Triggering the Personalization Backfire Effect: The Moderating Role of Situational Privacy Concern

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Evolution of Personalized Marketing

2.2. The Double-Edge of Personalized Marketing

2.3. The Role and Sensitivity of Personal Information

2.4. Situational Privacy Concern as a Key Moderator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants and Procedure

3.3. Experimental Stimuli and Manipulations

3.4. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Stimuli

Appendix A.1. Situational Privacy Concern Primes (News Articles)

Mr./Ms. A, an office worker in their 20s, recently searched Google twice for flight ticket prices for a trip to Thailand. To decide on a destination, they also searched for ‘#Bangkok’ on Instagram. Afterward, strangely enough, even when accessing work-related websites on Google, ads for Thailand flights from other airlines would appear, and on Instagram, an ad from a travel agency for a “7-night Thailand package tour for those in their 20s” popped up. Despite having searched only a few times, Google and Instagram seemed to know Mr./Ms. A all too well. The Personal Information Protection Commission has imposed a fine of approximately 100 billion won on Google and Meta (formerly Facebook) for violating the Personal Information Protection Act, the largest fine ever for such a violation. It was confirmed that the two companies had been collecting personal information for years without user consent to use for online personalized advertising.[22 September 2022, Newspaper A]

Samsung Electronics has experienced a customer data leak. According to a notice Samsung Electronics issued to its U.S. customers, in late July, an unauthorized third party breached some of Samsung’s U.S. systems and extracted information. In August, the company confirmed that the personal information of certain customers had been affected and issued the notice. According to Samsung Electronics’ announcement on the 2nd (U.S. local time), it is presumed that names, contact information, dates of birth, and product registration information were leaked.[5 September 2022, Newspaper B]

As more consumers seek to decorate their spaces into comfortable sanctuaries, ‘Healing Minimalism’ is emerging as a new fall interior trend. Minimalism is an artistic and cultural movement that pursues simplicity and conciseness, and the formula for healing minimalism lies in this simplicity. It was recently emphasized that, “The mattress, which is responsible for the beginning and end of our day, is the piece of furniture that takes care of a modern person’s healing.” The article stressed, “Mattresses with simple designs equipped with functions faithful to the basics of sleep will provide consumers with a comfortable sanctuary.”[7 October 2022, Newspaper A]

Within the “selective premium” trend, beds and sofas have become increasingly important items. This is because they not only support the body when lying or sitting down but also visually dictate the atmosphere of key spaces like the bedroom and living room. Various new products are being launched that capture the essence of autumn in interior furniture. In particular, they are elevating consumers’ interest and sense of interior design by using color palettes that match the fall and promote comfort.[19 September 2022, Newspaper B]

Appendix A.2. Message Personalization Stimuli (Marketing Messages)

| Personalization | Message Text |

| High | Hello, Mr./Ms. Kim Jung-ang. I see you’re near the Homeplus Sindorim branch, which you visited last week. We’re offering you a coupon for up to 20% off, based on the 100,000 won you recently spent at Homeplus! A fresh and delicious experience every day! Enjoy it at Homeplus. |

| Medium | Hello, customer. We’re offering a coupon for up to 20% off at Homeplus stores within 1km of your current location! A fresh and delicious experience every day! Enjoy it at Homeplus. |

| Low | Hello, customer. We’re offering a coupon for you to receive up to 20% off at Homeplus! A fresh and delicious experience every day! Enjoy it at Homeplus. |

References

- An, G. K., & Ngo, T. T. A. (2025). AI-powered personalized advertising and purchase intention in Vietnam’s digital landscape: The role of trust, relevance, and usefulness. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11(3), 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T. H., & Morimoto, M. (2012). Stay Away From Me: Examining the Determinants of Consumer Avoidance to Personalized Advertising. Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, E. D., & Munuera-Alemán, J. L. (2001). Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11), 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A., & Eisenbeiss, M. (2015). Personalized online advertising effectiveness: The interplay of what, when, and where. Marketing Science, 34(5), 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S. C., Kruikemeier, S., & Bol, N. (2021). When is personalized advertising crossing personal boundaries? How type of information, data sharing, and personalized pricing influence consumer perceptions of personalized advertising. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic. [Google Scholar]

- De Keyzer, F., Buzeta, C., & Lopes, A. I. (2024). The role of well-being in consumer’s responses to personalized advertising on social media. Psychology & Marketing, 41(6), 1206–1222. [Google Scholar]

