The Interplay of Structuring and Controlling Teaching Styles in Physical Education and Its Impact on Students’ Motivation and Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Students’ Engagement in PE

1.2. Self-Determination Theory: A Key Perspective to Gain Understanding of the PE Setting

1.3. The Circumplex Approach and the Role of Teaching Styles in PE

1.4. The Merits of a Person-Centered Approach to Better Understand the Coexistence of Structure and Control

1.5. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

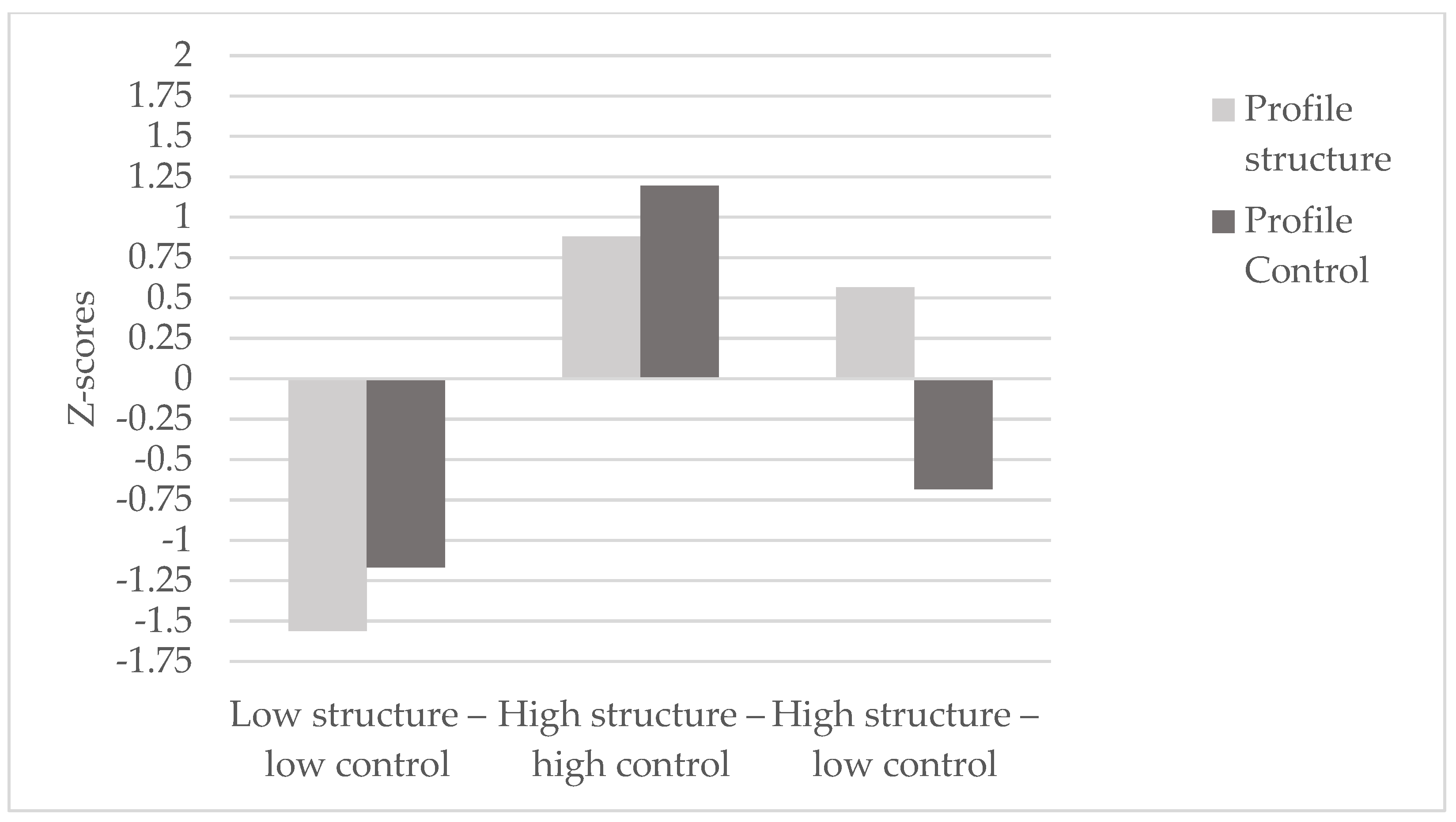

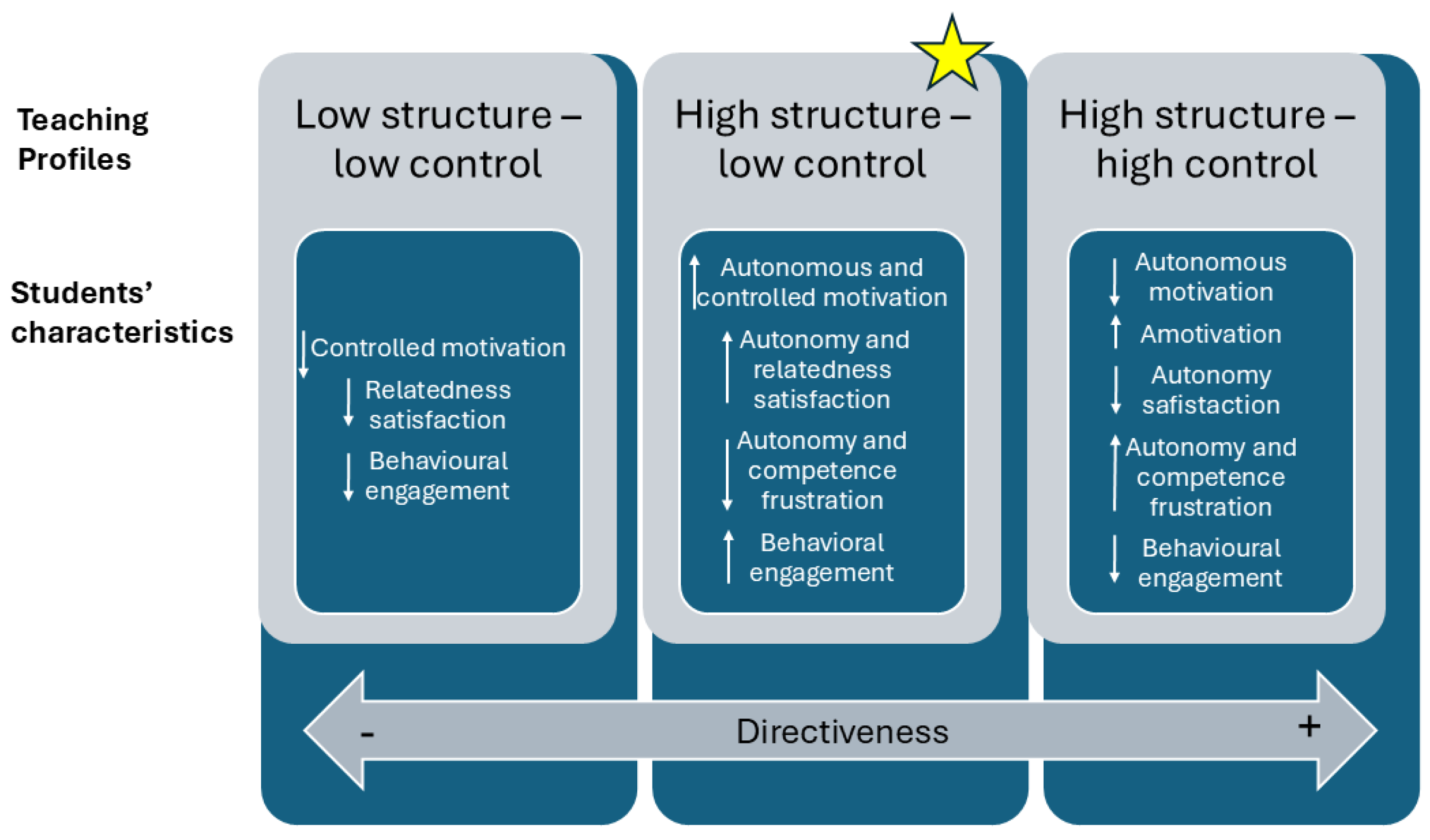

3.2. Teaching Profiles According to Teachers’ Directiveness

3.3. Differences in Students’ Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Teaching Profiles of Highly Directive Teachers

