Moral Judgments Across the Economic Divide: The Effect of Perceived Economic Inequality and Status in Judgment of Transgressions, Justification, and Dehumanization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Economic Inequality and Moral Judgments

1.2. Socioeconomic Status and Moral Judgments

1.3. Judgment of the Transgression, Moral Justification, and Dehumanization

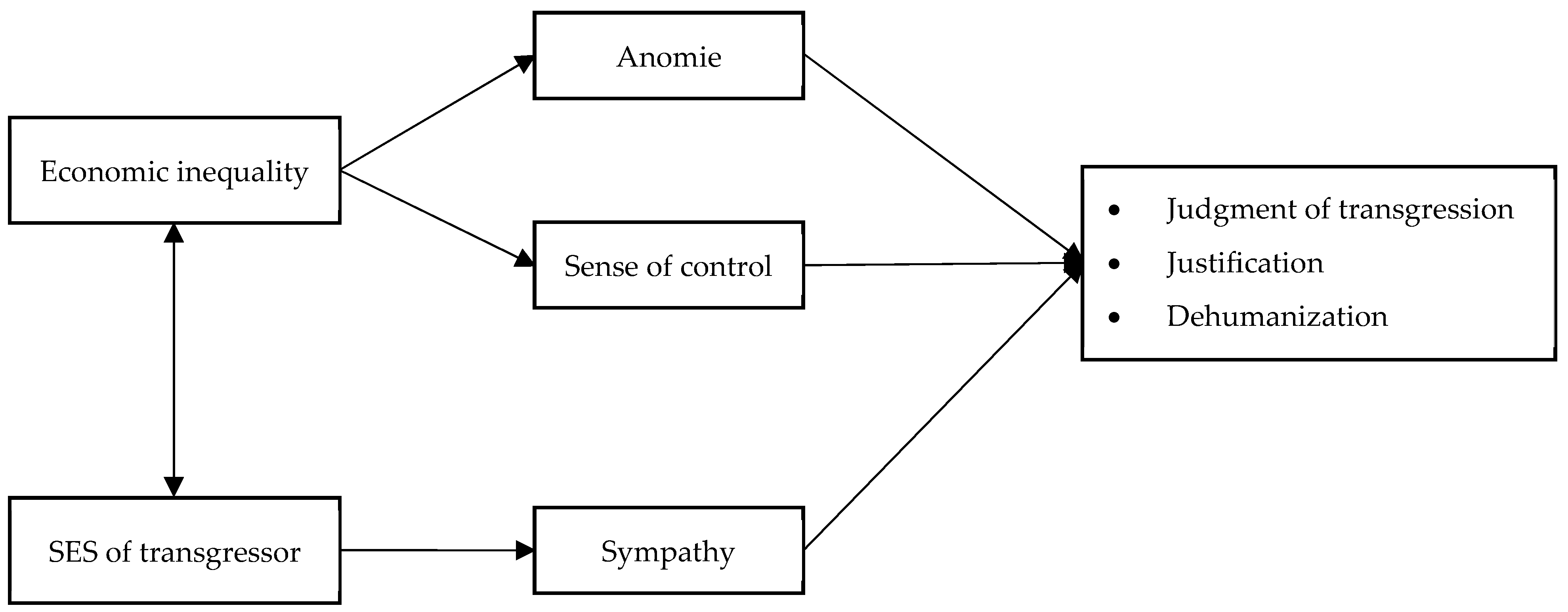

1.4. Overview of the Present Studies

2. Study 1

- H1: Transgressions committed by high-status individuals will be judged more harshly when committed in unequal societies than when committed in equal societies (H1.1). Conversely, transgressions committed by low-status individuals will be judged less harshly when committed in unequal societies than when committed in equal societies (H1.2).

- H2: Moral transgressions will be more justified when committed in unequal societies than in equal societies (H2.1) or by low-status individuals than by high-status individuals (H2.2).

- H3: High-status transgressors will be more dehumanized in unequal societies than in equal societies (H3.1), while low-status transgressors will be less dehumanized in unequal societies than in equal societies (H3.2).

