Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Background and Proposed Hypotheses

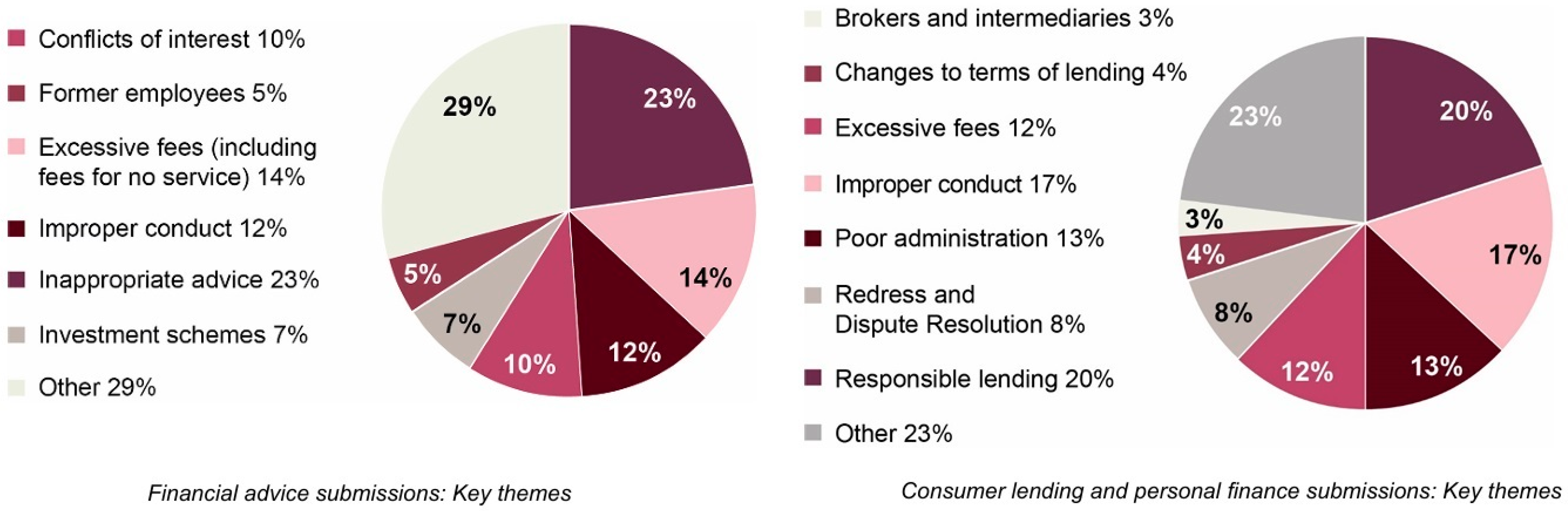

2.1. Financial Vulnerability Among Australian Female Consumers

2.2. Behavioural Biases and Adaptive Market Hypothesis

2.3. Rationality and Financial Decision-Making

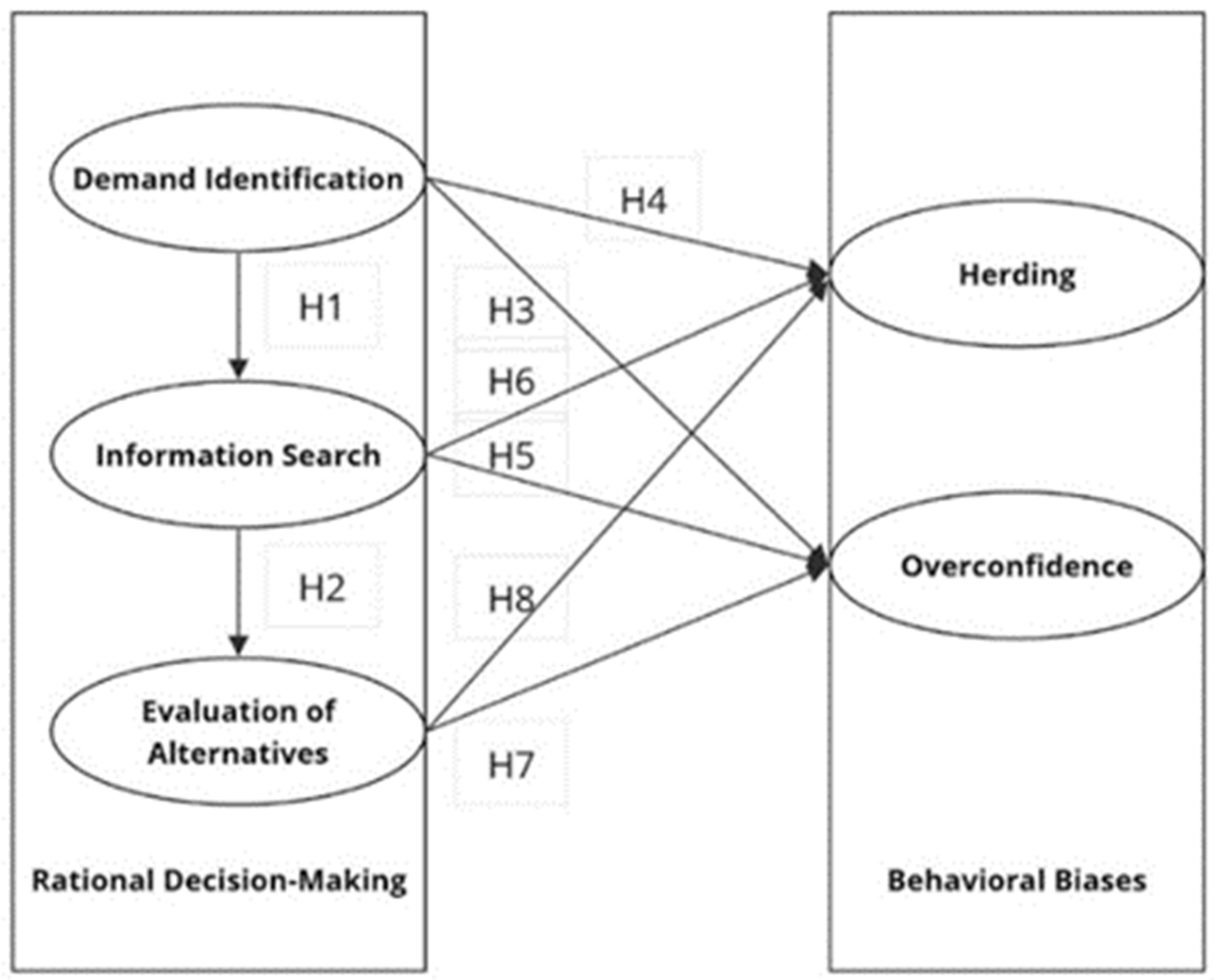

2.4. Rational Decision-Making and Behavioural Biases

2.4.1. Rational Decision-Making and Overconfidence Bias

2.4.2. Rational Decision-Making and Herding Bias

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Survey Administration

3.2. Data Screening

3.3. Sampling

3.4. Adapting SEM Techniques for Data Analysis

3.5. Development of the Survey Instrument

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Responses to Hypothetical Scenarios and Financial Literacy Levels Among Australian Female Consumers