4.2. Differences in Student Outcomes and Engagement According to Teacher Profile

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Cutre, D. Estrategias didácticas y motivacionales en las clases de educación física desde la teoría de la autodeterminación. E-Motion Rev. Educ. Mot. Investig. 2017, 8, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, C.; Skinner, E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H.; Carrell, D.; Jeon, S.; Barch, J. Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 2004, 28, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Kindermann, T.A.; Connell, J.P.; Wellborn, J.G. Engagement and disaffection as organizational constructs in the dynamics of motivational development. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, K.R., Miele, D.B., Eds.; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, L.; Reeve, J.; Herrera, D.; Claux, M. Students’ Agentic Engagement Predicts Longitudinal Increases in Perceived Autonomy-Supportive Teaching: The Squeaky Wheel Gets the Grease. J. Exp. Educ. 2018, 86, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Tseng, C.-M. Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Van Keer, H.; Van den Berghe, L.; De Meyer, J.; Haerens, L. Students’s objectively measured physical activity levels and engagement as a function of between-class and between-student differences in motivation toward physical education. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, T.; Standage, M. Psychological needs and the quality of student engagement in Physical Education: Teachers as key facilitators. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Noetel, M.; Parker, P.D.; Ryan, R.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Reeve, J.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Dicke, T.; Yeung, A.; Ahmadi, M.; et al. A Classification System for Teachers’ Motivational Behaviours Recommended in Self-Determination Theory Interventions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 115, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abós, Á.; Sevil, J.; Martín-Albo, J.; Aibar, A.; García-González, L. Validation Evidence of the Motivation for Teaching Scale in Secondary Education. Span. J. Psychol. 2018, 21, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, E.; Coterón, J.; Gómez, V.; Spray, C.M. A person-centred approach to understanding dark-side antecedents and students’ outcomes associated with physical education teachers’ motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 57, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarripa, J.; Rodríguez-Medellín, R.; Otero-Saborido, F. Basic Psychological Needs, Motivation, Engagement, and Disaffection in Mexican Students during Physical Education Classes. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2022, 41, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Haerens, L.; Soenens, B.; Fontaine, J.R.J.; Reeve, J. Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delrue, J.; Reynders, B.; Broek, G.V.; Aelterman, N.; De Backer, M.; Decroos, S.; De Muynck, G.-J.; Fontaine, J.; Fransen, K.; van Puyenbroeck, S.; et al. Adopting a helicopter-perspective towards motivating and demotivating coaching: A circumplex approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 40, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Lau, S. Complementary roles of care and behavioral control in classroom management: The self-determination theory perspective. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 34, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, A.; Vasconcellos, D.; Cinelli, R.; Hilland, T.; Owen, K.B.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future direction. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriva-Boulley, G.; Haerens, L.; Tessier, D.; Sarrazin, P. Antecedents of primary school teachers’ need-supportive and need-thwarting styles in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R.; García-González, L.; Abós, Á.; Sevil-Serrano, J. Students’ motivational experiences across profiles of perceived need-supportive and need-thwarting teaching behaviors in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2024, 29, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; de Meester, A.; Delrue, J.; Tallir, I.B.; Vande Broek, G.; Goris, W.; Aelterman, N. Different combinations of perceived autonomy support and control: Identifying the most optimal motivating style. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; López-Gajardo, M.A.; Mouratidis, A. See the forest by looking at the trees: Physical education teachers’ interpersonal style profiles and students’ engagement. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.C.; Li, W.; Shen, B. Learning in Physical Education: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, J.; Soenens, B.; Aelterman, N.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Haerens, L. The different faces of controlling teaching: Implications of a distinction between externally and internally controlling teaching for students’ motivation in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, J.; Tallir, I.B.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; Van den Berghe, L.; Speleers, L.; Haerens, L. Does observed controlling teaching behavior relate to students’ motivation in physical education? J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L.R.; Andersson, H. The Person and the Variable in Developmental Psychology. Z. Psychol./J. Psychol. 2010, 218, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R.; Abós, A.; Sevil-Serrano, J.; Haerens, L.; De Cocker, K.; García-González, L. A Circumplex Approach to (de)motivating Styles in Physical Education: Situations-In-School–Physical Education Questionnaire in Spanish Students, Pre-Service, and In-Service Teachers. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 28, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A.; et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarripa, J.; Rodríguez-Medellín, R.; Pérez-Garcia, J.A.; Otero-Saborido, F.; Delgado, M. Mexican Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale in Physical Education. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferriz, R.; González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, A. Revision of the Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC) to include the measure of integrated regulation in physical education. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2015, 24, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Goudas, M.; Biddle, S.; Fox, K. Perceived locus of causality, goal orientations, and perceived competence in school physical education classes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 64, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.; Rodgers, W.; Loitz, C.C.; Scime, G. “It’s who I am... Really!” The importance of integrated regulation in exercise contexts. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2006, 11, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J.; Fahlman, M.; Garn, A. Urban high-school girls’ sense of relatedness and their engagement in Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2012, 31, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Fernández-Bustos, J.G. Adaptación y validación de la escala de compromiso agéntico al contexto educativo español. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2016, 33, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct; Amended 3 August 2016; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. In Psychometric Theory; Nunnally, J.C., Bernstein, I.H., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, L.; Haerens, L.; Abós, Á.; Sevil-Serrano, J.; Burgueño, R. Is high teacher directiveness always negative? Associations with students’ motivational outcomes in physical education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, N. The role of practicum supervisors in behaviour management education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzius, M.; Kirch, A.; Spengler, S.; Blaschke, S.; Mess, F. What makes a physical education teacher? Personal characteristics for physical education development. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 1249–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, M.; López, E. Clima motivacional, razones para la disciplina y comportamiento en Educación Física. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte/Int. J. Med. Sci. Phys. Act. Sport 2012, 12, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.T.; Selman, R.L.; Dishion, T.J.; Stormshak, E.A. A tobit regression analysis of the covariation between middle school students’ perceived school climate and behavioral problems. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Rota, C.; Diloy-Peña, S.; García-Cazorla, J.; Abós, Á.; García-González, L. Las conductas motivacionales docentes en educación física desde la óptica del modelo circular: Efectos sobre el lado oscuro de la motivación del alumnado. Rev. Esp. Educ. Física Deportes 2022, 463, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Peño, A.; Franco, E.; Coterón, J. Do Observed Teaching Behaviors Relate to Students’ Engagement in Physical Education? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doren, N.; De Cocker, K.; Flamant, N.; Compernolle, S.; Vanderlinde, R.; Haerens, L. Observing physical education teachers’ need-supportive and need-thwarting styles using a circumplex approach: How does it relate to student outcomes? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraoka, E.; Kirk, D. Exploring physical education teachers’ awareness of observed teaching behaviour within pedagogies of affect. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2022, 29, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R.; Medina-Casaubón, J. Validity and reliability of the interpersonal behaviors questionnaire in physical education with Spanish secondary school students. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2021, 128, 522–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coterón, J.; Franco, E.; Pérez-Tejero, J.; Sampedro, J. Clima motivacional, competencia percibida, compromiso y ansiedad en educación física. Diferencias en función de la obligatoriedad de la enseñanza. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2013, 22, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, P.; Agbuga, B.; Liu, J.; McBride, R.E. Relatedness Need Satisfaction, Intrinsic Motivation, and Engagement in Secondary School Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Shin, S.H. How teachers can support students’ agentic engagement. Theory Into Pract. 2020, 59, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cazorla, J.; García-González, L.; Burgueño, R.; Diloy-Peña, S.; Abós, Á. What factors are associated with physical education teachers’ (de)motivating teaching style? A circumplex approach. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2024, 1356336X241248262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Arias, A.; Harvey, S.; García-Herreros, F.; González-Villora, S.; Práxedes, A.; Moreno, A. Effect of a hybrid teching games for understanding/sport education unit on elementary students’ self-determined motivation in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Casaubón, J.; Burgueño, R. Influence of a sport education season on motivational strategies in hih school students: A self-determination theory-based perspective. E-Balonmano Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Mosston, M.; Ashworth, S. Teaching Physical Education, 1st online ed.; Spectrum Institute for Teaching and Learning: Port St. Lucie, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Soenens, B.; Aelterman, N.; Cardon, G.; Tallir, I.B.; Haerens, L. Within-person profiles of teachers’ motivation to teach: Associations with need satisfaction at work, need-supportive teaching, and burnout. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teaching Profile | N (Teachers) | N (Students) |

