Psychosocial Adaptation After Heart Transplantation: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety on Social Support and Quality of Life in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Support and Quality of Life

1.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem

1.3. The Mediating Role of Death Anxiety

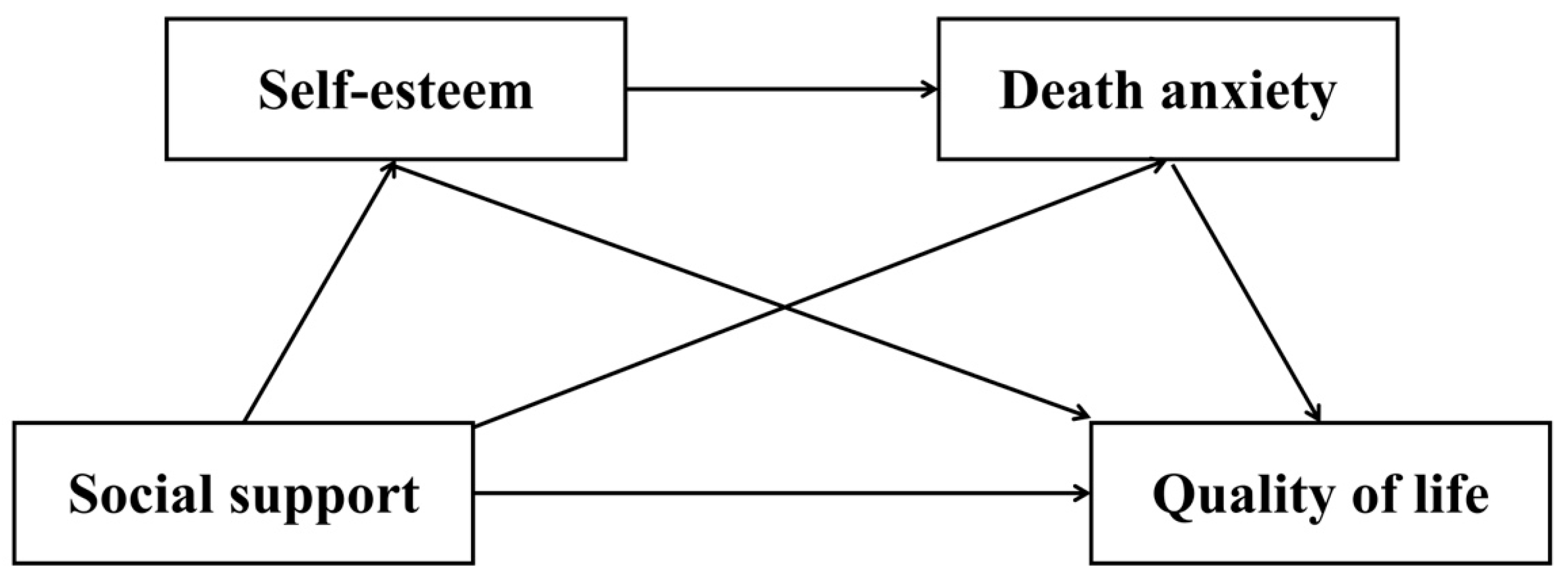

1.4. The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety

1.5. Cultural Context of Heart Transplantation in China

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Support Rating Scale

2.2.2. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

2.2.3. Templer Death Anxiety Scale

2.2.4. SF-36 Health Survey

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Variance Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

