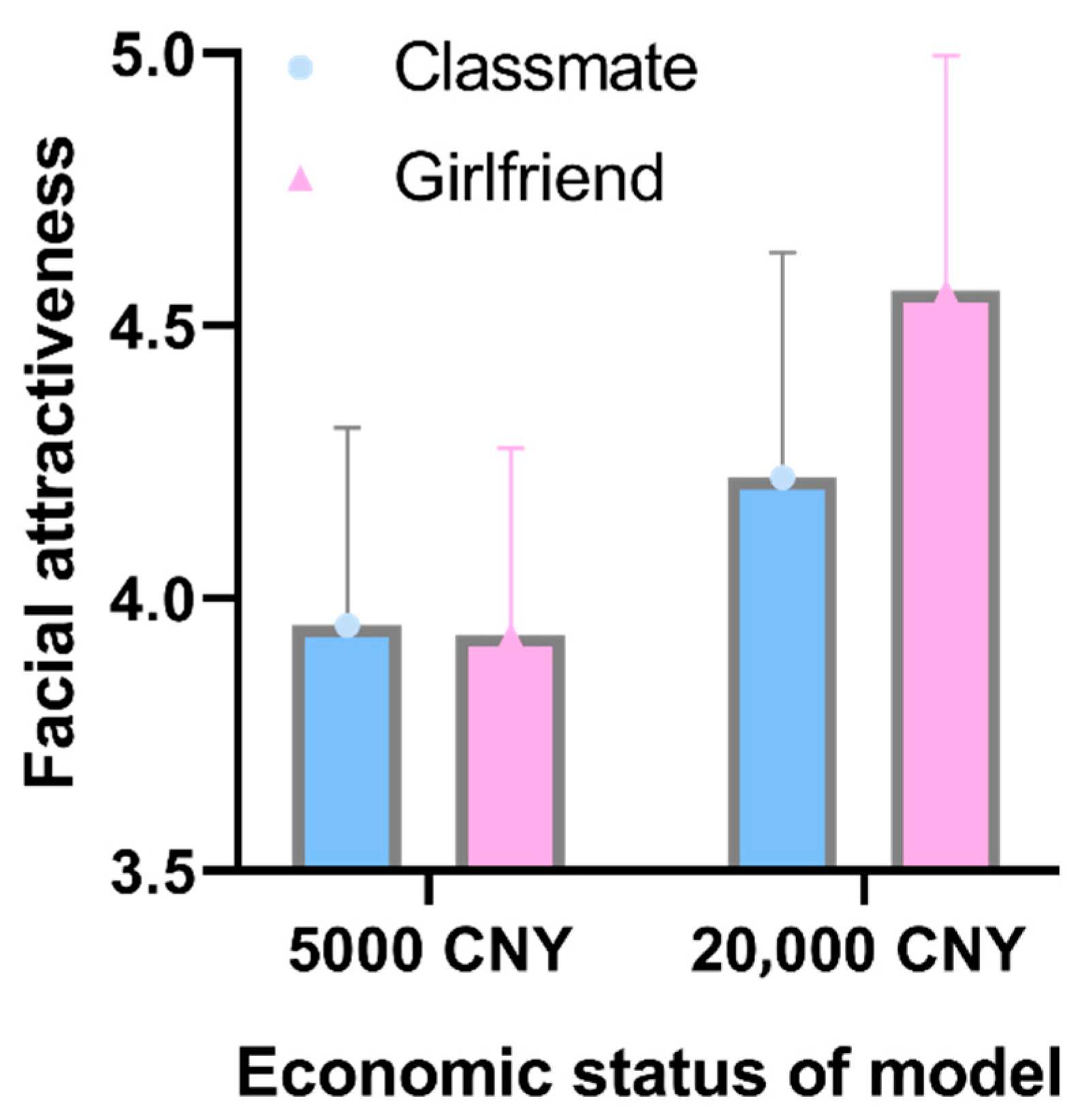

3.2.1. Facial Attractiveness Rating

3.2.2. Mediating Effect of Perceived Personality

3.2.3. Subjective Social Status

4. Experiment 2: Financial Status of the Target Modulates the Impact of the Financial Status of the Model on Mate Choice Copying