|---|---|---|

| Low structure–low control | 6 | 162 |

| High structure–high control | 11 | 326 |

| High structure–low control | 2 | 52 |

| Students’ Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Autonomous motivation | - | ||||||||||

| 2 Controlled motivation | 0.483 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3 Amotivation | −0.234 ** | 0.142 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4 Autonomy satisfaction 5 Competence satisfaction | 0.647 ** | 0.418 ** | −0.099 * | - | |||||||

| 0.528 ** | 0.238 ** | −0.136 ** | 0.567 ** | - | |||||||

| 6 Relatedness satisfaction | 0.540 ** | 0.356 ** | −0.154 ** | 0.663 ** | 0.473 ** | - | |||||

| 7 Autonomy frustration | −0.320 ** | 0.144 ** | 0.469 ** | −0.269 ** | −0.269 ** | −0.246 ** | - | ||||

| 8 Competence frustration | −0.166 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.350 ** | −0.131 ** | −0.313 ** | −0.148 ** | 0.598 ** | - | |||

| 9 Relatedness frustration | −0.038 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.308 ** | −0.015 | −0.165 ** | −0.156 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.570 ** | - | ||

| 10 Behavioral engagement | 0.383 ** | 0.332 ** | −0.124 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.243 ** | 0.336 ** | −0.124 ** | −0.023 | 0.005 | - | |

| 11 Agentic engagement | 0.474 ** | 0.321 ** | −0.067 | 0.510 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.433 ** | −0.172 ** | −0.152 ** | −0.033 | 0.476 ** | - |

| M | 3.75 | 3.33 | 2.11 | 3.19 | 3.70 | 3.58 | 2.50 | 2.36 | 2.23 | 3.94 | 3.40 |

| SD | 0.85 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 0.95 |

| Teachers’ variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 1 Profile structure | - | ||||||||||

| 2 Guiding | 0.882 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3 Clarifying | 0.879 ** | 0.550 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4 Profile control | 0.418 ** | 0.207 | 0.531 ** | - | |||||||

| 5 Demanding | 0.464 ** | 0.301 * | 0.518 ** | 0.921 ** | - | ||||||

| 6 Domineering | 0.327 * | 0.101 | 0.476 ** | 0.944 ** | 0.741 ** | - | |||||

| 7 Autonomy support | 0.318 * | 0.334 * | 0.225 | −0.014 | 0.076 | −0.089 | - | ||||

| 8 Competence support | 0.495 ** | 0.512 ** | 0.358 ** | −0.014 | 0.122 | −0.128 | 0.795 ** | - | |||

| 9 Relatedness support | −0.201 | −0.231 | −0.123 | 0.052 | −0.019 | 0.106 | −0.154 | −0.174 | - | ||

| M | 5.42 | 5.84 | 5.01 | 3.36 | 3.82 | 2.90 | 6.28 | 6.21 | 1.37 | ||

| SD | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.17 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.81 |

| Teachers | Low Structure–Low Control (n = 6) | High Structure–High Control (n = 11) | High Structure–Low Control (n = 2) | F (df) | η2 Partial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | 4.41 (0.90) a | 6.04 (0.24) b | 5.83 (0.00) b | 18,18 (2) *** | 0.694 |