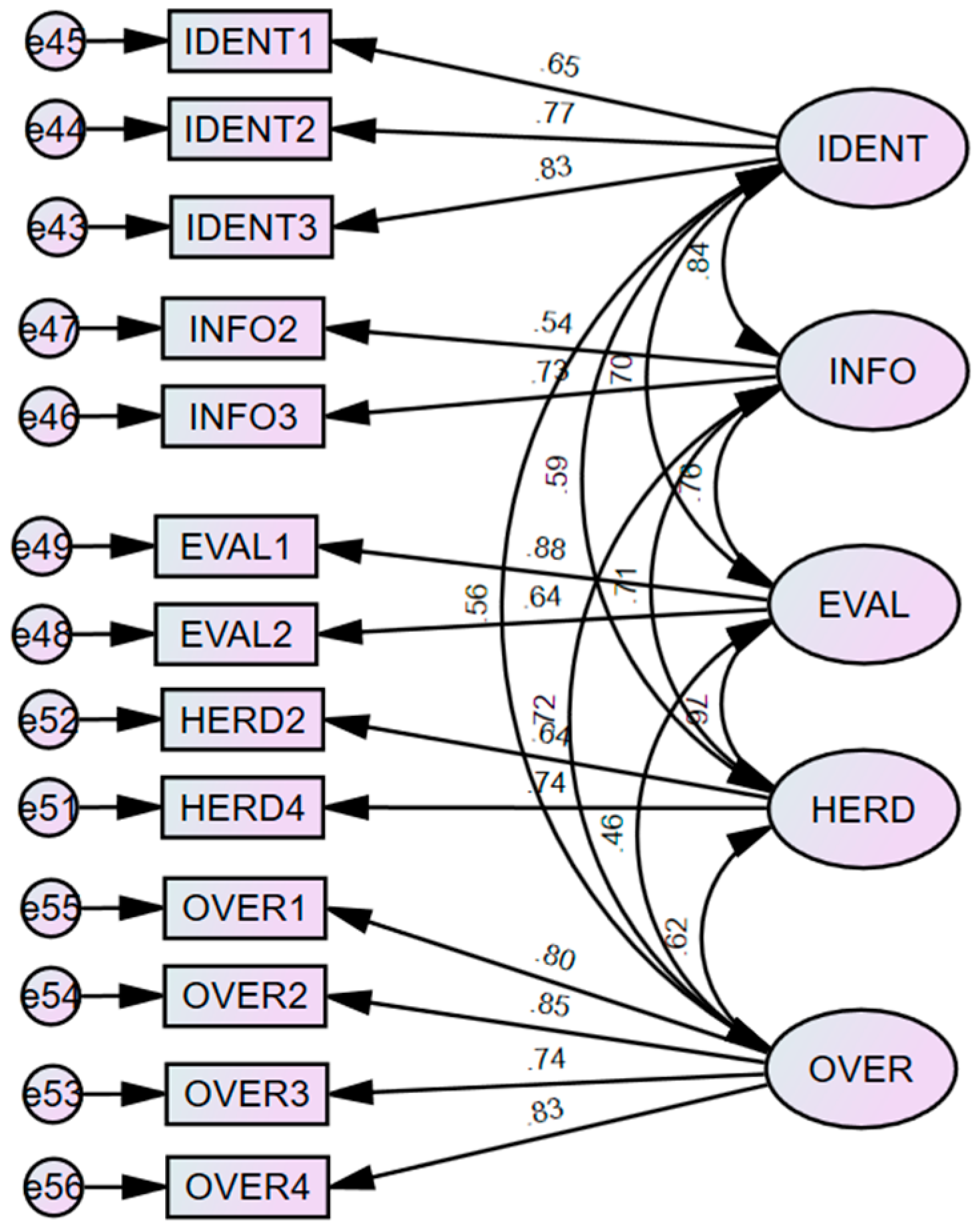

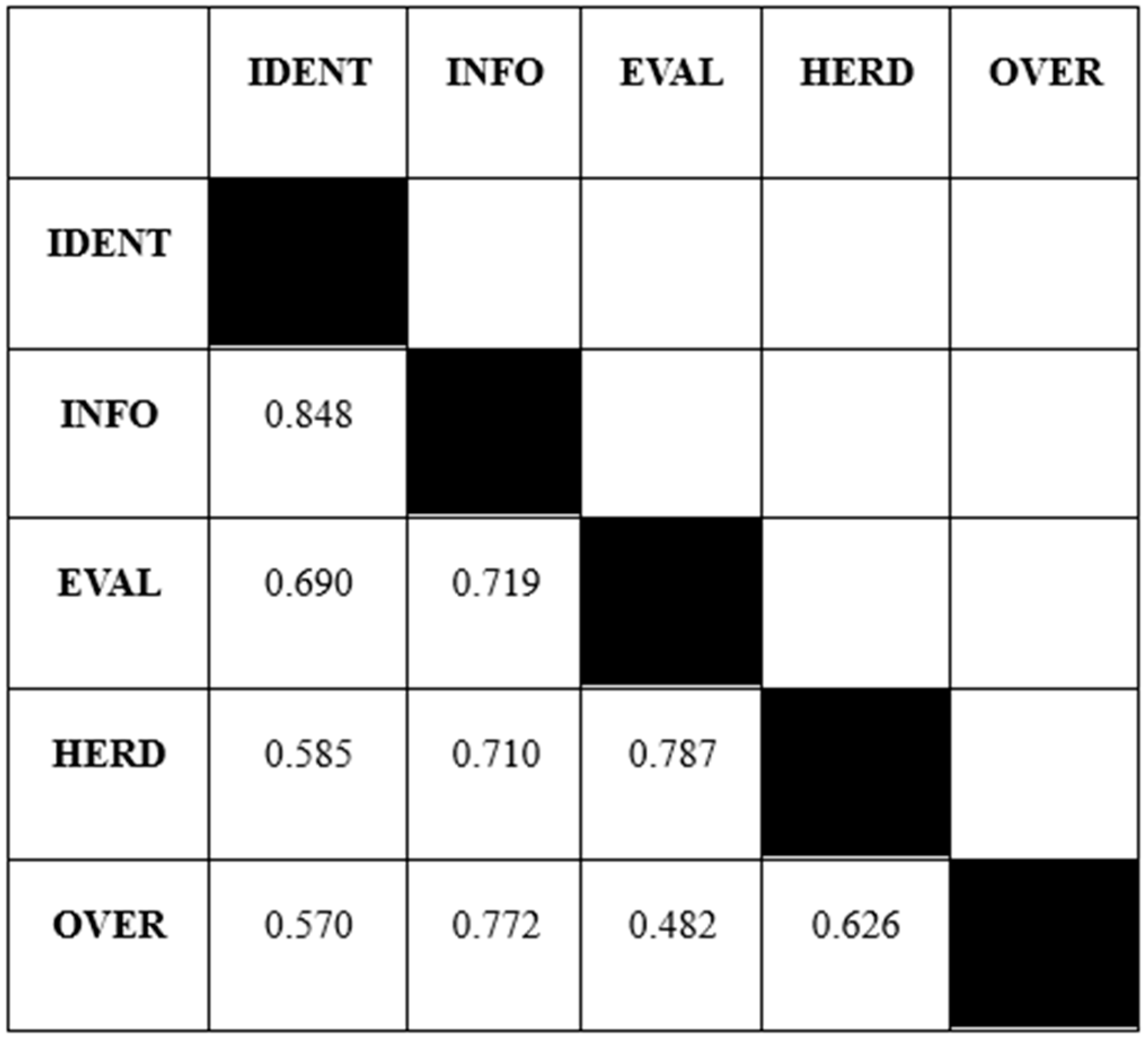

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

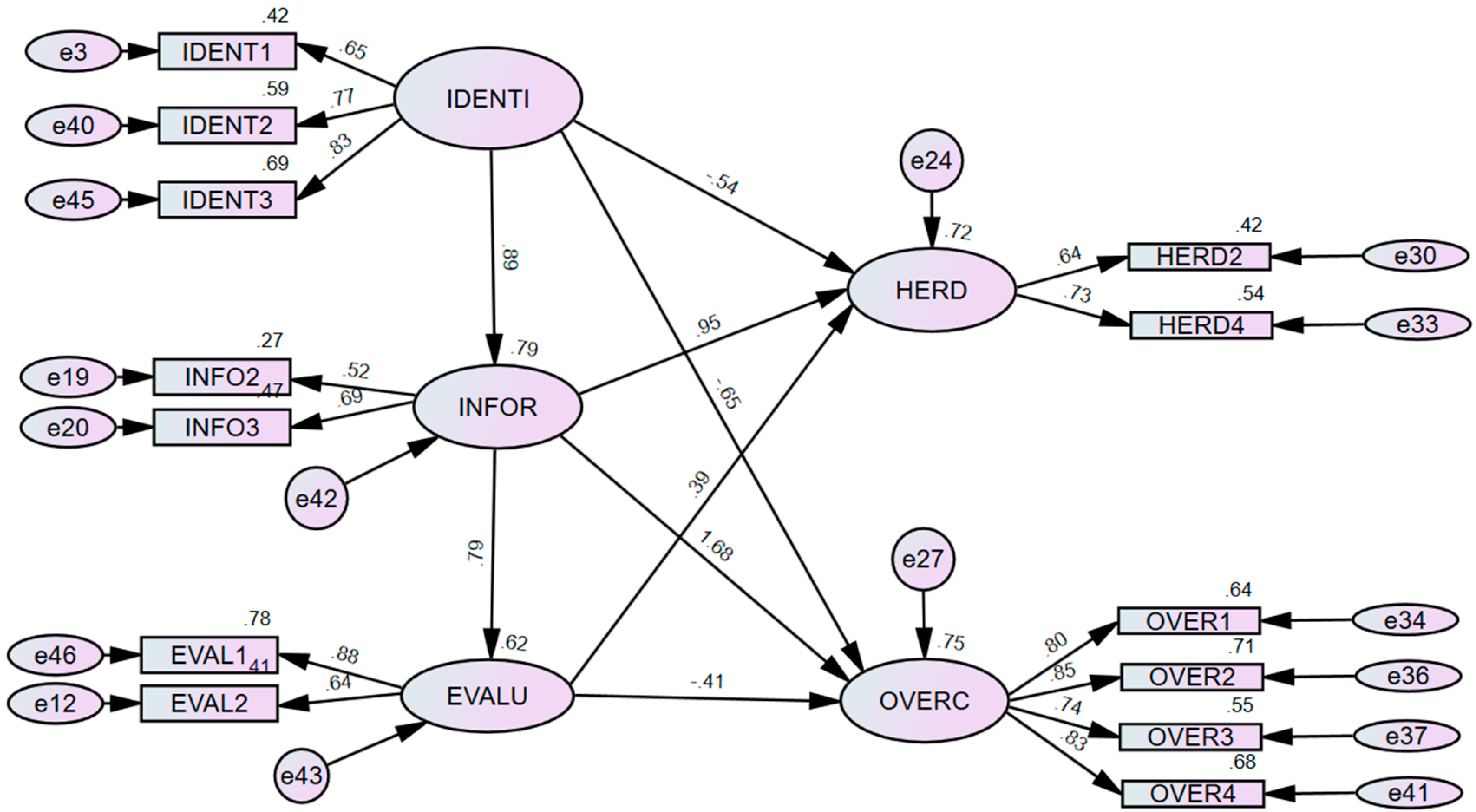

4.3. Results of Structural Equation Modelling

4.4. Role of Demographical Variables on Rational Decision-Making Process

5. Theoretical Contributions

6. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ABS. (2022). Historical poupulation: Population size & growth. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/historical-population/2021#data-downloads (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Adil, M., Singh, Y., & Ansari, M. S. (2021). How financial literacy moderate the association between behaviour biases and investment decision? Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N., Kaye, D., & Odinet, C. (2022). #Fintok and financial regulation. Arizona State Law Journal, 54(4), 1035–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M. I., & Hu, J. (2019). Detecting common method bias: Performance of the harman’s single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 50(2), 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Rind, A., Boubaker, S., & Jarjir, S. L. (2023). Peer effects in financial economics: A literature survey. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. E. (2002). Toward a theory of consumer choice as sociohistorically shaped practical experience: The fits-like-a-glove (FLAG) Framework. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4), 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allianz. (2023). Playing with a squared ball: The financial literacy gender gap. A Research. Available online: https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/publications/specials_fmo/financial-literacy.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Andrade, E. B., & Ariely, D. (2009). The enduring impact of transient emotions on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASIC. (2022). Financial services royal commission. Available online: https://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/financial-services/regulatory-reforms/financial-services-royal-commission/#comms (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Ateş, S., Coşkun, A., Şahin, M. A., & Demircan, M. L. (2016). Impact of financial literacy on the behavioral biases of individual stock investors: Evidence from borsa istanbul. Business & Economics Research Journal, 7(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., Goyal, N., & Gaur, V. (2019). How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioral biases. Managerial Finance, 45(1), 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A. K., & Dulleck, U. (2020). Why do (some) consumers purchase complex financial products? An experimental study on investment in hybrid securities. Economic Analysis and Policy, 67, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, A., Hewer, P., & Howcroft, B. (2000). An exposition of consumer behaviour in the financial services industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 18(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J. R., Luce, M. F., & Payne, J. W. (1998). Constructive consumer choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J. (2013). Consumer behaviour: SAGE publications. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J. P. (2008). Consumer behaviour theory: Approaches and models. Bournemouth University. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnermeier, M., Oehmke, M., & Jel, G. (2009). Complexity in financial markets (p. 8). Working Paper. Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, K. (2005). How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products? Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 10(1), 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, P. B., & Steele, C. M. (2010). Stereotype threat affects financial decision making. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-H., & Lin, S.-J. (2015). The effects of national culture and behavioral pitfalls on investors’ decision-making: Herding behavior in international stock markets. International Review of Economics & Finance, 37, 380–392. [Google Scholar]