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants and Design

2.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Manipulation of Economic Inequality

Manipulation of SES

Judgement of the Transgressions

Moral Justification

Dehumanization of Transgressors

Anomie

Sense of Control

Sociodemographic Data

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Judgment of the Transgression

2.2.2. Moral Justification

2.2.3. Dehumanization of Transgressor

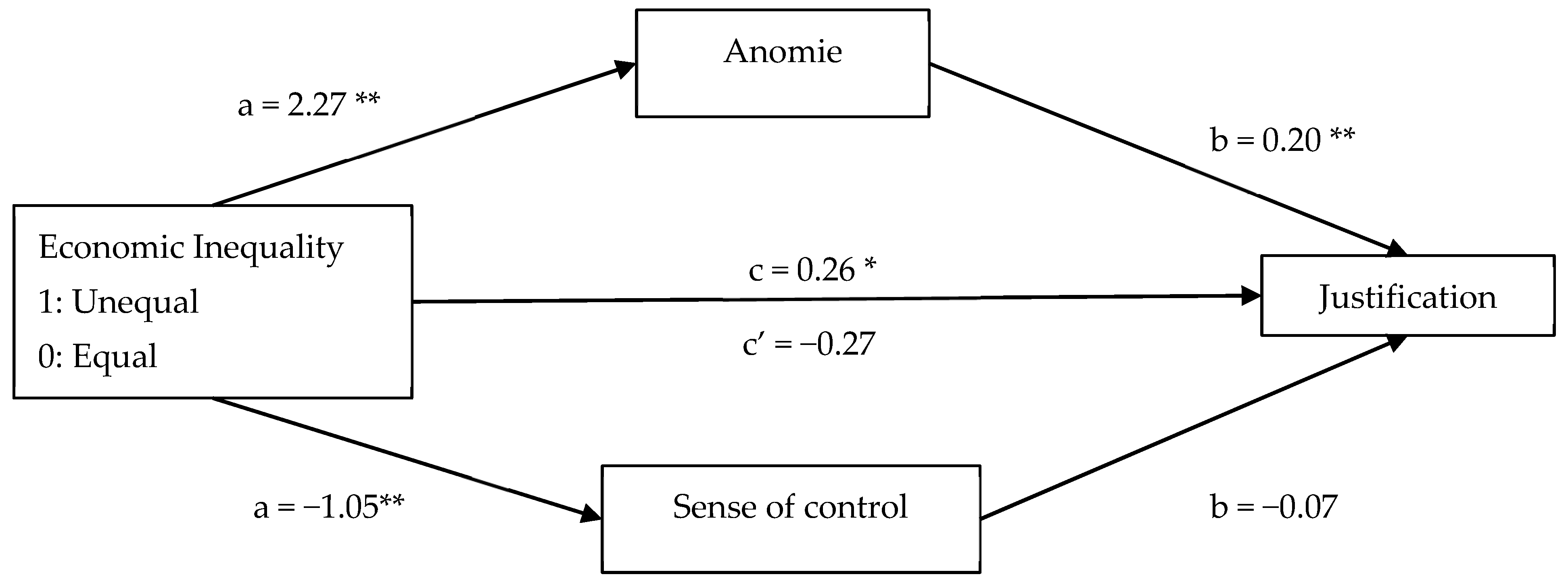

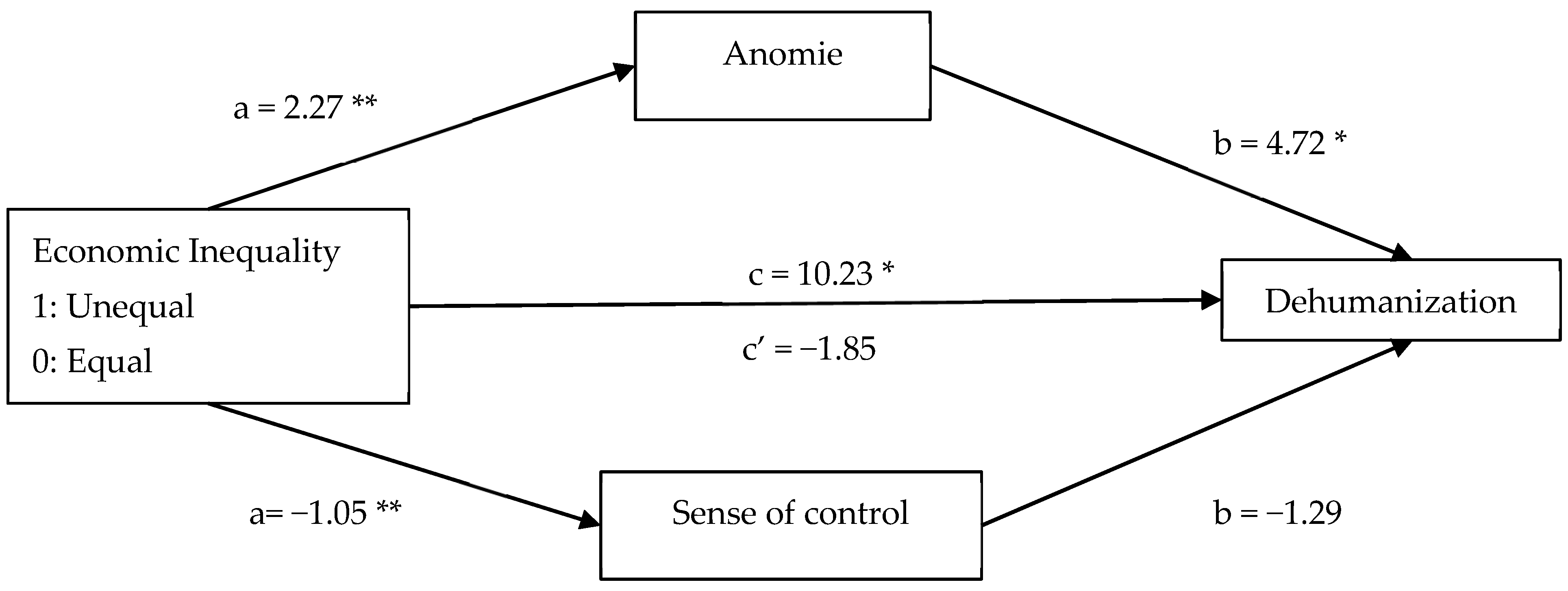

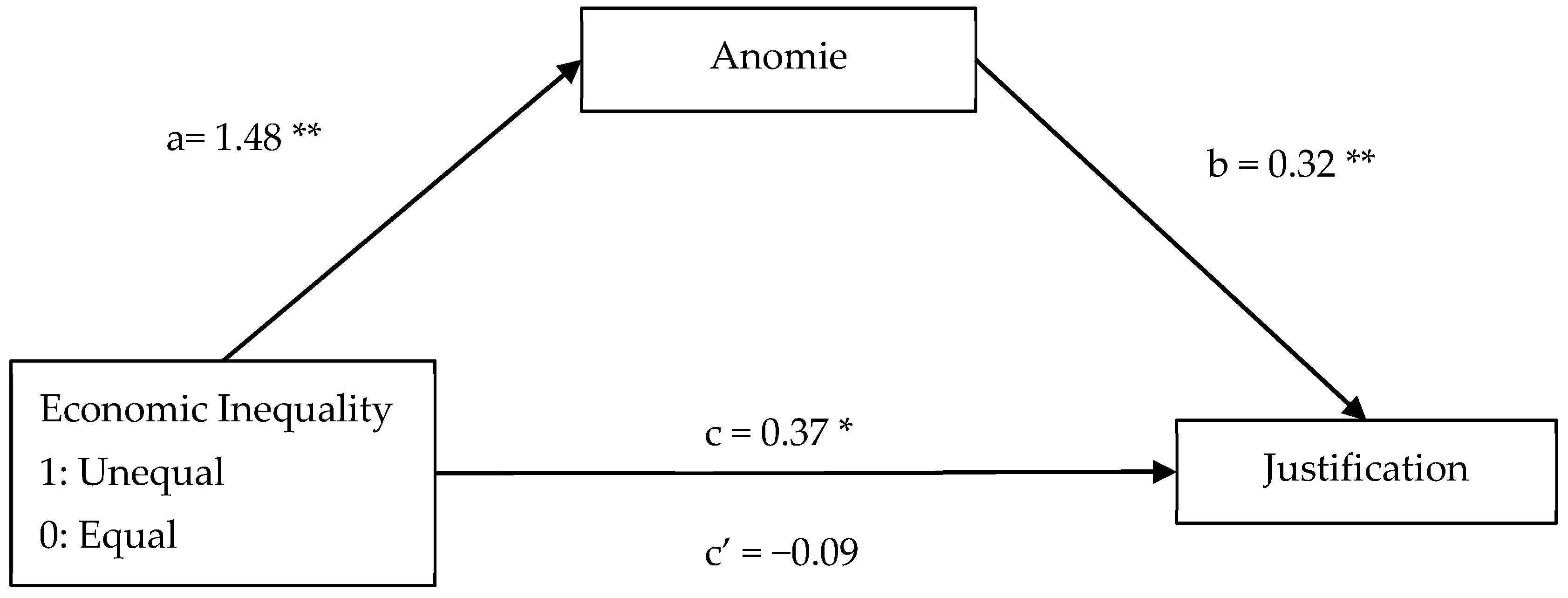

2.2.4. Mediation Analyses

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Design

3.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Sympathy Toward the Transgressor

Upward and Downward Classism

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Judgment of the Transgression