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Design

4.1.3. Materials

4.1.4. Procedure

4.2. Results and Discussion

4.2.1. Manipulation Check on Observer’s Financial Status

4.2.2. Facial Attractiveness Rating

4.2.3. Mediating Effect of Perceived Personality

5. Experiment 3: Observer Financial Status Modulates the Impact of Model Financial Status on Mate Choice Copying

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants

5.1.2. Design

5.1.3. Procedure

5.2. Results and Discussion

5.2.1. Facial Attractiveness Rating

5.2.2. Rating of Financial Status, Social Status, Personality, and Intelligence

5.2.3. Mediating Effect of Financial Status, Social Status, Personality, and Intelligence

6. General Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Model Financial Status as a Key Factor in Mate Choice Copying

6.2. Target Financial Status Modulates Model’s Influence on Mate Choice Copying

6.3. Observer Financial Status Modulates Model’s Influence on Mate Choice Copying

6.4. Different Social Learning Mechanisms Across Observers of Different Financial Statuses

6.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Anderson, R. C., & Surbey, M. K. (2020). Human mate copying as a form of nonindependent mate selection: Findings and considerations. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOSS Direct Recruitment. (2019, September). 2019 job search trend report for fresh graduates. Available online: https://news.cyol.com/co/2019-09/19/content_18162429.htm (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Bowers, R. I., Place, S. S., Todd, P. M., Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2012). Generalization in mate choice copying in humans. Behavioral Ecology, 23(1), 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(3), 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emotional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(1), 147470490800600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G., Chen, Y., Guan, Y., & Zhang, D. (2015). On composition of college students’ subjective social status indexes and their characteristics. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition), 6, 156–162. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S. (2012). I like who you like, but only if I like you: Female character affects mate choice copying. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(6), 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy-Beam, D., Walter, K. V., & Duarte, K. (2022). What is a mate preference? Probing the computational format of mate preferences using couple simulation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(6), 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M. E., & Ramsey, M. E. (2015). Mate choice as social cognition: Predicting female behavioral and neural plasticity as a function of alternative male reproductive tactics. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 6, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54(6), 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, A. (1992). Gender differences in mate selection preferences: A test of the parental investment model. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, M., & Morgan, T. J. H. (2023). Prestige, conformity and gender consistency support a broad-context mechanism underpinning mate choice copying. Evolution and Human Behavior, 45(1), 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda-Vossos, A., Brooks, R. C., & Dixson, B. J. W. (2019). The interplay between economic status and attractiveness, and the importance of attire in mate choice judgments. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda-Vossos, A., Nakagawa, S., Dixson, B. J., & Brooks, R. C. (2018). Mate choice copying in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 4(4), 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. E., & Buss, D. M. (2008). The mere presence of opposite-sex others on judgments of sexual and romantic desirability: Opposite effects for men and women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(5), 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavaliers, M., Matta, R., & Choleris, E. (2017). Mate choice copying, social information processing, and the roles of oxytocin. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 72, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendal, R. L., Boogert, N. J., Rendell, L., Laland, K. N., Webster, M., & Jones, P. L. (2018). Social learning strategies: Bridge-building between fields. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(7), 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N. P., Yong, J. C., Tov, W., Sng, O., Fletcher, G. J., Valentine, K. A., Jiang, Y. F., & Balliet, D. (2013). Mate preferences do predict attraction and choices in the early stages of mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(5), 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A. C., Caldwell, C. A., Jones, B. C., & DeBruine, L. M. (2015). Observer age and the social transmission of attractiveness in humans: Younger women are more influenced by the choices of popular others than older women. British Journal of Psychology, 106(3), 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., & Caldwell, C. A. (2011). Social learning and human mate preferences: A potential mechanism for generating and maintaining between-population diversity in attraction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1563), 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Zhang, C., Wang, X., Feng, X., Pan, J., & Zhou, G. (2021). Trait/financial information of potential male mate eliminates mate choice copying by women: Trade-off between social information and personal information in mate selection. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(8), 3757–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. J., Zhu, X. Q., & Chang, L. (2015). Good genes, good providers, and good fathers: Economic development involved in how women select a mate. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S. S., Todd, P. M., Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2010). Humans show mate copying after observing real mate choices. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokosch, M. D., Coss, R. G., Scheib, J. E., & Blozis, S. A. (2009). Intelligence and mate choice: Intelligent men are always appealing. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeheffer, C. D., Proffitt Leyva, R. P., & Hill, S. E. (2016). Attractive female romantic partners provide a proxy for unobservable male qualities: The when and why behind human female mate choice copying. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(2), 1474704916652144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, G. G., & Ryan, M. J. (2022). Sexual selection and the ascent of women: Mate choice research since Darwin. Science, 375(6578), eabi6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J. E., Kostic, B., & Buchanan, E. M. (2020). How the presence of others affects desirability judgments in heterosexual and homosexual participants. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, S. E., Morgan, T. J. H., Thornton, A., Brown, G. R., Laland, K. N., & Cross, C. P. (2018). Human mate choice copying is domain-general social learning. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q., Zhang, L., & Sun, S. (2019). The impact of economic status on female mating preferences from the perspective of evolutionary psychology. Psychological Science, 42(3), 681–687. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection & the descent of man (pp. 136–179). Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara, T., Yokomizo, H., & Iwasa, Y. (2005). Mate-choice copying as bayesian decision making. The American Naturalist, 165(3), 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uller, T., & Johansson, L. C. (2003). Human mate choice and the wedding ring effect. Human Nature, 14(3), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Zhou, S., Kong, X., Han, D., Liu, Y., Sun, L., Mao, W., Maguire, P., & Hu, Y. (2021). The influence of model quality on self-other mate choice copying. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, J. (2016). PANGEA: Power analysis for general ANOVA designs. Available online: http://jakewestfall.org/publications/pangea.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- White, D. J., & Galef, B. G., Jr. (2000). Differences between the sexes in direction and duration of response to seeing a potential sex partner mate with another. Animal Behaviour, 59(6), 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wiederman, M. W., & Allgeier, E. R. (1992). Gender differences in mate selection criteria: Sociobiological or socioeconomic explanation? Ethology and Sociobiology, 13(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J., Xu, J., Zhang, S., & Yu, F. (2012). Mate copying: An adaptive sexual selection strategy. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(10), 1672–1678. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Financial Status Model | High Financial Status Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Effect | SE | Statistics | p | Effect | SE | Statistics | p |