- Chui, A. C. W., & Kwok, C. C. Y. (2008). National culture and life insurance consumption. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(1), 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. R. (2016). Effect of fund size on the performance of Australian superannuation funds. Accounting & Finance, 56(3), 695–725. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, F. (2020). Rationalization is rational. Behavioral Brain Sciences, 43, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daruvala, D. (2007). Gender, risk and stereotypes. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 35(3), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maesschalck, R., Jouan-Rimbaud, D., & Massart, D. (2000). The mahalanobis distance, chemometrics and intelligent laboratory systems. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 50, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Cardoso, N., Zorgi Salvador, E., Broch, G., Mette, F. M. B., Yoshinaga, C. E., & de Lara Machado, W. (2023). Measuring behavioral biases in individual investors decision-making and sociodemographic correlations: A systematic review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 16(4), 636–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desigan, C. G., Kalaiselvi, S., & Anusuya, L. (2006). Women investors’ perception towards investment—An empirical study. Indian Journal of Marketing, 36(4), 14–37. [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno, D., Petty, R. E., Wegener, D. T., & Rucker, D. D. (2000). Beyond valence in the perception of likelihood: The role of emotion specificity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(3), 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devenow, A., & Welch, I. (1996). Rational herding in financial economics. European Economic Review, 40(3–5), 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. F. (1998). Adding value to service offerings: The case of UK retail financial services. European Journal of Marketing, 32(11), 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibb, S., Merendino, A., Aslam, H., Appleyard, L., & Brambley, W. (2021). Whose rationality? Muddling through the messy emotional reality of financial decision-making. Journal of Business Research, 131, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, T., Brimble, M., Freudenberg, B., & Hunt, K. H. M. (2018). Insurance literacy in Australia: Not knowing the value of personal insurance. Financial Planning Research Journal, 4(1), 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dureha, S., & Jain, V. (2022). An empirical study on the relationship between financial literacy and emotional biases. Cardiometry, (23), 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, L., Fry, T. R. L., & Risse, L. (2016). The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frau, M., Cabiddu, F., Frigau, L., Tomczyk, P., & Mola, F. (2023). How emotions impact the interactive value formation process during problematic social media interactions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(5), 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrebøe, E. F., & Nyhus, E. K. (2022). Financial self-efficacy, financial literacy, and gender: A review. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 56(2), 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galariotis, E. C., Rong, W., & Spyrou, S. I. (2015). Herding on fundamental information: A comparative study. Journal of Banking Finance, 50, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallery, N., Newton, C., & Palm, C. (2011). Framework for assessing financial literacy and superannuation investment choice decisions. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 5(2), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetti, E., & Giusberti, F. (2012). The effect of anger and anxiety traits on investment decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(6), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazani, M. M., & Araghi, M. K. (2014). Evaluation of the adaptive market hypothesis as an evolutionary perspective on market efficiency: Evidence from the Tehran stock exchange. Research in International Business and Finance, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. M. (1999). Fast and frugal heuristics: The adaptive toolbox. In Simple heuristics that make us smart (pp. 3–34). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2021). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grežo, M. (2021). Overconfidence and financial decision-making: A meta-analysis. Review of Behavioral Finance, 13(3), 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, A., Hübler, O., Kouwenberg, R., & Menkhoff, L. (2016). Financial literacy: Thai middle class women do not lag behind. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 31, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson, S., Minelgaite, I., Kristinsson, K., & Pálsdóttir, S. (2022). Financial literacy and gender differences: Women choose people while men choose things? Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P., & Goyal, P. (2024). Herding the influencers for investment decisions: Millennials bust the gender stereotype. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (Vol. 7). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 5). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K. (2009). Consumer decision making in low-income families: The case of conflict avoidance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 8(5), 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. C. (2021). The impact of anthropomorphism on consumers’ purchase decision in chatbot commerce. Journal of Internet Commerce, 20(1), 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2007). Feelings and consumer decision making: The appraisal-tendency framework. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(3), 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T. (2016). Financial literacy and the limits of financial decision-making. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne, K. (2019). Royal commission into misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry. Commonwealth of Australia. Available online: https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-09/fsrc-volume-3-final-report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, M. A., Hogarth, J. M., & Beverly, S. G. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin HeinOnline, 89, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, T. K., & Loibl, C. (2008). Gender differences in investment behavior. In Handbook of consumer finance research (pp. 253–270). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, T. K., & Mugenda, O. (2000). Gender differences in financial perceptions, behaviors and satisfaction. Journal of Financial Planning, 13(2), 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hirdinis, M. (2021). Does Herding behaviour and overconfidence drive the investor’s decision making during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(8), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G. C. (1974). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Howcroft, B., Hewer, P., & Hamilton, R. (2003). Consumer decision-making styles and the purchase of financial services. Service Industries Journal, 23(3), 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-L., Chen, H.-L., Huang, P.-K., & Lin, W.-Y. (2021). Does financial literacy mitigate gender differences in investment behavioral bias? Finance Research Letters, 41, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubley, A. M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2011). Validity and the consequences of test interpretation and use. Social Indicators Research, 103(2), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inghelbrecht, K., & Tedde, M. (2024). Overconfidence, financial literacy and excessive trading. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 219, 152–195. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, N., Jain, V., Li, Z., Sattar, J., & Tongkachok, K. (2022). Post-COVID-19 investor psychology and individual investment decision: A moderating role of information availability. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 846088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, F. H., Barry, J. B., Rolph, E. A., & Rolph, E. A. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Juurikkala, O. (2012). The behavioral paradox: Why investor irrationality calls for lighter and simpler financial regulation. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 18, 33–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58(9), 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Slovic, S. P., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M., & Vohra, T. (2012). Women and stock market participation: A review of empirical evidences. Management and Labour Studies, 37(4), 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keneley, M. J. (2020). The shifting corporate culture in the financial services industry: Explaining the emergence of the ‘culture of greed’in an Australian Financial Services Company. Business History, 65(4), 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, T., & Kapoor, S. (2024). Behavioral biases and the rational decision-making process of financial professionals: Significant factors that determine the future of the financial market. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 21(1), 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, S. U., & Krishnamurthy, S. (2007). An analysis of consumer power on the Internet. Technovation, 27(1–2), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J., & Prince, N. (2023). Overconfidence bias in investment decisions: A systematic mapping of literature and future research topics. FIIB Business Review, 23197145231174344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Goyal, N. (2016). Evidence on rationality and behavioural biases in investment decision making. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Rao, S., Goyal, K., & Goyal, N. (2022). Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance: A bibliometric overview. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 34, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L. I., vor dem Esche, J., Mathwick, C., Novak, T. P., & Hofacker, C. F. (2013). Consumer power: Evolution in the digital age. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27(4), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, P., Visalakshmi, S., Thamaraiselvan, N., & Senthilarasu, B. (2013). Assessing the linkage of behavioural traits and investment decisions using SEM approach. International Journal of Economics & Management, 7(2), 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, L. W. (2012). Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebdaoui, H., Chetioui, Y., & Guechi, E. (2021). The impact of behavioral biases on investment performance: Does financial literacy matter. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 11(3), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P. D., Ormrod, J. E., & Johnson, L. R. (2014). Practical research: Planning and design. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Lehdonvirta, V., Oksanen, A., Räsänen, P., & Blank, G. (2021). Social media, web, and panel surveys: Using non-probability samples in social and policy research. Policy & Internet, 13(1), 134–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S. I., & So, A. S. I. (2021). Online teaching and learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic—A comparison of teacher and student perceptions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 33(3), 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., Small, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2004). Heart strings and purse strings: Carryover effects of emotions on economic decisions. Psychological Science, 15(5), 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C., Klein, O., Dominicy, Y., & Ley, C. (2018). Detecting multivariate outliers: Use a robust variant of the Mahalanobis distance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-W. (2011). Elucidating Rational investment decisions and behavioral biases: Evidence from the taiwanese stock market. African Journal of Business Management, 5(5), 1630–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Litimi, H. (2017). Herd behavior in the French stock market. Review of Accounting and Finance, 16(4), 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A. W. (2005). Reconciling efficient markets with behavioral finance: The adaptive markets hypothesis. Journal of Investment Consulting, 7(2), 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A. W. (2019). The adaptive markets hypothesis: Market efficiency from an evolutionary perspective (Vol. 30). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loibl, C., & Hira, T. K. (2006). A workplace and gender-related perspective on financial planning information sources and knowledge outcomes. Financial Services Review, 15(1), 21. [Google Scholar]