3.2.2. Moral Justification

3.2.3. Dehumanization of Transgressor

3.2.4. Sympathy Toward the Transgressor

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

Limitations and Future Studies

5. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B., Denson, T. F., & Haslam, N. (2013). The roles of dehumanization and moral outrage in retributive justice. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casara, B. G. S., Suitner, C., & Jetten, J. (2022). The impact of economic inequality on conspiracy beliefs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 98, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Xia, X. J., Betancor, V., Chas, A., & Rodríguez-Pérez, A. (2022). Gender inequality in incivility: Everyone should be polite, but it is fine for some of us to be impolite. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 966045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbow, A. J., Cannella, E., Vispoel, W., Morris, C. A., Cederberg, C., Conrad, M., Rice, A. J., & Liu, W. M. (2016). Development of the Classism Attitudinal Profile (CAP). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidai, S. (2018). Why do Americans believe in economic mobility? Economic inequality, external attributions of wealth and poverty, and the belief in economic mobility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J., & Struthers, C. W. (2006). The reduction of psychological aggression across varied interpersonal contexts through repentance and forgiveness. Aggressive Behavior, 32(3), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragale, A. R., Overbeck, J. R., & Neale, M. A. (2011). Resources versus respect: Social judgments based on targets’ power and status positions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragale, A. R., Rosen, B., Xu, C., & Merideth, I. (2009). The higher they are, the harder they fall: The effects of wrongdoer status on observer punishment recommendations and intentionality attributions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. J., & Andreychik, M. R. (2014). The social explanatory styles questionnaire: Assessing moderators of basic social-cognitive phenomena including spontaneous trait inference, the fundamental attribution error, and moral blame. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gino, F., & Pierce, L. (2010). Robin Hood under the hood: Wealth-based discrimination in illicit customer help. Organization Science, 21, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G. P., Piazza, J., & Rozin, P. (2014). Moral character predominates in person perception and evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(1), 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H. M., Gray, K., & Wegner, D. M. (2007). Dimensions of mind perception. Science, 315(5812), 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (methodology in the social sciences) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hester, N., & Gray, K. (2020). The moral psychology of raceless, genderless strangers. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(2), 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J., Peters, K., Álvarez, B., Casara, B. G. S., Dare, M., Kirkland, K., Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á., Selvanathan, H. P., Sprong, S., Tanjitpiyanond, P., Wang, Z., & Mols, F. (2021). Consequences of economic inequality for the social and political vitality of society: A social identity analysis. Political Psychology, 42, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J., Wang, Z., Steffens, N. K., Mols, F., Peters, K., & Verkuyten, M. (2017). A social identity analysis of responses to economic inequality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M., & Van Helvoort, M. (2019). A model of neutralization techniques. Deviant Behavior, 40(10), 1260–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M., Rotman, J. D., & Piazza, J. (2016). Perceiving the agency of harmful agents: A test of dehumanization versus moral typecasting accounts. Cognition, 146, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatry, P., Manokara, K., & Harris, L. T. (2021). Socioeconomic status and dehumanization in India: Elaboration of the stereotype content model in a non-WEIRD sample. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(6), 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, K., Van Lange, P. A., Gorenz, D., Blake, K., Amiot, C. E., Ausmees, L., Baguma, P., Barry, O., Becker, M., Bilewicz, M., Boonyasiriwat, W., Booth, R. W., Castelain, T., Costantini, G., Dimdins, G., Espinosa, A., Finchilescu, G., Fischer, R., Friese, M., … Bastian, B. (2024). High economic inequality is linked to greater moralization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Nexus, 3(7), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H. J., Piff, P. K., Moskowitz, J. P., & Shariff, A. F. (2024). System circumvention: Dishonest-illegal transgressions are perceived as justified in non-meritocratic societies. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(4), 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M. W., Piff, P., & Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 901–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidner, B., Castano, E., & Ginges, J. (2013). Dehumanization, retributive and restorative justice, and aggressive versus diplomatic intergroup conflict resolution strategies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(2), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidner, B., Castano, E., Zaiser, E., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2010). Ingroup glorification, moral disengagement, and justice in the context of collective violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(8), 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, J. P., Paladino, P. M., Rodriguez-Torres, R., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Perez, A., & Gaunt, R. (2000). The emotional side of prejudice: The attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Leidner, B., & Fernandez-Campos, S. (2020). Stepping into perpetrators’ shoes: How ingroup transgressions and victimization shape support for retributive justice through perspective-taking with perpetrators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(3), 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S., & Haslam, N. (2007). Animals and androids: Implicit associations between social categories and nonhumans. Psychological Science, 18, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, B. F. (2021). Moral judgments. