Family-to-Work Conflict and Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers: The Mediating Effect of Work Stress and the Moderating Effect of Gender

Abstract

1. Introduction

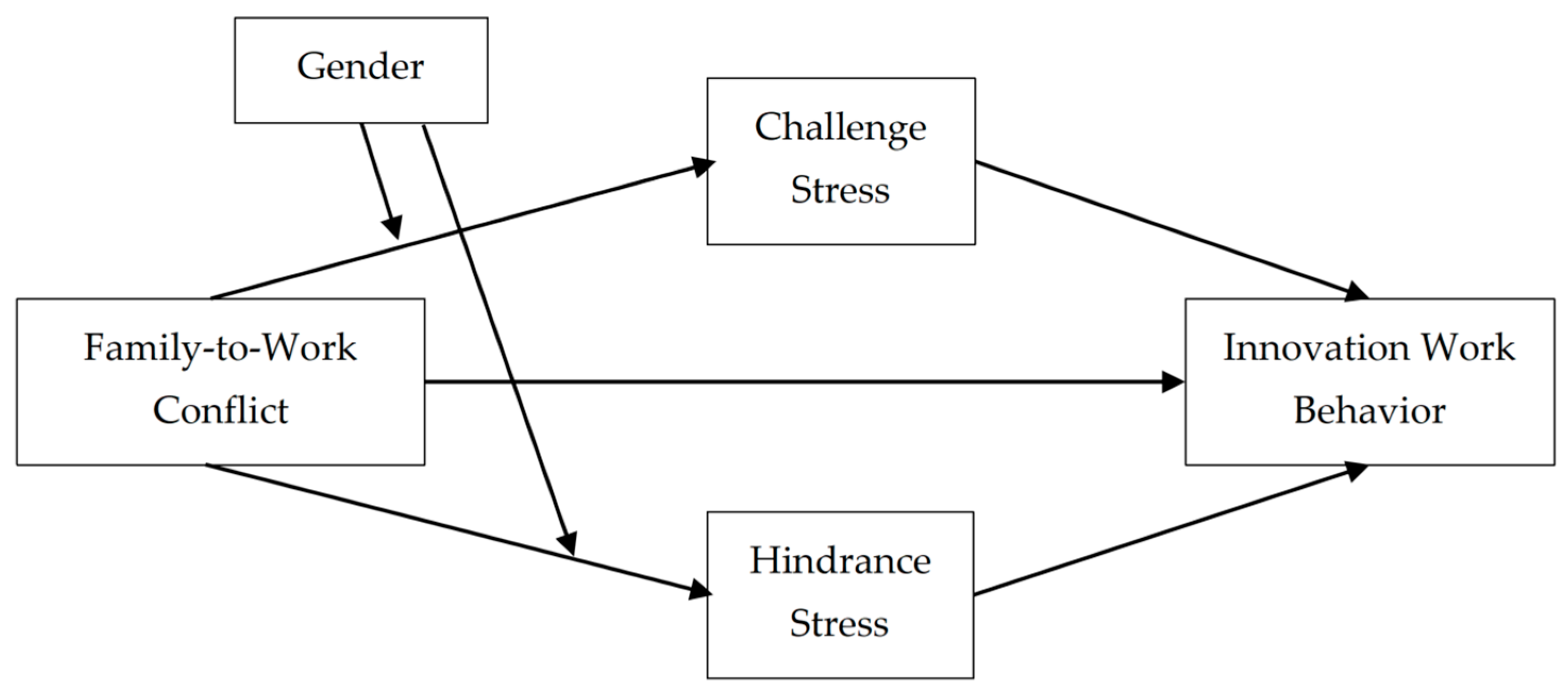

1.1. Family-to-Work Conflict and Teachers’ Innovative Work Behavior

1.2. Work Stress Mediates the Relationship Between Family-to-Work Conflict and Teachers’ Innovative Work Behavior

1.3. Gender Moderates the Relationship Between Family-to-Work Conflict and Work Stress