- De Keyzer, F., Van Noort, G., & Kruikemeier, S. (2022). Going too far? How consumers respond to personalized advertising from different sources. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 23(3), 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dinev, T., & Hart, P. (2006). An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Information Systems Research, 17(1), 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S., & Jordaan, Y. (2007). A market-oriented approach to responsibly managing information privacy concerns in direct marketing. Journal of advertising, 36(2), 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, E., Eriksson, K., Björnstjerna, M., & Strimling, P. (2023). Global variations in online privacy concerns across 57 countries. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 9, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, L 119, 1–88. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Federal Trade Commission. (2012, March). Protecting consumer privacy in an era of rapid change: Recommendations for businesses and policymakers. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-report-protecting-consumer-privacy-era-rapid-change-recommendations/120326privacyreport.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Frank, T. B., Felix, E., Peter, C. V., & Jaap, E. W. (2022). Consumers’ privacy calculus: The PRICAL index development and validation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(1), 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, A., Rocher, L., Houssiau, F., Creţu, A. M., & De Montjoye, Y. A. (2024). Anonymization: The imperfect science of using data while preserving privacy. Science Advances, 10(29), eadn7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2004). Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega, 32(6), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyzer, D., Freya, D., Nathalie, & Pelsmacker, D. (2022). How and when personalized advertising leads to brand attitude, click, and WOM intention. Journal of Advertising, 51(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., Barasz, K., & Leslie, J. (2018). Why am i seeing this ad? The effect of Ad transparency on Ad effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(5), 906–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R., Tang, D., & Xu, Y. (2020). Trustworthy online controlled experiments: A practical guide to a/b testing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., Moon, W. K., & Song, Y. G. (2025). Is It transparent or surveillant? The effects of personalized advertising and privacy policy on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 25(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J. K., Kim, T., & Barasz, K. (2018). Ads that don’t overstep: How to make sure you don’t take personalization too far. Harvard Business Review, 95(4), 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., & Shi, J. (2025). Message effects on psychological reactance: Meta-analyses. Human Communication Research, hqaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Wang, H., & Zhu, Y. (2025). You plan to manipulate me: A persuasion knowledge perspective for understanding the effects of AI-assisted selling. Journal of Business Research, 200, 115598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K., Verleye, K., De Keyser, A., & Lariviere, B. (2024). The transformative potential of AI-enabled personalization across cultures. Journal of Services Marketing, 38(6), 711–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personal Information Protection Commission & Korea Internet & Security Agency. (2024). 2023 Survey on the state of personal information protection. Personal Information Protection Commission & Korea Internet & Security Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Segijn, C. M., Kim, E., & van Ooijen, I. (2024). The role of perceived surveillance and privacy cynicism in effects of multiple synced advertising exposures on brand attitude. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 45(4), 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. J., Milberg, S. J., & Burke, S. J. (1996). Information privacy: Measuring individuals’ concerns about organizational practices. MIS Quarterly, 20, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiekermann, S., Grossklags, J., & Berendt, B. (2001, October 14–17). E-privacy in 2nd generation e-commerce: Privacy preferences versus actual behavior. The 3rd ACM conference on Electronic Commerce (pp. 38–47), Tampa, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., Xie, P., & Sun, Y. (2025). The Inverted U-Shaped Effect of Personalization on Consumer Attitudes in AI-Generated Ads: Striking the Right Balance Between Utility and Threat. Journal of Advertising Research, 65(2), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S., Liu, Y., & Sun, C. (2024). Understanding information sensitivity perceptions and its impact on information privacy concerns in e-commerce services: Insights from China. Computers & Security, 138, 103646. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, C. E. (2014). Social networks, personalized advertising, and privacy controls. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(5), 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T. B., Debra, L. Z., Helge, T., & Sharon, S. (2008). Getting Too Personal: Reactance to Highly Personalized eMail Solicitations. Marketing Letters, 19(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Luo, X. R., Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (2011). The personalization privacy paradox: An exploratory study of decision making process for location-aware marketing. Decision Support Systems, 51(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, T. E. D., Chu, T. H., & Li, Q. (2025). How Persuasive Is Personalized Advertising? A Meta-Analytic Review of Experimental Evidence of the Effects of Personalization on Ad Effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YouGov. (2025). Ad-verse reactions: U.S. personalized advertising report 2025. Available online: https://commercial.yougov.com/rs/464-VHH-988/images/WP-2025-03-US-personalized-advertising-report.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