- Loibl, C., Lee, J., Fox, J., & Mentel-Gaeta, E. (2007). Women’s high-consequence decision making: A nonstatic and complex choice process. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 18(2), 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A., & Garza, R. (2023). Consumer bias against evaluations received by artificial intelligence: The mediation effect of lack of transparency anxiety. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(6), 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Otálora, M., & Alkire, L. (2019). Investigating the transformative impact of bank transparency on consumers’ financial well-being. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(4), 1062–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, A., Barbić, D., & Uzelac, M. (2023). Theoretical underpinnings of consumers’ financial capability research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(1), 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (2008). Household saving behavior: The role of financial literacy, information, and financial education programs (pp. 1–43). NBER Working Paper Series. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w13824 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: How do women fare? American Economic Review, 98(2), 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchelli, O. S. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education. Business Economics, 42(1), 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, L., & Sabadoz, C. (2015). Rethinking the concept of consumer empowerment: Recognizing consumers as citizens. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(5), 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S. C., Lalwani, A. K., & Ping, L. (2001). Reference group influence and perceived risk in services among working women in Singapore: A replication and extension. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 14(1), 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melović, B., Veljković, S. M., Ćirović, D., Vulić, T. B., & Dabić, M. (2022). Entrepreneurial decision-making perspectives in transition economies–tendencies towards risky/rational decision-making. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18(4), 1739–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H., Raisinghani, D., & Theoret, A. (1976). The structure of “unstructured” decision processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 246–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireku, K., Appiah, F., & Agana, J. A. (2023). Is there a link between financial literacy and financial behaviour? Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2188712. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, M. M., Sulaiman, N. L., Sern, L. C., & Salleh, K. M. (2015). Measuring the validity and reliability of research instruments. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 204, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushinada, V. N. C. (2020). Are individual investors irrational or adaptive to market dynamics? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 25, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M., Farah, M. F., & Hasni, M. J. S. (2021). The transformative role of firm information transparency in triggering retail investor’s perceived financial well-being. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(7), 1091–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculaescu, C. E., Sangiorgi, I., & Bell, A. R. (2023). Does personal experience with COVID-19 impact investment decisions? Evidence from a survey of US retail investors. International Review of Financial Analysis, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J. R. (2005). Social mood and financial economics. The Journal of Behavioral Finance, 6(3), 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J. R., & Sias, R. W. (1999). Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. The Journal of Finance, 54(6), 2263–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J. (2019). “Because they could”: Trust, Integrity, and purpose in the regulation of corporate governance in the aftermath of the royal commission into misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry. Law & Financial Markets Review, 13(2–3), 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. W., & Overbay, A. (2004). The power of outliers (and why researchers should always check for them). Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 9(1), 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ozmete, E., & Hira, T. (2011). Conceptual analysis of behavioral theories/models: Application to financial behavior. European Journal of Social Sciences, 18(3), 386–404. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L., Nicholls, A. R., Clough, P. J., & Crust, L. (2015). Assessing model fit: Caveats and recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation modeling. Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science, 19(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousttchi, K., & Dehnert, M. (2018). Exploring the digitalization impact on consumer decision-making in retail banking. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A. (2020). Financial literacy in Australia: Insights from HILDA data. UWA Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, A., & Wright, R. E. (2023). Gender, financial literacy and pension savings. Economic Record, 99(324), 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A., Qiu, L., & Wright, R. E. (2023). Understanding the gender gap in financial literacy: The role of culture. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 58(1), 146–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A. C., & Wright, R. E. (2019). Understanding the gender gap in financial literacy: Evidence from Australia. Economic Record, 95(S1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R. (2021). An exploratory study on the impact of the COVID-19 confinement on the financial behavior of individual investors. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 16(3), 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rezabakhsh, B., Bornemann, D., Hansen, U., & Schrader, U. (2006). Consumer power: A comparison of the old economy and the internet economy. Journal of Consumer Policy, 29(1), 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, H. (2001). Do consumers know what they want? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(5), 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubesam, A., & Júnior, G. d. S. R. (2022). COVID-19 and herding in global equity markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 35, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, S. K., Arora, A. P., & Dhameja, N. (2013). An exploratory inquiry into the psychological biases in financial investment behavior. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 14(2), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. (2000). Rational Choice Theory. In Understanding contemporary society: Theories of the present (pp. 126–138). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Servon, L. J., & Kaestner, R. (2008). Consumer financial literacy and the impact of online banking on the financial behavior of lower-income bank customers. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 42(2), 271–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., Alshurideh, M., Al-Dmour, A., & Al-Dmour, R. (2021). Understanding the influences of cognitive biases on financial decision making during normal and COVID-19 pandemic situation in the United Arab Emirates. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Business Intelligence, 334, 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A., Hewege, C., & Perera, C. (2022). Violations of CSR practices in the Australian financial industry: How is the decision-making power of Australian women implicated? Sustainability, 15(1), 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Hewege, C., & Perera, C. (2023). How do Australian female consumers exercise their decision-making power when making financial product decisions? The triad of financial market manipulation, rationality and emotions. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 41(6), 1464–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., & Firoz, M. (2022). Delineating investors’ rationality and behavioural biases-evidence from the Indian stock market. International Journal of Management Practice, 15(1), 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, S. S., & Seiling, S. B. (2004). Moving into action: Application of the transtheoretical model of behavior change to financial education. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 15(1), 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. (1970). Administrative behavior: Study of decision-making process. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. A. (1997). Models of bounded rationality: Empirically grounded economic reason (Vol. 3). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnewe, E., & Nicholson, G. (2023). Healthy financial habits in young adults: An exploratory study of the relationship between subjective financial literacy, engagement with finances, and financial decision-making. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 564–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M., Russell-Bennett, R., & Previte, J. (2012). Consumer behaviour. Pearson Higher Education AU. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos, V., & d’Astous, A. (2013). Attitudinal, self-efficacy, and social norms determinants of young consumers’ propensity to overspend on credit cards. Journal of Consumer Policy, 36(2), 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N. M., & Suki, N. M. (2017). Modeling the determinants of consumers’ attitudes toward online group buying: Do risks and trusts matters? Journal of Retailing Consumer Services, 36, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, G. (2024). Impact of financial literacy and behavioural biases on investment decision-making. FIIB Business Review, 13(1), 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1989). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. In Multiple criteria decision making and risk analysis using microcomputers (pp. 81–126). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, A., & Hudson, R. (2013). Efficient or adaptive markets? Evidence from major stock markets using very long run historic data. International Review of Financial Analysis, 28, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Selm, M., & Jankowski, N. W. (2006). Conducting online surveys. Quality and Quantity, 40, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay Kumar, V., & Senthil Kumar, J. (2023). Insights on financial literacy: A bibliometric analysis. Managerial Finance, 49(7), 1169–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T., Butler, D., & Smith, L. (2023). Sludged! Can financial literacy shield against price manipulation at the shops? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(5), 1853–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A. C. (2013). Financial literacy and financial literacy programmes in Australia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 18(3), 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A. C., & West, T. (2021). Financial literacy and financial education in Australia and New Zealand. In The Routledge handbook of financial literacy (pp. 454–469). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L. T., Harrison, T., Waite, K., & Hunter, G. L. (2006). The internet, information and empowerment. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9), 972–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J. (2016). Handbook of consumer finance research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. J., O’Neill, B., Prochaska, J. M., Kerbel, C., Brennan, P., & Bristow, B. (2001). Application of the transtheoretical model of change to financial behavior. Consumer Interests Annual, 47(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, T.-m., & Ling, Y. (2022). Confidence in financial literacy, stock market participation, and retirement planning. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43(1), 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahera, S. A., & Bansal, R. (2018). Do investors exhibit behavioral biases in investment decision making? A systematic review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(2), 210–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Psychological Theories/Models | Key Literature | Implications in Women’s Financial Decision-Making Styles |