| Total | −0.018 | 0.051 | t = −0.342 | 0.735 | 0.343 | 0.076 | t = 4.522 | <0.001 |

| Direct effect | −0.044 | 0.048 | t = −0.901 | 0.374 | 0.213 | 0.073 | t = 2.916 | 0.006 |

| Indirect effect | 0.026 | 0.023 | Z = 1.121 | 0.262 | 0.130 | 0.054 | Z = 2.418 | 0.016 |

| Effect | F | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship (R) | 0.047 | 1.47 | 0.829 | 0.001 |

| Model financial status (M) | 3.975 | 1.47 | 0.052 | 0.078 |

| Target financial status (T) | 111.917 | 1.47 | 0.000 | 0.704 |

| R × M | 8.036 | 1.47 | 0.007 | 0.146 |

| R × T | 8.343 | 1.47 | 0.006 | 0.151 |

| M × T | 2.966 | 1.47 | 0.092 | 0.059 |

| R × M × T | 11.386 | 1.47 | 0.001 | 0.195 |

| Financial Status | Relationship | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Target | Girlfriend | Classmates | ||

| Low | Low | 3.68 | 3.78 | 3.56 | 0.065 |

| High | Low | 3.72 | 3.45 | 11.51 | 0.001 |

| Low | High | 4.61 | 4.65 | 0.68 | 0.413 |

| High | High | 4.55 | 4.65 | 2.86 | 0.098 |

| Low Financial Status Model | High Financial Status Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Effect | SE | Statistics | p | Effect | SE | Statistics | p |

| Low financial status target | ||||||||

| Total | −0.096 | 0.051 | t = −1.888 | 0.065 | 0.263 | 0.077 | t = 3.392 | 0.001 |

| Direct | −0.056 | 0.043 | t = −1.283 | 0.206 | 0.098 | 0.052 | t = 1.904 | 0.063 |

| Indirect | −0.040 | 0.030 | Z = −1.348 | 0.178 | 0.165 | 0.064 | Z = 2.571 | 0.010 |

| High financial status target | ||||||||

| Total | −0.039 | 0.047 | t = −0.826 | 0.413 | −0.098 | 0.058 | t = −1.690 | 0.098 |

| Direct | −0.015 | 0.042 | t = −0.346 | 0.731 | −0.025 | 0.047 | t = −0.539 | 0.592 |

| Indirect | −0.024 | 0.024 | Z = −1.035 | 0.301 | −0.072 | 0.039 | Z = −1.859 | 0.063 |

| MSE | F | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship (R) | Attractiveness | 8.555 | 29.401 | 0.000 | 0.250 |