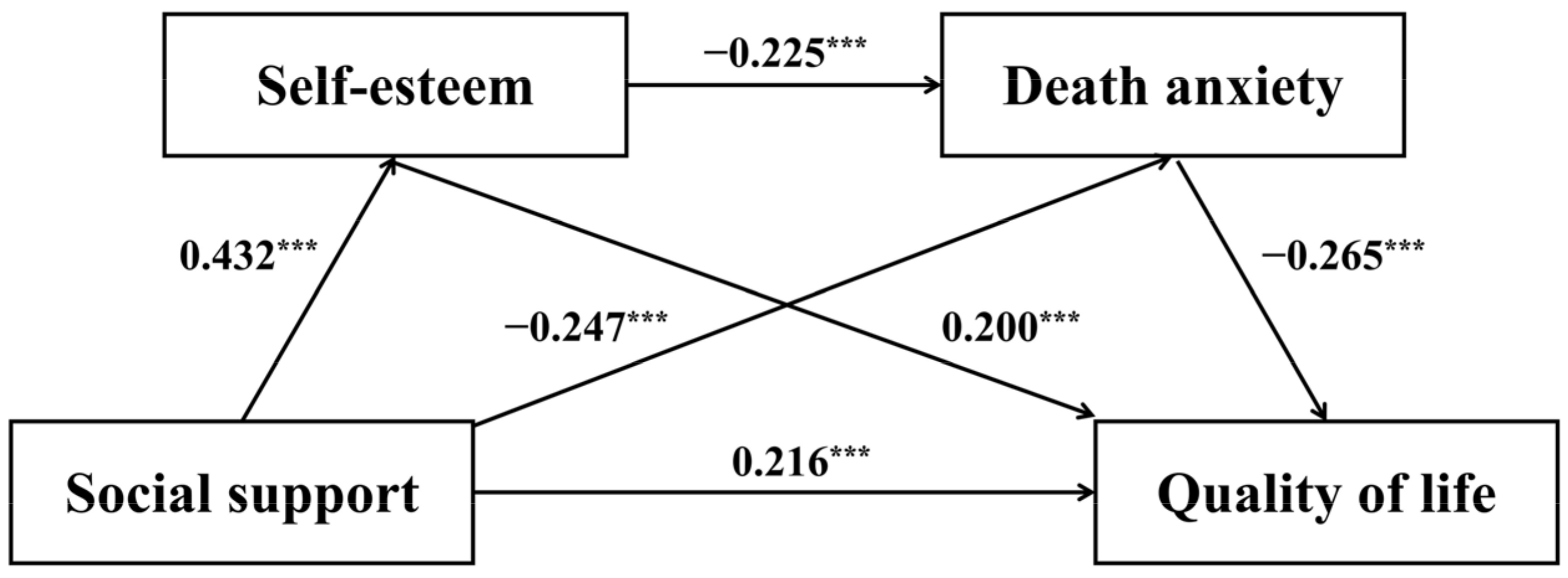

3.3. Mediation Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Social Support on Quality of Life

4.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety

4.3. The Chain Mediation Through Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety

5. Implications

6. Limitations and Research Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SS | Social Support |

| SE | Self-Esteem |

| DA | Death Anxiety |

References

- Adejumo, O. A., Jinabhai, C., Daniel, O., & Haffejee, F. (2025). The effects of stigma and social support on the health-related quality of life of people with drug resistance tuberculosis in Lagos, Nigeria. Quality of Life Research, 34(5), 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsyi, D. H., Permana, P. B. D., & Karim, R. I. (2022). The role of optimism in manifesting recovery outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 162, 111044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, Y., Li, M., Yu, M., & Wu, H. (2021). The effect of fear of progression on quality of life among breast cancer patients: The mediating role of social support. Health and Quality of life Outcomes, 19, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalat, G., Plasse, J., Gauthier, E., Verdoux, H., Quiles, C., Dubreucq, J., Legros-Lafarge, E., Jaafari, N., Massoubre, C., & Guillard-Bouhet, N. (2022). The central role of self-esteem in the quality of life of patients with mental disorders. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Cardiovascular Health and Disease Report Writing Group. (2023). Summary of china cardiovascular health and disease report 2022. Chinese Circulation Journal, 38(6), 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Kang, D., Shin, D. W., Kim, N., Lee, S. K., Lee, J. E., Nam, S. J., & Cho, J. (2024). Social support during re-entry period and long-term quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A 10-year longitudinal cohort study. Quality of Life Research, 33(5), 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J. O. K., Li, W. H. C., Cheung, A. T., Ho, L. L. K., Xia, W., Chan, G. C. F., & Lopez, V. (2021). Relationships among resilience, depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and quality of life in children with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 30(2), 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, M., Daniel, C., & Lamont, M. (2016). Destigmatization and health: Cultural constructions and the long-term reduction of stigma. Social Science & Medicine, 165, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, M. A., Rosenberger, E. M., Myaskovsky, L., DiMartini, A. F., Dabbs, A. J. D., Posluszny, D. M., Steel, J., Switzer, G. E., Shellmer, D. A., & Greenhouse, J. B. (2016). Depression and anxiety as risk factors for morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation, 100(5), 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y., Zhang, H., Hu, Z., Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Ding, B., Yue, G., & He, Y. (2024). Perceived social support and health-related quality of life among hypertensive patients: A latent profile analysis and the role of delay discounting and living alone. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 17, 2125–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dun, L., Xian-Yi, W., & Si-Ting, H. (2022). Effects of cognitive training and social support on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 21, 15347354221081271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hadi, S. N., Zanotti, R., & Danielis, M. (2025). Lived experiences of persons with heart transplantation: A systematic literature review and meta-synthesis. Heart & Lung, 69, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Fatma, C., Cigdem, C., Emine, C., & Omer, B. (2021). Life experiences of adult heart transplant recipients: A new life, challenges, and coping. Quality of Life Research, 30, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, M., Tanguay-Sabourin, C., Parisien, M., Zare, A., Guglietti, G. V., Norman, J., Petre, B., Bortsov, A., Ware, M., & Perez, J. (2025). Biological markers and psychosocial factors predict chronic pain conditions. Nature Human Behaviour, 9, 1710–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C., Gui, S., Zhu, L., Bian, X., Shen, H., & Jiao, C. (2025). Social support and quality of life in Chinese heart transplant recipients: Mediation through uncertainty in illness and moderation by psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1637110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R., Costa, P., & Adonu, J. (2004). Social support and its consequences: ‘Positive’and ‘deficiency’values and their implications for support and self-esteem. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43(3), 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. (2022). Supportive care and end of life. In Promoting healing and resilience in people with cancer: A nursing perspective (pp. 531–574). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, L., Wu, T., Yang, J., Xie, X., Han, S., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Self-esteem and cultural worldview buffer mortality salience effects on responses to self-face: Distinct neural mediators. Biological Psychology, 155, 107944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihasani, M., & Naderi, N. (2021). Death anxiety in the elderly: The role of spiritual health and perceived social support. Aging Psychology, 6(4), 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, M., Azim, W., Hussain, W., Rehman, F. U., Salam, A., & Rafique, M. (2022). Quality of life, perceived social support and death anxiety among people having cardiovascular disorders: A cross-sectional study. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences, 16(4), 460. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hettwer, M. D., Dorfschmidt, L., Puhlmann, L. M., Jacob, L. M., Paquola, C., Bethlehem, R. A., Consortium, N., Bullmore, E. T., Eickhoff, S. B., & Valk, S. L. (2024). Longitudinal variation in resilient psychosocial functioning is associated with ongoing cortical myelination and functional reorganization during adolescence. Nature Communications, 15(1), 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y., Yuhan, L., Youhui, G., Zhanying, W., Shili, Z., Xiaoting, H., & Wenhua, Y. (2022). Death anxiety among advanced cancer patients: A cross-sectional survey. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(4), 3531–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N., Yang, Z., & Wang, A. (2024). Early post-transplant adaptation experience in young and middle-aged people with kidney transplant in China: A qualitative study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 46(5), 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y., Guan, Z., Yan, F., Wiley, J. A., Reynolds, N. R., Tang, S., & Sun, M. (2022). Mediator role of presence of meaning and self-esteem in the relationship of social support and death anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1018097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2023). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM.