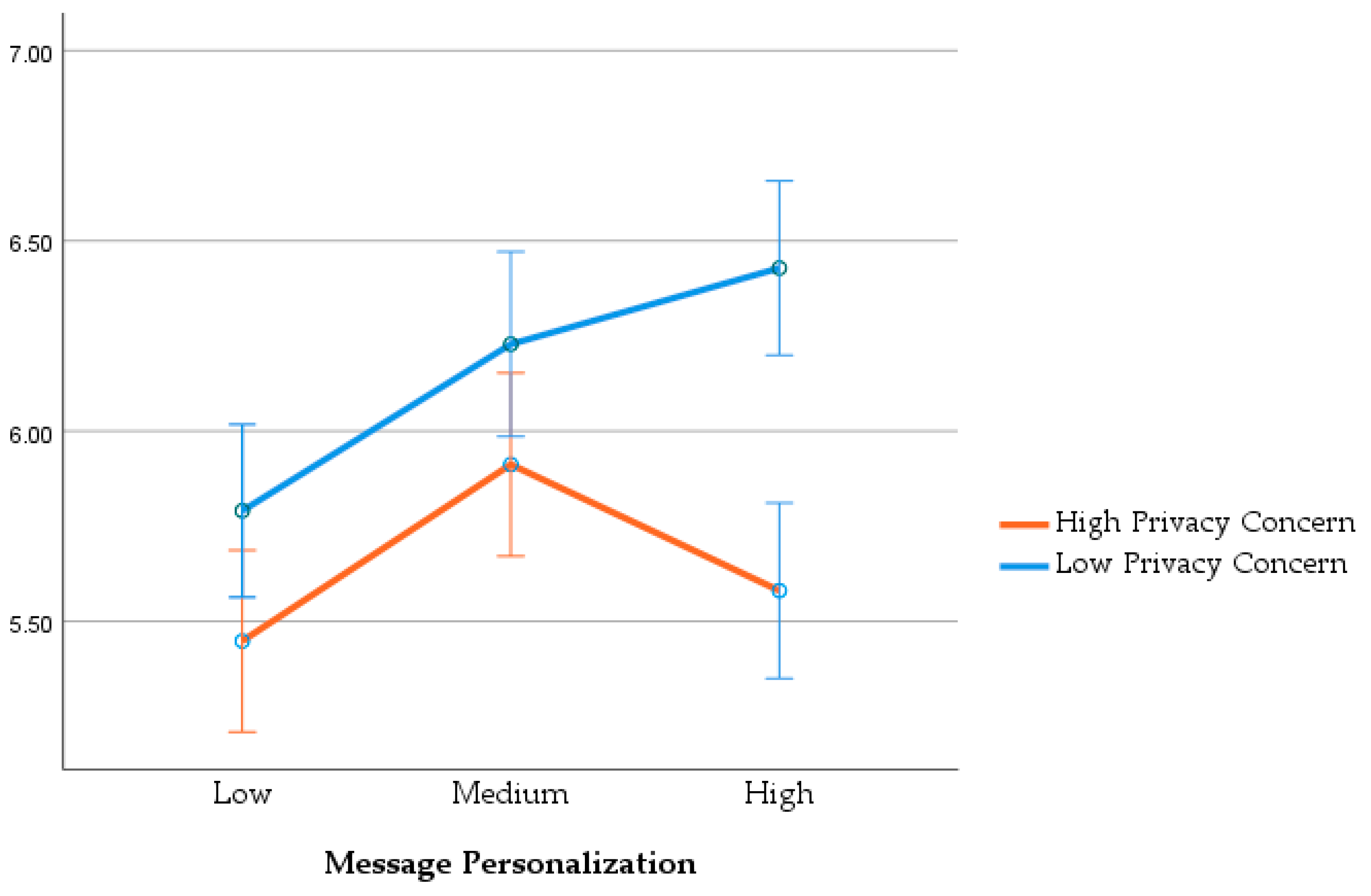

| Privacy Concern | Personalization | Mean | N | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | High | 5.58 | 62 | 0.90 |

| Medium | 5.91 | 57 | 0.97 | |

| Low | 5.45 | 58 | 0.95 | |

| Total | 5.64 | 177 | 0.95 | |

| Low | High | 6.43 | 63 | 0.83 |

| Medium | 6.23 | 56 | 0.91 | |

| Low | 5.79 | 64 | 0.98 | |

| Total | 6.14 | 183 | 0.94 | |

| Total | High | 6.01 | 125 | 0.96 |

| Medium | 6.07 | 113 | 0.95 | |

| Low | 5.63 | 122 | 0.98 | |

| Total | 5.90 | 360 | 0.98 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 42.58 | 5 | 8.52 | 9.97 | 0.000 | 0.12 |

| Intercept | 12,490.14 | 1 | 12,490.14 | 14,622.35 | 0.000 | 0.98 |

| Privacy Concern | 22.64 | 1 | 22.64 | 26.50 | 0.000 | 0.07 |

| Personalization | 14.22 | 2 | 7.11 | 8.32 | 0.000 | 0.04 |

| Privacy Concern * Personalization | 5.48 | 2 | 2.74 | 3.21 | 0.042 | 0.02 |

| Error | 302.38 | 354 | 0.85 | |||

| Total | 12,869.48 | 360 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 344.96 | 359 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Han, S. Triggering the Personalization Backfire Effect: The Moderating Role of Situational Privacy Concern. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101323

Kim H, Han S. Triggering the Personalization Backfire Effect: The Moderating Role of Situational Privacy Concern. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101323

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyeongseok, and Seunghee Han. 2025. "Triggering the Personalization Backfire Effect: The Moderating Role of Situational Privacy Concern" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101323

APA StyleKim, H., & Han, S. (2025). Triggering the Personalization Backfire Effect: The Moderating Role of Situational Privacy Concern. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101323