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, B. F., Guglielmo, S., & Monroe, A. E. (2014). A theory of blame. Psychological Inquiry, 25(2), 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manstead, A. S., Easterbrook, M. J., & Kuppens, T. (2020). The socioecology of social class. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L., Burk, D., Laperrière, M., & Richeson, J. A. (2017). Exposure to rising inequality shapes Americans’ opportunity beliefs and policy support. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(36), 9593–9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, A. E., Brady, G. L., & Malle, B. F. (2017). This isn’t the free will worth looking for: General free will beliefs do not influence moral judgments, agent-specific choice ascriptions do. Social. Psychological and Personality Science, 8(2), 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, E., & Nadler, J. (2008). Moral spillovers: The effect of moral violations on deviant behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P. K., & Robinson, A. R. (2017). Social class and prosocial behavior: Current evidence, caveats, and questions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, E., Pettit, N. C., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (2013). Effects of wrongdoer status on moral licensing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(4), 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M., Martínez, R., Matamoros-Lima, J., Moya, M., & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2024). Perceived economic inequality enlarges the perceived humanity gap between low-and high-socioeconomic status groups. The Journal of Social Psychology, 164(5), 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M., Martínez, R., Moya, M., & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2019). Animalizing the disadvantaged, mechanizing the wealthy: The convergence of socio-economic status and attribution of humanity. International Journal of Psychology, 54(4), 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M. (2013). White collar crime and morality: How occupation shapes perception [Doctoral dissertation, West Virginia University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, F., Djeriouat, H., & Trémolière, B. (2021). Too rich to be forgiven? Economic resources shape moral judgment of accidental harm. OSF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E., Mazar, N., Alter, A. L., & Ariely, D. (2014). Financial deprivation selectively shifts moral standards and compromises moral decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(2), 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. C., Wild, E., & Colquitt, J. A. (2003). To justify or excuse?: A meta-analytic review of the effects of explanations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, N., & Pitesa, M. (2018). The macroeconomic environment and the psychology of work evaluation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, S., Jetten, J., Wang, Z., Peters, K., Mols, F., Verkuyten, M., Bastian, B., Ariyanto, A., Autin, F., Ayub, N., Badea, C., Besta, T., Butera, F., Costa-Lopes, R., Cui, L., Fantini, C., Finchilescu, G., Gaertner, L., Gollwitzer, M., … Wohl, M. J. A. (2019). “Our country needs a strong leader right now”: Economic inequality enhances the wish for a strong leader. Psychological Science, 30(11), 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanjitpiyanond, P., Jetten, J., & Peters, K. (2022). How economic inequality shapes social class stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 98, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L., Herian, M. N., & Diener, E. (2014). Detrimental effects of corruption and subjective well-being whether, how, and when. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(7), 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoori, A., Bastian, B., & Jetten, J. (2017). Toward a psychological analysis of anomie. Political Psychology, 38(6), 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoori, A., Jetten, J., Bastian, B., Ariyanto, A., Autin, F., Ayub, N., Badea, C., Besta, T., Butera, F., Costa-Lopes, R., Cui, L., Fantini, C., Finchilescu, G., Gaertner, L., Gollwitzer, M., Gómez, Á., González, R., Hong, Y. Y., Jensen, D. H., … Wohl, M. (2016). Revisiting the measurement of anomie. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, C., Wiwad, D., & Kouchaki, M. (2023). Economic inequality reduces sense of control and increases the acceptability of self-interested unethical behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(10), 2747–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, J. A. (2002). Moral rationalization and the integration of situational factors and psychological processes in immoral behavior. Review of General Psychology, 6(1), 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, D. S., & Laurent, S. M. (2021). The (income-adjusted) price of good behavior: Documenting the counter-intuitive, wealth-based moral judgment gap. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(3), 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Unequal Condition | Equal Condition | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | Effect | F | η2p | ||