- Ishikawa, A., Rickwood, D., Bariola, E., & Bhullar, N. (2023). Autonomy versus support: Self-reliance and help-seeking for mental health problems in young people. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 58(3), 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverach, L., Menzies, R. G., & Menzies, R. E. (2014). Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaberi, M., Mohammadi, T. K., Adib, M., Maroufizadeh, S., & Ashrafi, S. (2025). The relationship of death anxiety with quality of life and social support in hemodialysis patients. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 90(4), 1894–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P., Zhang, L., Gao, Z., Ji, Q., Xu, J., Chen, Y., Song, M., & Guo, L. (2024). Relationship between self-esteem and quality of life in middle-aged and older patients with chronic diseases: Mediating effects of death anxiety. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q., Zhang, L., Xu, J., Ji, P., Song, M., Chen, Y., & Guo, L. (2024). The relationship between stigma and quality of life in hospitalized middle-aged and elderly patients with chronic diseases: The mediating role of depression and the moderating role of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1346881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N., Ye, H., Zhao, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). The association between social support and the quality of life of older adults in China: The mediating effect of loneliness. Experimental Aging Research, 51(2), 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeğer, A., Aydın, M., Altınbaş, K., Cansız, A., Tan, Ö., Tomar Bozkurt, H., Eğilmez, Ü., Tekdemir, R., Şen, B., & Aktuğ Demir, N. (2021). Evaluation of the relationship between perceived social support, coping strategies, anxiety, and depression symptoms among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 56(4), 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanbabai Ghaleie, P., Hooman, F., Naderi, F., Talebzadeh Shoushtari, M., & Gatezadeh, A. (2024). The role of social support and spiritual health in predicting death anxiety in patients with cancer. Hospital Practices and Research, 9(3), 515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Kisomi, Z. S., Taherkhani, O., Mollaei, M., Esmaeily, H., Shirkhanloo, G., Hosseinkhani, Z., & Amerzadeh, M. (2024). The moderating role of social support in the relationship between death anxiety and resilience among dialysis patients. BMC Nephrology, 25(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobbe, T. J., Kremer, D., Bültmann, U., Annema, C., Navis, G., Berger, S. P., Bakker, S. J. L., & Meuleman, Y. (2025). Insights into health-related quality of life of kidney transplant recipients: A narrative review of associated factors. Kidney Medicine, 7(5), 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristianto, Y. D., & Yudiarso, A. (2025). A meta-analysis correlation social support and quality of life. Jurnal Psikologi Tabularasa, 20(1), 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, B. C. (2013). Collectivism and coping: Current theories, evidence, and measurements of collective coping. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lehto, R., & Stein, K. F. (2009). Death anxiety: An analysis of an evolving concept. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G. N., Cohen, B. E., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Fleury, J., Huffman, J. C., Khalid, U., Labarthe, D. R., Lavretsky, H., Michos, E. D., & Spatz, E. S. (2021). Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 143(10), e763–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Li, Y., Lam, A. I. F., Tang, W., Seedat, S., Barbui, C., Papola, D., Panter-Brick, C., Waerden, J. V., Bryant, R., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Gémes, K., Purba, F. D., Setyowibowo, H., Pinucci, I., Palantza, C., Acarturk, C., Kurt, G., Tarsitani, L., … Hall, B. J. (2023). Understanding the protective effect of social support on depression symptomatology from a longitudinal network perspective. BMJ Ment Health, 26(1), e300802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Qin, S., Zhu, Y., Zhou, Q., Yi, A., Mo, C., Gao, J., Chen, J., Wang, T., & Feng, Z. (2025). Social support mediates the relationship between depression and subjective well-being in elderly patients with chronic diseases: Evidence from a survey in Rural Western China. PLoS ONE, 20(6), e0325029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C., Zhu, X., Wang, X., Wang, L., Wu, Y., Hu, X., Wen, J., & Cong, L. (2025). The impact of perceived social support on chronic disease self-management among older inpatients in China: The chain-mediating roles of psychological resilience and health empowerment. BMC Geriatrics, 25(1), 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D., Liang, D., Huang, M., Xu, X., Bai, Y., & Meng, D. (2024). The dyadic effects of family resilience and social support on quality of life among older adults with chronic illness and their primary caregivers in multigenerational families in China: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon, 10(5), e27351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S., Liu, D., Niu, G., & Longobardi, C. (2022). Active social network sites use and loneliness: The mediating role of social support and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 41(3), 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Chang, S., Wang, Z., & Raja, F. Z. (2024). Exploring the association between social support and anxiety during major public emergencies: A meta-analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health, 12, 1344932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., & Bai, S. (2024). Downward intergenerational support and well-being in older chinese adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(11), 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., Ji, Y., Liu, Y. h., Sun, H., Tang, S., & Li, X. (2023). Relationships among social support, coping style, self-stigma, and quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: A multicentre, cross-sectional study. International Wound Journal, 20(3), 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthner, O. E., De Luca, E., Poole, J. M., Abbey, S. E., Shildrick, M., Gewarges, M., & Ross, H. J. (2015). Heart transplants: Identity disruption, bodily integrity and interconnectedness. Health, 19(6), 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merati, M., Jalali, A., Naghibzadeh, A., Salari, N., & Moradi, K. (2024). Study of the relationship between death anxiety and quality of life in patients with heart failure. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 00302228241301654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaniak, I., Rużyczka, E. W., Dębska, G., Król, B., Wierzbicki, K., Tomaszek, L., & Przybyłowski, P. (2020). Level of life quality in heart and kidney transplant recipients: A multicenter study. Transplantation Proceedings, 52(7), 2081–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalois, Z.-A., & Papalois, V. (2023). Health-related quality of life and patient reported outcome measures following transplantation surgery. In Patient reported outcomes and quality of life in surgery (pp. 215–240). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S., Sheehan, L., Yau, E., Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Deng, H., Lam, C., Chen, Z., Zhao, L., CBPR Team & Corrigan, P. (2024). Adapting and evaluating a strategic disclosure program to address mental health stigma among Chinese. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22(3), 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B., Rea, K. E., Claar, R. L., van Tilburg, M. A., & Levy, R. L. (2021). Passive coping associations with self-esteem and health-related quality of life in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 670902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Religioni, U., Barrios-Rodríguez, R., Requena, P., Borowska, M., & Ostrowski, J. (2025). Enhancing Therapy adherence: Impact on clinical outcomes, healthcare costs, and patient quality of life. Medicina, 61(1), 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimé, B., Bouchat, P., Paquot, L., & Giglio, L. (2020). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social outcomes of the social sharing of emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, E. M., Fox, K. R., DiMartini, A. F., & Dew, M. A. (2012). Psychosocial factors and quality-of-life after heart transplantation and mechanical circulatory support. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation, 17(5), 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, H., Abbey, S., De Luca, E., Mauthner, O., McKeever, P., Shildrick, M., & Poole, J. (2010). What they say versus what we see:“Hidden” distress and impaired quality of life in heart transplant recipients. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 29(10), 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjapong, U., & Thongtip, S. (2023). Association between self-esteem and health-related quality of life among elderly rural community, Northern Thailand. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(2), 2282410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, L. Y., & Hansel, T. C. (2024). Psychological and social determinants of adaptation: The impact of finances, loneliness, information access and chronic stress on resilience activation. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1245765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabert, J., Browne, J. L., Mosely, K., & Speight, J. (2013). Social stigma in diabetes: A framework to understand a growing problem for an increasing epidemic. The Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shildrick, M. (2015). Staying alive: Affect, identity and anxiety in organ transplantation. Body & Society, 21(3), 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, E., & Makarova, M. (2025). Existential concerns arising from a threat to the belief in a just world: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 00221678251322250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. L., Bergeron, C. D., Riggle, S. D., Meng, L., Towne, S. D., Jr., Ahn, S., & Ory, M. G. (2017). Self-care difficulties and reliance on support among vulnerable middle-aged and older adults with chronic conditions: A cross-sectional study. Maturitas, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z., Zhao, L., Wei, H., Wang, X., & Riemersma, R. R. (2023). Do guanxi and harmonious leadership matter in the sociocultural integration by Chinese multinational enterprises in The Netherlands? International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(10), 4631–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, J., Skalski, S. B., Sołbut, A., Rutkowski, S., & Konaszewski, K. (2022). Resilience and regulation of emotions in adolescents: Serial mediation analysis through self-esteem and the perceived social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenaeus, F. (2012). Organ transplantation and personal identity: How does loss and change of organs affect the self? Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 37(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svet, M., Portalupi, L. B., Pyszczynski, T., Matlock, D. D., & Allen, L. A. (2023). Applying terror management theory to patients with life-threatening illness: A systematic review. BMC Palliative Care, 22(1), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D. M., Booth, L., Moore, D., & Mathers, J. (2022). Peer support for people with chronic conditions: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, K. E., III, Reed, D. E., Goncy, E. A., Cornelius, T., & Edmondson, D. (2020). Anxiety buffer disruption: Self-evaluation, death anxiety, and stressor appraisals among low and high posttraumatic stress symptom samples. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(5), 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schie, C. C., Chiu, C. D., Rombouts, S., Heiser, W. J., & Elzinga, B. M. (2018). When compliments do not hit but critiques do: An fMRI study into self-esteem and self-knowledge in processing social feedback. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(4), 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-S., Yen, P.-T., Weng, S.-F., Hsu, J.-H., & Yeh, J.-L. (2022). Clinical patterns of traditional Chinese medicine for ischemic heart disease treatment: A population-based cohort study. Medicina, 58(7), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P., Gao, H., Xu, J., Huang, J., & Wang, C. (1998). Reliability and validity study of self-esteem scale. Shandong Psychiatry, 4, 31–32+22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Li, F., Qiao, W., Zhang, J., & Dong, N. (2025). Global challenges and development of heart transplantation: Wuhan Protocol development and clinical implementation. Chinese Medical Journal, 138(13), 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. (1993). SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide, 2. New England Medical Center, Health Institute. [Google Scholar]