| Financial status | 16.369 | 29.084 | 0.000 | 0.248 | |

| Social status | 15.387 | 27.415 | 0.000 | 0.238 | |

| Personality quality | 13.609 | 25.032 | 0.000 | 0.221 | |

| Intelligence | 13.390 | 25.364 | 0.000 | 0.224 | |

| Model financial status (M) | Attractiveness | 37.629 | 59.564 | 0.000 | 0.404 |

| Financial status | 148.727 | 150.627 | 0.000 | 0.631 | |

| Social status | 128.880 | 140.151 | 0.000 | 0.614 | |

| Personality quality | 61.410 | 83.461 | 0.000 | 0.487 | |

| Intelligence | 106.383 | 122.400 | 0.000 | 0.582 | |

| Observer’s financial status (O) | Attractiveness | 5.866 | 0.912 | 0.406 | 0.020 |

| Financial status | 62.050 | 12.193 | 0.000 | 0.217 | |

| Social status | 47.416 | 9.173 | 0.000 | 0.173 | |

| Personality quality | 83.349 | 13.263 | 0.000 | 0.232 | |

| Intelligence | 63.868 | 10.632 | 0.000 | 0.195 | |

| R × M | Attractiveness | 1.141 | 15.099 | 0.000 | 0.146 |

| Financial status | 9.130 | 34.865 | 0.000 | 0.284 | |

| Social status | 10.217 | 38.176 | 0.000 | 0.303 | |

| Personality quality | 4.047 | 23.896 | 0.000 | 0.214 | |

| Intelligence | 7.596 | 29.573 | 0.000 | 0.252 | |

| R × O | Attractiveness | 0.943 | 3.240 | 0.044 | 0.069 |

| Financial status | 1.257 | 2.234 | 0.113 | 0.048 | |

| Social status | 1.622 | 2.890 | 0.061 | 0.062 | |

| Personality quality | 1.086 | 1.997 | 0.142 | 0.043 | |

| Intelligence | 1.632 | 3.092 | 0.050 | 0.066 | |

| M × O | Attractiveness | 0.852 | 1.349 | 0.265 | 0.030 |

| Financial status | 0.891 | 0.902 | 0.409 | 0.020 | |

| Social status | 1.238 | 1.346 | 0.266 | 0.030 | |

| Personality quality | 2.193 | 2.981 | 0.056 | 0.063 | |

| Intelligence | 1.105 | 1.271 | 0.286 | 0.028 | |

| R × M × O | Attractiveness | 0.542 | 7.168 | 0.001 | 0.140 |

| Financial status | 0.226 | 0.863 | 0.426 | 0.019 | |

| Social status | 0.096 | 0.360 | 0.699 | 0.008 | |

| Personality quality | 0.129 | 0.759 | 0.471 | 0.017 | |

| Intelligence | 0.296 | 1.152 | 0.321 | 0.026 |

| Observer’s Financial Status | Low Financial Status Model | High Financial Status Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girlfriend | Classmate | p | Girlfriend | Classmate | p | |

| Low | 3.469 (0.180) | 3.364 (0.19) | 0.098 | 3.968 (0.188) | 3.784 (0.212) | 0.028 |

| Medium | 3.052 (0.260) | 2.588 (0.167) | 0.011 | 3.868 (0.378) | 3.344 (0.302) | <0.001 |

| High | 3.042 (0.235) | 3.026 (0.226) | 0.848 | 3.992 (0.302) | 3.444 (0.258) | <0.001 |

| Effect | Low Financial Status Observer | Medium Financial Status Observer | High Financial Status Observer | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Statistics | p | Effect | SE | Statistics | p | Effect | SE | Statistics | p | |

| Financial status | ||||||||||||

| Total | 0.144 | 0.058 | t = 2.498 | 0.018 | 0.494 | 0.134 | t = 3.695 | 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.090 | t = 3.150 | 0.004 |

| Direct | 0.045 | 0.048 | t = 0.936 | 0.357 | 0.141 | 0.112 | t = 1.262 | 0.218 | 0.029 | 0.046 | t = 0.639 | 0.528 |

| Indirect | 0.099 | 0.044 | Z = 2.267 | 0.023 | 0.353 | 0.116 | Z = 3.046 | 0.002 | 0.253 | 0.084 | Z = 3.014 | 0.003 |

| Social status | ||||||||||||

| Total | 0.144 | 0.058 | t = 2.498 | 0.018 | 0.494 | 0.134 | t = 3.695 | 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.090 | t = 3.150 | 0.004 |