|---|---|---|

| Theory of planned behaviour | Sotiropoulos and d’Astous (2013) | Social class and comparison among women are observed based on excessive spending using credit cards. |

| The transtheoretical model of change | Shockey and Seiling (2004); Xiao et al. (2001) | Women tend to hold on to their investments to gain a larger profit rather than selling them, even if selling might be more profitable. |

| Health-belief model | Kaur and Vohra (2012) | Most female buyers have a sense of fear/loss when making decisions. |

| Theory of reasoned action | Ozmete and Hira (2011) | Women perceive financial decision-making as traumatic and time-consuming. |

| Risk-reduction model | Kaur and Vohra (2012); Ozmete and Hira (2011) | Women rely on financial advisors so as to minimise risk while making decisions. |

| Role theory | Hira and Mugenda (2000); Loibl and Hira (2006) | Less financial knowledge leads to a lower level of confidence in the decision-making process. |

| Hypothetical Scenario 1 | Low Gain/No Loss | Medium Gain/Medium Loss | High Gain/High Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypo 1: Assume that your bank offers you an investment with the following characteristics: low gain/no loss, medium gain/medium loss and high gain/high loss. Which one would you choose? | 47.33% | 50.70% | 1.96% |

| Hypothetical Scenario 2 | Will shift to other investment products that have better performance | Will wait for some days to see any improvements in performance | Will wait for some weeks to see any improvements in performance |

| Hypo 2: Assume that you have invested some money in investment products. What do you do if their interest rates start to generate a loss? | 24.64% | 54.06% | 21.28% |

| Hypothetical Scenario 3 | Will shift to an investment with a stable return | Will wait for some days to see a stable interest rate | Will wait for some weeks to see a stable interest rate |

| Hypo 3: Assume that you have invested in some investment products. What do you do if their interest rates start to have an unexpectedly high return? | 16.80% | 55.46% | 27.73% |

| Forecasting Investment Trends | Cannot Predict (1) | Can Predict (10) | |

| How easy is it for you to predict the interest rates of the financial product that you have purchased recently? | 80.4% | 19.6% |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | Sig | Cronbach’s (α) | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand Identification | IDENT1 | 0.65 | *** | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.57 |

| IDENT2 | 0.77 | *** | ||||

| IDENT3 | 0.83 | *** | ||||

| Information Search | INFO2 | 0.54 | *** | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.41 |

| INFO3 | 0.73 | *** | ||||

| Evaluation of Alternatives | EVAL1 | 0.88 | *** | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.60 |

| EVAL2 | 0.64 | *** | ||||

| Herding | HERD2 | 0.64 | *** | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.48 |

| HERD4 | 0.74 | *** | ||||

| Overconfidence | OVER1 | 0.80 | *** | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

| OVER2 | 0.85 | *** | ||||

| OVER3 | 0.74 | *** | ||||

| OVER4 | 0.83 | *** |

| Hypothesis | Structural Relationships | Regression Weights | S.E. | C.R. | p Label | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Demand Identification → Information Search | 0.89 | 0.11 | 8.06 | (***) | Supported |

| H2 | Information Search → Evaluation of Alternatives | 0.79 | 0.11 | 8.69 | (***) | Supported |

| H3 | Demand Identification → Overconfidence | −0.65 | 0.41 | −2.07 | (***) | Supported |

| H4 | Demand Identification → Herding | −0.54 | 0.15 | −2.45 | (***) | Supported |

| H5 | Information Search → Overconfidence | 1.68 | 0.51 | 4.20 | (***) | Supported |

| H6 | Information Search → Herding | 0.95 | 0.16 | 3.87 | (***) | Supported |

| H7 | Evaluation of Alternatives → Overconfidence | −0.41 | 0.17 | −2.39 | (***) | Supported |

| H8 | Evaluation of Alternatives → Herding | 0.39 | 0.75 | 2.90 | (***) | Supported |

| Structural Relationships of Demographical Variables | Regression Weights | S.E. | C.R. | p Label | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education → Demand Identification | 0.13 | 0.03 | 2.30 | (***) | Supported |

| Education → Information Search | 0.14 | 0.03 | 2.41 | (***) | Supported |

| Education → Evaluation of Alternatives | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.79 | 0.42 | Not Supported |

| Income → Demand Identification | 0.30 | 0.03 | 5.0 | (***) | Supported |

| Income → Information Search | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.39 | 0.164 | Not Supported |

| Income → Evaluation of Alternatives | −0.07 | 0.44 | −1.12 | 0.26 | Not Supported |

| Age → Demand Identification | −0.10 | 0.03 | −1.80 | 0.07 | Not Supported |

| Age → Information Search | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.66 | Not Supported |

| Age → Evaluation of Alternatives | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.32 | 0.75 | Not Supported |

| Marital Status → Demand Identification | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.57 | Not Supported |

| Marital Status → Information Search | −0.15 | 0.03 | −2.70 | (***) | Supported |

| Marital Status → Evaluation of Alternatives | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.31 | Not Supported |

| Key Issues | Institutional/Managerial Implications |

|---|---|

| Marketing Stimuli |

|

| Mechanisms |

|

| Government/Institutional |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, A.; Hewege, C.; Perera, C. Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010058

Sharma A, Hewege C, Perera C. Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Abhishek, Chandana Hewege, and Chamila Perera. 2025. "Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010058

APA StyleSharma, A., Hewege, C., & Perera, C. (2025). Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010058