- White-Williams, C., Grady, K. L., Fazeli, P., Myers, S., Moneyham, L., Meneses, K., & Rybarczyk, B. (2014). The partial mediation effect of satisfaction with social support and coping effectiveness on health-related quality of life and perceived stress long-term after heart transplantation. Nursing: Research and Reviews, 4, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S., Liu, H., Li, Y., & Teng, Y. (2024). The influence of self-esteem on sociocultural adaptation of college students of Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan: The chain mediating role of social support and school belonging. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S. (1994). Theoretical foundation and research applications of the social support rating scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.-X., Zhang, J., Ye, B.-J., Zheng, X., & Sun, P.-Z. (2012). Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(5), 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., Tian, J., Yang, H., Han, G., Liu, Y., He, H., Han, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The causal effects of anxiety-mediated social support on death in patients with chronic heart failure: A multicenter cohort study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 3287–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Li, Y., Yao, Q., & Wen, X. (2013). The application of the Chinese version of the death anxiety scale and its implications for death education. Journal of Nursing, 28(21), 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano, J., Celano, C. M., Januzzi, J. L., Massey, C. N., Chung, W. J., Millstein, R. A., & Huffman, J. C. (2020). Psychiatric and psychological interventions for depression in patients with heart disease: A scoping review. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(22), e018686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, E., Rimé, B., & Nils, F. (2004). Social sharing of emotion, emotional recovery, and interpersonal aspects. In The regulation of emotion (pp. 157–185). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. (2021). On the paradox of Wuwei—A refutation and defense of Daoist “right action”. Philosophical Trends, 202107(7), 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D., Zhang, N., Chang, H., Shi, Y., Tao, Z., Zhang, X., Miao, Q., & Li, X. (2023). Mediating role of hope between social support and self-management among Chinese liver transplant recipients: A multi-center cross-sectional study. Clinical Nursing Research, 32(4), 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Jin, J., Luo, C., & Chen, A. (2022). Excavating the social representations and perceived barriers of organ donation in China over the past decade: A hybrid text analysis approach. Front Public Health, 10, 998737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. (2025). Exploration and prospects for the high quality development of standardized heart transplantation in China. Chinese Circulation Journal, 40(4), 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Liu, G., Huang, Y., Huang, T., Lin, S., Lan, J., Yang, H., & Lin, R. (2023). The contribution of cultural identity to subjective well-being in collectivist countries: A study in the context of contemporary Chinese culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1170669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | - | - | 1 | ||||||