| Direct | 0.041 | 0.044 | t = 0.928 | 0.361 | 0.148 | 0.100 | t = 1.489 | 0.148 | 0.076 | 0.034 | t = 2.221 | 0.035 |

| Indirect | 0.104 | 0.046 | Z = 2.256 | 0.024 | 0.336 | 0.117 | Z = 2.961 | 0.003 | 0.206 | 0.085 | Z = 3.046 | 0.016 |

| Personality | ||||||||||||

| Total | 0.144 | 0.058 | t = 2.498 | 0.018 | 0.494 | 0.134 | t = 3.695 | 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.090 | t = 3.150 | 0.004 |

| Direct | 0.049 | 0.046 | t = 1.056 | 0.300 | 0.145 | 0.110 | t = 1.316 | 0.199 | 0.045 | 0.048 | t = 0.933 | 0.359 |

| Indirect | 0.095 | 0.044 | Z = 2.168 | 0.030 | 0.349 | 0.116 | Z = 3.019 | 0.003 | 0.237 | 0.083 | Z = 2.865 | 0.004 |

| Intelligence | ||||||||||||

| Total | 0.144 | 0.058 | t = 2.498 | 0.018 | 0.494 | 0.134 | t = 3.695 | 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.090 | t = 3.150 | 0.004 |

| Direct | 0.076 | 0.044 | t = 1.754 | 0.090 | 0.188 | 0.060 | t = 3.148 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.047 | t = 0.409 | 0.686 |

| Indirect | 0.068 | 0.043 | Z = 1.592 | 0.111 | 0.228 | 0.050 | Z = 4.594 | <0.001 | 0.263 | 0.084 | Z = 3.129 | 0.002 |

| Effect | Low Financial Status Model | High Financial Status Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Statistics | p | Effect | SE | Statistics | p | |

| Financial status | ||||||||

| Total | 0.194 | 0.068 | t = 2.845 | 0.006 | 0.416 | 0.063 | t = 6.605 | <0.001 |

| Direct | 0.111 | 0.036 | t = 3.112 | 0.003 | 0.158 | 0.060 | t = 2.634 | 0.010 |

| Indirect | 0.082 | 0.059 | Z = 1.406 | 0.160 | 0.258 | 0.052 | Z = 4.952 | <0.001 |

| Social status | ||||||||

| Total | 0.194 | 0.068 | t = 2.845 | 0.006 | 0.416 | 0.063 | t = 6.605 | <0.001 |

| Direct | 0.137 | 0.037 | t = 3.731 | <0.001 | 0.154 | 0.059 | t = 2.591 | 0.011 |

| Indirect | 0.057 | 0.058 | Z = 0.989 | 0.323 | 0.262 | 0.052 | Z = 5.005 | <0.001 |

| Personality | ||||||||

| Total | 0.194 | 0.068 | t = 2.845 | 0.006 | 0.416 | 0.063 | t = 6.605 | <0.001 |

| Direct | 0.055 | 0.035 | t = 1.569 | 0.120 | 0.192 | 0.060 | t = 3.250 | 0.002 |

| Indirect | 0.139 | 0.060 | Z = 2.326 | 0.020 | 0.225 | 0.049 | Z = 4.552 | <0.001 |

| Intelligence | ||||||||

| Total | 0.194 | 0.068 | t = 2.845 | 0.006 | 0.416 | 0.063 | t = 6.605 | <0.001 |

| Direct | 0.120 | 0.037 | t = 3.273 | 0.002 | 0.188 | 0.060 | t = 3.148 | 0.002 |

| Indirect | 0.074 | 0.058 | Z = 1.274 | 0.203 | 0.228 | 0.050 | Z = 4.594 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, G.; Ma, S.; Wu, D. Financial Status of Model, Target, and Observer Modulates Mate Choice Copying and the Mediating Effect of Personality. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101324

Zhou G, Ma S, Wu D. Financial Status of Model, Target, and Observer Modulates Mate Choice Copying and the Mediating Effect of Personality. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101324

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Guomei, Shaxiao Ma, and Di Wu. 2025. "Financial Status of Model, Target, and Observer Modulates Mate Choice Copying and the Mediating Effect of Personality" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101324

APA StyleZhou, G., Ma, S., & Wu, D. (2025). Financial Status of Model, Target, and Observer Modulates Mate Choice Copying and the Mediating Effect of Personality. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101324