| Guiding | 4.93 (1.04) a | 6.34 (0.33) b | 5.86 (0.00) | 9.48 (2) ** | 0.542 |

| Clarifying | 3.90 (0.79) a | 5.75 (0.53) b | 5.80 (0.00) b | 19.11 (2) *** | 0.705 |

| Control | 2.14 (0.32) a | 4.61 (0.60) b | 2.65 (0.11) a | 50.22 (2) *** | 0.863 |

| Demanding | 2.33 (0.48) a | 4.89 (0.61) b | 3.00 (0.20) a | 43.49 (2) *** | 0.845 |

| Domineering | 1.97 (0.48) a | 4.33 (0.85) b | 2.30 (0.42) a | 22.62 (2) *** | 0.739 |

| Students | Low Structure–Low Control (n = 162) | High Structure–High Control (n = 326) | High Structure–Low Control (n = 52) | F (df) | η2 Partial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous motivation | 3.74 (0.91) | 3.70 (0.83) b | 4.06 (0.78) a | 3.98 (2) * | 0.015 |

| Controlled motivation | 3.27 (0.66) b | 3.31 (0.64) b | 3.58 (0.72) a | 4.54 (2) * | 0.017 |

| Amotivation | 2.05 (1.12) | 2.18 (1.05) a | 1.76 (0.93) b | 3.86 (2) * | 0.014 |

| BPN satisfaction | 3.40 (0.86) b | 3.48 (0.79) b | 3.81 (0.70) a | 5.19 (2) *** | 0.019 |

| Autonomy satisfaction | 3.06 (0.98) b | 3.17 (0.92) b | 3.67 (0.85) a | 8.62 (2) ** | 0.031 |

| Competence satisfaction | 3.74 (0.99) | 3.63 (0.95) | 3.94 (0.85) | 2.51 (2) | 0.009 |

| Relatedness satisfaction | 3.40 (1.03) b | 3.63 (0.96) a | 3.82 (0.94) a | 4.80 (2) ** | 0.018 |

| BPN frustration | 2.30 (0.90) a | 2.44 (0.83) a | 2.04 (0.86) b | 5.43 (2) ** | 0.020 |

| Autonomy frustration | 2.49 (1.12) | 2.55 (1.04) a | 2.14 (1.09) b | 3.28 (2) * | 0.012 |

| Competence frustration | 2.29 (1.06) | 2.44 (0.99) a | 2.00 (0.96) b | 4.84 (2) ** | 0.018 |

| Relatedness frustration | 2.11 (1.08) | 2.33 (1.02) | 1.99 (0.90) | 4.13 (2) * | 0.015 |

| Engagement | 3.74 (0.69) b | 3.58 (0.73) b | 3.98 (0.73) a | 7.79 (2) ** | 0.028 |

| Behavioral engagement | 3.96 (0.67) b | 3.87 (0.77) b | 4.33 (0.63) a | 9.16 (2) *** | 0.033 |

| Agentic engagement | 3.51 (0.96) | 3.30 (0.92) | 3.62 (1.08) | 4.41 (2) * | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coterón, J.; Fernández-Caballero, J.; Martín-Hoz, L.; Franco, E. The Interplay of Structuring and Controlling Teaching Styles in Physical Education and Its Impact on Students’ Motivation and Engagement. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090836

Coterón J, Fernández-Caballero J, Martín-Hoz L, Franco E. The Interplay of Structuring and Controlling Teaching Styles in Physical Education and Its Impact on Students’ Motivation and Engagement. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090836

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoterón, Javier, José Fernández-Caballero, Laura Martín-Hoz, and Evelia Franco. 2024. "The Interplay of Structuring and Controlling Teaching Styles in Physical Education and Its Impact on Students’ Motivation and Engagement" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090836

APA StyleCoterón, J., Fernández-Caballero, J., Martín-Hoz, L., & Franco, E. (2024). The Interplay of Structuring and Controlling Teaching Styles in Physical Education and Its Impact on Students’ Motivation and Engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090836