| 2 Age | 43.860 | 11.276 | −0.009 | 1 | |||||

| 3 Heart transplantation years | 4.380 | 3.326 | 0.087 | 0.048 | 1 | ||||

| 4 Social support | 36.670 | 9.388 | −0.089 | −0.046 | 0.069 | 1 | |||

| 5 Self-esteem | 24.650 | 5.217 | −0.015 | −0.082 | 0.038 | 0.433 *** | 1 | ||

| 6 Death anxiety | 46.580 | 10.444 | 0.097 * | 0.142 ** | −0.089 | −0.362 *** | −0.345 *** | 1 | |

| 7 Quality of life | 48.410 | 17.291 | −0.121 * | −0.112 * | 0.160 ** | 0.417 *** | 0.395 *** | −0.439 *** | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Fitting Indicator | Coefficient Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | R2 | F | β | t |

| Self-esteem | Gender | 0.192 | 24.407 *** | 0.023 | 0.502 |

| Age | −0.062 | −1.388 | |||

| Heart transplantation years | 0.009 | 0.209 | |||

| Social support | 0.432 | 9.653 *** | |||

| Death anxiety | Gender | 0.198 | 20.158 *** | 0.079 | 1.775 |

| Age | 0.116 | 2.616 ** | |||

| Heart transplantation years | −0.076 | −1.697 | |||

| Social support | −0.247 | −4.982 *** | |||

| Self-esteem | −0.225 | −4.562 *** | |||

| Quality of life | Gender | 0.322 | 32.220 *** | −0.084 | −2.030 * |

| Age | −0.055 | −1.318 | |||

| Heart transplantation years | 0.124 | 2.997 ** | |||

| Social support | 0.216 | 4.602 *** | |||

| Self-esteem | 0.200 | 4.297 *** | |||

| Death anxiety | −0.265 | −5.826 *** | |||

| Path | Effect Value | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Relative Mediation Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path1: SS → SE → QoL | 0.086 | 0.021 | 0.046 | 0.130 | 21.9% |

| Path2: SS → DA → QoL | 0.065 | 0.018 | 0.034 | 0.103 | 16.6% |

| Path3: SS → SE → DA → QoL | 0.026 | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.042 | 6.6% |

| Total indirect effect | 0.178 | 0.026 | 0.129 | 0.231 | 45.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Gui, S.; Zhu, L.; Bian, X.; Shen, H.; Jiao, C. Psychosocial Adaptation After Heart Transplantation: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety on Social Support and Quality of Life in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1297. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101297

Gao C, Gui S, Zhu L, Bian X, Shen H, Jiao C. Psychosocial Adaptation After Heart Transplantation: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety on Social Support and Quality of Life in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1297. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101297

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Chan, Song Gui, Lijun Zhu, Xiaoqian Bian, Heyong Shen, and Can Jiao. 2025. "Psychosocial Adaptation After Heart Transplantation: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety on Social Support and Quality of Life in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1297. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101297

APA StyleGao, C., Gui, S., Zhu, L., Bian, X., Shen, H., & Jiao, C. (2025). Psychosocial Adaptation After Heart Transplantation: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Death Anxiety on Social Support and Quality of Life in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1297. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101297