1.4. Aims of the Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Family-to-Work Conflict

2.2.2. Work Stress

2.2.3. Teachers’ Innovative Work Behavior

2.2.4. Gender

2.3. Method of Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

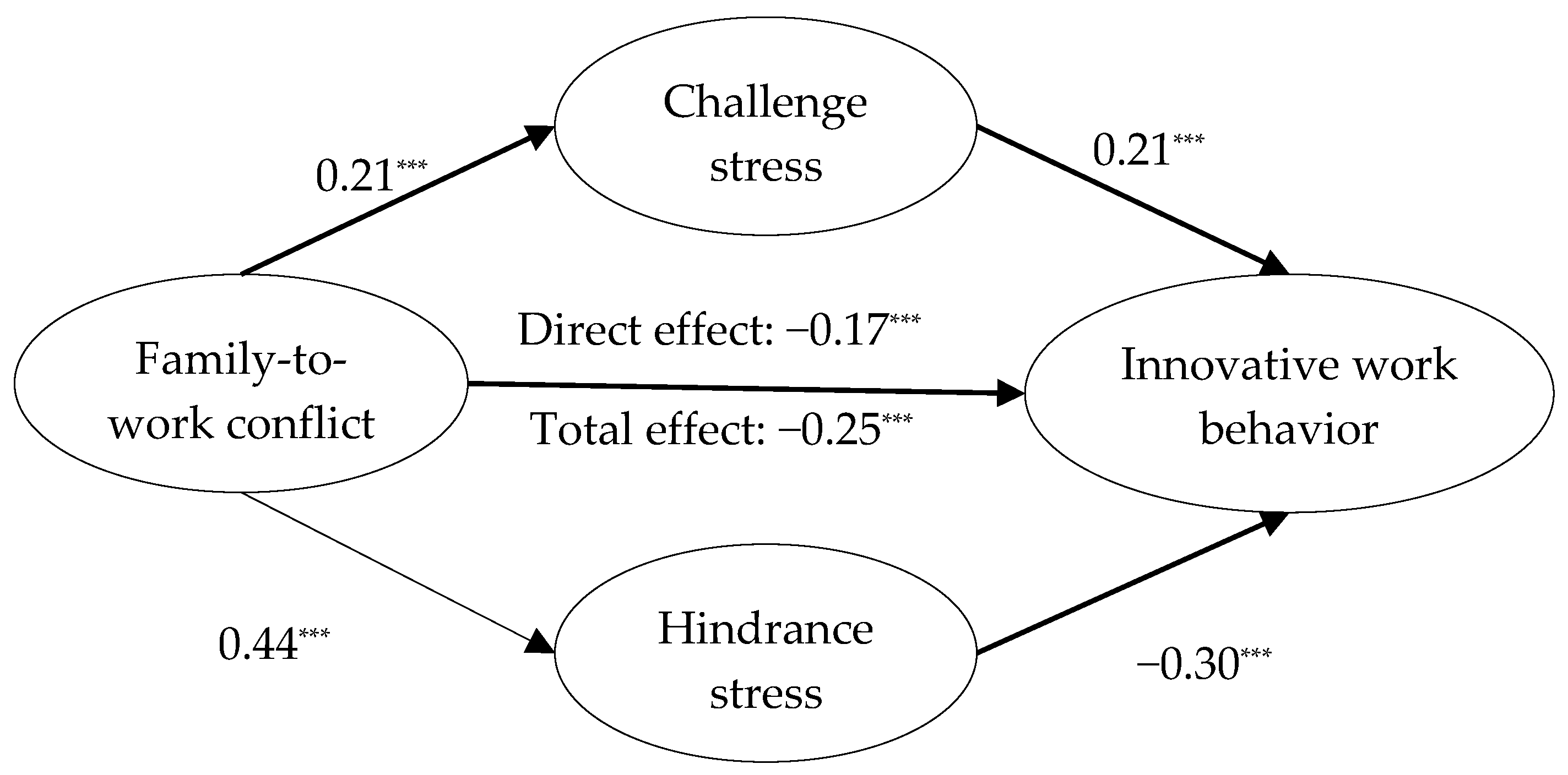

3.2. The Mediating Effects of Challenge Stress and Hindrance Stress

3.3. The Moderating Role of Gender in the Relationship Between Family-to-Work Conflict and Work Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Family-to-Work Conflict and Teachers’ Innovative Work Behavior