| Judgment of the transgression | High-SES | 6.66(0.40) | 6.40(0.68) | SES | 122.47 ** | 0.301 |

| Low-SES | 5.30(0.98) | 5.82(0.81) | Inequality | 2.16 | 0.008 | |

| SES × Inequality | 19.67 ** | 0.065 | ||||

| Justification | High-SES | 3.09(1.24) | 2.99(1.08) | SES | 2.426 | 0.008 |

| Low-SES | 3.44(0.81) | 3.01(0.74) | Inequality | 4.98 * | 0.017 | |

| SES × Inequality | 1.993 | 0.007 | ||||

| Dehumanization | High-SES | 43.59(32.19) | 34.21(26.49) | SES | 10.324 ** | 0.035 |

| Low-SES | 28.15(24.93) | 17.60(19.77) | Inequality | 26.73 ** | 0.086 | |

| SES × Inequality | 0.036 | 0.000 | ||||

| Unequal Condition | Equal Condition | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | M(SD) | Effect | F | η2p | ||

| Judgment of the transgression | High-SES | 6.38(0.93) | 6.47(0.78) | SES | 54.124 ** | 0.120 |

| Low-SES | 5.66(1.10) | 5.76(1.02) | Inequality | 0.941 | 0.002 | |

| SES × Inequality | 0.009 | 0.000 | ||||

| Justification | High-SES | 3.56(1.50) | 3.29(1.57) | SES | 6.82 * | 0.017 |

| Low-SES | 4.02(1.15) | 3.55(1.21) | Inequality | 7.09 * | 0.018 | |

| SES × Inequality | 0.509 | 0.001 | ||||

| Dehumanization | High-SES | 57.63(32.49) | 48.66(30.69) | SES | 23.99 ** | 0.057 |

| Low-SES | 39.44(28.32) | 37.02(28.66) | Inequality | 3.50 | 0.009 | |

| SES x Inequality | 1.16 | 0.003 | ||||

| Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff (SE) | 95% CI | Coeff (SE) | 95% CI | Coeff (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Judgment of transgression | 0.65(0.09) | [0.467, 0.833] | 0.45(0.10) | [0.248, 0.644] | 0.20(0.05) | [0.109, 0.318] |

| Justification | −0.34, (0.13) | [−0.603, −0.084] | −0.05, (0.14) | [−0.335, 0.228] | −0.29(0.07) | [−0.452, −0.149] |

| Dehumanization | 14.52, (3.07) | [8.482, 20.561] | 2.29, (3.11) | [−3.826, 8.401] | 12.23(1.88) | [8.755, 16.116] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Álamo-Hernández, A.; Sainz, M.; Betancor, V.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A. Moral Judgments Across the Economic Divide: The Effect of Perceived Economic Inequality and Status in Judgment of Transgressions, Justification, and Dehumanization. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101317

Álamo-Hernández A, Sainz M, Betancor V, Rodríguez-Pérez A. Moral Judgments Across the Economic Divide: The Effect of Perceived Economic Inequality and Status in Judgment of Transgressions, Justification, and Dehumanization. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101317

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁlamo-Hernández, Alba, Mario Sainz, Verónica Betancor, and Armando Rodríguez-Pérez. 2025. "Moral Judgments Across the Economic Divide: The Effect of Perceived Economic Inequality and Status in Judgment of Transgressions, Justification, and Dehumanization" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101317

APA StyleÁlamo-Hernández, A., Sainz, M., Betancor, V., & Rodríguez-Pérez, A. (2025). Moral Judgments Across the Economic Divide: The Effect of Perceived Economic Inequality and Status in Judgment of Transgressions, Justification, and Dehumanization. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101317