4.2. The Mediating Role of Work Stress

4.3. The Moderating Role of Gender

4.4. Implications and Limitations of This Research

4.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aryani, R., Widodo, W., & Susila, S. (2024). Model for social intelligence and teachers’ innovative work behavior: Serial mediation. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2312028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. H., & Hu, Y. W. (2022). Professional motherhood: Identity adjustment and integration of female teachers. Journal of Soochow University (Educational Science Edition), 10(2), 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2002). Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work-family conflict. Sex Roles, 47(11–12), 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G., Lin, H., & Xie, J. (2020). The impact of challenging-hindering work stress on insomnia: The mediating role of positive-negative work rumination. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(05), 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P. C., Ni, Q., & Jia, Y. L. (2014). Does pressure facilitate or inhibit innovation? A dual-pressure perspective on the relationship between stress and innovative behavior, mediated by perceived organizational support. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 31(16), 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C. M. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. The Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1112–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C., & Bettencourt, C. (2022). The effect of work-family conflict and hindrance stress on nurses’ satisfaction: The role of ethical leadership. Personnel Review, 51(3), 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S., & Haghighi Shirazi, Z. R. (2021). Towards teacher innovative work behavior: A conceptual model. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1869364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. J. (2024). Impact of challenge hindrance stress and work family conflict on occupational stress of ophthalmic nurses. Occupation and Health, 40(09), 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lepine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lepine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Gao, J., Wang, Z., & You, X. Q. (2016). Regulatory focus and teachers’ innovative work behavior: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 14(01), 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q., & Liu, M. (2023). The effect of family supportive supervisor behavior on teachers’ innovative behavior and thriving at work: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1129486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Yin, H. (2021). How work-family conflict affects employees’ innovative behavior: A mediation model under organizational identification. Journal of Xihua University (Philosophy & Social Sciences), 40(04), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Zhou, Y., & Shi, Q. (2017). Research on negative outcomes of organizational citizenship behavior: Based on generalized exchange, impression management and evolutionary psychology. Management Review, 29(04), 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. (2025). Exploring the mediating role of social support and self-efficacy in the relationship between work family conflict and mental health outcomes in China. Current Psychology, 44(5), 3197–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & Mcmurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solichin, M., Andriansyah, E., Rachmawati, R., Cahyani, F., Nuris, D., & Rafsanjani, M. (2023). Work-family conflict and innovative teaching among Indonesian teachers: The mediating role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Jiao, H., & Wang, C. (2023). How work-family conflict affects knowledge workers’ innovative behavior: A spillover-crossover-spillover model of dual-career couples. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(9), 2499–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Zhang, L., & Zhang, J. (2020). The impact mechanism of work-family conflict on innovative behavior of knowledge workers. Management Review, 32(03), 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q., & Jiang, M. (2023). ‘Ideal employees’ and ‘good wives and mothers’: Influence mechanism of bi-directional work–family conflict on job satisfaction of female university teachers in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1166509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y. L., Chen, Y. W., & Zhang, Y. T. (2021). Relationship between work stress and mental health of information technology employees. Occupation and Health, 37(05), 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. J. (2010). Study on college teachers’ work-family conflict and job burnout: The mediation role of social support. Education Research Monthly, (9), 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Lan, Y., & Li, C. (2022). Challenge-hindrance stressors and innovation: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(4), 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Peng, J. (2017). Work-family conflict and depression in Chinese professional women: The mediating roles of job satisfaction and life satisfaction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(2), 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., & Sang, Z. Q. (2019). The child-rearing dilemmas and parenting anxieties of new-generation mothers: A sociopsychological analysis of the Mid-aged Mother demographic in new media contexts. China Youth Study, (10), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Song, Y., Zuo, M., Zhai, L., & Zhang, M. (2024). Job stressors and the innovative work behavior of STEM teachers: Serial multiple mediation role of creative self-efficacy and creative motivation. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–19, (Early Access). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Wen, Z., Ma, Y., Cai, B., & Liu, X. (2024). Associations among challenge stress, hindrance stress, and employees’ innovative work behavior: Mediation effects of thriving at work and emotional exhaustion. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 58, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., Fan, Y., & Yao, H. (2024). Effects and mechanisms of challenge-hindrance stressors on teachers’ innovative work behavior. Modern Education Review, 259(05), 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Liao, C., Huang, L., Li, Z., Xiao, H., & Pan, Y. (2024). The positive side of stress: Investigating the impact of challenge stressors on innovative behavior in higher education. Acta Psychologica, 246, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M., & Zhang, L. (2012). The relationship between teachers’ innovative work behavior and innovation atmosphere. Chinese Journal of Ergonomics, 18(03), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 202 | 22.1 |

| Female | 714 | 77.9 | |

| Education Background | Associate degree or below | 19 | 2.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 448 | 48.9 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 449 | 49.0 | |

| Teaching Experience | 1–3 years | 156 | 17.0 |

| 4–10 years | 291 | 31.8 | |

| 11–15 years | 191 | 20.9 | |

| 16–20 years | 123 | 13.4 | |

| Over 20 years | 155 | 16.9 | |

| Professional Titles | Unrated | 262 | 28.6 |

| Lecturer (Intermediate) | 398 | 43.4 | |

| Associate Professor (Associate Senior) | 219 | 23.9 | |

| Professor (Full Senior) | 37 | 4.0 | |

| M | SD | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family-to-work conflict | 2.43 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.21 |

| 2. Challenge stress | 3.76 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.66 | 0.20 *** | 0.81 | 0.34 | 0.11 |

| 3. Hindrance stress | 2.67 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 0.40 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.71 | 0.30 |

| 4. Innovative work behavior | 4.27 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.51 | −0.18 *** | 0.09 ** | −0.25 *** | 0.71 |

| Path | Gender | β | SE | 95% CI | Differences in CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWC→CHWS | Male | 0.35 *** | 0.09 | 0.18, 0.51 | 2.52 *** |

| Female | 0.16 *** | 0.05 | 0.07, 0.24 | ||

| FWC→HIWS | Male | 0.62 *** | 0.07 | 0.46, 0.75 | 2.87 ** |

| Female | 0.37 *** | 0.05 | 0.27, 0.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, X.; Dong, J.; Guo, J. Family-to-Work Conflict and Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers: The Mediating Effect of Work Stress and the Moderating Effect of Gender. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101309

Bao X, Dong J, Guo J. Family-to-Work Conflict and Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers: The Mediating Effect of Work Stress and the Moderating Effect of Gender. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101309

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Xiaohong, Jia Dong, and Jianwen Guo. 2025. "Family-to-Work Conflict and Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers: The Mediating Effect of Work Stress and the Moderating Effect of Gender" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101309

APA StyleBao, X., Dong, J., & Guo, J. (2025). Family-to-Work Conflict and Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers: The Mediating Effect of Work Stress and the Moderating Effect of Gender. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101309